Walker Evans was an American photographer best known for documenting the effects of the Great Depression for the

Farm Security Administration (FSA). The large-format, 8x10-inch camera was used extensively by Evans during the FSA period. As a photographer, he aspired to create images that are

"literate, authoritative, transcendent". Many of his works are in museum permanent collections, and he has had retrospectives at places like the

Metropolitan Museum of Art or

George Eastman House.

Walker Evans was born into a wealthy family in St. Louis, Missouri, to Jessie (née Crane) and Walker. His father worked as an ad executive. He grew up in Toledo, Chicago, and New York City. In 1922, he graduated from Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts. He attended Williams College for a year, studying French literature and spending most of his time in the library, before dropping out.

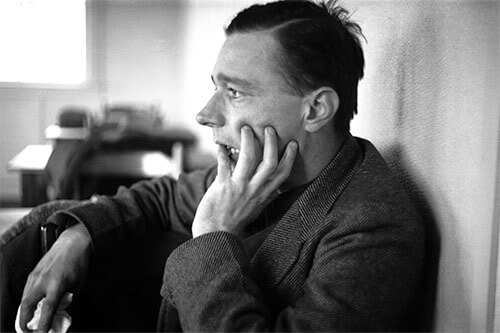

In 1926, he returned to the United States to join the edgy literary and art crowd in New York City after spending a year in Paris. Among his friends were

John Cheever,

Hart Crane, and

Lincoln Kirstein. From 1927 to 1929, he worked as a stockbroker's clerk on Wall Street. Evans began photographing in 1928, while living in Ossining, New York. In 1930, he published three photographs (Brooklyn Bridge) in Hart Crane's poetry collection

The Bridge.

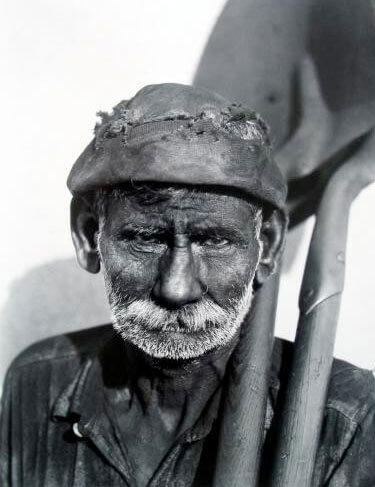

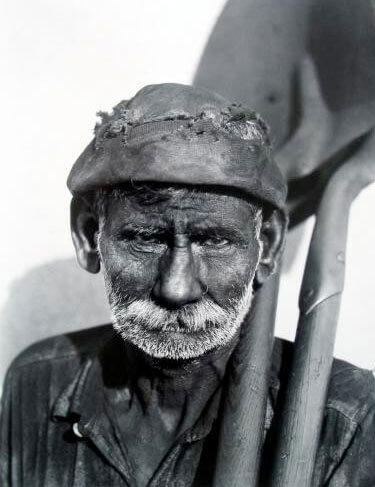

Dock-worker, Havana, Cuba, 1932

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

After spending a year in Paris in 1926,

Walker Evans returned to the United States to join the edgy literary and art crowd in New York City.

John Cheever,

Hart Crane, and

Lincoln Kirstein were among his friends. He was a clerk for a stockbroker firm in Wall street from 1927 to 1929. Evans took up photography in 1928 around the time he was living in Ossining, New York. In 1930, he published three photographs (Brooklyn Bridge) in the poetry book

The Bridge by Hart Crane. Lincoln Kirstein sponsored a photo series of Victorian houses in the Boston area in 1931. In 1933, he photographed the revolt against dictator

Gerardo Machado in Cuba for the publisher of Carleton Beals' then-upcoming book,

The Crime of Cuba. Evans briefly met Ernest Hemingway in Cuba.

With the camera, it’s all or nothing. You either get what you’re after at once, or what you do has to be worthless. -- Walker Evans

Evans began a two-month photographic campaign for the

Resettlement Administration (RA) in West Virginia and Pennsylvania in 1935. From October to December, he continued to photograph for the RA and, later, the

Farm Security Administration (FSA), primarily in the South. While still working for the FSA, he and writer

James Agee were sent on assignment to Hale County, Alabama, by

Fortune magazine for a story that the magazine later decided not to run.

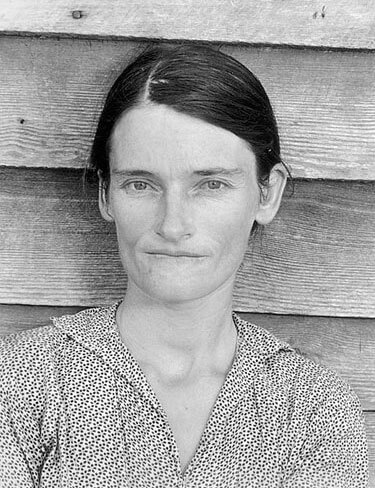

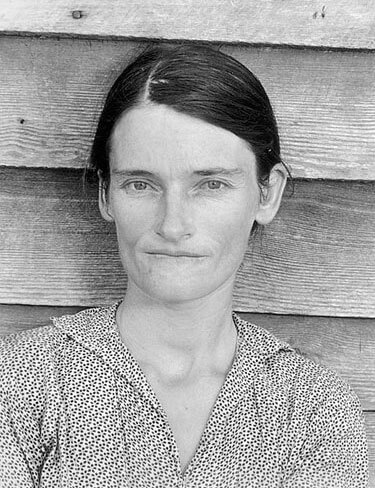

Allie Mae Burroughs, 1935 or 1936

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

, a groundbreaking book published in 1941, featured Evans' photographs and Agee's text detailing the duo's stay with three white tenant families in southern Alabama during the Great Depression. Its detailed account of three farming families paints a heartbreaking picture of rural poverty. In her 1980 book

Diana & Nikon: Essays on the Aesthetic of Photography, critic

Janet Malcolm noted a similarity to the Beals' book, pointing out the contradiction between Agee's prose and the quiet, magisterial beauty of Evans' photographs of sharecroppers. The three families, led by

Bud Fields,

Floyd Burroughs, and

Frank Tingle, lived in the Hale County town of Akron, Alabama, and the landowners told them that Evans and Agee were

"Soviet agents," though

Allie Mae Burroughs, Floyd's wife, later recalled her dismissing that information.

Evans' photographs of the families immortalized their misery and poverty during the Great Depression. For its 75th anniversary issue, Fortune returned to Hale County and the descendants of the three families in September 2005. When Evans and Agee visited the Burroughs family,

Charles Burroughs, who was four years old at the time, was

"still angry" at them for not even sending the family a copy of the book; Floyd Burroughs' son was also reportedly angry because the family was

"cast in a light that they couldn't do any better, that they were doomed, ignorant."

The secret of photography is, the camera takes on the character and personality of the handler. -- Walker Evans

Walker Evans remained with the FSA until 1938. An exhibition,

Walker Evans: American Photographs was on display at

Museum of Modern Art in New York that year. This was the museum's first exhibition devoted solely to the work of a single photographer. The catalogue also included an essay by Lincoln Kirstein, whom Evans had met in his early days in New York. Evans took his first photographs in the New York subway in 1938, with a camera hidden in his coat.

Many are Called was a book that collected these stories in 1966. Evans collaborated with and mentored

Helen Levitt in 1938 and 1939. Evans, like such other photographers as

Henri Cartier-Bresson, rarely spent time in the darkroom creating prints from his own negatives. He only loosely supervised the printing of most of his photographs, sometimes only attaching handwritten notes to negatives with printing instructions.

Evans was an avid reader and writer who joined

Time Magazine's staff in 1945. He then worked as an editor at

Fortune magazine until 1965. That same year, he joined the faculty of the Yale University School of Art as a photography professor. Evans completed a black and white portfolio of Brown Brothers Harriman's offices and partners for publication in

Partners in Banking, which was published in 1968 to commemorate the private bank's 150th anniversary. He also shot a long series with the then-new Polaroid SX-70 camera in 1973 and 1974, after age and poor health made it difficult for him to work with elaborate equipment. In 1971, the Museum of Modern Art held another exhibition of his work, simply titled

Walker Evans.

Walker Evans died in 1975 at his home in Lyme, Connecticut. The Estate of Walker Evans donated its holdings to New York City's The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1994. The Metropolitan Museum of Art is the sole owner of all Walker Evans works of art in all media. The only exception is a group of about 1,000 negatives in the

Library of Congress collection that were created for the Resettlement Administration (RA) / Farm Security Administration (FSA). Evans's RA / FSA works are free to use. Evans was inducted into the St. Louis Walk of Fame in 2000.

Images: © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art