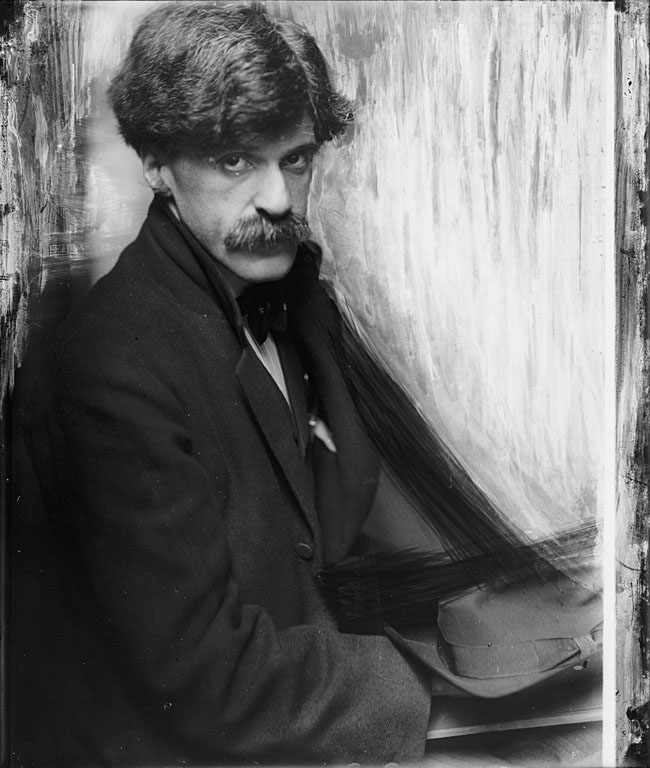

Through his activities as a photographer, critic, dealer, and theorist,

Alfred Stieglitz had a decisive influence on the development of modern art in America during the early twentieth century. Born in 1864 in New Jersey, Stieglitz moved with his family to Manhattan in 1871 and to Germany in 1881. Enrolled in 1882 as a student of mechanical engineering in the Technische Hochschule (technical high school) in Berlin, he was first exposed to photography when he took a photochemistry course in 1883. From then on he was involved with photography, first as a technical and scientific challenge, later as an artistic one.

Returning with his family to America in 1890, he became a member of and advocate for the school of pictorial photography in which photography was considered to be a legitimate form of artistic expression. In 1896 he joined the

Camera Club in New York and managed and edited

Camera Notes, its quarterly journal. Leaving the club six years later, Stieglitz established the

Photo-Secession group in 1902 and the influential periodical

Camera Work in 1903. In 1905, to provide exhibition space for the group, he founded the first of his three New York galleries, The Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, which came to be known as

Gallery 291.

In 1907 he began to exhibit the work of other artists, both European and American, making the gallery a fulcrum of modernism. As a gallery director, Stieglitz provided emotional and intellectual sustenance to young modernists, both photographers and artists. His Gallery 291 became a locus for the exchange of critical opinions and theoretical and philosophical views in the arts, while his periodical Camera Work became a forum for the introduction of new aesthetic theories by American and European artists, critics, and writers.

After Stieglitz closed Gallery 291 in 1917, he photographed extensively, and in 1922 he began his series of cloud photographs, which represented the culmination of his theories on modernism and photography. In 1924 Stieglitz married

Georgia O'Keeffe, with whom he had shared spiritual and intellectual companionship since 1916. In December of 1925 he opened the Intimate Gallery; a month later

Duncan Phillips purchased his first works from Stieglitz’s gallery, paintings by Dove, Marin, and O'Keeffe. In 1929 Stieglitz opened a gallery called An American Place, which he was to operate until his death. During the thirties, Stieglitz photographed less, stopping altogether in 1937 due to failing health. He died in 1946, in New York. The Collection contains nineteen gelatin-silver photographs of clouds by Stieglitz.

Source: The Phillips Collection

My photographs are a picture of the chaos in the world, and of my relationship to that chaos. My prints show the world’s constant upsetting of man’s equilibrium, and his eternal battle to reestablish it. -- Alfred Stieglitz

In early June 1918, O'Keeffe moved to New York from Texas after Stieglitz promised he would provide her with a quiet studio where she could paint. Within a month he took the first of many nude photographs of her at his family's apartment while his wife Emmy was away, but she returned while their session was still in progress. She had suspected something was going on between the two for a while, and told him to stop seeing her or get out. Stieglitz left and immediately found a place in the city where he and O'Keeffe could live together. They slept separately for more than two weeks, but by the end of July they were in the same bed together. Once he was out of their apartment Emmy had a change of heart. Due to the legal delays caused by Emmy and her brothers, it would be six more years before the divorce was finalized. During this period Stieglitz and O'Keeffe continued to live together, although she would go off on her own from time to time to create art. Stieglitz used their times apart to concentrate on his photography and promotion of modern art.

O'Keeffe was the muse Stieglitz had always wanted. He photographed O'Keeffe obsessively between 1918 and 1925 in what was the most prolific period in his entire life. During this period he produced more than 350 mounted prints of O'Keeffe that portrayed a wide range of her character, moods and beauty. He shot many close-up studies of parts of her body, especially her hands either isolated by themselves or near her face or hair. O'Keeffe biographer

Roxanna Robinson states that her

"personality was crucial to these photographs; it was this, as much as her body, that Stieglitz was recording."

In 1920, Stieglitz was invited by

Mitchell Kennerly of the Anderson Galleries in New York to put together a major exhibition of his photographs. In early 1921, he hung the first one-man exhibit of his photographs since 1913. Of the 146 prints he put on view, only 17 had been seen before. Forty-six were of O'Keeffe, including many nudes, but she was not identified as the model on any of the prints.

In 1922, Stieglitz organized a large show of

John Marin's paintings and etching at the Anderson Galleries, followed by a huge auction of nearly two hundred paintings by more than forty American artists, including O'Keeffe. Energized by this activity, he began one of his most creative and unusual undertakings – photographing a series of cloud studies simply for their form and beauty. He said:

"I wanted to photograph clouds to find out what I had learned in forty years about photography. Through clouds to put down my philosophy of life – to show that (the success of) my photographs (was) not due to subject matter – not to special trees or faces, or interiors, to special privileges – clouds were there for everyone…"

By late summer he had created a series he called

"Music – A Sequence of Ten Cloud Photographs". Over the next twelve years he would take hundreds of photographs of clouds without any reference points of location or direction. These are generally recognized as the first intentionally abstract photographs, and they remain some of his most powerful photographs. He would come refer to these photographs as

Equivalents.

Stieglitz's mother Hedwig died in November 1922, and as he did with his father he buried his grief in his work. He spent time with

Paul Strand and his new wife Rebecca (Beck), reviewed the work of another newcomer named

Edward Weston and began organizing a new show of O'Keeffe's work. Her show opened in early 1923, and Stieglitz spent much of the spring marketing her work. Eventually, twenty of her paintings sold for more than $3,000. In the summer, O'Keeffe once again took off for the seclusion of the Southwest, and for a while Stieglitz was alone with

Beck Strand at Lake George. He took a series of nude photos of her, and soon he became infatuated with her. They had a brief physical affair before O'Keeffe returned in the fall. O'Keeffe could tell what had happened, but since she did not see Stieglitz's new lover as a serious threat to their relationship she let things pass. Six years later she would have her own affair with Beck Strand in New Mexico.

In 1924, Stieglitz's divorce was finally approved by a judge, and within four months he and O'Keeffe married in a small, private ceremony at Marin's house. They went home without a reception or honeymoon. O'Keeffe said later that they married in order to help soothe the troubles of Stieglitz's daughter Kitty, who at that time was being treated in a sanatorium for depression and hallucinations. For the rest of their lives together, their relationship was, as biographer Benita Eisler characterized it,

"a collusion ... a system of deals and trade-offs, tacitly agreed to and carried out, for the most part, without the exchange of a word. Preferring avoidance to confrontation on most issues, O'Keeffe was the principal agent of collusion in their union."

In the coming years O'Keeffe would spend much of her time painting in New Mexico, while Stieglitz rarely left New York except for summers at his father's family estate in Lake George in the Adirondacks, his favorite vacation place. O'Keeffe later said

"Stieglitz was a hypochondriac and couldn't be more than 50 miles from a doctor."

The great geniuses are those who have kept their childlike spirit and have added to it breadth of vision and experience. -- Alfred Stieglitz

At the end of 1924, Stieglitz donated 27 photographs to the Boston

Museum of Fine Arts. It was the first time a major museum included photographs in its permanent collection. In the same year he was awarded the Royal Photographic Society's Progress Medal for advancing photography and received an Honorary Fellowship of the Society.

In 1925, Stieglitz was invited by the Anderson Galleries to put together one of the largest exhibitions of American art, entitled

Alfred Stieglitz Presents Seven Americans: 159 Paintings, Photographs, and Things, Recent and Never Before Publicly Shown by Arthur G. Dove, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, Charles Demuth, Paul Strand, Georgia O'Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz. Only one small painting by O'Keeffe was sold during the three-week exhibit.

Soon after, Stieglitz was offered the continued use of one of the rooms at the Anderson Galleries, which he used for a series of exhibitions by some of the same artists in the

Seven Americans show. In December 1925, he opened his new gallery,

The Intimate Gallery, which he nicknamed

The Room because of its small size. Over the next four years, he put together sixteen shows of works by Marin, Dove, Hartley, O'Keeffe and Strand, along with individual exhibits by

Gaston Lachaise,

Oscar Bluemner and

Francis Picabia. During this time, Stieglitz cultivated a relationship with influential new art collector

Duncan Phillips, who purchased several works through

The Intimate Gallery.

In 1927, Stieglitz became infatuated with the 22-year-old

Dorothy Norman, who was then volunteering at the gallery, and they fell in love. Norman was married and had a child, but she came to the gallery almost every day.

O'Keeffe accepted an offer by

Mabel Dodge to go to New Mexico for the summer. Stieglitz took advantage of her time away to begin photographing Norman, and he began teaching her the technical aspects of printing as well. When Norman had a second child, she was absent from the gallery for about two months before returning on a regular basis. Within a short time, they became lovers, but even after their physical affair diminished a few years later, they continued to work together whenever O'Keeffe was not around until Stieglitz died in 1946.

In early 1929, Stieglitz was told that the building that housed

The Room would be torn down later in the year. After a final show of Demuth's work in May, he retreated to Lake George for the summer, exhausted and depressed. The Strands raised nearly sixteen thousand dollars for a new gallery for Stieglitz, who reacted harshly, saying it was time for

"young ones" to do some of the work he had been shouldering for so many years. Although Stieglitz eventually apologized and accepted their generosity, the incident marked the beginning of the end of their long and close relationship.

In the late fall, Stieglitz returned to New York. On December 15, two weeks before his sixty-fifth birthday, he opened

An American Place, the largest gallery he had ever managed. It had the first darkroom he had ever had in the city. Previously, he had borrowed other darkrooms or worked only when he was at Lake George. He continued showing group or individual shows of his friends Marin, Demuth, Hartley, Dove and Strand for the next sixteen years. O'Keeffe received at least one major exhibition each year. He fiercely controlled access to her works and incessantly promoted her even when critics gave her less than favorable reviews. Often during this time, they would only see each other during the summer, when it was too hot in her New Mexico home, but they wrote to each other almost weekly with the fervor of soul mates.

In 1932, Stieglitz mounted a forty-year retrospective of 127 of his works at

The Place. He included all of his most famous photographs, but he also purposely chose to include recent photos of O'Keeffe, who, because of her years in the Southwest sun, looked older than her forty-five years, in comparison to Stieglitz's portraits of his young lover Norman. It was one of the few times he acted spitefully to O'Keeffe in public, and it might have been as a result of their increasingly intense arguments in private about his control over her art.

Later that year, he mounted a show of O'Keeffe's works next to some amateurish paintings on glass by

Becky Strand. He did not publish a catalog of the show, which the Strands took as an insult. Paul Strand never forgave Stieglitz for that. He said,

"The day I walked into the Photo-Secession 291 [sic] in 1907 was a great moment in my life… but the day I walked out of An American Place in 1932 was not less good. It was fresh air and personal liberation from something that had become, for me at least, second-rate, corrupt and meaningless."

In 1936, Stieglitz returned briefly to his photographic roots by mounting one of the first exhibitions of photos by

Ansel Adams in New York City. The show was successful and David McAlpin bought eight Adams photos. He also put on one of the first shows of Eliot Porter's work two years later. Stieglitz, considered the

"godfather of modern photography", encouraged

Todd Webb to develop his own style and immerse himself in the medium.

The next year, the Cleveland Museum of Art mounted the first major exhibition of Stieglitz's work outside of his own galleries. In the course of making sure that each print was perfect, he worked himself into exhaustion. O'Keeffe spent most of that year in New Mexico.

In early 1938, Stieglitz suffered a serious heart attack, one of six coronary or angina attacks that would strike him over the next eight years, each of which left him increasingly weakened. During his absences, Dorothy Norman managed the gallery. O'Keeffe remained in her Southwest home from spring to fall of this period.

In the summer of 1946, Stieglitz suffered a fatal stroke and went into a coma. O'Keeffe returned to New York and found Dorothy Norman was in his hospital room. She left and O'Keeffe was with him when he died. According to his wishes, a simple funeral was attended by twenty of his closest friends and family members. Stieglitz was cremated, and, with his niece

Elizabeth Davidson, O'Keeffe took his ashes to Lake George and

"put him where he could hear the water." The day after the funeral, O'Keeffe took control of

An American Place.

Source: Wikipedia

Image:All images © Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, The Alfred Stieglitz Collection, Gift of Georgia O'Keeffe