Heinrich Rudolf Zille, born 10 January in 1858 in Radenburg near Dresden in

Germany, is famous, though unless you live in Berlin, you may not have heard of

him. An artist, lithographer, cartoonist and lecturer, his street photography is

among early examples but was almost unknown until rediscovered in the 1960s.

What is noteworthy about them is that they are the work of a man of the

proletariat who photographed fellow Berliners of that demographic. They are

contemporary with the candid photographs that

Paul Martin made on the

London streets using a hidden camera.

Both arrived at photography through their work as part of the vast army of

people illustrating the popular picture press, Martin as an engraver, and Zille as

a lithographer, a profession suggested to him by Max Libermann.

© Paul Martin (c.1890)/ Courtesy Luminous Lint

(c.1890) Blind beggar at the cattle market. Platinum print 18 x 22.8

cm Victoria and Albert Museum

Both started photographing well before

Lewis Hine (1874 - 1940) and about

the same time as

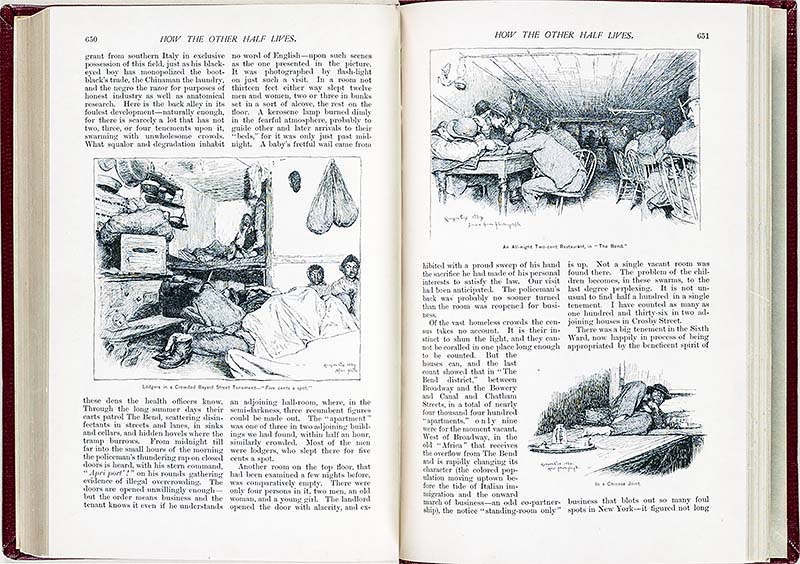

Jacob Riis (1849 - 1914), also a newspaper employee and at

one time the owner of the News who had started his well-known project

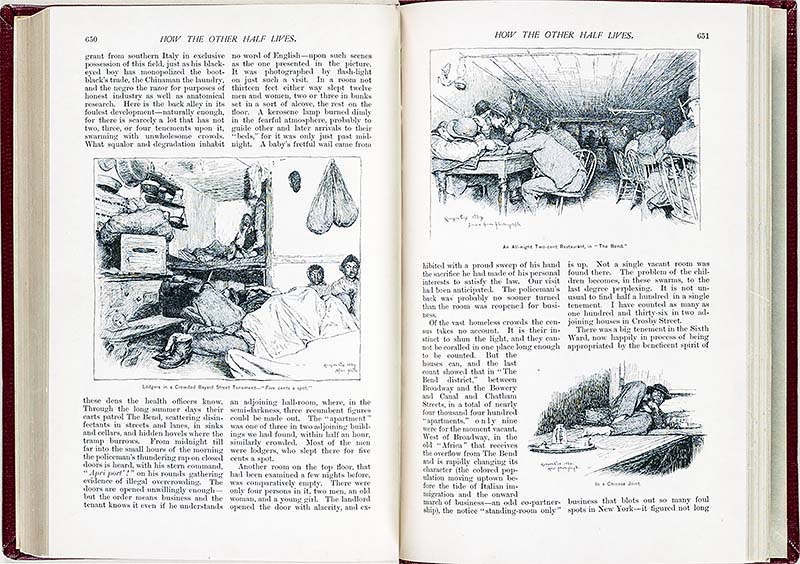

How

the Other Half Lives in the tenements of New York with an eighteen-page

article in the Christmas 1889 edition of

Scribner's Magazine.

'How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements,' wood engravings from photographs, Scribner's Magazine, December 1889. Library of Congress

Zille was celebrated in his own lifetime (he died in 1929) as a cartoonist and

graphic artist and with the post-war division of Berlin and start of the Cold War

his reputation was claimed by the communist state. He lay claim to the

working-class subjects of the poorest districts of north and east Berlin, as

'Mein Milljöh' (My Milieu), justifiable because of his origins in a modest

provincial family of Saxony who, to escape his watchmaker father's debts, had

migrated to the city in 1867 just as did millions of others to live in the then

densest concentration of tenements in Europe amongst which they found a

basement near the Silesian train station. At nine years old, and with his father

back in jail, he earned a living delivering newspapers and running messages,

quickly familiar with 'Dark' Berlin of the rapidly developing civil servants and

industrial city.

Ignoring his father's advice to be come a butcher, in the 1870s he used his skill

in drawing to train and got work at the Photographische Gesellschaft,

specialists in popular reproductions of artwork, and began exhibiting his own

work in the form of drawings and prints in 1901. Zille was encouraged exhibit in

the Berlin Secession recently established in 1898 by

Max Liebermann

and sculptor friends

August Gaul and

August Kraus, both of whom were

members and there he exhibited alongside others who so vividly depicted the

proletariat,

Hans Baluschek and

Käthe Kollwitz, and illustrators of urban life

like

Theophile Steinlen and

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Unlike Kollwitz,

Zille's imagery rattles with the same ironic laughter as did his poverty-stricken

urban subjects in confronting their sorry lot.

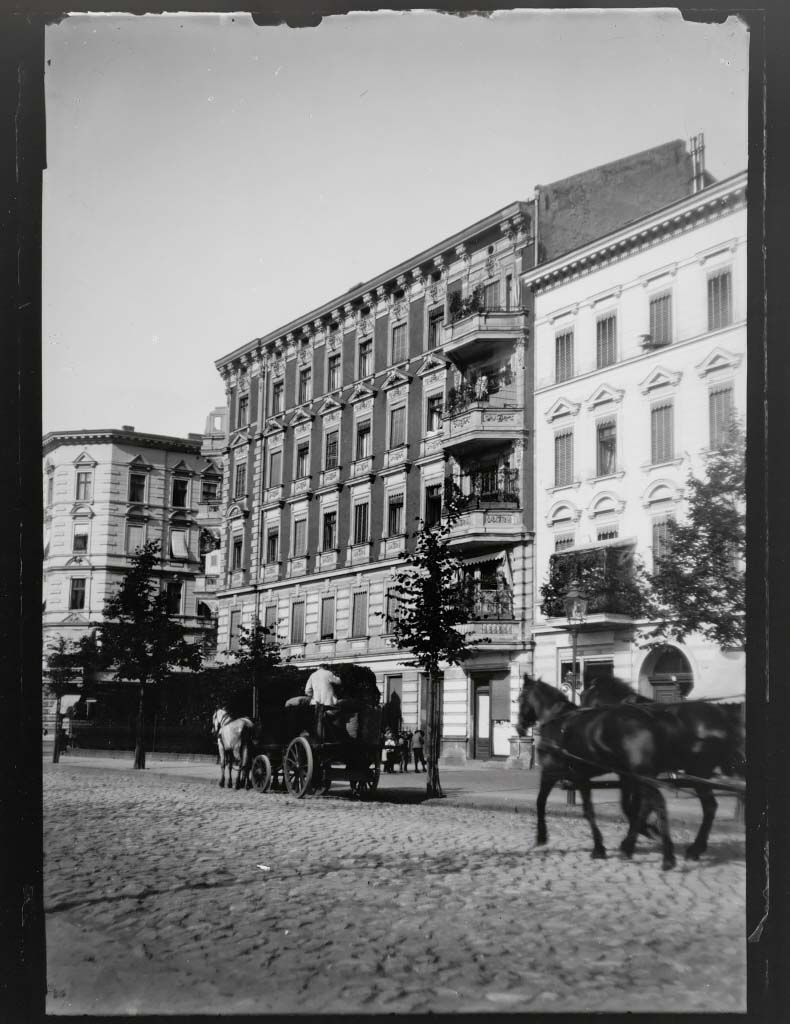

Zille followed the Photographische company in 1892 to new quarters

in increasingly bourgeoise Charlottenburg in NW Berlin,

the population of which tripled between 1890 and 1920.

He established his young family there, where he spent the rest of his life,

climbing socially above his original 'milieu' but, following his sacking from the

Photographische Gesellschaft and his subsequent career as an illustrator, he

continued to cultivate an identity as a proletarian artist, albeit one that drew on

his own hard experience and genuine empathy.

Heinrich Zille (after 1893) Zille family in their Charlottenburg apartment

Heinrich Zille; Friedrich Luft (1967) Mein Photo-Milljöh : 100 x Alt-Berlin. Publ. Hannover : Fackeltr ger-Verl. Schmidt-Küster, 1967

Interestingly, in 2013, Dresden photographer

Detlef Zille (not related to

Heinrich) published a

thesis that fiercely disputes that Heinrich ever was a

photographer, against the view expressed in Berlin Theater critic

Friedrich

Luft's publication of the first 120 images discovered, in his Mein Photo-Milljöh,

and artist

Matthias Flügge's

Das dicke Zillebuch,curation of two large Zille

exhibitions in 1996 and 2008, and a catalog raisonn of the prints.

He dismisses daughter Margarete K hler-Zille's memories of her father taking

pictures, attacks the credentials and motives of authors of books on the Zille

photo archive, finds inadequate written evidence, implies that the discovery of

the negatives in the apartment of the artist's step-grand-son was fabricated for

financial gain, and obliquely insinuates that some may have been 'flea-market

finds.'

Is this a case of stubborn denialism? As

Aaron Scharf has shown in his 1968

Art and Photography, with others since corroborating, there is a common

resistance amongst painters, and their biographers and descendants, to admit

a resort to photography, or at least keep it a 'trade secret' - witness the

apoplectic tantrums of certain art historians around

David Hockney's Secret

Knowledge: Rediscovering the lost techniques of the Old Masters. His

reputation as Heinrich "The Brush" Zille was too good to endanger with any hint

that he might resort to mechanical aids!

The proof of course was always there in the photographs themselves, the

cache of over four hundred glass negatives and approximately one hundred and

twenty original prints discovered in his estate in 1966. They are dated 1882 -

1907, when Heinrich Zille would have learned to operate copy cameras and

darkroom at the Photographische Gesellschaft, and had opportunity to process

his negatives and the contact prints which survive.

In 1987 the Berlinische Galerie succeeded in acquiring Zille's entire

photographic estate, 152 original prints and more than twice as many glass

negatives, and all can be freely viewed there online, which I have done in

preparing this post. The Galerie commissioned photographers Michael Schmidt

and Manfred Paul to make new prints in 1993/94, boosting the entire Heinrich

Zille collection to 628 records, though it includes 85 photographs that they

identify as by an 'unknown photographer' but which Zille kept.

Heinrich Zille (after 1893) view from the window of the Charlottenburg apartment to the southwest (Zeno photography)

The subject matter is clearly linked to Zille's interests. A view from the

apartment window shows an open vista across a sandy plain toward the

Ringbahn (railway) with the Knobelsdorff Bridge to the southwest as early as

1893.

Four years later, and we are with him as he photographs back toward his

apartment (below the arrow)

The women in the foreground of his photograph are labouring to push a

converted pram through the sand and tracks left by others doing the same;

carting sticks from the distant Spandauer forest to use for heating and cooking

in their tenement, or to sell.

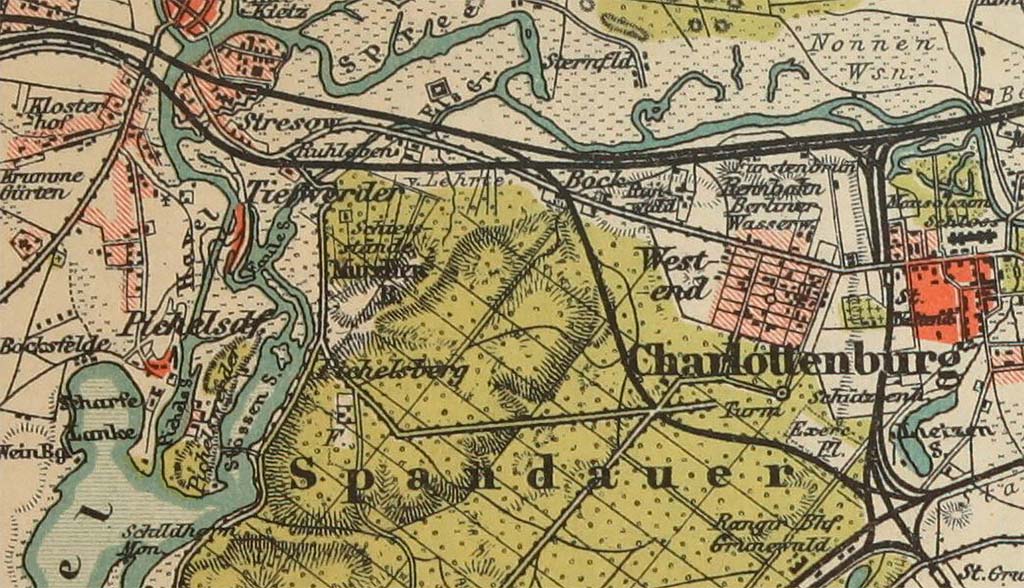

Map of Charlottenburg in 1900, showing the West End location of the Zille

apartment from which they had a view to the east.

Like the washing strung in the open space below his window, these women and

their labour presents a subject that clearly fascinated Zille, one depicted in his

cartoons and prints.

Heinrich Zille (1895) Autumn. Original etching (etching and aquatint in brown black on yellowish vellum. 13.8 x 23 cm

Heinrich Zille (after 1893) Brushwood collectors approaching Westend (image flipped horizontally for comparison with etching)

Would it matter if someone else took this picture to his instructions? Hardly;

isn't the cinema director who never uses the camera still accepted as the

author of their films? Aside from the thumbprints embedded in their rather

hastily developed emulsion, that it was he who was behind the camera there is

other evidence fixed in this sequence of rapidly exposed glass plates.

Heinrich Zille (after 1893) Two women with kindling-filled cart

Heinrich Zille (after 1893) Two women with kindling-filled cart

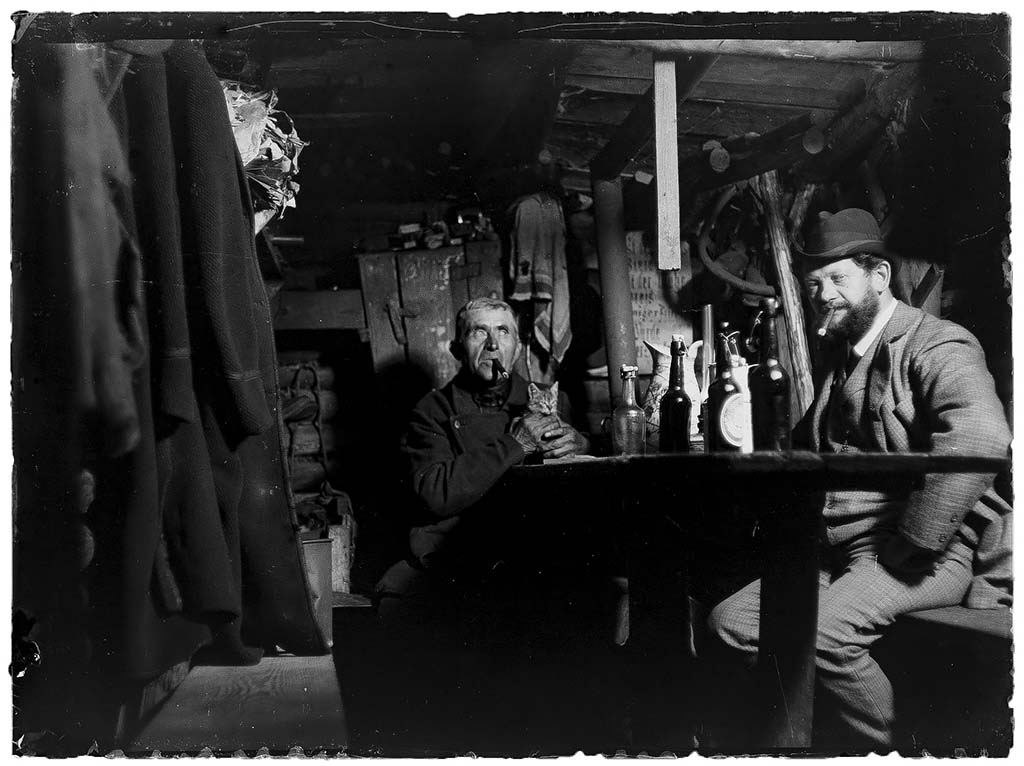

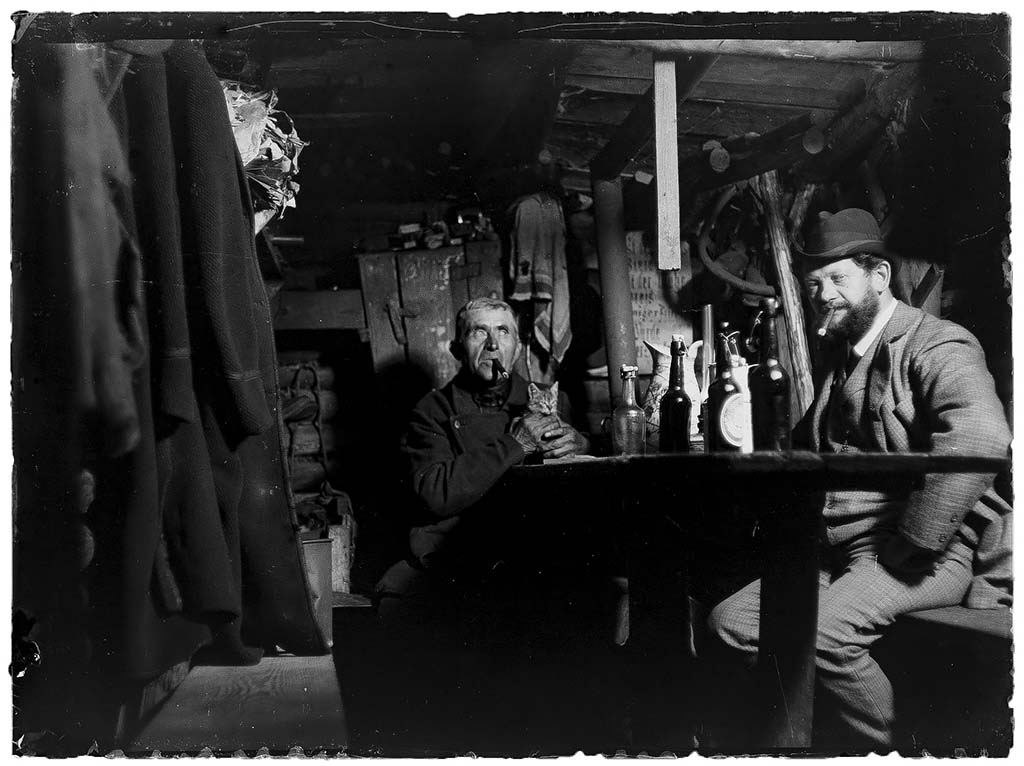

Here's Zille drinking with a gravel-pit watchman. Clearly this is made with a

bulb release with the camera resting on a convenient flat surface for the long

exposure with light entering the doorway which is reflected as a square in the

glass of the bottles; it's not lit with flash powder and its evident that there is not

another photographer present since the other man looks in the direction of

Zille.

Heinrich Zille (c.1900) Gravel pit keeper in his hut with Zille (right)

That characteristic fedora and that bulky Falstaffian figure reappears in the final

shot of the brush-hauling sequence; as a shadow, head tilted downward.

Heinrich Zille (after 1893) Two women with kindling-filled cart

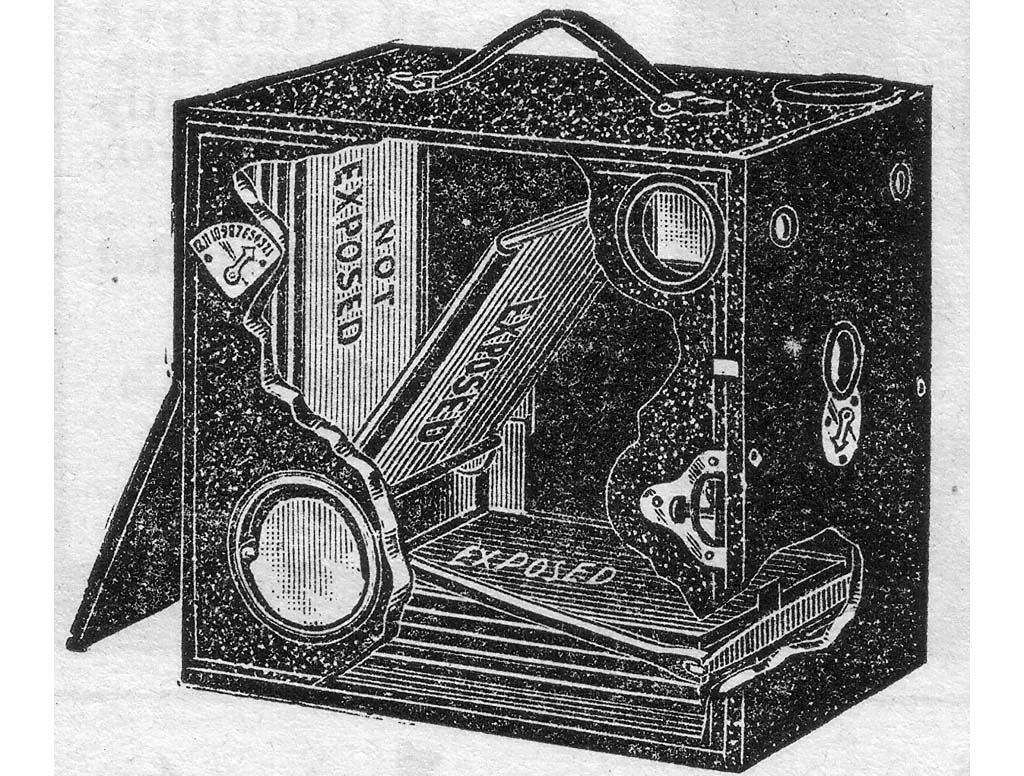

The box camera he is evidently using, is of a common type that Zille like any

middle-class Berliner could easily afford to buy for himself. The horizon crosses

the hips of the two harnessed figures, so we know the camera is being held at

waist level.

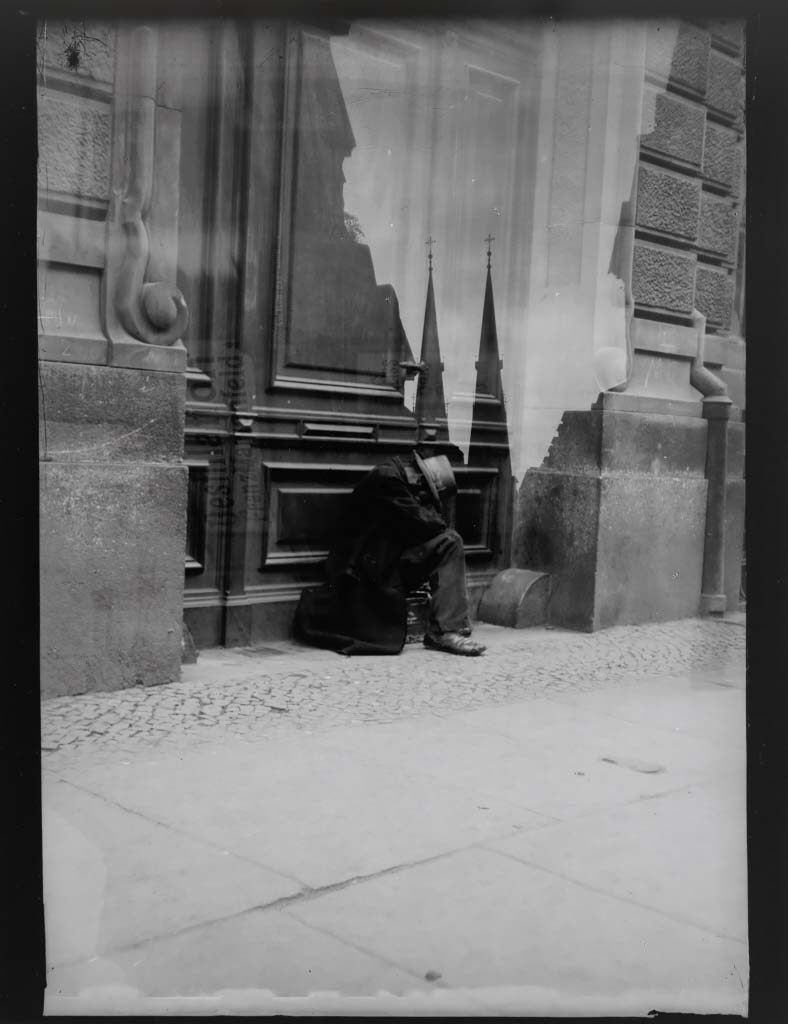

It's a falling-plate camera, of the American Conley 'Quick Shot' type, with a

magazine of twelve 3 1/4 4 inch glass plates in the same format and

dimensions used by Zille, and which could be used to quite rapidly expose a

series of shots.

While it had simple little 'brilliant' viewfinders for either landscape or portrait

orientation (note their position on the box) the camera body had to be turned to

vertical in order to flip down the exposed plate in its holder that was hinged

across the short side, for each exposure. That may account for the left-tilting

slanting horizon common to so many of Zille's pictures, where he has brought

the camera back not quite to horizontal after advancing plates, since it was

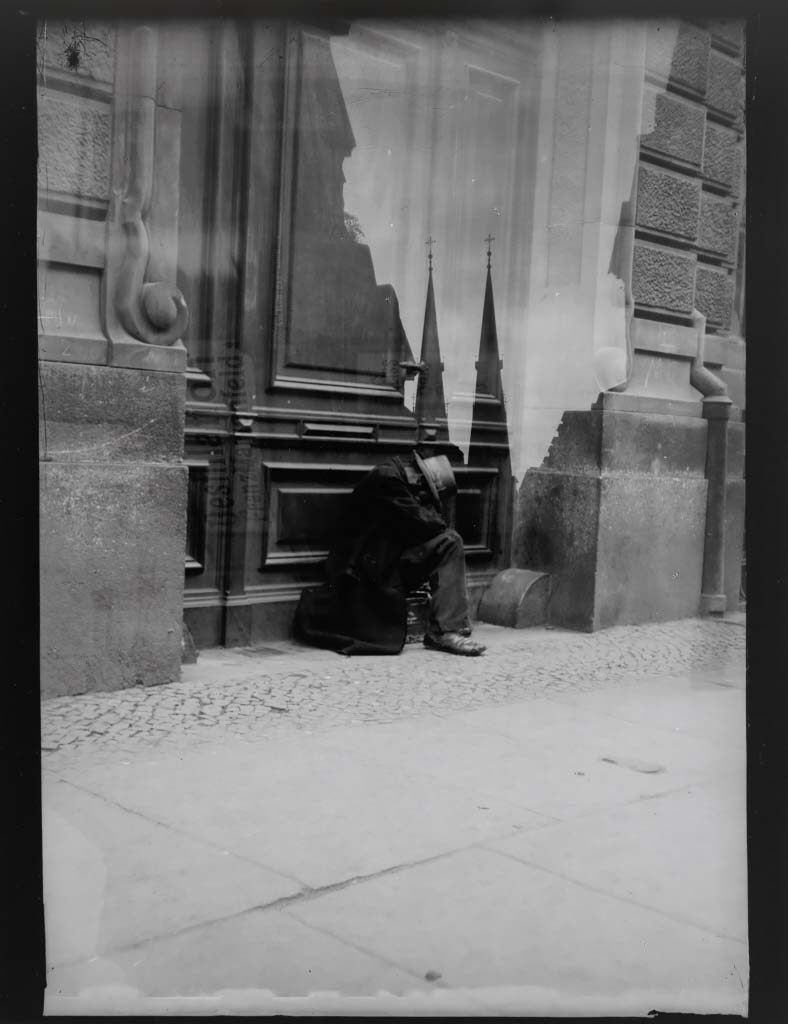

hard to orient with the primitive viewfinder. If he forgot to turn the knob for a

fresh plate, this double-exposure is what would result; in this case the building

facade and cathedral steeples being superimposed.

Heinrich Zille (c.1900) Exhausted man crouching in the doorway of a house.

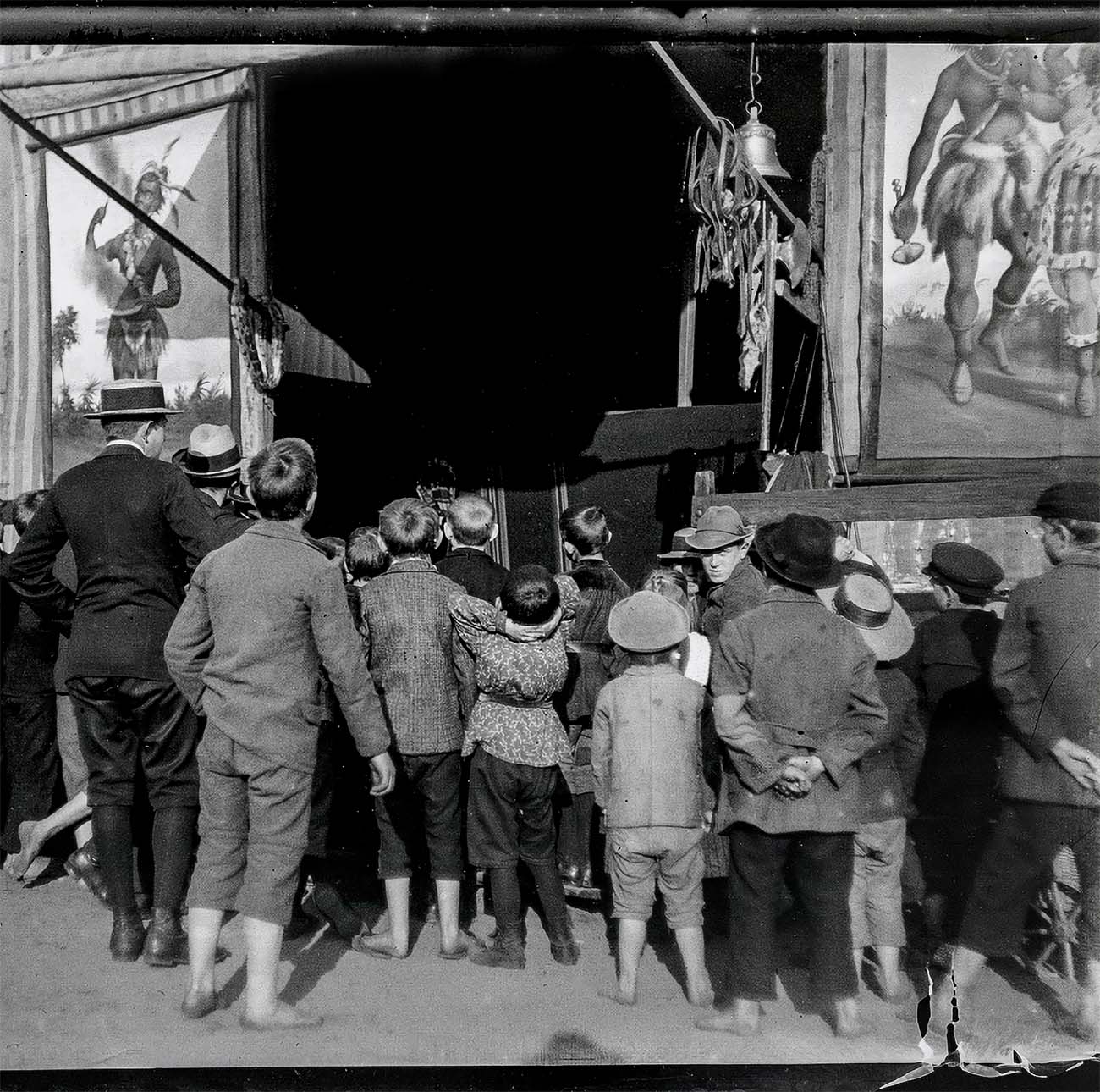

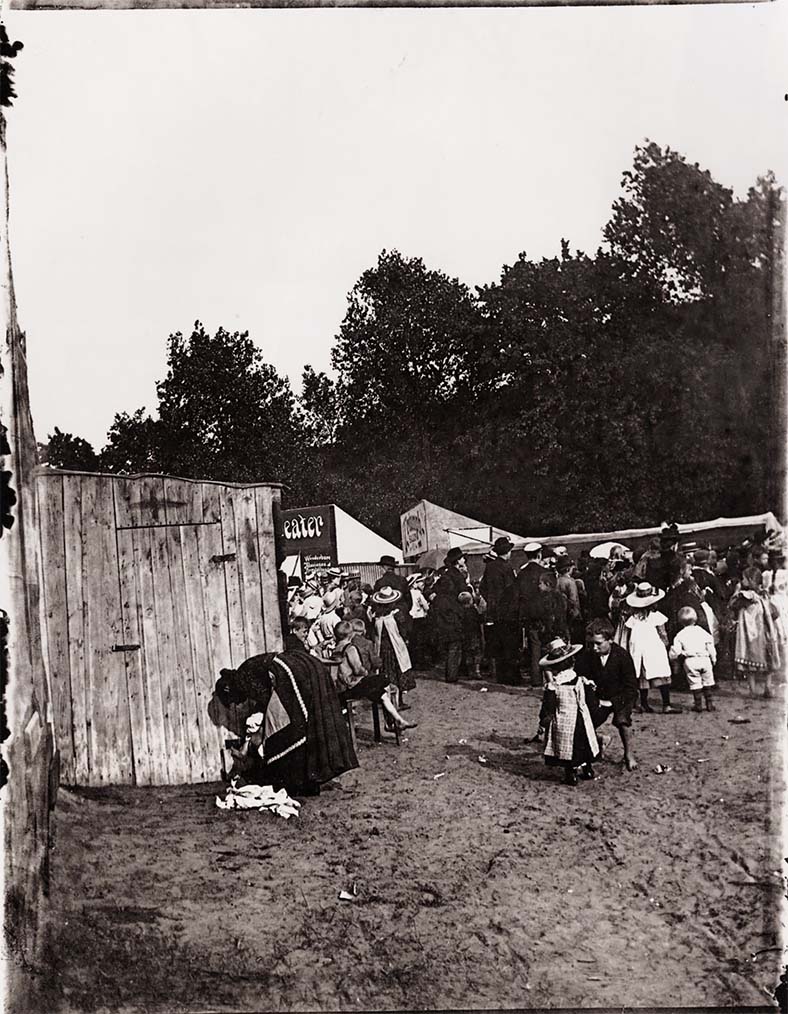

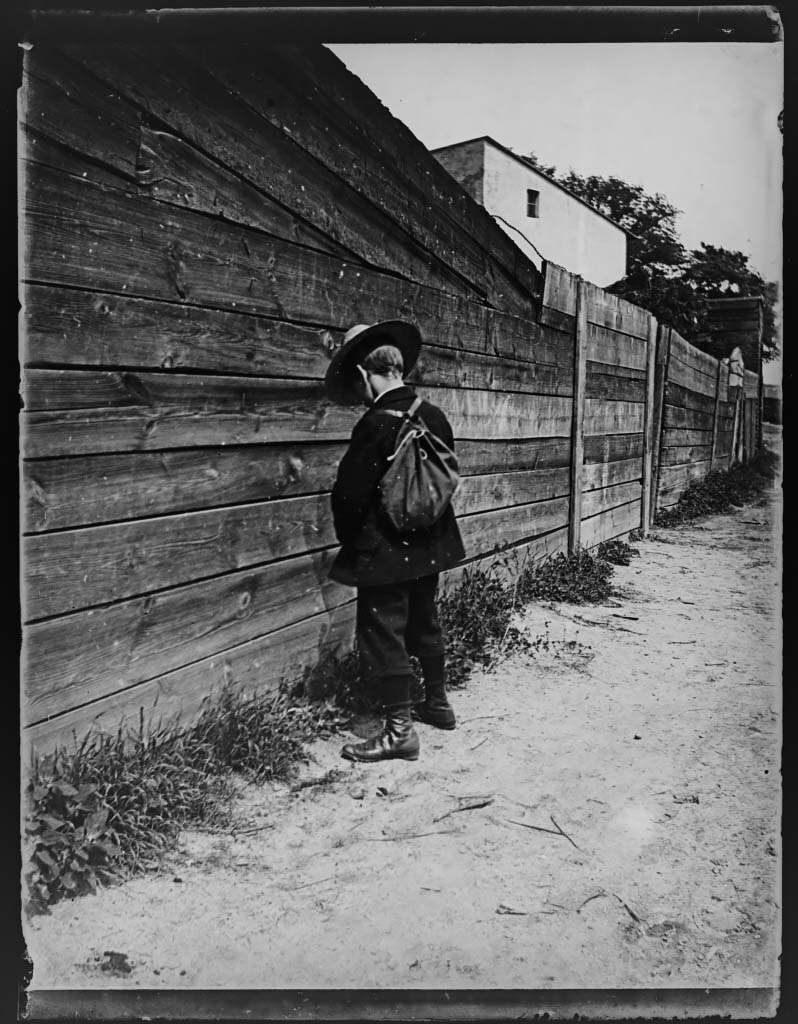

We see Zille closing in on his subject as he walks, as here in a pair of shots

showing a young woman first holding a baby as it urinates on the ground behind

the crowd enjoying a sideshow (realist humour he repeats in an image of his

son pissing against a fence).

He shows her then as she stands, babe in arms, enjoying the entertainment.

And there is that bulky male shadow again, this time hatless. Has he stopped

out of curiosity about her, and she perhaps, intrigued by 'Original Australians'

Heinrich Zille (after 1893) Carnival booth showing supposed 'Original Australians'

Also consistent in the majority of the Zille street photographs is that they were

made with a fixed-focus lens, which results in his selected motif often being

out-of-focus, as here, where the floral dress and the basket weave of the

middle ground is sharp but the stripes of the pregnant woman's skirt in the

foreground is out-of-focus. The lively boys are blurred due to the longer

exposure time needed to compensate for the desired depth-of-field.

Heinrich Zille (1898) Market, Friedrich-Karl-Platz, northwest side.

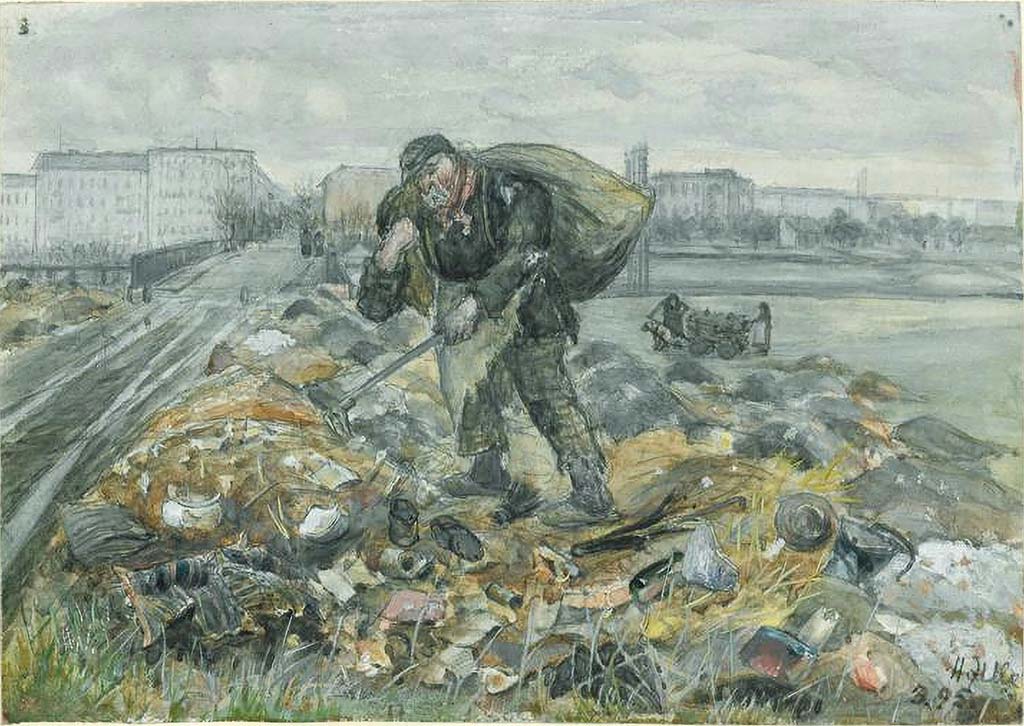

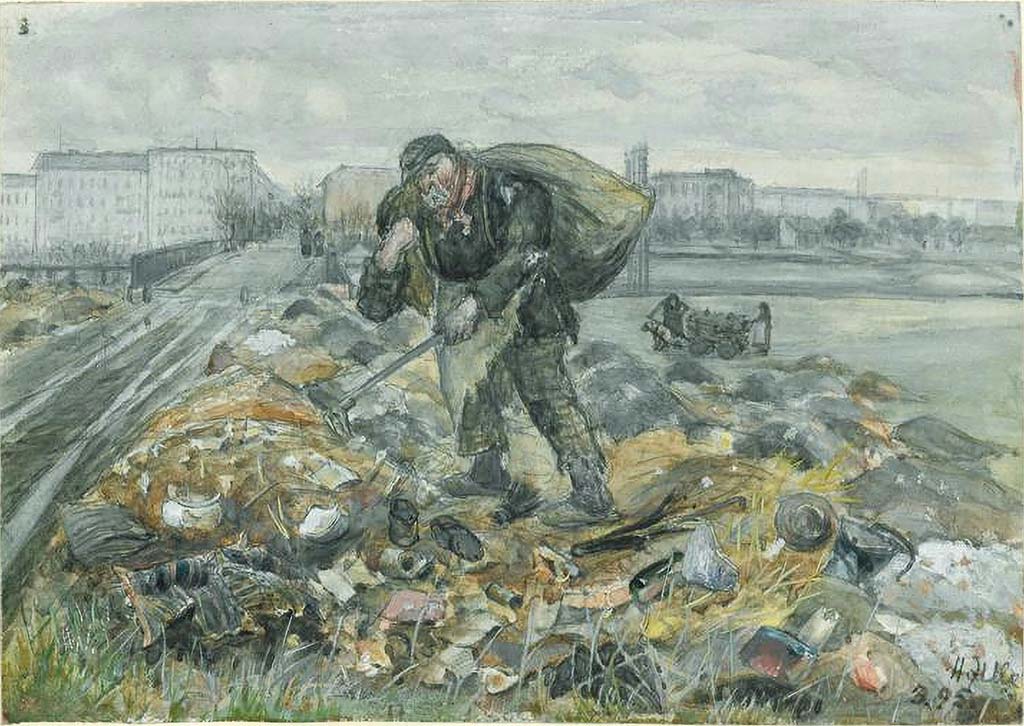

There are distinct parallels between the locations of the photographs and the

places his artworks depict, even those so obscure, unattractive and of interest

to no other photographer, such as this rubbish dump which he has transplanted

close to Knobelsdorff Bridge in the drawing.

Heinrich Zille (after 1893) Garbage dump in Charlottenburg

Heinrich Zille (1895) Muellsammler (Garbage Collector). Drawing and watercolour

Furthermore, there is the attention paid to children in so many of these

photographs, a subject matter that is a major percentage of Zille's oeuvre.

Heinrich Zille (after 1893) children on the Knobelsdorffbrücke, view towards Charlottenburg

Here again, the same back focus too and the stains and unevenness of hasty

processing, and the same format, just cropped square to cut out a stray finger

over the lens.

Zille is a cartoonist, draughtsman, printmaker and painter first and foremost.

Technically, the quality of his street photographs is handicapped by his

amateur equipment and his undervaluing them, but there are amongst his

archive some made with a larger camera and again, the subject matter is

children, this time posing more formally for him.

Heinrich Zille (c.1896) First courtyard in Krögel with posing children, view from the second courtyard

It is also a location of high interest to him; one of the poorest streets in Berlin in

which craft families shared the single building built over a channel into the

Spree, from which their water was drawn. Note the correct verticals of the

buildings in the photograph and the high vanishing point just left of the head of

the most distant man, signifying the use of a tripod needed for the larger

camera and negative, at 8″ x 10″ (26.7 x 20 cm). It is such images, given their

inconsistency with the majority, that one might just argue were taken by a

professional for Zille, but that would give his photography secret away. I can

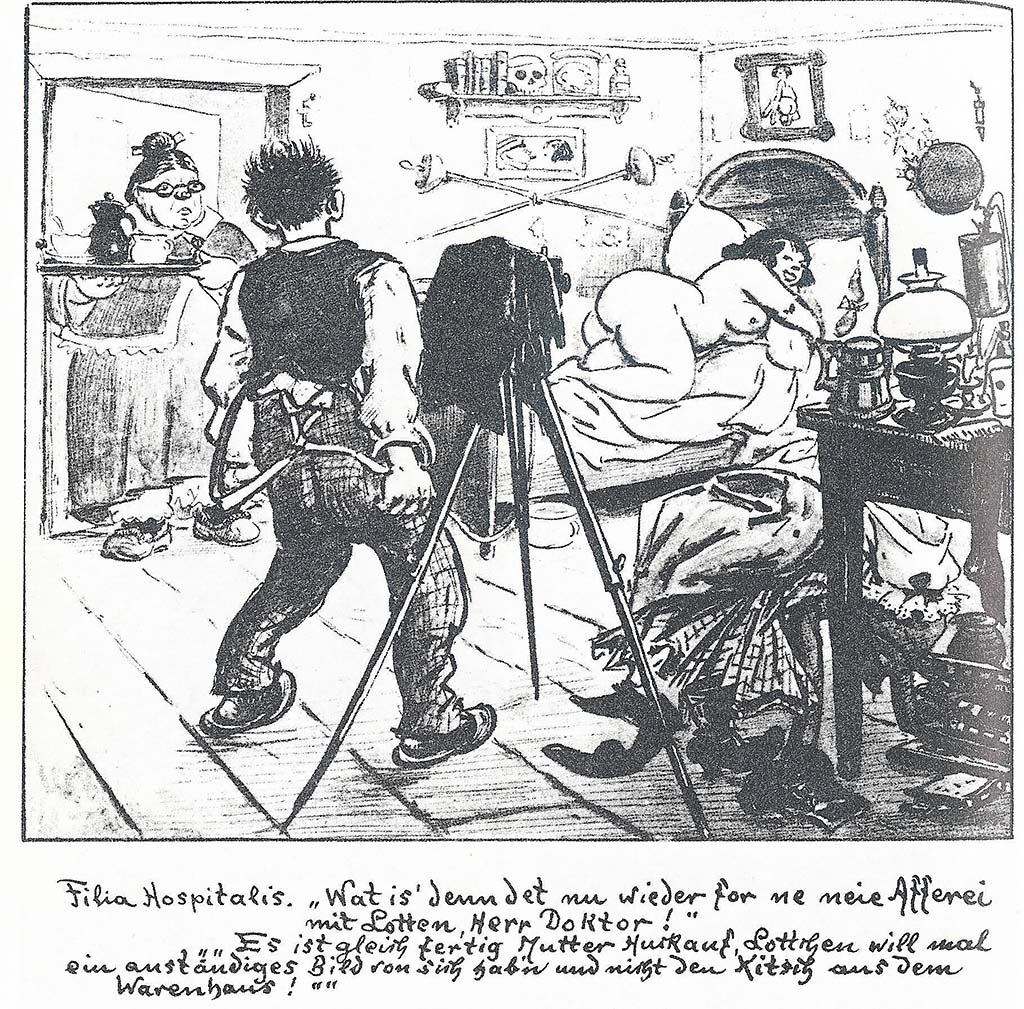

find just one of his cartoons, one from his last years, in which a camera plays a

role.

...which may be interpreted...Landlady: "What's going on with Lotte, Doctor!"

[Medical student lodger]: "It's almost ready, Mother Hurkauff, your Little Lottie

wants to have an authentic picture and not the kitsch from the department

store."

in his 2008 "Heinrich Zille and the politics of caricature in

Germany 1903-1929" (Etudes Balkaniques) provides the most incisive English

language summation of Zille and his context. Of the artist's late career he

notes;

"His contribution to the special issue of Simplicissimus on Berlin in 1926

was a bar scene that could have been from before the war, in contrast to

those of the journal's principal illustrators, each of whom represented a

different aspect of the harsh, brash, contemporary city. Karl Arnold, who

had begun a series of 'Berlin pictures' in the journal in 1921, included Zille

himself in the collection of Berlin types that he presented here. In this

vignette a reluctant looking artist is proferred a box of cigars by a

corpulent, complacent bourgeois and his smart female companion: 'Do take

a fresh Havana Master Zille. You've given us so much pleasure with your

tarts and paupers.' Zille cited this ironic portrayal in a regretful note on the

impact of his work, reproduced in 'Für Alle!. 'I was ashamed, because it was

true.' "

Zille's art, however authentic, can be seen now, against that of fellow exhibitors

in 1912 and 1917

Max Beckmann, Franz Heckendorf, Ferdinand Hodler,

Vincent van Gogh, Ernst Barlach, Erich Heckel, Oskar Kokoschka, Max

Liebermann, Willy Jaeckel, Dora Hitz, and

Edvard Munch, or

George Grosz

later, as complicit in a nostalgie de la boue, the guts of the gutter played for

guttural guffaws. Indeed his erotica indulges in the sordid pleasures of

'slumming it,' with some of his images of naked children verging on child porn.

As a sociological record these photographs serve higher, and lasting, purpose.

One would ignore their contents, style and technique to try to prove they were

not made by Heinrich Zille; that is a folly much more problematic than to accept

that they

are of his eye.

James McArdle

Artist and recovering academic enlightened by the metaphoric potential of focal effects and the differences between human and camera vision.

Academia