French photographer

Manuel Besse is known for his compelling black-and-white imagery, which blends portraiture, documentary, and poetic narrative into a singular visual voice. With a career spanning several decades and continents—from the gold mines of Serra Pelada to the Arctic Circle—his work reflects a deep commitment to authenticity, human connection, and the preservation of cultural and natural landscapes.

His series Macadam, winner of

AAP Magazine #41 B&W, offers a contemplative look at fleeting urban encounters, rendered in his signature monochrome style.

We asked him a few questions about his life and work.

All About Photo: Let’s start from the beginning: Can you tell us a bit about your

background? Where did you grow up, and how did your journey into

photography begin?

Manuel Besse: I grew up between two worlds that were polar opposites. Paris, dense, noisy, always in a

hurry; and Corsica, insular, mineral, sculpted by wind and silence. This geographical and

sensory divide taught me very early on to observe, to decode what lies behind appearances.

Then, one evening, everything changed. I was nine years old. In a dark room, a

documentary screened in the first part evoked the Vietnam War. It talked about

Don McCullin. His images were engraved in my mind like shards: lifeless eyes, bruised bodies,

and in the midst of collapse, a dignity that defied death. That day, I understood that a

photograph transcends the very notion of an image. It became a cry, irrevocable proof, a

fragment of humanity torn from the darkness of oblivion.

When I left the cinema, I was a changed person. Shortly afterwards, I borrowed my father's

camera. I still remember the cold body of the camera against my child's hands, the shiver

that ran down my spine as I looked through the viewfinder. Suddenly, I could isolate a face, a

gesture, a light, as if the world were presenting itself to me in a different way. Each time I

pressed the shutter, I felt closer to a truth that I did not yet know how to name.

This need to understand pushed me to go further. After years of self-taught learning, I

pursued a demanding academic career by enrolling at the Louis-Lumière school, where I

trained in photography and cinema, before completing a PhD in ethnology at Paris Cité

University. At the same time, I deepened my knowledge of the visual arts by studying fine

arts at the École du Louvre and the Académie Charpentier. But deep down, I already knew

that my real school would not be within four walls; it would be outside, in the streets, on the

roads, in the jungle, in the heart of those places where no one goes and yet where

everything happens. Where humanity reveals itself, raw, indomitable, with an incredible

intensity that only photography can truly convey.

© Besse Manuel, Agence Posto 5, 2023

Black and white... It's as if the world falls silent to better reveal itself. It all begins with

silence. Colors fade away, and suddenly light becomes palpable, almost sharp, like a blade

sculpting the contours of reality. Faces have no escape. Every wrinkle becomes a

landscape, every sparkle in the eye a confession, a sign of life. I have always been

fascinated by the way black and white strips people and places bare, forgiving them nothing.

I can still see my teenage bedroom, the door closed, leaning over the books of Don McCullin

and James Nachtwey. I turned their pages as one would handle relics. Their black and white

images hit me hard; the terrified face of a Cambodian child, the dust-covered ruins of Beirut,

the ghostly silhouettes of Vietnamese soldiers crossing a mud-covered landscape... They did

not seek to seduce. They burned. And in that burning, I perceived something universal: pain,

dignity, human fragility.

Since then, I have never strayed from this approach. Black and white strips away the

superfluous. It suspends time. It expands the image beyond the moment it captures. When I

photograph in these shades, I am not trying to “make it pretty.” I seek to feel. To reveal. It is a

language that can express the inexpressible. The loneliness of an old man under a bus

shelter, the vertigo of a deserted street at dawn, the strength of a gaze that defies adversity.

It's not just aesthetics. It's a way of laying bare the truth of people and places, of going

straight to the heart. When I photograph in black and white, I pursue the truth, raw and

unadorned. Because it is often in the absence of color that humanity strikes me the hardest.

You’ve mentioned Don McCullin’s Vietnam War documentary as an

early influence. How did that experience shape your vision as a

photographer?

I was nine years old. The movie theater was plunged into darkness, with that smell of dust

and velvet that clings to old theaters. The silence was thick, almost tangible. Then the

screen lit up and everything changed; the documentary on the Vietnam War, Don McCullin's

images. Those faces marked by fear, those bodies collapsed in the mud, that sharp light on

the shadows... It was brutal. I felt my stomach knot, my throat tighten. I had never seen

anything so raw and so real at the same time.

I remember looking away for a split second, unable to bear certain images. But I looked back

immediately, as if a stronger instinct was telling me to face the truth. There, amid the chaos,

were gestures of overwhelming humanity. A soldier carrying his wounded comrade, a mother

clutching her terrified child. These glimpses of life pierced me. I understood that photography

could be both a protest and a refuge, a means of bearing witness to horror, but also of

saving what deserves to be saved.

These images haunted me for a long time. Without necessarily appealing to me, they

showed the world as it is, without embellishment, and reminded me that there is a red line

that must never be crossed: looking away. I understood, that day, that photography could be

an act of truth, a gesture that matters. That it could convey inhumanity, but also preserve

fragments of humanity amid the chaos.

Since then, every time I raise my camera to my eye, I remember that feeling. Each time I

press the shutter, something is at stake: memory, dignity, the refusal to forget. Don McCullin

taught me that; the need to photograph without looking away, with all the weight and

responsibility that entails. It is this requirement that still guides my photography today.

© Besse Manuel, Agence Posto 5, 2024

I choose places where the world cracks open and reveals itself. The United States, Eurasia,

Rio, the Arctic—these are not pins on a map, but fault lines where you can feel the pressure

of time and lives colliding. I go there for the harsh, low-angled, unforgiving light, but above all

for what it reveals: the dignity that persists in adversity, the invisible that stubbornly endures.

I am interested in margins, thresholds, areas where one world passes into another. An

avenue that tips over into the suburbs, a social border in the city center, an isolated

community battered by the polar wind. There, reality is more expressive.

Each territory unsettles me, and that is precisely what I am looking for. I remember, for

example, that mining town in Eurasia where the inhabitants had not seen a stranger in

months. The air smelled of coal and iron, and the streets seemed timeless. Or that Arctic

village where an old hunter taught me to read the cracks in the ice like a book. These

encounters shape my perspective. They force me to listen first, to understand the codes

before translating the world into images.

Photographing a place or culture that I am unfamiliar with begins with learning to be silent. I

read, I map, I meet the locals before pressing the shutter button. Once there, I walk for a

long time, without my camera in hand for the first few hours, sometimes the first few days. I

listen to the voices, the lulls, the rhythm of a neighborhood. I work lightly, at eye level,

without intrusive devices. I rely on intermediaries: a lookout, a community leader, a local

association. I explain my framework, my intentions, and what I will do with the images.

Consent is not a formality; it is the condition for shared truth. And I give back prints, news, a

presence that often goes beyond the actual shooting.

My ethics can be summed up in five verbs: observe, feel, respect, respond, and restore.

Observe without exoticizing: avoid the easy spectacle, prefer nuance, the fatigue of a gaze,

the way the light falls on a hand. Feel: be open to the emotion of the place, to the fragility of

an encounter. Respect: preserve the dignity of those I encounter and protect those who

might be exposed. Respond to my choices: take responsibility for what I show and what I

leave unsaid. Finally, restore: place the images in a narrative that does not confiscate

speech, but relays it.

At every latitude, black and white helps me strip away the scenery and keep only the

essential: human presence. The place is a theater of forces; my job is to reveal its gravity

without betraying those who inhabit it.

© Besse Manuel, Agence Posto 5, 2023

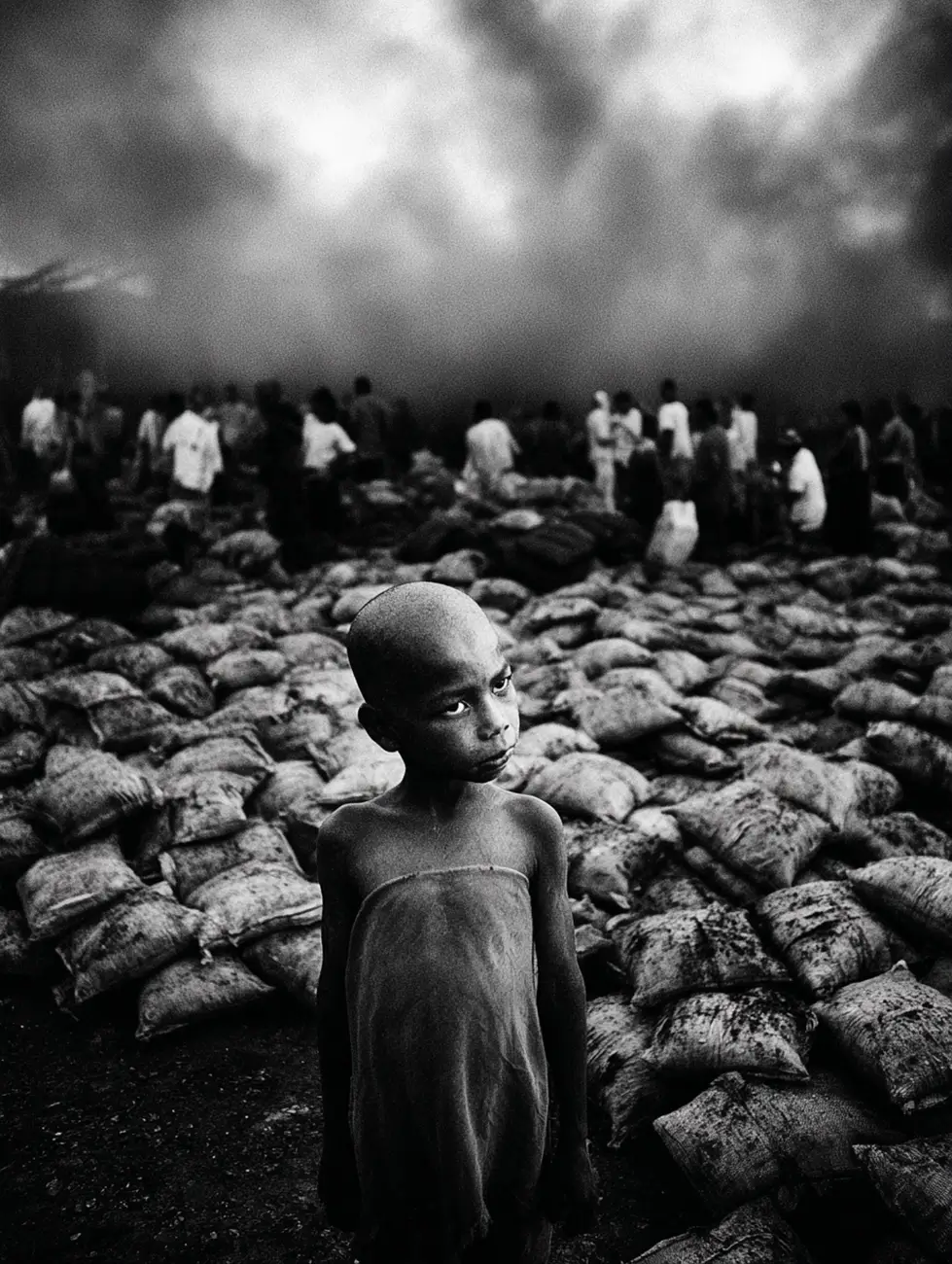

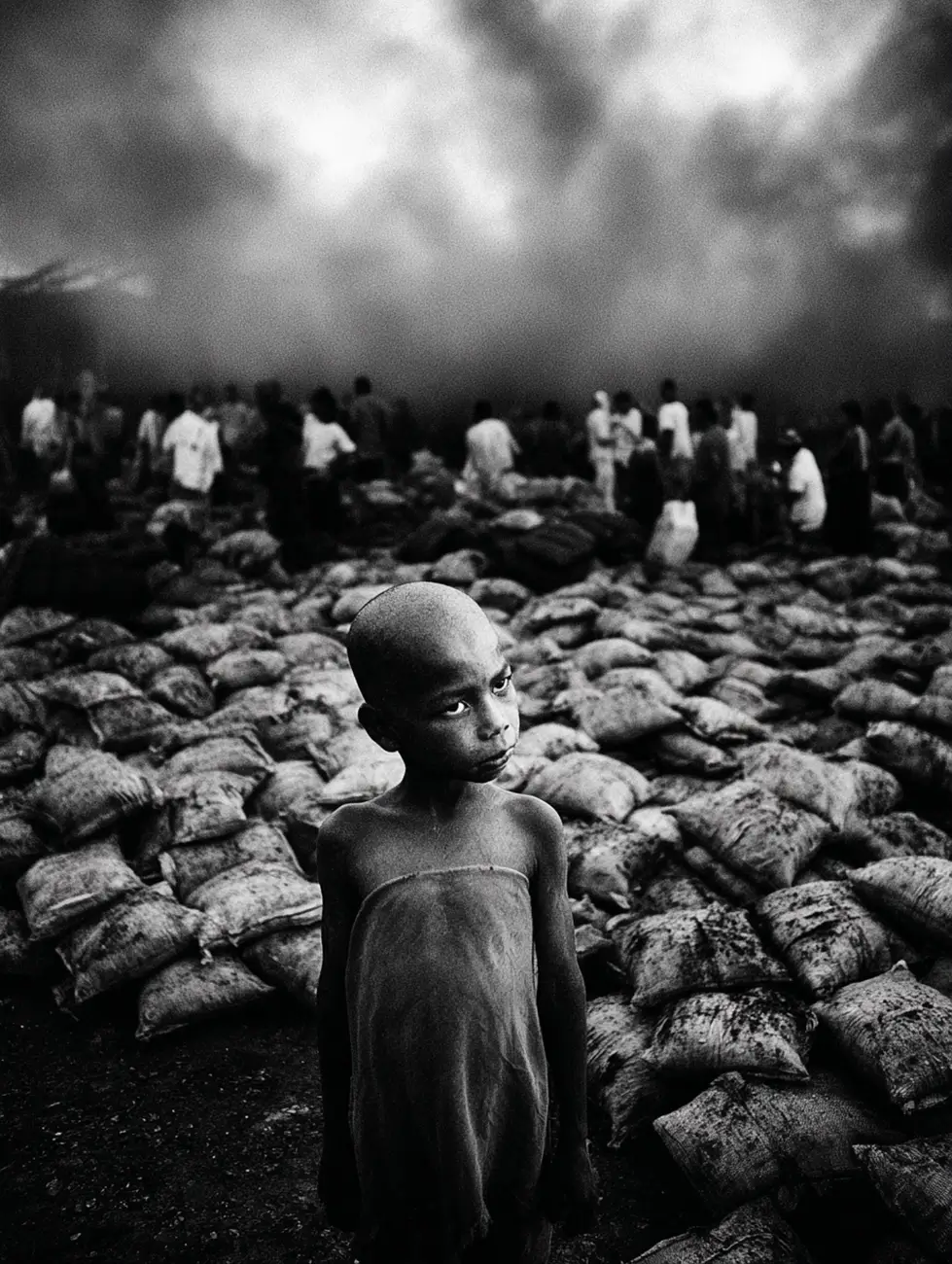

I was 23 when I discovered Serra Pelada. It wasn't a place, it was an open wound. A human

rush, almost unreal, where the earth opened up under the feet of thousands of men, walking

in single file, their bodies dripping with mud, bags of ore rising and falling like an organic

breath. The air was heavy, saturated with humidity, iron, fear. The mud stuck to our knees,

and by the end of the day, we had it all over our bodies. Screams pierced the din, and

everywhere, there was that metallic smell of wet earth that I have never forgotten.

At the time, I didn't know that

Sebastião Salgado had already been there before me. The

internet didn't exist, images didn't circulate as they do today. I discovered everything for

myself, without reference, without comparison, guided only by the need to see and bear

witness.

Getting there was no easy task. It took days of driving, a lot of walking, long negotiations

with the group leaders, the garimpeiros, and clear promises about what I would and would

not do with the images. I worked lightly, at eye level, the camera pressed against my chest

so it wouldn't slip. Every step was tense. The light was harsh, with no shelter or escape.

Dust seeped in everywhere, even into the film. Every shot had to count. It wasn't about

stealing images, but about inhabiting a moment, taking responsibility for it.

What I learned in Serra Pelada still stays with me. First, gravity: photographing weight—that

of bodies, of the ground, of the system—without ever giving in to the temptation of spectacle.

Then, responsibility: naming, explaining, asking, and knowing how to refuse an image if it

exposes. There, I understood that reporting is not an act of capture, but an act of exchange;

I was entering into a relationship. Black and white imposed itself as the obvious choice,

because it removed the backdrop to reveal the substance, the sweat, the dignity. I also took

some color pictures.

I also learned about the choreography of crowds; that repetitive, almost sacred movement,

where every gesture becomes ritual. And between two gestures, silence. A void often more

eloquent than a cry. Blending into the background as a young European photographer with

light eyes was not easy. There is mistrust. Even misunderstanding.

Years later, I discovered Salgado's work in Serra Pelada. And I understood something

fundamental: he had a societal, global approach, whereas mine was above all social, closer

to individuals. He questioned the great movements of the world; I focused on faces, on

individual stories. This difference was not a difference in values, it was my focus, my way of

existing as a photographer.

This experience shaped all my future projects. It led me to places of division, to marginalized

neighborhoods in the United States, to the favelas of Rio, and even to the Arctic Circle.

Everywhere, I used the same method: walking for a long time before taking photographs,

listening, working with guides, writing down first names, and restoring.

Everywhere, the same requirement: not to exoticize, not to snatch an image, but to earn it.

Serra Pelada, a gold mine that has now become a stagnant lake, surrounded by eroded

embankments and sparse vegetation, taught me to see verticality in the dust, human

persistence in the violence of the world, to look at dignity in effort, and to inscribe my images

in a narrative that responds to those it shows. One does not look with impunity. One does

not bear witness lightly. At 23, I found my focus: to go where the earth is hollowed out and

where humans persist, alive and well, surviving.

© Besse Manuel, Agence Posto 5, Beija Flor, 2025

In my opinion, there is no clear boundary between documentary instinct and artistic

expression. The two feed off each other, question each other, and elevate each other. I need

the rigors of documentary to remain grounded in reality, in the raw truth of a scene with its

unspoken words, its tensions, its blind spots. But I also need artistic inspiration to go beyond

simple observation, to experience what lies beneath appearances, what is unspoken but felt.

When I press the shutter, I never ask myself whether I am a storyteller or an artist. I stand on

a knife edge, faithful to the world I photograph, but searching for a form that conveys its

invisible emotional charge. Documentary photography imposes a rigorous, ethical, and

responsible framework on me. Art gives me the freedom to explore the contrasts, the

breathing, the rhythm of an image. It is not a question of embellishing it, but of taking it to

another level of legibility, almost universal.

Because an image, if it merely shows, often ends up becoming exhausted. What drives me

to photograph is the thrill it can provoke when it touches something intimate in the viewer. A

successful image does not freeze. It questions. It leaves room for doubt. It opens up a path

for reflection. It becomes a pretext for exchange. In this sense, I believe that the

photographer is both a witness who tells a story and an artist who sculpts light so that reality

sometimes transcends itself.

For me, photography is an art of tension, between fidelity and interpretation, between raw

presence and shaping. It is an unstable balance. A constant movement. And it is in this

imbalance that my most accurate images are born.

You’ve studied at prestigious institutions like the École Louis-Lumière

and the École du Louvre. How has your formal education influenced your

work in the field?

These schools gave me a solid foundation and memories that are deeply ingrained. At

Louis-Lumière, I can still see the dark rooms where we developed our films, the acrid smell

of chemicals that stuck to our fingers, the almost military precision of the lighting classes. We

were trained to be rigorous: to understand every light source, every shadow, every aperture.

We had to be technically flawless, almost invisible behind our equipment.

At the École du Louvre, I discovered another dimension: art history, the great masters, the

weight of images over time. Understanding how a work of art travels through the centuries

helped me to think of my photographs as fragments that are part of something larger than

myself.

But I quickly realized that degrees alone would not be enough. The street, travel, and

encounters became my real school. In the field, there are no second chances. The light

changes, people look away, a gesture disappears if you don't know how to read it.

What these institutions gave me was a solid foundation; what my field experience gave me

was instinct. This dual training, academic and empirical, taught me that technique is a

foundation, but it is only valuable if you know how to go beyond it. Today, I believe that my

work thrives on this balance between the construction learned in schools and the

deconstruction necessary to rediscover the truth of a moment. It is this ongoing dialogue that

nourishes my images.

© Besse Manuel, Agence Posto 5, 2024

My photographic process begins well before the first shot is taken. I walk, I observe, I make

myself available. Before taking out my camera, I take the time to get a feel for a place.

Totally immersed in my surroundings, I sometimes go days without taking a single picture.

This is my way of understanding the rhythm of a space, the way the light falls and changes

throughout the day, the silences that say more than words.

I use both digital and film, depending on my intention. Digital—full-frame Sony

cameras—allows me to be responsive in fast-moving environments: demonstrations,

crowds, unstable areas. But when I want to slow down and weigh each shot, I choose film. I

often use a Leica 35 mm for its discretion, but also a Hasselblad C 500 equipped with an 85

mm lens.

Medium format changes everything: the pace, the breath, the attention. Every shot counts.

The weight of the camera, the sound of the shutter, the wait for the film to be developed...

everything becomes more intense. For me, the format is not a technical detail. It directly

influences my posture. The 35 mm allows me to immerse myself, at eye level; the medium

format, more sedate, leads me to frame with a different tempo, to seek accuracy in

slowness.

I finally understood that the choice of tool influences the image as much as the light or the

subject. The equipment is not an end in itself. It is a way of positioning oneself in relation to

reality. Digital technology offers the necessary flexibility in contexts where everything can

change from one moment to the next. I switch between the two because each one gives me

a different perspective. Each device induces a different relationship with the world. One

plunges into the flow, the other sculpts time. Film forces me to concentrate completely;

digital forces me to rely on instinct. And I believe that my images are the result of this

balance.

Do you have a particular workflow for editing your black-and-white

images? What tools or techniques do you use to achieve the atmosphere and

tones in your photos?

I edit my black-and-white images as if I were developing a silver print in a darkroom, slowly,

respectfully, and with concentration. It's never about transforming, but about revealing. What

I seek to recreate is what I felt at the moment the photo was taken, the light, the atmosphere,

not to embellish or betray.

My work is based on subtle adjustments, density, contrast, depth of blacks, and vibration of

grays. I use Lightroom and Photoshop, with an approach inspired by film photography. Each

correction is measured, almost physical. I can spend hours on a single image, as if sculpting

the light until it finds its natural balance.

My goal always remains the same: for the technique to fade into the background. I want the

viewer to forget the processing and be drawn into what the image is saying. Too much black,

too much contrast can betray the subject. It is necessary to find that subtle balance that

preserves the truth while revealing the inner strength of the image. In short, I retouch little,

but I retouch well. Lighten what needs to be lightened, darken what can be darkened, and let

the nuances speak for themselves.

© Besse Manuel, Agence Posto 5, USA Détroit Michigan 2024

Trust doesn't just fall from the sky. It is built patiently. And often, it takes time. When I work

on series like Macadam, I spend days, sometimes weeks, blending into the environment. I

walk, I observe, I sit among those I want to photograph. I accept to remain invisible, to

trigger nothing. In these streets, in these margins where mistrust is second nature, the

slightest misstep can close all doors.

I don't hide. I go out and meet people. I explain why I'm there, what I'm trying to do, and

above all what I won't do. I show prints from my previous projects. It's not a gimmick. It's

proof. Proof that I'm not coming empty-handed, that I'm not a tourist hungry for thrills. I also

say that I'd rather leave empty-handed than capture an image that wasn't given to me.

People can sense right away whether you're genuine or not.

For Macadam, I sometimes spent several days with certain people before even taking out

my camera. We shared a coffee in a dented cup, a dusty bench, a silence. These moments

are just as important as the shots. Sometimes all it takes is a gesture to create a bond. A

handshake, an invitation to stay. And then I know I can begin. When I finally press the

shutter, the dialogue is already underway.

The gaze does not stray; it is fixed on the lens. It is this shift that I am looking for. The

moment when the other person ceases to be a subject and becomes a counterpart. It is not

a matter of technique. It is a posture, a promise. And you have to be prepared to keep that

promise. To come back, explain, show, sometimes even protect. Macadam's portraits are not

stolen. They are sequences of encounters. They bear the fatigue of the street, but also the

dignity of those who stand tall despite everything.

I have seen looks that say they have nothing left, others that defy, and still others that hope

we will finally see them as they are. It's hard. But that's where I find humanity. In this

face-to-face encounter, without masks, without escape. Photographing these communities

means accepting to be shaken up, to sometimes feel out of place. But it also means

understanding that no accurate image can be created without this foundation of trust and

respect. And that is something I defend to the end.

Do you consider your photography more documentary or fine art—or

is the line deliberately blurred?

I come from documentary photography, but I refuse to limit myself to it. My starting point is

always reality, the streets, the margins, forgotten communities. Nothing is staged. But I can't

just observe. What drives me to photograph is the conviction that even in chaos, there is a

form of beauty to be revealed. Not decorative beauty. A beauty that emerges from the

shadows, from the asphalt, from a resistant gaze.

My Macadam and Nod series are deeply documentary in nature: I live with those I

photograph, I immerse myself, I share their feelings. But I construct each image as a painter

works on his canvas. I often think of William Turner. I admire his way of transforming light

into living matter, of letting forms dissolve into an almost sacred atmosphere. In my images, I

seek something similar: that vibration where reality ceases to be purely factual and becomes

timeless.

I remember one morning in Rio, the city still slumbering. Mist rose from the hills like a veil,

engulfing the buildings. A silhouette appeared on the sidewalk, barely outlined by the gray

light of dawn. The scene reminded me of Turner. Everything seemed ready to dissolve, and

yet the humanity of that standing body resisted, like the stacks, pillars of the sea, resist the

retreat of the coastline. I experienced the same feeling in the Amazon while watching a

fisherman, alone in his canoe at sunrise, surrounded by a golden mist where the water and

sky merged. These moments are rare. They require patience and a visceral attention to the

world.

Documentary gives me grounding; not to betray, not to invent. But art gives me

the opportunity to show the beauty that remains, even in adversity. In Nod, a child from the

favelas bathed in oblique light sometimes takes on the appearance of Caravaggio; in

Macadam, a face lost in the fog is imbued with the nitescence of a Turner. These

correspondences are not calculated. They arise when we agree to look at the world with that

intensity.

I deeply believe that the role of the photographer is not limited to bearing witness, but also

consists in reminding us that, even in its fractures, humanity carries within it something

indestructible. One must be a witness, but look like a painter. It is in this tension that my

images live. They document reality, while opening a window onto a part of beauty that time

sometimes makes us forget.

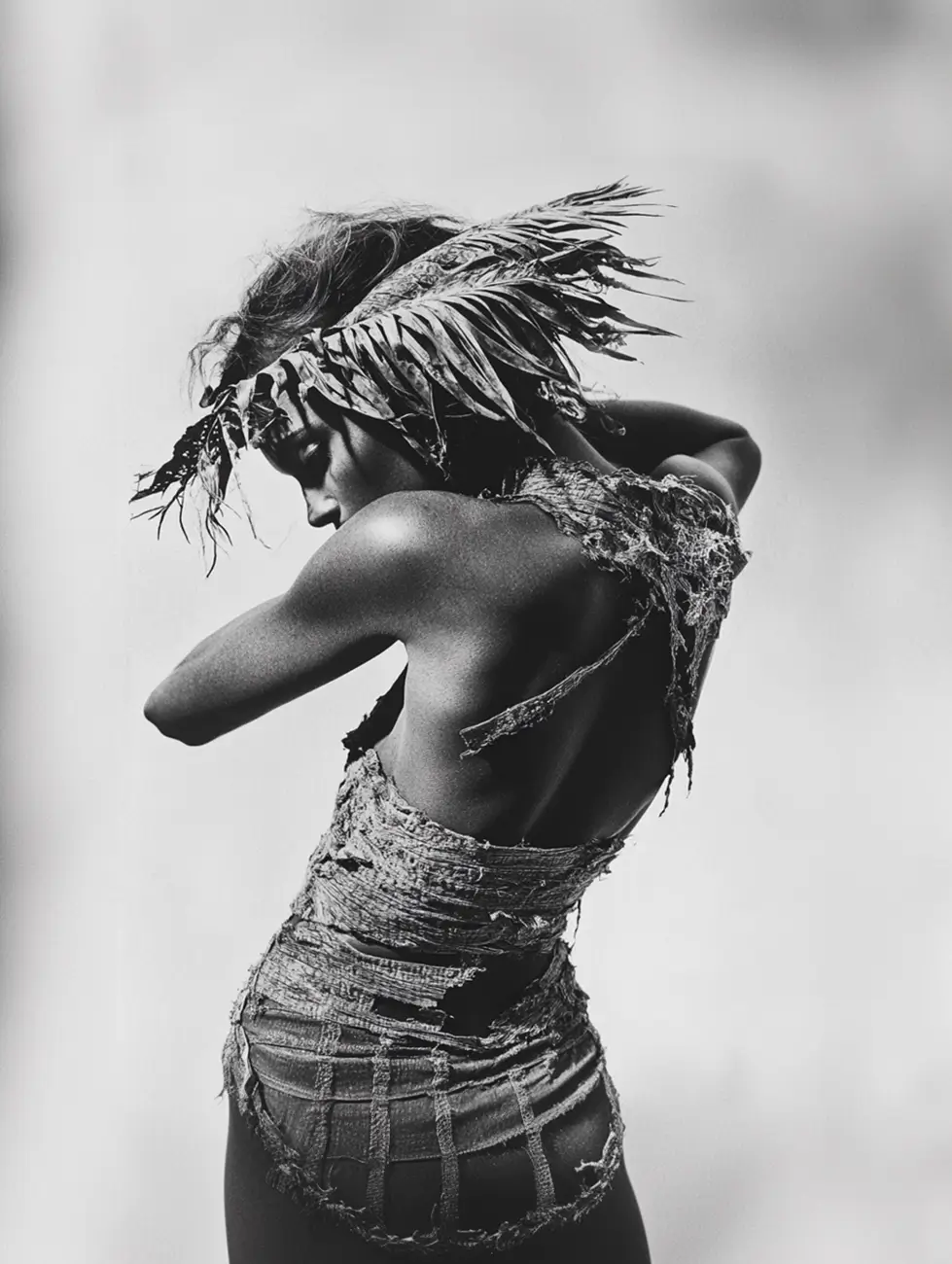

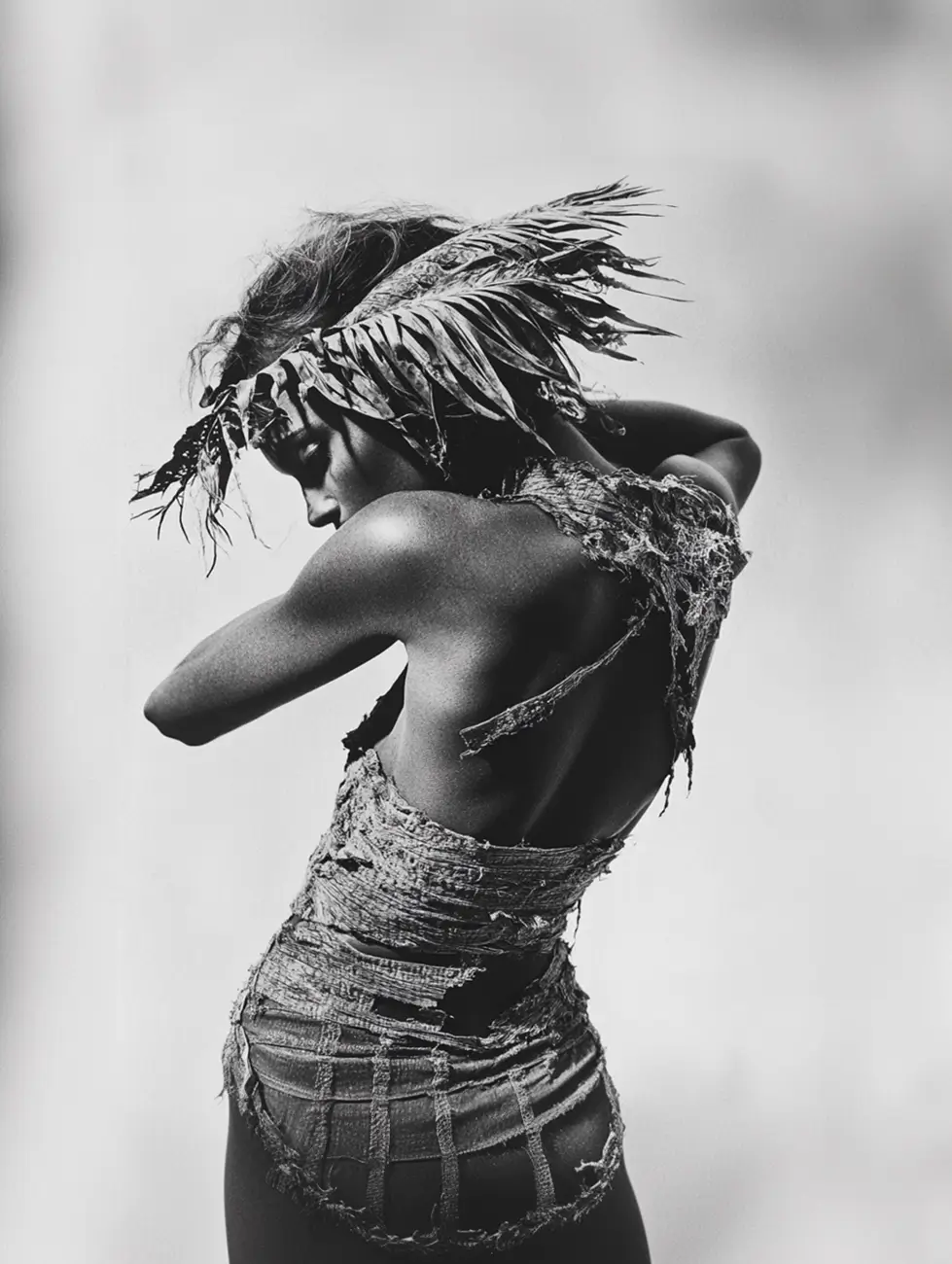

© Besse Manuel, Agence Posto 5, Sur la terra de Nod 2025

In recent months, I have been focusing all my energy on three areas. The first is the

continuation of Nod, a long-term photographic series begun in Rio that explores the dignity

of invisible lives in the favelas and urban margins. It is a project that is built over time:

returning, staying, walking for long periods, forging links until the images bear the traces of

this immersion.

At the same time, I am preparing a fiction film entitled Sur la Terre de Nod, which is

scheduled to begin shooting at the end of 2026. This film will extend the photographic project

by blending reality and fiction to tell the story of internal exile, the quest for refuge, and the

wandering that runs through so many human trajectories. I want the viewer to feel the

intensity of this endless journey. The sovereignty of the faces, the light, the postures, and the

perceptible hope of those who still live on the margins.

Finally, I am working on the creation of POSTO 5, an independent reporting agency. It is a

project deeply rooted in my vision of photojournalism, pushing me to return to the source, to

the early foundations of the Magnum photo agency. A collective and demanding structure

where highly talented photographers, each with a strong and unique style, will be able to

work in complete freedom. POSTO 5 will be a space of independence aimed at producing

long-term reports, far from the editorial constraints that too often sanitize reality.

As in Magnum's early days, the idea is to put the photographer back at the center, to give

them the time and means to portray the world with honesty and depth. These three projects,

Nod, Sur la Terre de Nod, and POSTO 5, are in fact part of a single commitment.

Documenting fractures, making visible what has been erased, but also revealing the beauty

of the world, like a painter, in places where we no longer look. It is a work of terrain, light,

and breathing. It is a way of saying that despite the chaos, humanity persists.

Are there any upcoming journeys or themes you're eager to explore

next? What does the future hold for your photography?

My recent projects, such as Nod, have confronted me with realities of extreme emotional

intensity. For months, I immersed myself in the reality of Rio's favelas, those margins of the

world where people survive rather than live. Each face I photographed bore its own grief,

and I carried them all with me. Little by little, I felt something crack inside me. This weight

settled silently, almost like depression creeping in without warning.

From this observation, Sur la Terre de Nod was born, the fiction I am preparing for the end of

2026. It extends the heart of Nod while opening up another way to tell the story of inner

exile, the loss of bearings, the wandering that I saw in others and was beginning to feel

within myself. This project is a way of transforming pain into narrative, of giving form to what

would otherwise have consumed me.

I understand today that my balance as a photographer must evolve. I must continue to

document the fractures of the world, yes, but without becoming engulfed by them. My

photography must remain anchored in reality, but it must also breathe, let in light, let in the

vital impulse. I need to find spaces where humanity reveals itself in its strength as well as its

fragility, so that my gaze is not only that of a witness from the shadows.

This is also what drives me to create POSTO 5, an independent agency inspired by the spirit

of Magnum's early days. A collective that will carry out coherent, demanding, and free

projects, capable of combining documentary rigor with creative audacity. If I had to define the

future of my photography today, I would say this: I want to continue to confront the world and

its fractures, but learn to come back from them. To bear witness without breaking, to

transform pain into form and strength.

© Besse Manuel, Agence Posto 5, Sur la terra de Nod 2025

Take your time. Not five minutes. Not an hour. As long as it takes. Walk, wait, let the places

and people come to you. Stay open to anything. A meaningful image cannot be stolen. It

must be earned. You have to accept anonymity, silence, sometimes even boredom, until the

world truly reveals itself.

Remember that black and white is not an effect. If you choose it, it must be out of necessity.

It does not forgive the easy way out. It strips away. It lays the world bare. In its contrasts,

every detail counts: a wrinkle, a breath, a shadow that is too harsh. Black and white requires

a sincere gaze, capable of translating what we feel more than what we see.

Have deep respect for those you photograph. No gratuitous staging. No sensationalism.

Listen before you shoot. Speak little. Look a lot. Trust is built. Or it is not built. And without it,

an image remains an empty shell.

Your place is on a knife edge, between documenting and revealing. Reality is there, raw. But

it is up to your gaze to infuse it with resonance, with strength, without ever betraying it. It is

an inner commitment. An ethic of the gaze. Being there completely. Carrying what you see.

And accepting that each click of the shutter engages both your responsibility and your

sensitivity.

The rest? Awards, likes, recognition? Forget it. If your image carries a grain of truth, it will

stand on its own. And that's all that matters

Anything else you would like to share?

Yes. I would like to remind you of one thing: photography is not a career, it is a commitment.

We don't take photographs to fill walls with images; we take photographs because we need

to understand, to bear witness, to leave a trace of what would otherwise disappear without a

trace.

Today, the world rushes, consumes, erases. Images flash across our screens as if they were

disposable. But a good photograph can withstand all that. It survives fads, time, and oblivion.

Not because it is “beautiful,” but because it carries within it a grain of truth, a human charge

that nothing can replace.

To those who read me, I would say: don't give in to the easy way out. Don't let networks,

numbers, and trends decide for you. Walk, observe, doubt, come back. Take the time to earn

your images. A photograph that matters is one that you don't let go of, because it changed

something in you the moment you took it.

Finally, what I would like to share is a conviction. Photography is not just a way of looking at

the world, it is a way of inhabiting it. Every image, if it is sincere, is a fragment of resistance

against erasure. I will continue to move forward, to document this battered world, but also to

seek out the light, like a painter, even in its darkest corners. Because ultimately, that's what

matters to me: reminding people that there is still something worth saving.

© Besse Manuel, Agence Posto 5, 2024

© Besse Manuel, Agence Posto 5, 2025