CRAIG VARJABEDIAN'S photographs of the American West illuminate his profound connection with the region and its people. His finely detailed images shine with an authenticity that reveals the ties between identity, place, and the act of perceiving. For Varjabedian, photography is a receptive process driven by openness to the revelation each subject offers, rather than by the desire to manipulate form or to catalog detail. He achieves this vision by capturing and suspending on film those decisive moments in which the elements and the spirit of a moment come together.

Craig is also funny. Not mean-funny, or foul-mouthed funny, and it's never at your expense. It's a wholesome, vaguely Canadian, quietly-sly funny where he'll cut his eyes over at you and burst out with a HA! and you realize why photography students return from all across the country to his workshops. The education is top-notch: a masterful blend of hands-on attention and letting you get into your own kind of creative trouble, but learning from and listening to Craig himself is a highlight of the experience.

Craig's conversation style is suited for long car rides to scenic destinations, the vehicle full of workshop students feeling their way around getting to know each other, talking and sharing stories as the miles pass. This interview took place during the COVID-19 pandemic and those days are in the rear-view mirror for now, but I'm hoping to be on the road with him again soon.

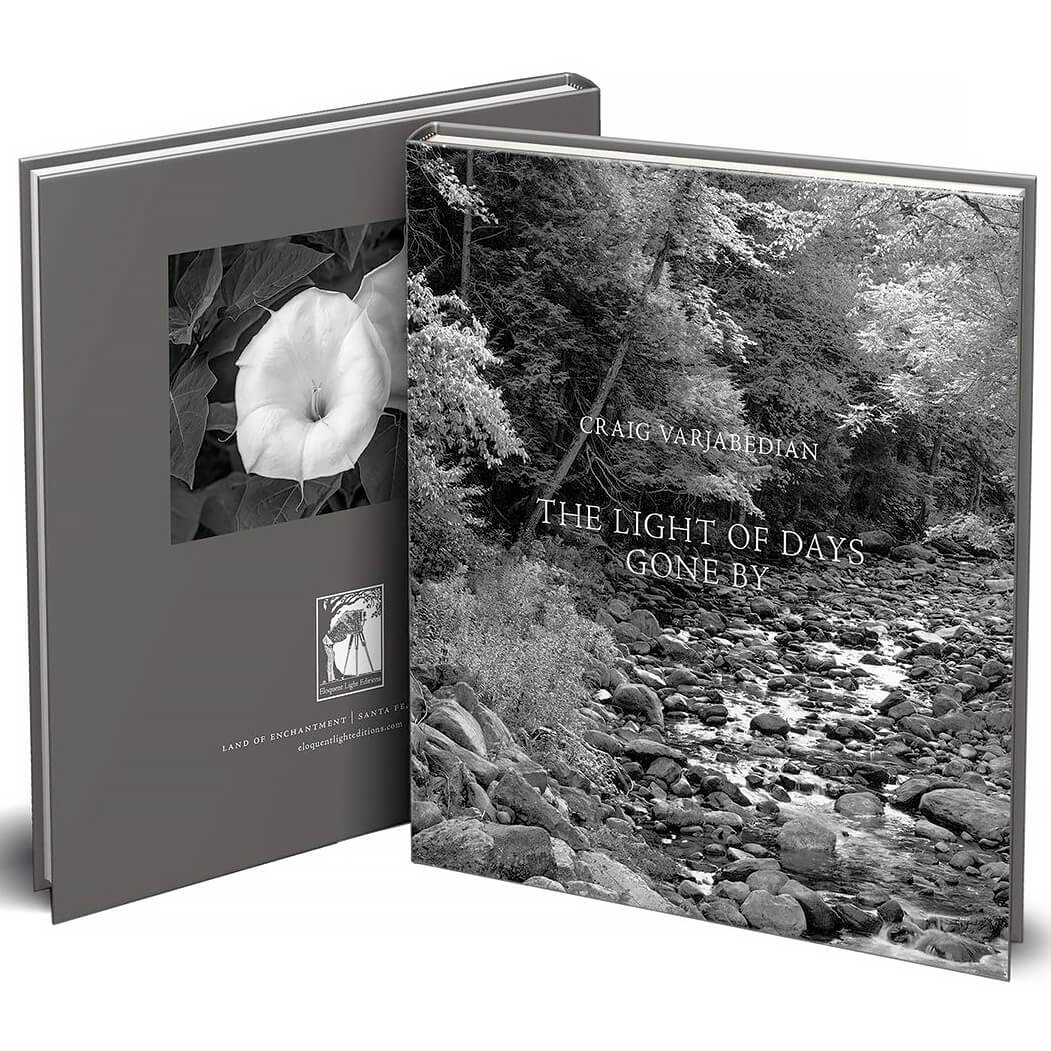

I was lucky enough to spend three and a half hours on the phone with Craig, for a wide-ranging interview about his new photography book, The Light of Days Gone By, which spans 45 years of his work. This interview has been condensed, and edited for clarity.

Nudahunga, Omaha Native American Powwow Dancer, Summer, San Marcos, New Mexico © Craig Varjabedian

I photograph because I have to, it's my way of connecting with the world. It is a search for meaning and an attempt to connect with something much larger and maybe even more lasting. Being able to make pictures is a tremendous gift, and I can't imagine what my life would be without it.

I'm always seeking, hoping to receive a glimpse of the truth in whatever form that is. There's a part of me that hopes to never find an absolute truth, because the search itself is the gift and it brings me such joy. I've always had this insatiable desire to learn, because I want to deeply grow as a human being. I have this feeling that if I make another picture, I'll get closer to that something that keeps calling me to make pictures. It's very purpose-driven. I can't even imagine what my life would be like if I didn't do this.

It's part of the thing that gets me up in the morning, the possibility that I could make another picture. That the experience starts to approach something miraculous. I sense that there's this large piece still missing in my wholeness, so I make pictures as a way of trying to find that completeness. It's the opportunity of possibly making a profound connection with the world and whatever it is I'm trying to photograph.

I use photography as part of my practice. It's a desire to connect with something greater than myself, something even greater than mankind. I see it out on the plains of White Sands. I see it in the hills of Ghost Ranch. I see it in the faces of people I've photographed. I thank my lucky stars this path called to me as loudly as it did 45 years ago. I'm astonished that I'm able to do this as my life, and I'm astonished at the generosity and support of others.

Blossoms of the Sacred Datura, Summer, Santa Fe, New Mexico © Craig Varjabedian

When I worked commercially at the beginning of my career, I was shooting all kinds of things. Anything from a corporate headshot to a plumbing part. It wasn't terribly satisfying, but it paid the piper. When we moved to Santa Fe and I started working on my own, I found my joy again and began photographing the things I fell in love with. Things that were beautiful, and authentic. I photographed the Penitente Brotherhood, I photographed Ghost Ranch, I photographed White Sands. And I began the Native American project because I was intrigued to understand them better. The thing I've walked away with understanding is that when I made the shift from having clients to service to being my own client, making pictures became a lot more satisfying and more enjoyable.

Black Tree and Orphan Mesa, Summer, Ghost Ranch, New Mexico © Craig Varjabedian

How I come to choose a certain subject is really driven by wanting to learn about it; to better understand its subtleties, its nuance and perhaps even its beauty. I took on the White Sands project because I wanted to learn more about that place. And I don't mean how many square miles, what's it made out of...That's the obvious. I wanted to know what it's like to be White Sands. That's how all these projects make sense to me. One of the greatest experiences I've ever had at White Sands National Park (and I'm not sure I've ever told this to anyone else) is the time I laid down on the ground, and rolled down one of the gleaming white dunes. I just relaxed into it, it was a great experience. Certainly I had sand in my teeth and hair afterwards, but it was worth the tumble, just once. I wanted to make physical contact with this land that I wanted to explore and understand, and that was a way to do it. And it was fun.

When I photograph, it's one of the most joyous experiences of my life. I come home at the end of the day feeling terribly satisfied and spent. Even if I didn't come back with the masterpiece, I feel like I moved a step closer to possibly achieving it. I have told my daughter, Rebekkah, that the goal in life is to move one inch every day towards becoming your better self. Even if I didn't come back with the masterpiece, I moved my inch. And I learned things that will serve me in making a future photograph and who knows what else.

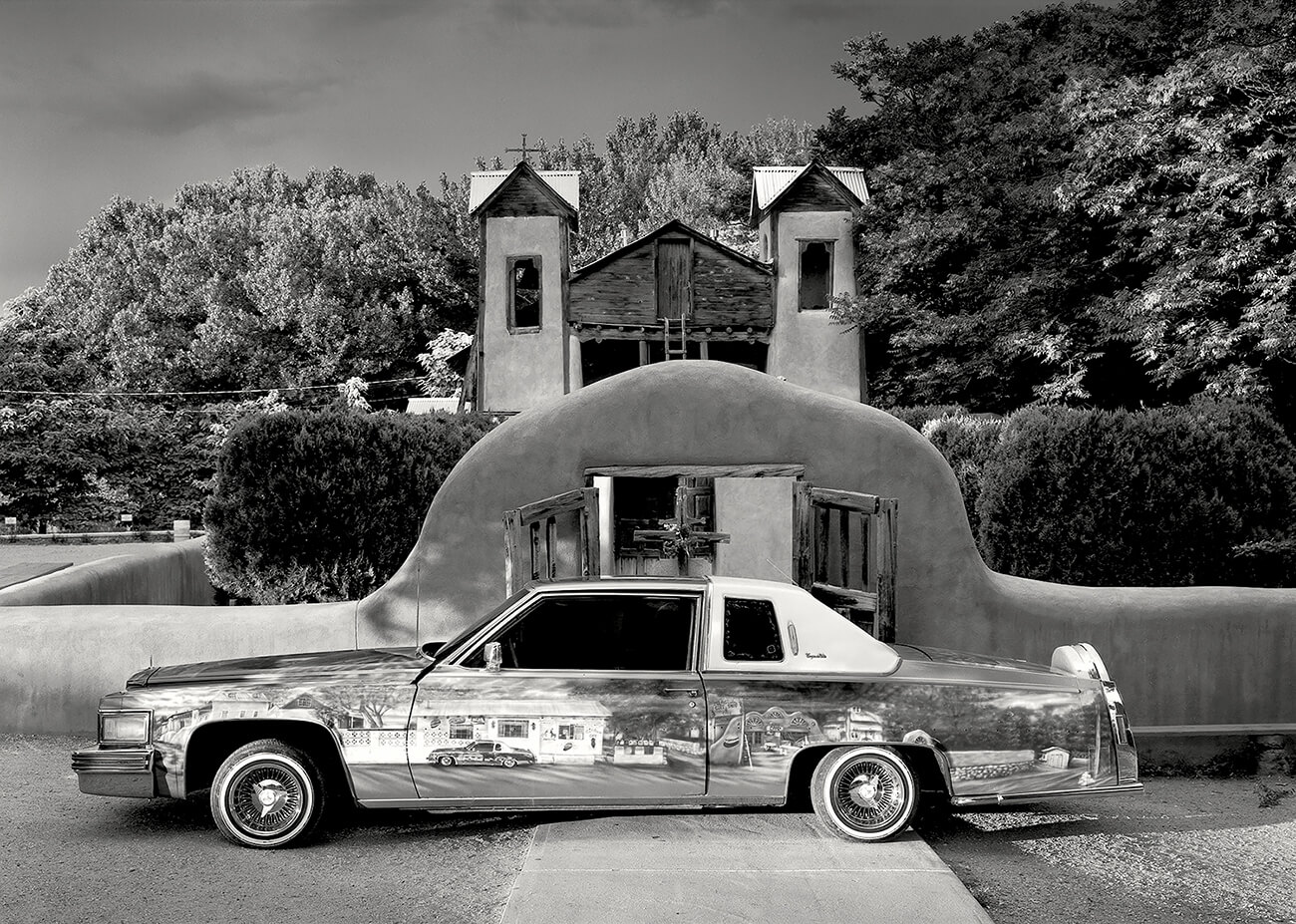

Lowrider Cadillac named Chimayo, Santuario de Chimayó, Chimayó, New Mexico © Craig Varjabedian

When you get on a diet of thoughtfully looking at photographs, you become really aware of the nuance of visual imagery. You learn how putting a frame around a subject changes it in some way. In a good photograph, you begin to understand why things were included, why something was cropped a certain way, why the main subject(s) were placed in a specific location in the frame and so much more. By going on a diet of looking at images, you build a kind of facility of being able to understand how images are constructed. It's like drinking good wine: you might like red or you might like white. Perhaps a rich pinot noir or an oaky chardonnay is more to your liking. After you drink wine for a while, you begin to discover the subtlety of what you have in your glass and what you like and don't like. And this will probably change over time. When truly studying photographs, you internalize more than just the rules of composition. Everything builds on what we know. You begin to recognize how photographers best reveal their subjects and how images may elicit an emotion. You begin to discover and are able to articulate why you like or don't like an image. And this, too, will change over time.

When I'm looking at photographs, one of the other things I'm looking for is evidence of a mind at work. I'm looking for something with complexity, I'm looking for paradox. I think a great picture doesn't answer everything, that there's room for you as the viewer to join the photographer. If someone takes a picture that tells me everything, then great, thanks, I'm moving on. There's no reason for me to linger because I've taken it all in, I understand everything.

Archie West and his Pal Buddy, San Marcos, New Mexico © Craig Varjabedian

The Ansel Adams workshop I took years ago was such a life-changing experience, it was enjoyable beyond words. I believe it was Ansel's sense of wanting to have fun at the service of making photographs that was contagious. I often heard him laughing nearby when we were out photographing. And he knew his stuff, being able to explain the subtle nuances of photography when needed. I've always tried to incorporate a sense of that experience into the workshops I teach. Making photographs should be enjoyable. I teach because I think it's important to give back (and I know that sounds a little bit corny). Photography has given me so much, and I want to share my joy in it. My adopted uncle Paul, a Presbyterian minister in Montana, chose to share the Word not by quoting bible verses, but by action and the way he chose to live his life. Paul would call this photographing, teaching, creating, publishing, exhibiting thing I do—a ministry. It certainly feels like a calling.

When I'm teaching a workshop, it's not about what I personally like and dislike in an image. It's about helping students find their way. It's about acknowledging and supporting others to love the things they're photographing, and to listen carefully to what they're saying about their pictures. I work to act like a mirror and reflect back to them what I see in their pictures vs. what they are telling me about them. I work to wed the student's intent for a picture with what they show me.

Under a Crescent Moon, September 26, White Sands National Park, New Mexico © Craig Varjabedian

I don't believe my overall style has changed but equipment and materials do allow the photographer to explore new paths. The biggest gift that digital photography has brought to my work is the ability to explore and reliably control color in my work. However if you were to ask me if I see the world differently with a film camera vs. a digital camera, I probably would say no.

I wish my wet darkroom was up and running right now, I have an idea I would like to explore with those tools and materials. Current circumstances have required me to work digitally and that's quite fine. While film-based photography and digital photography will both yield an image, the subtleties of each are vast. When I am creating an image, I want to explore and even exploit those subtleties to be able to fully express what I want to say about what I am photographing. I choose the tools and materials to this end. People are so often looking for absolutes here, and will choose sides.

Film is better.

Digital is better.

Nikon is better.

No, Canon is!

And on and on and on. For me photography is art and art is ambiguous. We have to employ all the tools at our disposal to fully express that which may be inexpressible. It's a bit like the difference between watercolor and oil painting—you can paint a landscape with either of those materials, but you will get two very different landscapes. The sense of feeling is very different in the watercolor vs. the oil: it's not a suggestion that one is better than the other, but the mediums are chosen, hopefully, because the artist wants to express and even reveal something specific about what they are painting.

For instance, when I started the White Sands work, I was going to do that project in black and white. But I found out that there was so much color I was leaving on the table, it bothered me. I thought about switching to color film, but the problem is that I didn't have a way reliably to work with those materials. I was always at the mercy of the film and the photographic paper and the photo lab I would invariably have to use to make the prints. Also, in the case of my view camera, which is relatively heavy, it became logistically difficult to move it around that sand-covered landscape. And sometimes beautiful and magical moments at White Sands happen pretty quickly. I decided to switch to a digital camera because it was the best tool to use to achieve the images I wanted to make. In the end, the final image determines the tools I use, not the other way around.

Illuminated Stream, Dawn, Plymouth, Vermont © Craig Varjabedian

It's easy to get lost in the allure of fine camera gear. Believe me, I've done it. Years ago, I came to know this old photographer named Frank who told me that when he started out making pictures in the early part of the last century, he had one camera and one lens and he shot lots of pictures. Shortly thereafter, as his bank account grew, he acquired another lens and another camera. Then another lens. Then another one after that. After a while he had accumulated a bushel-full of lenses and suitcase-full of cameras and eventually discovered that as he acquired more and more cameras and lenses he made fewer and fewer pictures. Aahhhhh!

Listen folks, unless you're a camera collector, photography is about a profound response one has to life. We record those moments to understand, to remember, to savor and to share them. With that said and for what it's worth, the following is what I typically carry:

Gura Gear Kiboko 22-liter pack

Nikon D850 Camera

NIKON AF-S NIKKOR 24-70mm f/2.8E ED VR

NIKON AF-S NIKKOR 14-24mm F2.8G ED

NIKON AF-S NIKKOR 70-200mm f/2.8E FL ED VR

Nikon Circular Polarizer II Filter

Really Right Stuff TVC-24L Tripod with BH-40 Ballhead

Sometimes specific items are added depending on what I am photographing, like a water bottle, protein bars and a GPS while in the field or a NIKON AF-S NIKKOR 105mm f/1.4E ED or a Nikon AF-S NIKKOR 200mm f/2G ED VR II Lens if I know I will be making portraits.

Red Sky and Dunes, Sunset, Autumn, White Sands National Park, New Mexico © Craig Varjabedian

For me, making images has been part of a long continuum. Every image brings me a little bit closer and a little bit clearer to that something, but as yet I am unable to see the whole picture. I don't really have a map, I just know it's somewhere over the next horizon. Places call. I never knew, when I look back over my previous projects, that I'd go from making pictures of Penitente Moradas to photographing the windswept landscape of Ghost Ranch. If you'd asked me back in the ‘80s if I'd seen the Ghost Ranch pictures on the horizon, I probably would have said no. I had to wait ‘til I arrived at that next horizon to glimpse it. There's been a lot of horizons. The latest movement into the Native American images has been my most recent shift in work, and if my past is any indication, I'll get to the end of this and another horizon will assuredly appear. My pictures and themes eventually find me. I don't know what's over that next horizon, and there's a piece of me that loves that.

In terms of dreams, there are so many places I hope I have a chance to see and photograph because I would love to know about them, and I sense they have something to teach me. Right now, Greenland and the Faroe Islands are two places that are strongly beckoning me to go there. I don't know what the future holds. The force is strong...

My new book

The Light of Days Gone By, while definitely highlighting 45 years of image making, is only a glimpse. There were so many images I wished we could have included, and my studio director Cindy Lane and I went around and around for weeks trying to choose. The book is just a resting point, to consider and reflect. It was published to mark this important occasion. My time behind the camera is far from over. I'm always interested in that next photograph, that next horizon to sail towards, that new image I will make when I get there.

About Brody Q. Scotland

Brody Q. Scotland is an enthusiast and a friend to all creatures great and small. Her photographic work has appeared in The Sun magazine.

Chuugaa hoewii (Redhawk), Tewa, Ohkay Owingeh © Craig Varjabedian

Yanabah Moonsky (Sky warrior), Diné © Craig Varjabedian