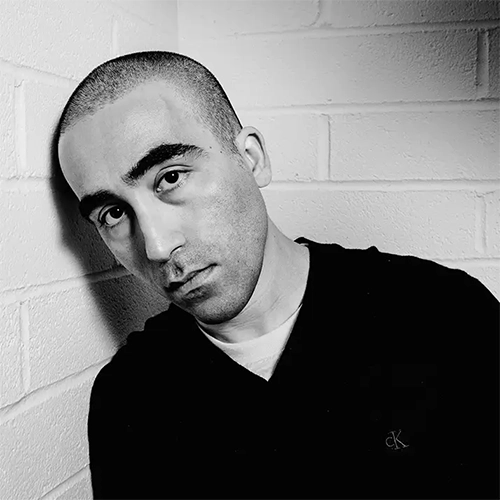

American photographer

Ghawam Kouchaki brings a sharply observant and introspective gaze to the streets of Japan’s capital. Based in Los Angeles, he approaches Tokyo with the distance — and curiosity — of an outsider, allowing him to uncover the city’s subtle contradictions, quiet tensions, and fleeting gestures that often go unnoticed.

His series

Tokyo No-No, selected as the

Solo Exhibition for December 2024, explores the hidden undercurrents of urban life: the unspoken rules, the small ruptures in routine, the poetic strangeness found in everyday moments. Through muted tones, instinctive timing, and meticulous framing, Kouchaki reveals a Tokyo that exists somewhere between reality and imagination — both intimate and enigmatic.

We asked him a few questions about his life and work.

All About Photo: You began your creative path as a filmmaker before moving into photography. How has your background in cinema shaped the way you approach still images?

Ghawam Kouchaki: One of my biggest issues as a director was my lack of a cinematic voice — the ability to visualize a story through images. Photography grew out of that desire to tell a story visually.

When you create a photobook, it can be like editing a film. Putting two images next to each other creates meaning in the same way Eisenstein theorized with montage. You could say every photobook is a film in its purest form because it relies on the viewer to interact with the images and give them meaning.

Photography still ties me back to my filmmaking roots, so in a way, I’m still connected even though filmmaking isn't my path right now.

You’ve cited filmmakers like Edward Yang, Kieslowski, Michael Mann, and Toshiaki Toyoda as influences. What elements of their work resonate with you most in your own visual storytelling?

They all influence me in some way, but I think back to what Tarkovsky said about his influences: “I’d rather not imitate any of them. The main goal of any art is to find a personal means of expression — a language with which to express what’s inside of you.”

All of them have articulated feelings I’ve had throughout my life, the same way a book can connect with how you see the world. They share similarities in style and themes, but they all give voice to the feelings we have toward the state of modern life.

Your photography has been exhibited in both Tokyo and Los Angeles. How have these two very different cultural contexts influenced your perspective as an artist?

Both helped me realize my perspective as an outsider — not feeling like I belong fully in Los Angeles or in Tokyo. Los Angeles has a lot of fake people who use one another to climb the social ladder for fame, which has become a kind of currency in the social-media era.

Tokyo has more of a sense of community, but at the same time I felt alienated there too, because I was a foreigner. Everyone was in their own bubble; culturally there isn’t much chance to meet someone new on the street or in a line somewhere. Encounters happen, but they’re rare.

In both cities, when your value as a person is tied to who or what you are, you feel invisible. Sometimes that can be beneficial — especially as an artist, because you can melt into the background and watch society present itself.

Wim Wenders is an example I look to: when he made “American” films, they were interesting because his outsider perspective helped him see America more clearly than those who grew up surrounded by it.

What first drew you to Tokyo as the setting for this project?

I had the opportunity to come to Tokyo for a month and wanted to create a book. If you can travel outside of your station, you should take it — especially as an artist trying to expand your horizons.

I didn’t have a singular idea, but I knew I wanted to contain it to Tokyo. I followed my instincts and the scenes that attracted me in the first week.

This was my third time visiting Japan, and I noticed things that reminded me of both America and Iran.

You describe Tokyo No-No as examining modern alienation through the family unit. Can you share how this theme emerged during your time in Japan?

It came from the scenes I encountered — a wide range of subjects across different ages that I reacted to and captured. The idea didn’t fully come together until another photographer, Eduardo Acosta, pointed out in my editing and sequencing that I could divide the work into chapters from young to old.

Hustle culture and relentless movement are central to the narrative. How did you personally experience this energy while photographing the city?

I saw similarities to the US — people constantly on their phones, either showing their daily lives or trying to maximize time to make ends meet.

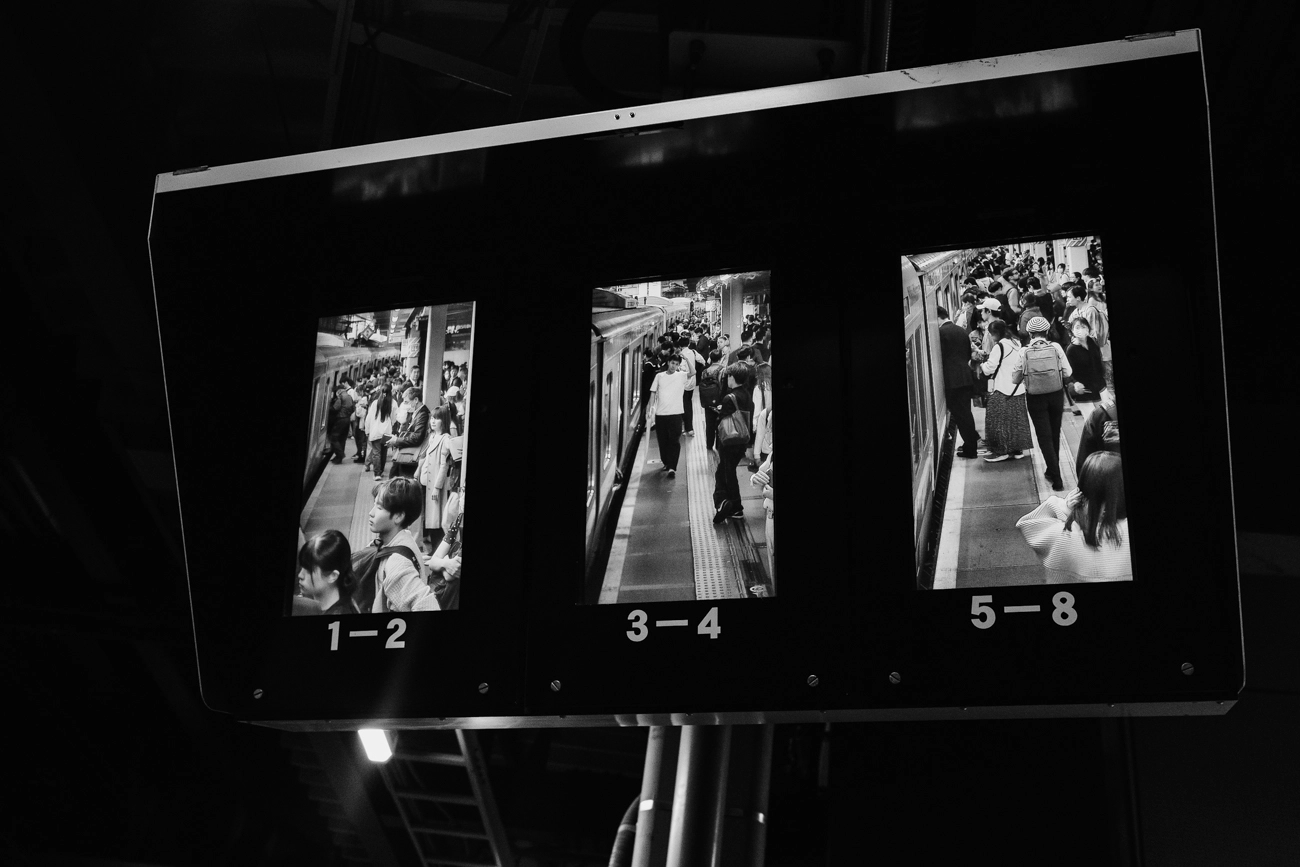

Salarymen spent their lunch breaks multitasking, eating while watching content to make the grind more tolerable. People on morning trains took power naps because they pulled all-nighters for their companies. Delivery drivers bounced from restaurant to restaurant fulfilling UberEats orders like in downtown LA.

It felt like most people were living life with their finger on the fast-forward button, always trying to use their time efficiently. But when they were still — at meals or on trains — they’d turn to their phones to play games, read, or watch someone living the life they wanted.

Modern life has created different flavors of the same problem: people can’t imagine a future for themselves because they’re struggling just to get through each day.

You’ve said that even though these themes aren’t unique to Tokyo, something about the city’s atmosphere amplified them. Could you elaborate on what made Tokyo stand out?

People I talked to in Tokyo said the same. Some parts of the city feel claustrophobic — everyone crammed together like rush hour on the metro. When contact is that close, you notice how far away people seem psychologically.

Everyone has their part to play, so individuality isn’t emphasized. People can come together and create something good, but it can also rob you of personal identity when you have to be a pillar supporting a hyper-technological society like Tokyo.

I’ve seen similar problems in Iran — people looking miserable on the train. But one thing that connects every country I’ve visited is that some of the youth are the only ones who seem to have genuine smiles and enjoyment in life.

You often get up close and personal with your subjects. How do you navigate capturing such raw, intimate moments in public spaces?

Sometimes I just do it; sometimes I ask. It depends on the situation and what I’m trying to show. It’s harder for people to look away from a very close photo — it lets you really see someone.

A lot of photographers are afraid to get close. It’s the old Robert Capa quote: “If your photos aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.”

The camera, especially the flash, seems to wake people up from this autopilot they're on and reveal themselves.

Was there a particular image in the series that crystallized the project for you—where you thought, “this is the essence of Tokyo No-No”?

Probably the one image I can think of right now is of a man, woman, and child I photographed on my second to last day at a stop on a train to Akihabara. This woman had dozed off in the train, while this man sitting at the other end of the seat was staring at his phone, and in the background a child in a carriage passed by the window and looked at me. For a brief second I saw a sort of family, but they were all disconnected, all separated by one thing or another.

How do you balance instinct with intention when shooting—are you planning shots or responding entirely to the moment?

Most of what I shot was instinct. Some shots I tried to compose, but shooting without thinking made it easier to capture moments. Now, I work some scenes from multiple angles or wait for something to unfold, something I learned from Moises Saman and my classmates at the Fuji x Magnum Photo Workshop in Seoul.

The work touches on universal struggles: economic instability, broken expectations, loneliness. Did working on this project also change how you reflect on your own life in Los Angeles?

Not really. There are times when I’m lucky to get certain gigs friends recommend me for, and I’m extremely lucky to make some money doing photography, even if it’s not very much. It’s the nature of art right now — every artist struggles to make a living because the successful artists are increasingly being those who come from money rather than their art. Rich artists can afford to not work and focus on their art unlike most people who don't have the same access as they do or the resources to make their art.

You mention that the energy of your subjects reflected your own feelings back at you. What emotions do you hope viewers will see reflected in themselves?

I hope that, like other photographers have talked about, someone stops on one image and for a brief second it affects them enough to try to implement a small change in their life. I don’t know if I can evoke emotions with my images, but I hope one photo can make someone feel less alone and articulate a feeling they have about the world that they couldn’t describe in words.

In many of your images, people appear at a breaking point. Do you see your photography as a form of social critique, or more as a mirror for personal reflection?

I don’t really think of it that way. If I capture someone at their breaking point, it’s not because I think it’s a critique of society. I grab it because in that moment I’ve felt those same emotions, but it’s more instinctual when I capture it.

You’re currently working on a photobook of Tokyo No-No. What do you hope readers will take away from experiencing the work in book form rather than in an exhibition?

I hope the book can reach people beyond borders and across generations. I hope the same feelings I reacted to while making it can help someone articulate their own thoughts through images they connect with.

Do you see yourself returning to Japan—or exploring other cities—through the same lens of alienation and resilience?

Hokkaido has been on my mind a lot, but that’s a different project and subject matter.

I’d like to continue a series I started in 2016, but people have become very sensitive to having their picture taken since then, so I have to get creative with this project.

What role do you feel photography can play in helping people pause, reflect, and maybe even shift the course of their lives?

Like others have said, if you can stop someone even for a second with one of your photos, that counts as a shift in their life. Any amount of change, even a second of reflection, can affect someone — especially when they can recall an image that sticks in their mind.

Anything else you would like to add?

You’re a human being first before you’re a photographer.

Influencers are not photographers.

POV street photography videos are ruining photography because you take away the audience’s participation in the image when you show them how it was made. It’s like revealing a magician’s tricks — you remove the guesswork, and the work becomes dead because you’ve answered the question instead of leaving them with one.

Most of these youtube photographers who make videos about photographers aren't bringing anything new to the conversation about these photographer's work, they're just reading off wikipedia summaries.

Film doesn’t make your photography better.

Influencers have ruined photography.

PRINT YOUR PHOTOS.

Most modern editorials shot on film are awful. Editorials in general have become lazy, where you have a photographer shoot their subject in a parking lot or hotel room. How do these photos tell me who this subject is? Why are you shooting everything with the shallowest depth of field? Stop hiring influencers to shoot your commercial campaigns or editorials, they are awful.

No one wants to make art — they just want to call themselves artists without putting themselves on the line.

It’s range-focusing, not zone-focusing.

There should be no more videos of people loading films into their cameras. It's stupid.

Get out of your comfort zone and try new things, you never know what you will see.

Shoot more photos instead of making videos. You can't take good pictures when you're trying to make a video, you will miss those decisive moments because you're trying to farm engagement for the algorithm.

Success is the worst thing that can happen to a young photographer.

Never succeed until you’re 43.

Twenty-two year olds shouldn't be teaching photo workshops. Photographers should have 20 years under their belt before they start offering to lead photo workshops.

Keep failing.

PRINT YOUR PHOTOS.

Get your stuff seen by other people, it doesn't need to be in a gallery or on social media. Be creative in how you get your work out there amongst the noise.

Camera companies should stop appealing to influencers to boost sales, because they don’t care about art — especially photography. They care only about fame. They’ll sell the camera they were given for free at an event a month later on eBay or Facebook Marketplace. Instead those companies should donate those cameras to schools to give access to students who want to create art.

We need to support each other more and stop being mavericks; a community will help photography thrive, not cliques.

It's okay to take a break from photography, it'll make you a better artist and person in the long-run.

MIND YOUR BACKGROUNDS.

GET CLOSE.

STUDY HISTORY.

PRINT YOUR PHOTOS.