Shinji Ichikawa, winner of

AAP Magazine 39: Shadows, was born into a family of photographers in Shimane Prefecture, Japan, where he grew up surrounded by cameras and prints. After graduating from Tokyo Visual Arts, he began his career in commercial photography before moving to New York in 1999 to explore a more personal, surreal approach to image-making. His work often investigates themes of space and presence. Now back in Shimane, he continues to create and exhibit his photography while managing his family’s studio.

We asked him a few questions about his life and work.

All About Photo: Tell us about your first introduction to photography.

Shinji Ichikawa: My very first encounter with photography was as a child peering into my

grandfather’s Mamiya Flex, treating the twin-lens reflex like a toy and marveling

at the miniature world inside the viewfinder.

What started your career as a photographer?

Growing up in a family photo studio, I literally inhaled the chemical scent of the

darkroom, so pursuing photography felt as natural as breathing.

The decisive turning point came in 1998, when I moved alone to New York.

Immersed in the city’s cultural energy and armed with self-directed study, I felt

an irrepressible urge to visualize formless sensations and emotions. Since then

I have built my practice on two pillars: creating artworks as an artist and

working as a craftsman who runs the family studio and applies commercialshoot

skills.

You were born into a family that ran a photo studio. How did growing up

surrounded by cameras and photographs influence your creative instincts?

Witnessing the “magic” of images emerging in chemical baths, waiting with my

father for dawn light and shifting compositions in rural Japan, and silently

observing the timing and precision of portrait lighting in the studio—these three

layered experiences formed a creative stance that prizes tactile quality yet is

bold enough to break it apart in art projects.

Edge of Absence © Shinji Ichikawa

While assisting commercial photographers in Tokyo, I felt my own colors fading.

Seeking answers, I left for New York in 1998, locked my camera away for a year,

and devoted myself to museums, galleries, and books such as The

Photographic Method—an interview collection with 21 photographers. A sudden

insight that those artists were seeing “vibrations in the air” made images flash

before my eyes. The conviction to visualize intangible feelings fused with the

craftsmanship I had honed at home, steering me from commercial assisting to

pure artistic creation.

Your time in New York seems pivotal. How did that period of self-teaching

and exploration shape your approach to photography?

During my first year in New York, I deliberately set the camera aside and

devoted myself to visiting museums and galleries and studying photobooks. By

repeatedly reading the interview collection The Photographic Method, I realized

that the photographers were focusing less on “objects” than on the atmosphere

—the subtle presence drifting through space and time. In that instant I grasped a new approach: building every composition around how to visualize the energy

hidden in the intervals and empty spaces rather than the subject itself. This

shift—observing first, then capturing the faint vibrations of a place—has formed

the core of my work ever since, shaping my current exploration of space and

existence.

You’ve mentioned drawing inspiration from Surrealism. How does that

influence manifest in your current photographic language?

Surrealism emerges in my work as slight dislocations in the seams of reality—

gaps and disquiet that unsettle the viewer’s subconscious.

Themes of “space and presence” often surface in your work. How do you

define those concepts, and why are they central to your vision?

I see “existence” not as a fixed object but as a phenomenon that flickers into

being from moment to moment, while “space” is the stage that allows that

appearance. Therefore I prioritize intervals and blankness over the subject

itself, aiming to reveal both the fragility of ever-shifting existence and the

invisible energy that embraces it.

For me, the root of everything lies in perceiving existence. What seems like

empty space actually contains the elements that let things be. I am drawn to

the silence of nothingness and the impermanence that continually alters form.

Tell us more about your decision to return to Shimane Prefecture in 2001.

How has being rooted there—while managing your family’s photo studio—

shaped the way you see and document the world?

I returned to Shimane in 2001 to oscillate between the “acceleration” etched

into me in New York and the “quiet” of my hometown, layering both sensations

into my work. The city’s torrent of time, metallic fumes, and relentless signage

sharpened my senses and gave me distance to view Japan from the outside.

Conversely, Shimane’s sea breeze, earthy scents, scattered forest light, and the

deep history of Izumo festivals soak in slowly. Commuting between speed and

depth became a lens: my images now fuse urban acuity with local depth. New

York-honed vision settles in Shimane’s tranquil oceans, mountains, and night

sky, reflecting back and revealing overlooked Japanese allure that naturally

reshapes how I record the world.

The Old Man With an Umbrella © Shinji Ichikawa

When my 80-year-old father stood with an umbrella, I sensed aging and death

in his back. I began The Old Man with an Umbrella to visualize the fear of

inevitably losing him and to etch our remaining time together. As the project

evolved, he transcended the personal to become “human” and eventually “a

mere object,” questioning the very boundary between presence and absence.

What role does symbolism play in your storytelling, especially in this

particular series?

By repeating a single black silhouette while altering landscapes, light, and

color, my private model of “father” is elevated into a universal shadow of

existence, prompting viewers to recall their own losses. The closed world

formed by umbrella and silhouette is pierced by sky, clouds, and small hues

that hint at wider time and space; that tension and quiet breath form the core

symbolism of the series.

Pine Trees © Shinji Ichikawa

The Afterglow of Yugen © Shinji Ichikawa

I always begin with intense personal feelings or experiences. I then translate

that origin into visual symbols—color, form, light, blankness—leaving ma

(intervals) so viewers can project their own memories. In this way, personal

warmth and shared abstraction coexist, allowing the narrative to open naturally

onto universal questions of life and death, the passage of time, and presence

versus absence.

Looking at your overall body of work, would you say your style is evolving? If

so, in what direction?

My early work focused on form, texture, and space itself. Gradually my

attention shifted to the “atmosphere” and the “tremor of existence.” Recently I

am drawn to perpetual flux—life and death, being and nothingness.

Incorporating Japanese traditions such as Noh and bonsai, I seek to visualize

these abstractions. The result is a style where quiet forms hold both temporal

flow and psychological depth.

Enso #3 © Shinji Ichikawa

The business and the art feed each other in a cycle. Daily studio shoots let me

experiment with lighting and color management, and those technical

discoveries feed my introspective work. Conversely, the spatial sensibility and

use of blankness from personal projects return to the studio, adding fresh

depth to portraits and product shots. This back-and-forth keeps both craft and

creativity growing.

What future projects are you considering—are there any subjects or concepts

you're eager to explore next?

I plan to translate the “quiet tension” and “condensed time” found in Japanese

traditional arts—Noh choreography and stage ma, the miniature landscapes of

bonsai, the chiaroscuro of classical architecture—into a contemporary

photographic series expressed through my visual language.

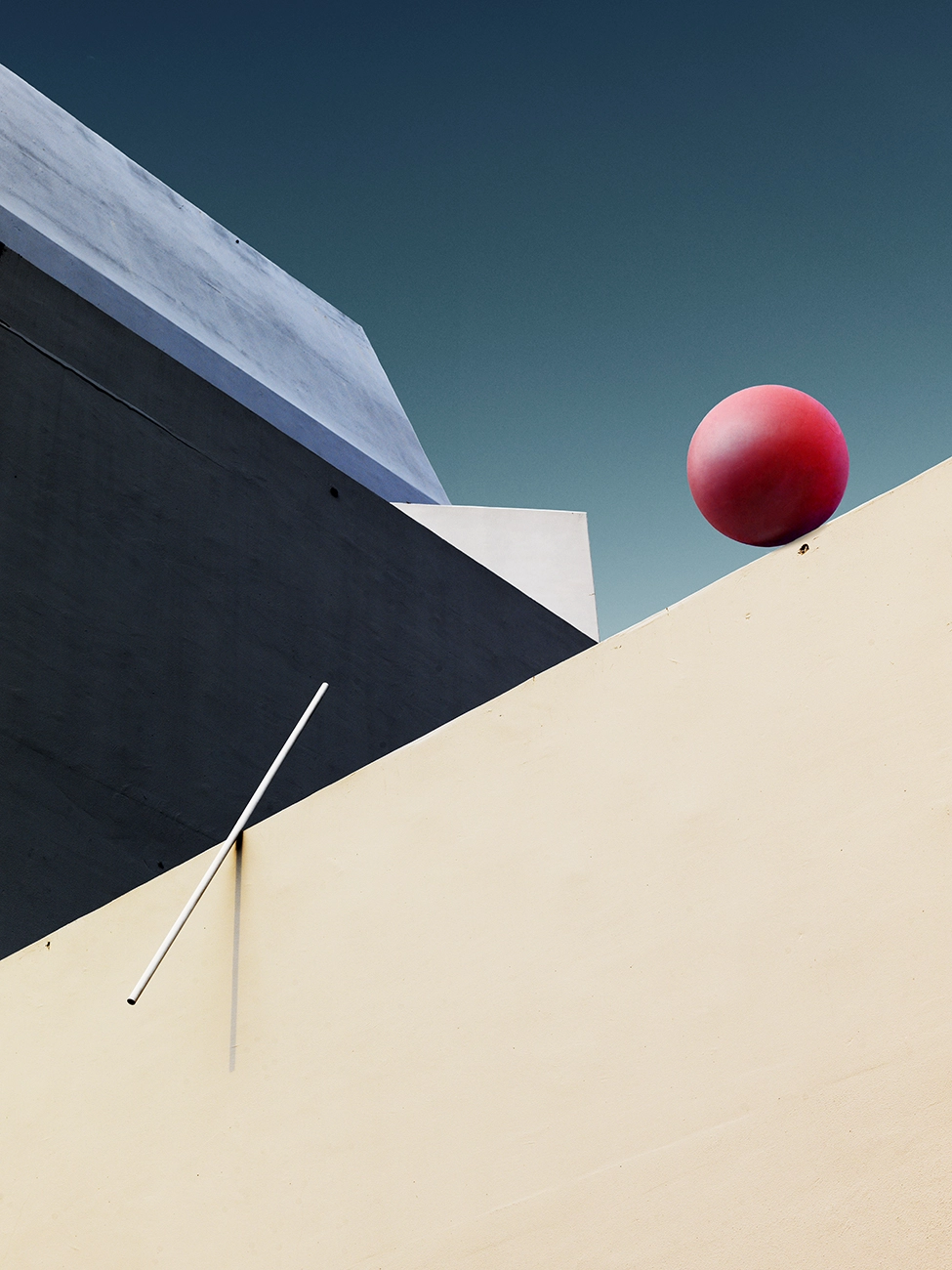

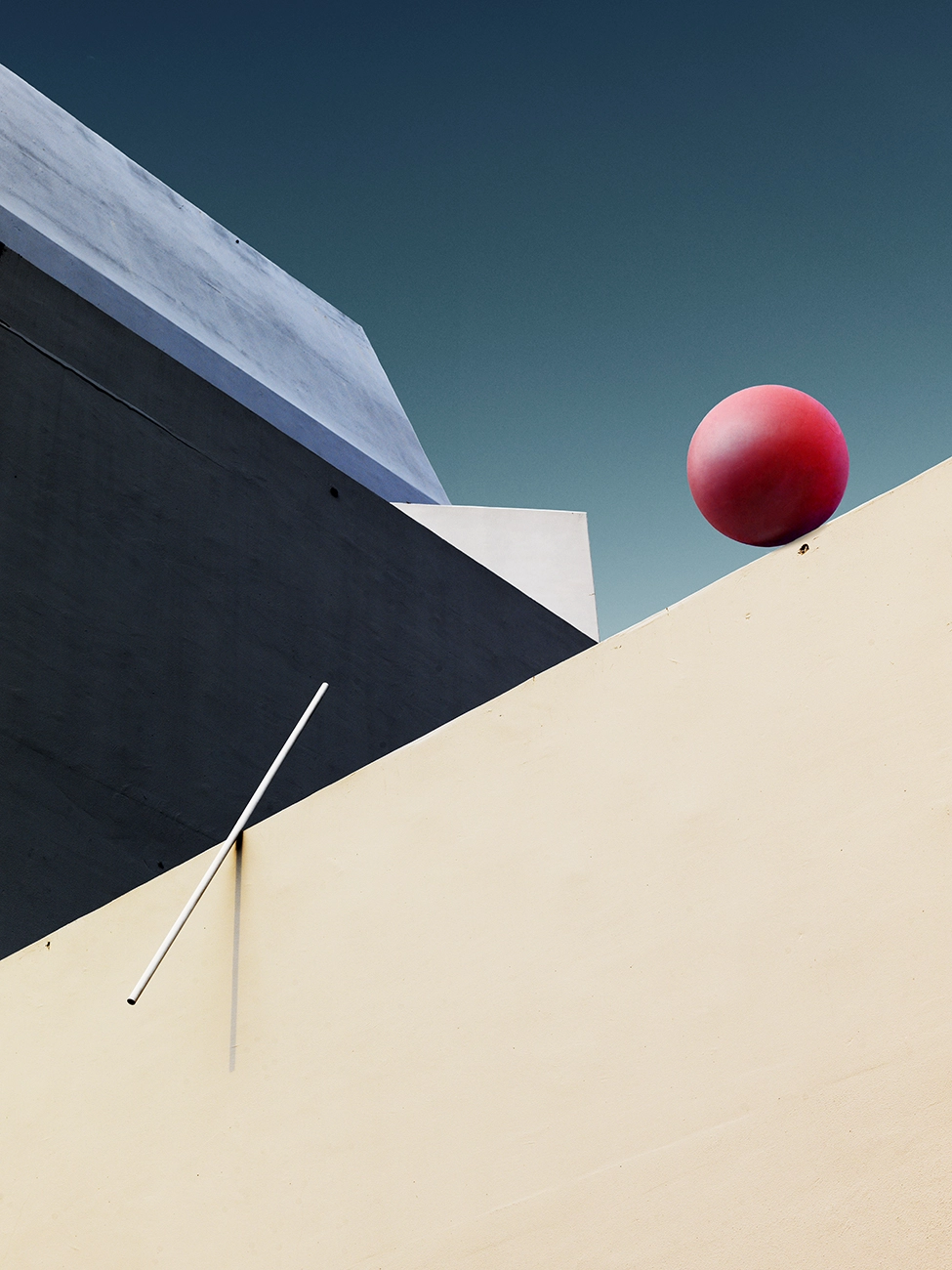

Space One © Shinji Ichikawa

At present, I have no confirmed plans for publishing a photobook or staging a

major solo exhibition. However, in October 2025 I will exhibit in the Sideshow

Exhibition at FotoNostrum Gallery in Barcelona. In addition, my work has been

long-listed for the Aesthetica Art Prize 2025 and will be shown on-screen at

York Art Gallery in the UK from September 2025 through January 2026. I plan

to use these opportunities to gauge the response to my new pieces and to

explore the most suitable format for a future photobook or solo show.

Lastly, what do you hope viewers take away from your photographs—not just

emotionally, but in how they observe the world around them?

I hope viewers experience how a tiny shift—a lengthening shadow, a slight

flicker of light—can transform the entire scene. Once that awareness clicks,

they may pause even in hectic life to observe wind paths, human traces, and

the flow of time. Familiar places reveal new discoveries, and attention and

sensitivity quietly deepen. That small tremor leading to a vast change in

perspective is what my photographs aim to offer.

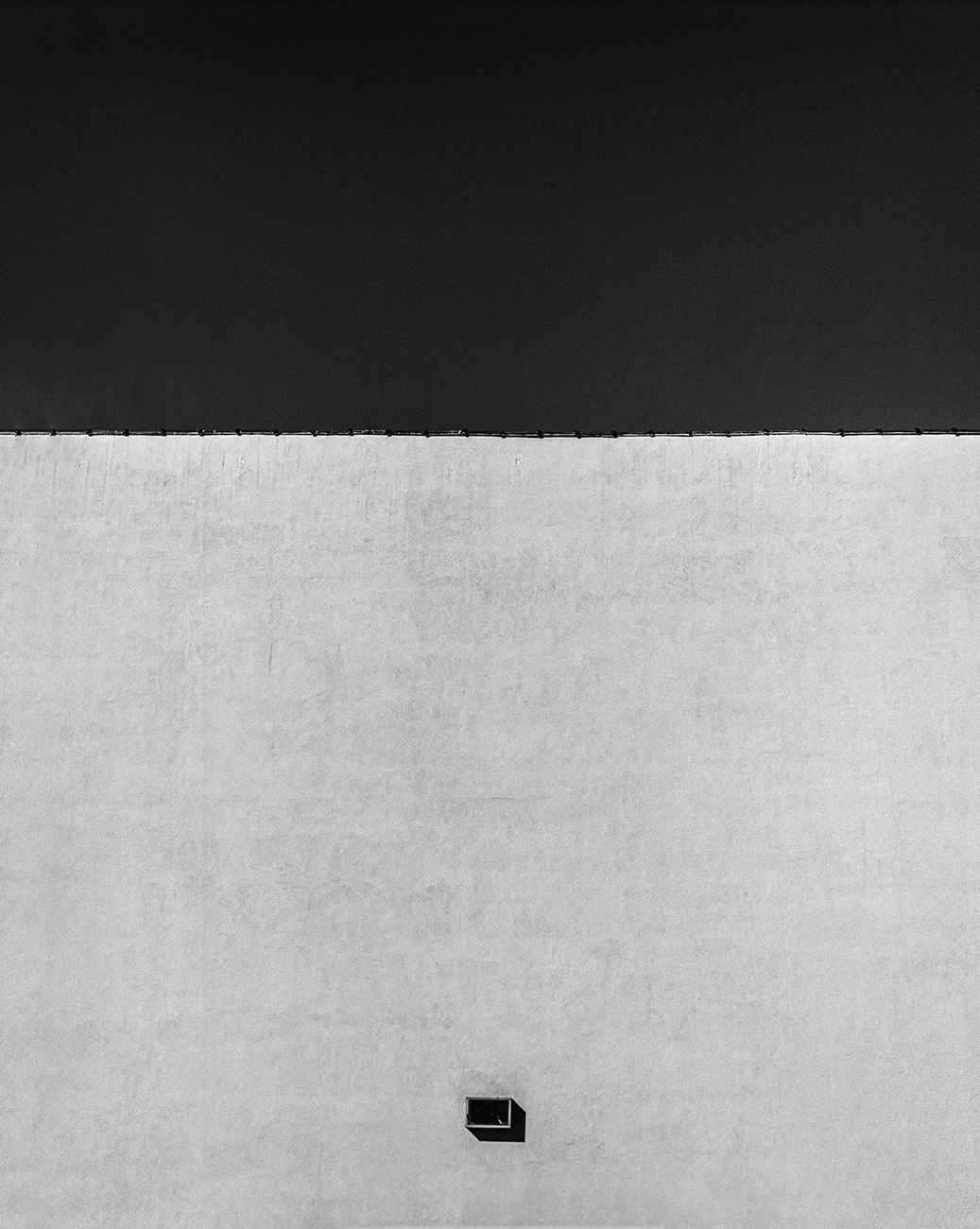

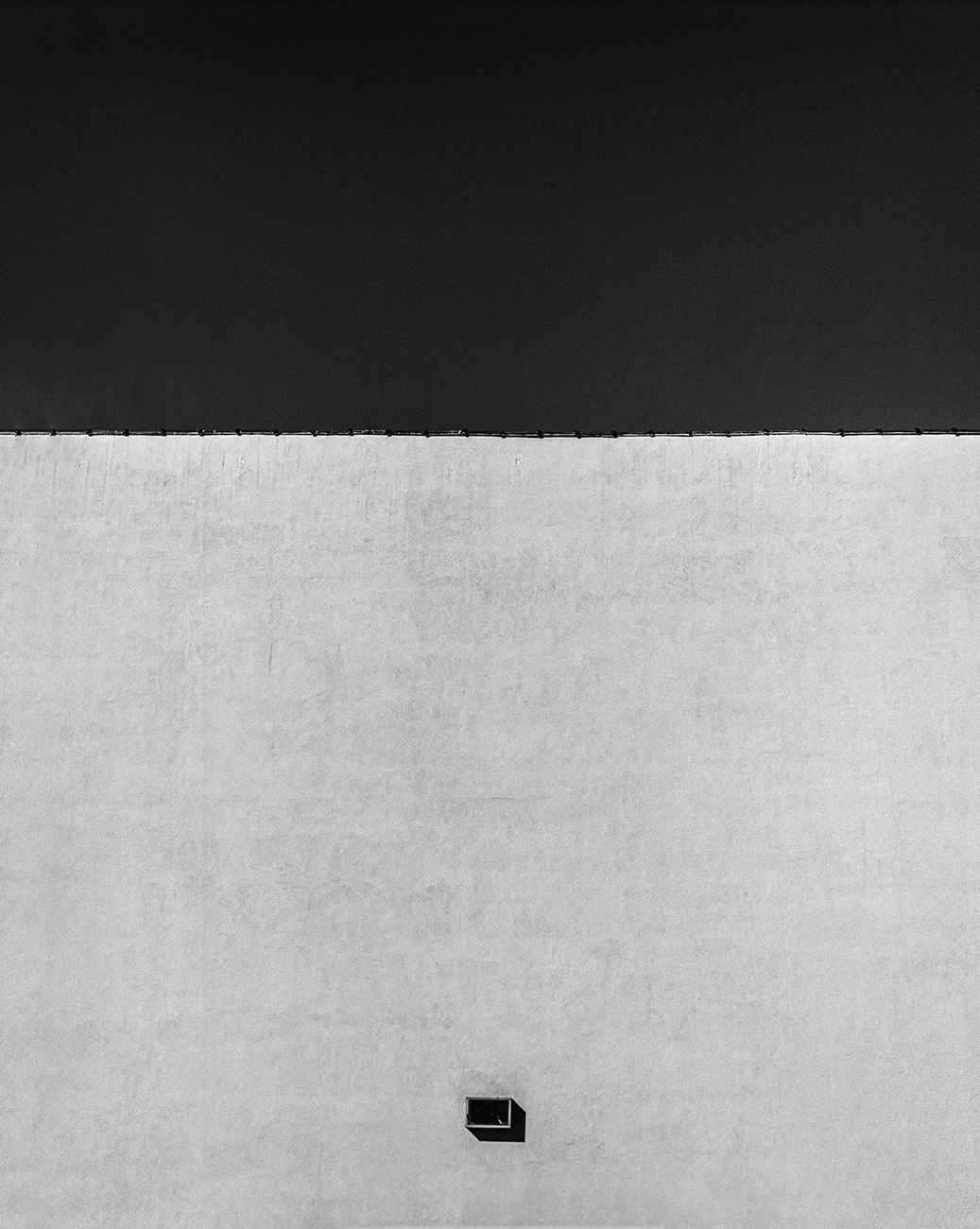

White Wall with Solitary AC © Shinji Ichikawa

Abstract bench © Shinji Ichikawa

Long Island City #2 © Shinji Ichikawa