Global climate change is evident and has noticeable effects on the environment. It affects all regions of the world. The polar ice caps are melting and the level of the oceans is rising. In some regions, extreme weather events and precipitation are becoming more frequent, while others are facing increasingly extreme heat waves and droughts.

Many plants and animal species are endangered. Some terrestrial, freshwater and marine species have already moved to new territories. Plants and animals will be in serious danger of extinction if the average temperature of the planet continues to rise uncontrollably.

These effects are expected to intensify in the coming decades. Scientists agree that global temperatures will continue to rise for decades to come, largely due to greenhouse gases produced by human activities.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which includes more than 1,300 scientists, forecasts a temperature rise of 2.5 to 10 degrees Fahrenheit over the next century.

According to the IPCC, the extent of climate change effects on individual regions will vary over time and with the ability of different societal and environmental systems to mitigate or adapt to change.

With these facts in mind,

All About Photo has selected photographers who are documenting the consequences of climate change on our beautiful planet and its inhabitants.

Thanks to their dedication and courage, we can observe the effects of climate change on all four corners of the world. We believe that their work is key to help climate skeptics open their eyes and minds.

Skepticism is a significant barrier to public engagement when we should all act as one. But if facts and words don't curve their little trust in what they are told, can an image make a difference?

We asked renowned and committed photographers the same simple question:

Do you think that photography can help raise awareness about Climate Change?

Here are their personal and heartfelt answers as well as their astounding images to convey their message.

Nick Brandt

A qualified yes. More and more of us are turning our very necessary urgent attention to showing the impact of climate change.

However, the irrational denial of man-made climate change in certain countries like America and Australia is so fervently ingrained among many, largely thanks to the shameless right-wing press, that I sometimes feel that our audience is made up of those who are already aware and converted.

But that should never ever stop us from doing everything we can to further raise awareness in whatever way we can. Just look at how much just one 17-year-old Swedish girl has achieved in the space of one year.

My previous work - about the disappearance and destruction of the natural world in East Africa- has only tangentially touched upon climate change, but with my next project, about climate change in America, I will be very much addressing it directly. -

Nick Brandt

The themes of

Nick Brandt (British, b. 1964) relate to the disappearing natural world, rapidly changing and vanishing at the hands of mankind.

From 2001 to 2018, he has photographed in Africa. In his celebrated trilogy, On This Earth, A Shadow Falls Across The Ravaged Land (2001-2012), he established a style of portrait photography of animals in the wild similar to that of the photography of humans in studio settings. Shot on medium format film, these series portray animals as sentient creatures not so different from us.

In Inherit the Dust (2016), a series of epic panoramas, Brandt recorded the impact of man in places where animals used to roam but no longer do. In each location, Brandt erected a life-size panel of one of his unreleased animal portrait photographs, placing the displaced animals on sites of explosive urban development, new factories, wastelands, and quarries.

This Empty World (2019) addresses the escalating destruction of the natural world at the hands of humans, showing a world where overwhelmed by runaway development, there is no longer space for animals to survive. Working in color for the first time, in visually complex tableaux populated by both humans and animals, This Empty World is both a technical tour de force of contemporary image-making and an ambitiously scaled project that uses constructed sets on a scale typically seen in major film productions.

Brandt has had solo gallery and museum shows around the world, including New York, London, Berlin, Stockholm, Paris and Los Angeles. Inherit the Dust most recently has been exhibited at Multimedia Museum of Art in Moscow and the National Museum of Finland in Helsinki. Born and raised in England, Brandt now lives in the southern Californian mountains. He is co-founder of

Big Life Foundation, fighting to protect the animals of a large area of Kenya and Tanzania.

Nick Brandt's Website

Nick Brandt on Instagram

All about Nick Brandt

Both animals and humans are victims of environmental degradation and climate change. Environmental degradation will almost always affect poor rural people the most, due to the exhausted natural resources upon which they rely.

(In the photos with the humans and elephants, both were photographed from the exact same camera position, first the (wild) elephants, and then people from the local community in Kenya.)

© Nick Brandt, Courtesy of Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York

This Empty World,, Elephant & Human Family, 2018

© Nick Brandt, Courtesy of Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York

This Empty World, River of People with Elephants in Day, 2018

© Nick Brandt, Courtesy of Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York

This Empty World, Whistling Thorns with Gazelle, 2018

I do have one worry that the imagery we often choose to show the climate emergency is typically showing the most extreme of its effects and that then becomes the stereotype of climate change. Climate change has many faces and they are not all visually dramatic and if we leave out more nuanced and real everyday stories we are yet again avoiding reality. I believe as a photographer it is our responsibility to see deeper and further and listen and look carefully to everyone and everywhere - in reality, once you have started working on climate change it becomes so obvious to you what you are seeing.

Working on a project about climate change for the past 5 years in California has been eye-opening to the changes we are already seeing in the State: you feel the rising temperatures, 149 million trees have died in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, there are larger and more aggressive wildfires and drought is affecting water supply and agriculture.

What has stuck with me more than anything was while documenting the aftermath of the Woosley fire in Malibu CA, a family was going through the burnt-out remains of their home and one of them who is a college professor said ''I always thought climate change would happen to someone else, somewhere over there, not here to my family''

As frustrating and depressing it can be working on the Climate Emergency, I believe it is not my job to try and convince people, it's my job to show reality. -

Mette Lampcov

Mette Lampcov is a freelance documentary photographer from Denmark, based in Los Angeles. She studied fine art in London, England and after moving to the United States 13 years ago.

Her personal work includes projects about gender-based violence and undocumented migrant workers in California. She is currently concentrating on a long term project Water to Dust documenting how climate change is affecting people and the environment around them in California.

Her work has appeared in the New York Times, The Sydney Morning Herald, Open Society Foundation, BuzzFeed News, The Guardian, The Phoblographer

She is a regular contributor to @everydayclimatechange and @everydaycalifornia

Mette Lampcov's Website

Mette Lampcov on Instagram

All about Mette Lampcov

A girl finds her orange bicycle, it survived the wildfire that had raged through the street of her neighborhood where she lived, destroying many homes, in Malibu California.

The Woolsey fire started Nov 8th and burnt 96,949 acres and destroyed more than 1500 structures.

In the last year, California has seen the largest number of fires in succession. These fires are driven and helped by climate change conditions such as extreme heat, ongoing drought, and low humidity high winds, essentially creating the perfect conditions for more aggressive, fast-moving fires. The ferocious heat helps generate its own wind and sparks embers that fly hundred of meters ahead, and the homes that are in the way are just more fuel for the fires to consume and then adding to that, are decades of fire suppression that creates overgrown underbrush and dry vegetation ready to combust.

The aftermath is thousands of people who have lost their homes and all their belongings, memories turned to dust and ashes, with only a few objects that withstand the heat of the fires, that people can salvage. This is what climate change affects looks like, affecting us directly and right now.

A car drives up Latigo Canyon, where the Woolsey fire brunt leaving scorched hills with not vegetation. It is estimated that California's landscape will be forever altered from increasing and more aggressive and hotter wildfires that tress can't survive and much of the landscape will turn into grasslands.

A prescribed fire is reflecting in Shaver Lake California. Since 2014 the Sierra Nevadas has seen unprecedented levels of tree mortality with as many as 149 million trees across 8.9 million acres lost. Where once stood a lush, green forest, there are now trees turning yellow and brown. The alarmingly accelerated pace of their death is linked to the stress caused by climate change, more specifically increased temperatures, years of severe drought, and an unhealthy overgrowth due to years of fire suppression, which led to a significant spike in bark beetle infestations.

Farm laborers are weeding watermelons in the San Joaquin valley, in California. California has had the perfect mediterranean climate for growing fruit, vegetables and nuts and is the single largest producer of food in the United States, with a 7 billion dollar worldwide export industry. Climate change related events affects will include reduced levels of water supplies, heat creating more plant stress and fewer chill hours effecting food security.

The California aqueduct as it flows from the Bay Delta to Southen California through the San Joaquin Valley. California relies on a very fragile water supply, and as temperatures rise there is more demand and less availability.

-

Ragnar Axelsson

For over 40 years,

Ragnar Axelsson, Rax, has been photographing the people, animals, and landscape of the most remote regions of the Arctic, including Iceland, Siberia, and Greenland. In stark black-and-white images, he captures the elemental, human experience of nature at the edge of the liveable world, making visible the extraordinary relationships between the people of the Arctic and their extreme environment – relationships now being altered in profound and complex ways by the unprecedented changes in climate.

A photojournalist at Morgunbladid since 1976, Ragnar has also worked on freelance assignments in Latvia, Lithuania, Mozambique, South Africa, China, and Ukraine. His photographs have been featured in LIFE, Newsweek, Stern, GEO, National Geographic, Time, and Polka, and have been exhibited widely.

Ragnar has published 7 books in various international editions. His most recent, Jökull (Glacier) was published in 2018, with a foreword by Olafur Eliasson. Andlit Nordursins (The Face of The North), was published in 2016, with a foreword by Mary Ellen Mark, and won the 2016 Icelandic Literary Prize for non-fiction.

Other awards for Ragnar's work include numerous Icelandic Photojournalist Awards; The Leica Oskar Barnack Award (Honorable Mention); The Grand Prize, Photo de Mer, Vannes; and Iceland's highest honor, the Order of the Falcon, Knight's Cross.

Ragnar is currently working on a 3-year project documenting people's lives in all 8 countries of the Arctic. At this pivotal time, as climate change irrevocably disrupts the physical and traditional realities of their world, Ragnar is bearing witness to the immediate and direct threat global warming poses to their survival.

Ragnar Axelsson's Website

Ragnar Axelsson on Instagram

All about Ragnar Axelsson

Last Days of the Arctic, Blizzard in Ittoqqortoormiit village on the east coast of Greenland

Last Days of the Arctic, A piteraq storm in the village of Sermiliqaq on the east coast of Greenland

Last Days of the Arctic, Hunter Mikide Kristiansen fixing his dogs on the ice in Thule (Inglefield fjord)

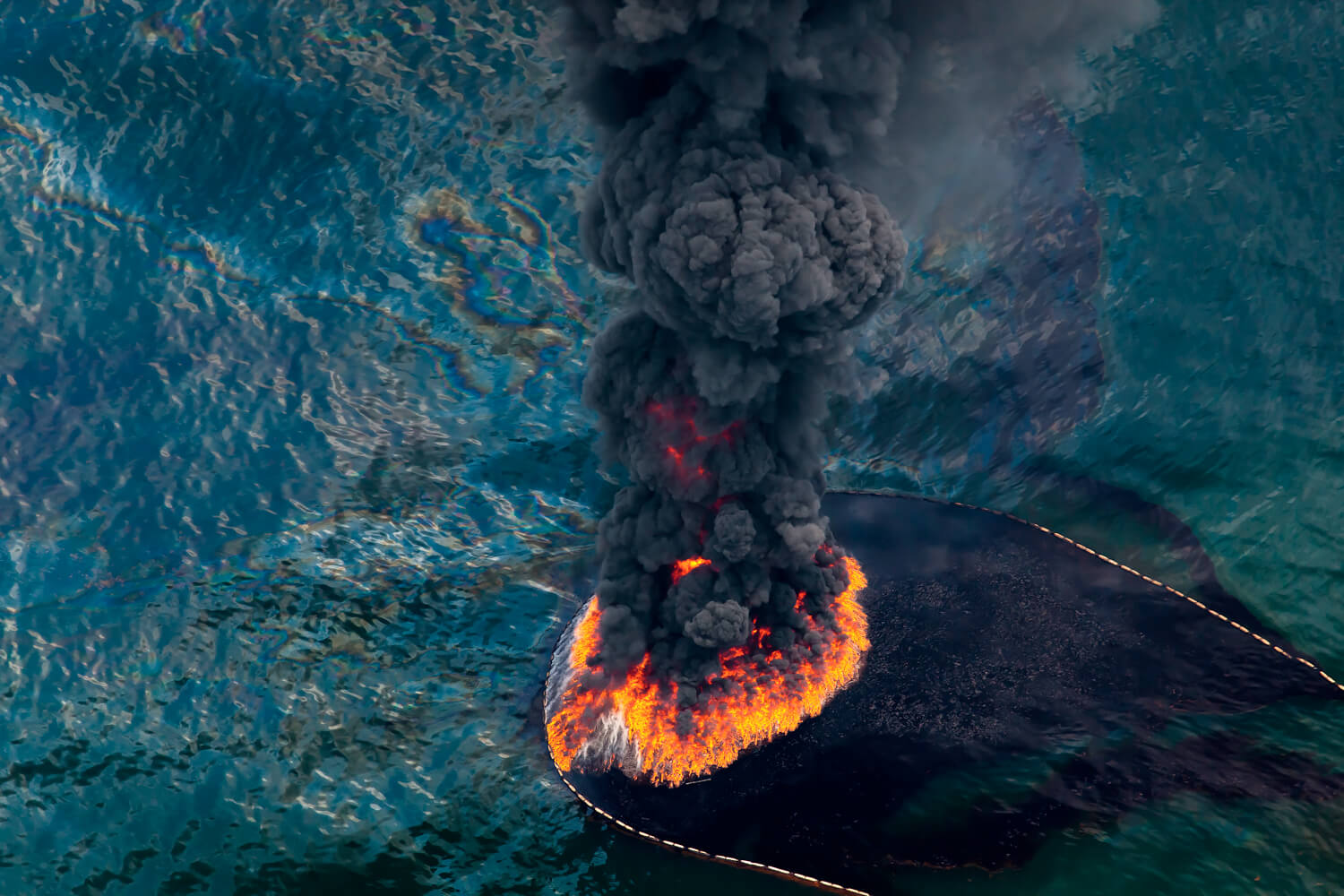

My method for doing this, especially in the past 15-20 years, has been to do this via aerial photography of threatened, and more often it seems now damaged landscapes and ecosystems. The aerial perspective allows me to juxtapose nature with the destruction wrought by an unsustainable appetite for resources, a view that has more empathy and context than that of a satellite. The message that (I hope) these photographs convey is that the Earth and its seemingly endless abundance is, in fact, finite. I think only good things can happen when people see photos and coverage of climate change, gaining a deeper appreciation of nature and the precarious balance our lifestyle has placed upon the planet.

Once people are inspired there is an opportunity for them to take action. This can be done in a variety of ways, but I think most directly it is by voting with both our ballots and our wallets. What nearly everyone wants is for future generations to inherit a world that can sustain life for all, not just those fortunate few. The challenge to accomplish this is getting more people on a more environmentalist and conscientious path. Photography and images of climate change can help get people to take those first steps down that path. -

Daniel Beltrá

Born in Madrid, Spain,

Daniel Beltrá is a photographer based in Seattle, Washington. His passion for conservation is evident in images of our environment that are evocatively poignant. The most striking large-scale photographs by Beltrá are images shot from the air. This perspective gives the viewer a wider context to the beauty and destruction he witnesses, as well as revealing a delicate sense of scale. After two months of photographing the Deepwater Horizon Gulf Oil Spill, he produced many visually arresting images of the man-made disaster.

Over the past two decades, Beltrá's work has taken him to all seven continents, including several expeditions to the Brazilian Amazon, the Arctic, the Southern Oceans and the Patagonian ice fields. For his work on the Gulf Oil Spill, in 2011 he received the Wildlife Photographer of the Year Award and the Lucie Award for the International Photographer of the Year - Deeper Perspective. His SPILL photos toured the world independently and as part of the Prix Pictet exhibitions. In 2009, Beltrá received the prestigious Prince's Rainforest Project award granted by Prince Charles. Other highlights include the BBVA Foundation award in 2013 and the inaugural Global Vision Award from the Pictures of the Year International in 2008. In 2006, 2007, and 2018 he received awards for his work in the Amazon from World Press Photo. Daniel's work has been published by the most prominent international publications including The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, The New York Times, Le Monde, and El Pais, amongst many others.

Daniel Beltrá is a fellow of the prestigious International League of Conservation Photographers.

Daniel Beltrá's Website

Daniel Beltrá on Instagram

All about Daniel Beltrá

Aerial view of a log sorting yard carved from the Amazon rainforest near Altamira, Para state, Brazil, September, 2013.

Boats burning oil on the surface near BP's Deepwater Horizon spill source, June 2010.

After extracting the most valuable species, the forest is burned to plant soy or raise cattle, Porto de Moz, Para State, Brazil, November 2003.

Scarlet ibis birds fill the sky above flooded lowlands near the mouth of the Amazon River, February 2017

Meltwater pools within crevasses created by the melting and subsequent stretching of the Greenland ice sheet, 60km east of Ilulissat, August, 2014.

Today, we are seeing more diverse stories where individuals are a part of the natural world. By giving examples of how humanity is being impacted and adapting to the changes, it helps us see ourselves as a part of the story. Climate change is deeply personal and by making images personal, we recognize that we are all connected to it. Our destiny will be determined not necessarily by rising sea levels, but by our collective behavior.--

Ami Vitale

Nikon Ambassador and

National Geographic magazine photographer

Ami Vitale has traveled to more than 100 countries, bearing witness not only to violence and conflict, but also to surreal beauty and the enduring power of the human spirit. Throughout the years, Ami has lived in mud huts and war zones, contracted malaria, and donned a panda suit - keeping true to her belief in the importance of “living the story.” In 2009, after shooting a powerful story on the transport and release of one of the world's last white rhinos, Ami shifted her focus to today's most compelling wildlife and environmental stories. Her photographs have been commissioned by nearly every international publication and exhibited around the world in museums and galleries. She has been named Magazine photographer of the year in the International Photographer of the Year prize, received the Daniel Pearl Award for Outstanding Reporting, and named Magazine Photographer of the Year by the National Press Photographers Association, among others. She is a five-time recipient of World Press Photos and recently published a best-selling book, Panda Love; the secret lives of pandas. She is a speaker for the National Geographic LIVE series and frequently gives talks and workshops throughout the Americas, Europe, and Asia. She is a founding member of Ripple Effect Images, an organization of renowned female scientists, writers, photographers, and filmmakers working together to create powerful and persuasive stories that shed light on the hardships women in developing countries face as the climate changes and the programs that can help them.

Ami Vitale's Website

Ami Vitale on Instagram

All about Ami Vitale

Joseph Wachira, “JoJo” comforts Sudan, the last living male northern white rhino left on the planet, moments before he passed away at Ol Pejeta Wildlife Conservancy in northern Kenya. Sudan lived a long life at the conservancy after he was brought to Kenya from Dvur Kralove Zoo in the Czech Republic in 2009. He died surrounded by people who loved him at after suffering from age-related complications that led to degenerative changes in muscles and bones combined with extensive skin wounds. Today, we are witnessing the extinction of a species that had survived for millions of years but could not survive mankind.

A group of young Samburu warriors touch a black rhino for the first time in their lives at the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy, in northern Kenya. Black rhinos are almost extinct in Kenya. This young calf had been orphaned when poachers killed its mother and was hand-raised at Lewa. Poaching is not slowing down, and it’s entirely possible if the current trajectory of killing continues, rhino along with a host of lesser-known plains animals, will be functionally extinct in our lifetime.

Wildlife keeper Lekupinai is nuzzled by Twiga, an orphaned giraffe in Namunyak wildlife conservancy in northern Kenya. Twiga has been rehabilitated and returned to the wild along with three other orphaned giraffes at Sarara camp. Today, giraffe are undergoing a silent extinction. Giraffe populations have dropped have dropped nearly 30 percent in three decades, plummeting from approximately 155,000 in the late 1980s to about 110,000 today. Reticulated giraffe number fewer than 16,000. The decline is thought to be caused by habitat loss and fragmentation and poaching, but with the lack of long-term conservation efforts in the past, it's hard to know exactly.

Women and girls carry water in a remote part of Burkina Faso in the desert region near the Malian border. The village had no school and after years of waiting the parents, desperate to get an education for their children, decided to build their own. Today billions worldwide still do not have access to clean water. Women and girls spend 200 million collective hours daily seeking and hauling water for their communities, a task that steals their time and potential. In drought, they must walk for hours to find water for their families.

Samburu warriors stand at the top of the northern Kenya's Mathews Range where the 850,000 acre Namunyak Wildlife Conservancy is situated. The area is home to Africa's second-largest elephant population. There community-based wildlife keepers, like these Samburu warriors, are working to rehabilitate abandoned and orphaned elephants in order to eventually return them to the nearby wild herds. In many ways, community based conservation is likely to be the only viable alternative for vast tracts of Africa, in the parts beyond agriculture and where big animals and nomadic pastoralists still make their home. This elephant sanctuary is the culmination of a two-decades long process of tipping conservation upon its head, protecting wildlife for, and not just from people. In that sense the sanctuary is as much about people as it’s about elephants.

Naitemu Letur pushes a jug of water back to her manyatta in northern Kenya. ''Before we had this well, we would walk for many hours every day just to get water. Sometimes it was not safe but now we have plenty of water near our homes and this has made our lives more secure.''

Every year, in Bangladesh, the weather becomes more violent, more frequently. The majority of Bangladesh is made up of the massive estuary delta of the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna Rivers. Any rise in ocean levels represents a grave danger to the country. ''Even if people stopped emitting carbon dioxide tomorrow, large regions of the South would soon be underwater,'' says climate expert Atiq Rahman. Approximately 10 million people live in parts of Bangladesh lying less than a meter above current sea levels.

-

Georgina Goodwin

Georgina Goodwin is a documentary photographer and Canon Ambassador born and based in Kenya with a focus on women, refugees, social issues, and the environment. Known for her award-winning work on Kenya’s post-election violence, cancer in Kenya and Westgate terror attack, and most recently refugee children in Tanzania, Georgina is a contributor to Getty Images and Everyday Climate Change and a member of Women Photograph and African Photojournalism Database, a collaboration of World Press Photo and Everyday Africa. Her work has been published by NY Times, Elle, Vogue, AFP, and many others, and has been exhibited in Times Square NYC, Tokyo Japan, and The Louvre Paris amongst others. Georgina was a speaker at TEDxKakumaCamp, the first TED talks to be held at a refugee camp, and one of 19 finalist speakers at TEDx Nairobi in 2017.

Georgina Goodwin's Website

Georgina Goodwin on Instagram

All about Georgina Goodwin

An Amhara boy looks after his family's last remaining horse in barren fields of Ethiopia's northern Washira region, June 2008.

In 2008 northern Ethiopia had 2 consecutive seasons of failed rains and was in the throes of another devastating drought that was on the verge of breaking into a disaster famine similar to the one in 1983-5. Northern Ethiopia's Washira region in July 2008 allegedly lost 250,000 cattle and 16,000 people, fields that were supposed to be full of tef (an annual species of lovegrass native to the northern Ethiopian & Eritrean Highlands and the Horn of Africa) were barren, dead, or dying animals, and food aid. Rains did come a few weeks later with no large-scale famine.

Fisherman Basomo Salim, 40 (centre) Athman, 38 (right) get ready to go out on their boat Firdawsi at Kiunga village on the Kenya-Somali border. We spend more and more time out looking for fish. When we started 15 years ago there was so many fish, now some days we don't even bother to go out. All of us have noticed this, May 2017.

Overfishing is responsible for some of the lowered catch in Kiunga, but there is another problem contributing: the lack of food for the fish themselves causes by global warming.

Satellite data shows levels of phytoplankton - the microscopic plants which fish eat - falling dramatically in some of the most biologically productive regions in the tropics such as near the Kenyan and Somali coasts. Parts of the Indian Ocean have warmed by 1.2 degC over the last century, this slows the mixing of surface water and nutrient-rich deeper waters and stops nutrients from reaching the phytoplankton living at the surface. Climate models project the Indian Ocean will continue to warm due to increasing greenhouse gases, potentially turning this biologically productive region into an ecological desert.

Amina Suleiman Gas, 45 stands amidst the carcasses of her dead animals, piled for burning outside the compound where she has lived for 10 years in Barwako village 20kms into the desert from Anaibo Town, central Somaliland. She sent most of her livestock west with her neighbor in November 2016 when the drought began to get worse and fears they have not survived March 2017.

Barwako was a village of 100 families but 245 more came in from the surrounding area because of the drought. As a member of the Village Savings and Loans Association (VSLA) Amina and her group shared all their savings with the displaced families, leaving them with nothing. At least 6.2 million people, more than half the population, were in need of assistance after four consecutive seasons of failed rains over three years leaving the region depleted of all its resources and experiencing a drought on a scale not seen since 1974 and on the verge of famine.

A young Masai boy brings his cows back home at sunset in Kenya's south Rift which is experiencing longer dry spells and inconsistent rain patterns, December 2014.

The African continent has warmed about half a degree over the last century and the average annual temperature is likely to rise an average of 1.5-4°C by 2099, according to the most recent estimates from the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Annual rains in Kenya's south Rift are now no longer guaranteed and the rain, if it does come, is less. Masai children are taken out of school in order to take care of the livestock that is now needing to travel greater distances from the homesteads to find any form of pasture. These greater distances mean the livestock return later to the boma or homestead, often after sunset.

The already arid environment of Kenya's south Rift coupled with the huge increase in population and livestock numbers and increase in tree cutting for charcoal are all exacerbating climate change issues further.

20 year old Masai Serem checks the dawn soil moisture while his lifestock drink the Embirika water point, piped fresh water from the Ngurumen Hills behind, December 2014.

Kenya, like the rest of the world, is experiencing climate change and variability and the associated adverse impacts. Taken during the area's dry season in Kenya's southern Rift this image is from a photo series looking at the issues that are surfacing due to the gradual climate change of less annual rainfall, failed rains and increased pressure on resources by human and livestock populations. The changes are gradual but are noticeable: The level of the Ewaso Nyiro river, the area's lifeline, in some areas fell by 12ft, and still generators were being used to pump water from the river into the drying soil of the crops. Grass literally vanished leaving pastures of thick fine dust. As pressure on resources increases, our need to implement protection and mitigation strategies becomes even greater.

Climbers near Stella Point on Kilimanjaro's rim at sunrise, a view of the vertical margin wall can be seen of what is left of the Rebmann Glacier, a small remnant of what was the enormous icecap which once crowned Mount Kilimanjaro, 14 October 2016.

What was once a solid ice climb is now scree and rock with the ice that forms over the very cold nights quickly disappearing as the sun rises. About 90% of Kilimanjaro's snowcap has vanished, the rate of glacier shrinkage has doubled since the 1970s. There are many forces driving the climate in this region, one being the increased dryness of East Africa (the cause of droughts and famines in Kenya, Ethiopia, and Sudan) which scientists say may be the key driver of glacier shrinkage and may in fact be speeding up due to global climate change. Rapid population growth has caused traditional subsistence farming to expand into previously virgin areas, increasing the rate of deforestation of Kilimanjaro's forest, a key component of its catchment capacity. What is happening on Kilimanjaro is a microcosm of what could face the entire world in the future. Kilimanjaro remains an important laboratory for studying glacier loss around the world and for measuring the effect of climate change on atmospheric circulation.

Thank you very much to all the photographers who took part in this article. We are thankful for everything you do.