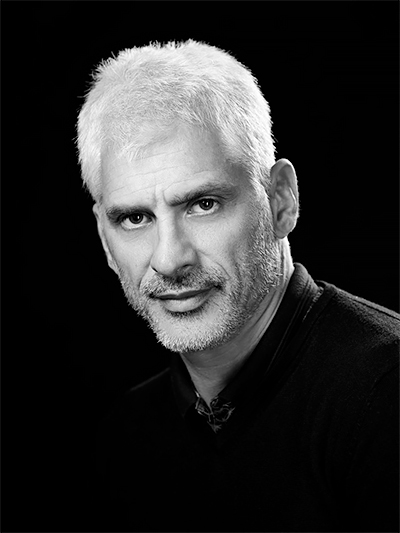

Stephan Gladieu began his career in 1989, covering war and social issues, travelling throughout Europe, Central Asia and the Middle East.

Reporter in his early days, very quickly used the portrait to illustrate the human condition around the world.

Today he still produces reports and portrait series for international magazines, but he focuses mainly on his personal and artistic work through portrait series whose DNA is the colour and rigorous composition.

He likes the iconic character of an image, its frontality, its readability and the boundary between real and unreal.

His last series are mainly done in Asia and Africa.

Nowadays, Stephan Gladieu's work is published in leading publications in France and internationally.

Stephan is represented by Olivier Castaing, owner of the

SCHOOL GALLERY, in Paris.

We asked him a few questions about his life and work:

All About Photo: Tell us about your first introduction to photography?

Stephan Gladieu: It was painting that led me to photography, the golden age of the 17th century Dutch paintings. I remain fascinated by the portraits of Vermeer, Rembrandt, Hals, the paintings of Saenredam and van Ruisdael.

The work on light fascinated me, it led me to photography which seemed more affordable to me because of my poor drawing skills...

Who were your biggest influences?

First I discovered Robert Doisneau, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Man Ray and then André Kertész whose contrasts and composition still fascinate me.

Later I started to take an interest in Horst,

August Sander and Diane Arbus.

The work on August Sander's identity has taken on a particular importance over time.

As well as the color schemes of

Martin Parr or Alex Webb. And finally I think of Tim Walker for his colorful and phantasmagorical universe.

Why did you decide to cover wars and social issues?

I didn't really decide, it was an accident.

I lived in a poor suburb and one day, in an old car, my father took me across the iron curtain between Western and Eastern Europe.

I was 12 years old and we were going to have a serious accident in the middle of Ceauscescu's Romania's countryside.

This accident, the first, plunged us into the daily life of the country and opened a gateway to another world, to others and the richness of our differences. I discovered dictatorship, poverty, the strength of the resistance fighters' souls, difference and solidarity. I was a child but it profoundly changed my view of the world.

Later in 1992, I went to Afghanistan for a long expedition to meet the Kyrgyz people on the edge of the Wakhan. But the civil war started while I was on the plane. I had a choice, to leave again or to cross this border.

I was then helped by Steve Mc Curry who made his local assistant available to me to prevent my stubbornness from costing me my life.

The war came, I was naive, I thought I was escaping it. She grabbed me, swallowed me and spit me out.

What was the best piece of advice you were given starting out?

Never refuse a job, never, there's always something to learn! Thank you David Turnley. Then in continuity, never refuse yourself anything, the others will take care of it well enough for you, be free, at all costs!

Do you think that a picture can be an antidote to war?

If we're talking about a substance that can prevent from toxic effects, I don't think so!

There's no antidote to war. War destroys everything, your mind, your soul. I mean, if you were lucky enough to survive.

Photography makes it possible to testify, immediately, to denounce a tragedy and to anchor it in the collective memory. But certainly not to prevent it.

Photography has curiously been an antidote to the perception of violence. The scenes I couldn't photograph remained much more present in my mind than those photographed. As if the camera was protecting my unconscious.

You have traveled in many countries, is there one that marked you more than others?

Afghanistan, the Afghans are absolutely incredible people, the landscapes are of a mad intensity and I only felt this powerful energy in New Zealand. On a personal level, I arrived in Afghanistan as a kid, I left being who I am today. This country has completely changed my life and my destiny.

Do you remain in contact with the people you photographed?

Robert Franck said that to take a good picture, you have to assume that you are a misanthropist, that he didn't like talking to his subjects. I talk to my subjects, I make contact with them whatever the context but I rarely stay in touch with the people I photograph. I am just a medium.

Why did you choose to photograph North Koreans?

North Korea has always been an enigma and one of the most hated countries in the world. And it is also one of the most underestimated.

It is obvious that the radicality of this paradox hides a more complex reality than we are given to read. War, famine, dissidents, the nuclear program...

But what about its population, its twenty-five million North Koreans? Who are they? In this permanent context of political, diplomatic and military crisis, the North Koreans are made invisible by the propaganda of a dynastic and dictatorial regime. Yet these people are undoubtedly the main key to my questions. Why has this regime, cursed by many, never wavered?

Even after the fall of the communist bloc, which nevertheless ensured its political and economic stability; even despite international attempts to suffocate it; even after successive economic, climate and food crises; and despite the control and repression exercised over a population.

Could a single man, a single party, a single dynasty, alone guarantee the survival of this regime without the deep and singular nationalism of its people?

I wonder about the identity of these people and its link with the tragic fate of this nation.

How did you prepare for this trip?

Even before leaving, I knew that I would be accompanied every step of my stay and that the existence of this series would depend intimately on the relationship with my hosts. Without mastering the language, without choosing my movements, I had to invent a framework of freedom within the framework that would be imposed on me and would constrain my creation.

How to reconcile my vision, my projection of a Westerner and the perception my hosts would have of this proposal. For each person randomly arrested in the places they had chosen to show me, what would be the lowest common denominator that would allow them to allow me to do their portrait, without them losing face?

What were the codes, situations, profiles they would consider presentable for my purpose. It was essential that they find understandable, acceptable referents in my work. Our worlds, our cultures, our mentalities are so different, that understanding us has often required intense efforts from their parts.

I chose the mirror portrait, captured in the most raw frontality, as an anthropological frame of reference. I wanted to follow in the footsteps of the scrupulous August Sander who mixes documentary photography and artistic practice. In his portraits, the light is constant, the view is frontal, the direct view, the frame varies very little. The model settles into his portrait, takes care of his appearance as he wishes. The photographer will not try to surprise him.

Did you travel alone?

On my personal projects, I like to travel alone, I prepare the project a long time in advance and I try to find the best local intermediary. It is always the highlight and the key moment of the trip because the quality and power of this meeting has an important impact on the project.

On this project it was particular because it is impossible to move alone or to choose your intermediary.

I had two people with me all the time, so we had to get to know each other and find common ground.

Did you finance the project or was it commissioned?

I finance all my personal projects, it is essential to maintain total freedom.

What was your biggest challenge?

The biggest challenge was to face the North Korean, to start a dialogue, to succeed in exposing my project, to make it understandable to them and to create the precondition for a relationship of trust and to make it grow over time.

It is not a spectacular and immediate challenge but a fine, long and complex process.

Because you know, the cultural difference that separates us is abyssal. I'm not talking about politics, that doesn't interest me.

Only those who are enslaved by it touch me.

Where you able to photograph freely?

From the moment I was in places that had been validated, I was quite free. In the streets, I had more freedom because they were more confident about me.

But this freedom is all relative for us because you cannot move freely.

How did people react to your camera?

Look at the portraits, look at the expressions of those I met, I hope you will feel their reaction a little.

I had the feeling of experiencing, to a certain extent, what Edward Curtis must have felt, being a pioneer in Terra Incognita, in the presence of a little-known people who were untouched by any photographic relationship.

I realized that as I was a revolutionary who introduced the individual portrait for the first time in North Korea and that on the other hand the sticking points that I imagined were not where I expected them.

Are there images you wish you could have taken but you couldn't?

Yes, of course, as everywhere else. But for this portrait series project, yes, I would have liked to have photographed elderly people and men and women who go beyond their beauty criteria.

Because for the people I'm going to photograph during these different trips, their beauty will be at the centre of all discussions, the elderly are ugly by definition. Photographing them is a battle. An ugly person knows that he is ugly. So asking her to be photographed means placing her in front of her ugliness and thus making her lose face. It is amoral to lose face. So we won't ask the ugly to stay moral Well at least that's clear to me! The next one...

The dirty trades are not popular either, farmers, metallurgists, miners... Next!

It is essential to understand that, in Korea, to be visible, the object must be completed, perfect, aesthetic and to be a source of national pride.

But it's not political, it's purely cultural, you find the same obsession in South Korea.

Here this has of course been scrupulously applied in the visual communication of the regime

What equipment do you use?

The choice of equipment depends on the series I make, I choose according to the shooting conditions and my feelings. For this series, I used a Nikon D850 with one lens and 2 or 3 flashes Prophoto

Do you spend a lot of time editing your work?

For such a series of portraits, I don't spend much time, I prepared the work beforehand and I know from the moment I take the picture what photographic material I have.

Some stories and in Black and white others in color, what determines your choice?

There are differences in treatment in each of my series even between those in colour. I don't like to do exactly the same thing again. I think about the colour of the story beforehand, I exchange with Camille with whom I do the post-production and we do tests according to my feelings.

What makes the difference between a good image and an iconic image?

An iconic image is distinguished by a frontality, a readability that is unambiguous... and yet the icon is only a relationship of resemblance with reality.

It maintains the mystery of the border between the real and the unreal.

This is probably why the iconic image fascinates so much.

What compliment touched you the most or what do you think is your biggest accomplishment?

You have a shitty character, you never give up but well... you're honest!

What advice would you give someone who would like to become a photographer today?

To consider that it is not a profession. It is a priesthood, a real choice of life that therefore involves significant sacrifices.

The profound and rapid technological evolution has led to the disappearance of a large number of references, but I believe that photography remains the art of shooting, the ability to capture a moment.

Forget technology and post-production, concentrate on the viewer and everything happens there!

And be free to censor yourself during editing.

What mistake should a young photographer avoid?

To think he's a photographer!

Learn to become one, observe and question yourself

I believe that the feeling of certainty heralds the end of the creative adventure

What are your upcoming projects?

A work on African mysticism, on the link between the dead and the living.

If you weren't a Photographer, what would you be doing?

Probably a thug, a smuggler, as elegant as possible but still...

Stephan Gladieu will be at

The Rencontres d'Arles, his project

North Koreans will be on view at the Chapelle du Méjan. Opening week June 29 - July 5, 2020. Festival June 29 - September 20, 2020

The Book will be published at

Actes Sud in June.