''Nkanga, and her work, remind me of the great Ghanaian photographer James Barnor. After developing his practice in London, Barnor too returned to his familial home, bringing the skills learnt overseas to capture the likeness and lives of neighbours, family, and fellow Ghanaians. Through these tender and stylish works, Barnor documented an evolving place, a nation undergoing major changes. Nkanga achieves a similar homecoming, operating on a introspective, communal, and state-wide scale. She captures the people of Akwa Ibom somewhere in the blurred midpoint between documentary and street portraiture, and has no interest in unblurring that line.''

—Isaac Huxtable, writer and curator

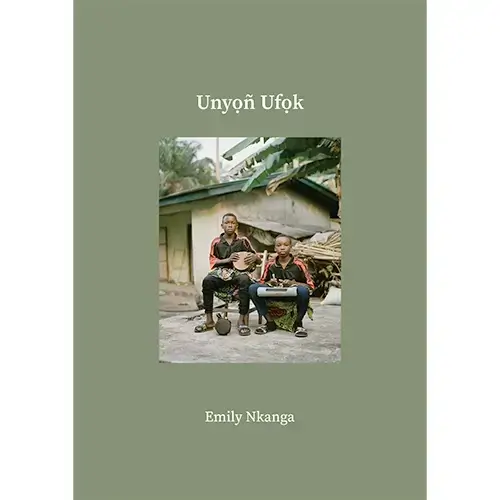

Emily Nkanga, photographer and filmmaker, presents Unyọñ Ufọk (translation: Going Home), a photo book exploring grief, identity, and home. Through analog photographs shot on Mamiya RZ 67 and Olympus OM2, Nkanga captures fleeting moments of everyday life in her hometown of Akwa Ibom, Nigeria. The images act as a time capsule, preserving the beauty of life’s transient moments.

The project began in January 2021 when Nkanga returned home for her father’s burial. After living in the UK for more than seven years, she was struck by the love her father—a beloved patriarch who “changed the generational story” of their family—received from the community. This inspired her to document life in Akwa Ibom. Over nearly two years, Nkanga photographed local life, from governance and monarchy to unsung heroes, including a youth boxing club. The book is comprised of a three-part project.

“I feel like I almost had a duty to [document] Akwa Ibom, from the inside, at least.”

Among the subjects documented are members of traditional music bands, the Ikemesit Cultural Group and Starlight Cultural group. “In traditional Ibibio society, music is seen as a cohesive and spiritually potent force,” Nkanga writes. The book includes portraits of band members with their instruments—a metal gong akankang, bamboo block ntakrok, rattle nsak, and more. This connection to music reflects Nkanga’s background, having worked with Sony Music, Universal Music, and Warner Music.

“Music surrounds us from the moment we are born, through all parts of life including religion, marriage celebrations, illness and – finally – funerals, which are often seen as a celebration of life.”

Another focus is the Akwa Ibom state boxing team. Nkanga’s photographs document the dedication of two coaches, one a former Olympian, who train young athletes. Their story is further explored in Nkanga’s documentary Reaching for Gold, featuring two female boxers, Dorcas Onoja and Idara Udoette. The book includes portraits of the team and their coaches, capturing moments of discipline and community.

The book also explores the Nigerian tradition of mourning. Nkanga photographed individuals wearing commemorative clothing featuring her father’s likeness. These fabrics, used in celebrations and mourning, symbolize shared memory. Nkanga’s father was mourned by local politicians and royalty, including Oku Ibom, “Priest of the Almighty God of Ibibio”, who is the traditional ruler of the Ibibioland in Akwa Ibom. The inclusion of these moments underscores the community’s respect for her father and their cultural traditions.

“What started as mourning activities grew into a reflection on the society her father helped form.”

—Isaac Huxtable

An Okada man waiting for a passenger. February 2022 © Emily Nkanga

Sunrise in Ewet Housing, Uyo. January 2021 © Emily Nkanga

My grandfather, Elder Okon Udo Nkanga, in his room. February 2022 © Emily Nkanga

For Nkanga, Unyọñ Ufọk, a project both personal and reflective, became a therapeutic means of redirecting grief into art. In Akwa Ibom she learned her father was nicknamed Idongesit Akwa Ibom, translating to “Comforter of Akwa Ibom.” Through the book, Nkanga creates a portrait of her father, not as a single figure, but as a composite of the lives he touched. “It gives a bit of closure,” she reflects, “especially for someone who really loved my work. I feel like if he saw these pictures, he would be happy.”

The book also asks broader questions about identity and belonging. “What is our connection to our homes? What, and where, is home?” Nkanga reflects. Though deeply rooted in Akwa Ibom, her time abroad lends her a distinct perspective, allowing her to document the community with both familiarity and curiosity. Unyọñ Ufọk is a time capsule, a family archive, a regional diary. As community elders pass on, a new Akwa Ibom is forming.

Boxers training. February 2021 © Emily Nkanga

A boxer in front of the training gym. February 2021 © Emily Nkanga

Victory Centre, Ikot Obio Edim. January 2021 © Emily Nkanga

Women in commemorative outfits of my father, Idongesit Okon Nkanga, for his burial. February 2022 © Emily Nkanga

One of the palace aides: Eteidung Ekom J.O. Ekanem, Village Head of Ndiya Ikot Ukap, Nsit Clan, Nsit Ubium Local Government Area. June 2022 © Emily Nkanga

Emily Nkanga is a Nigerian-British multidisciplinary artist working across photography and filmmaking. Her work focuses on exploring the lived experiences of individuals within the complexities of everyday life or popular culture.

Her documentary project Narratives of Displacement: Conversations with Boko Haram Displaced Persons in Northeast Nigeria, which documents internally displaced people affected by the Boko Haram insurgency, was published by Taylor & Francis.

Nkanga is also well-known for her work capturing notable artists and athletes including Thierry Henry, Whoopi Goldberg, Alex Iwobi and Olamide, and working with global companies such as Sony Music, Universal Music and Amazon Studios. Her work has been featured across a wide range of publications, including the British Journal of Photography, Okay Africa and the BBC.

She has an MA in Filmmaking from Goldsmiths, University of London, and a BSc in Communications and Multimedia Design from American University of Nigeria.

www.emilynkanga.com

@emilynkanga

Elisha Uko Asuqwo and his bamboo block ntakrok, Ikot Nya, Akwa Ibom. February 2021 © Emily Nkanga