Steff Gruber is a renowned Swiss photographer whose career spans decades of impactful visual storytelling. Beginning as a press photographer for Keystone Press, Gruber's work quickly gained recognition for its depth and narrative power. While he is well known for his pioneering contributions to the docudrama genre in filmmaking, it is his photographic work that has consistently pushed boundaries.

Gruber's passion for human interest stories has taken him to various countries, where he has documented diverse subjects through his compelling photo stories, often returning multiple times to deepen his understanding of the people and places he captures. His work is celebrated for its striking visual language and his bold approach to narrative, which continues to push boundaries in both photography and film. His project

Railway Community won the Solo Exhibition in June 2023.

We asked him a few questions about his life and work.

All About Photo: Can you share your first experience with photography? What attracted you to this field?

Steff Gruber: When I was only four years old, my father used to take me to a photo studio. At the time, he worked as a graphic designer and was responsible for creating the catalogue for Switzerland’s biggest fashion mail order company. In the dressing room, I was allowed to play with the 120 film spools which the photographers used in their Hasselblad cameras – surrounded by half-naked models, who fascinated me even then. Since then, I have associated photography with technology and eroticism. Two fields that have remained central to my life ever since...

What is the best advice you received when you were starting out?

Even from a young age, my parents advised me not to let financial concerns dictate my career choices. They encouraged me to do what I felt was right and what I really wanted to do. We’ve passed on the same advice to our two sons. Our older son became an architect, the younger one studied psychology – neither of them careers that bring in a lot of money, at least not in the early years. My advice to young photographers is the same: If you really want something, it will work out!

How do you manage your time between your work as an entrepreneur, filmmaker and photographer and are all activities as equally important to you? Why?

This has always been my biggest challenge, and it still is today. Why are there only 24 hours in a day? I often joke, sardonically and self-critically, that if I’d concentrated on just one profession, I might have been more successful! But having such a wide range of interests is evidently an intrinsic part of who I am. For years, I’ve also been a pilot and, as a radio operator, I regularly write articles about radio wave propagation for a specialist magazine. However, I find greatest fulfilment in photography. An anecdote comes to mind: When Karl Lagerfeld was asked about his profession, he always identified himself as a photographer, rather than fashion designer, despite the latter being his primary profession.

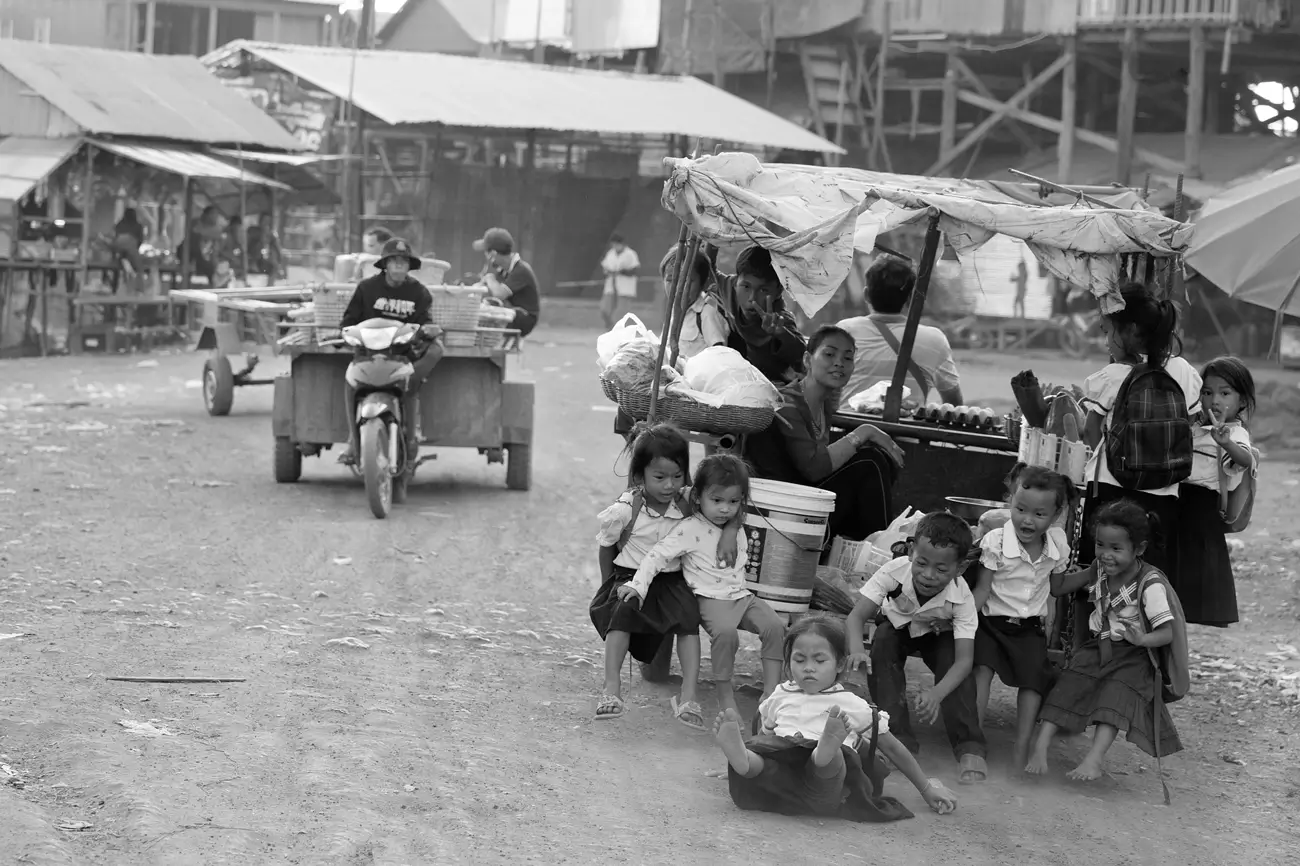

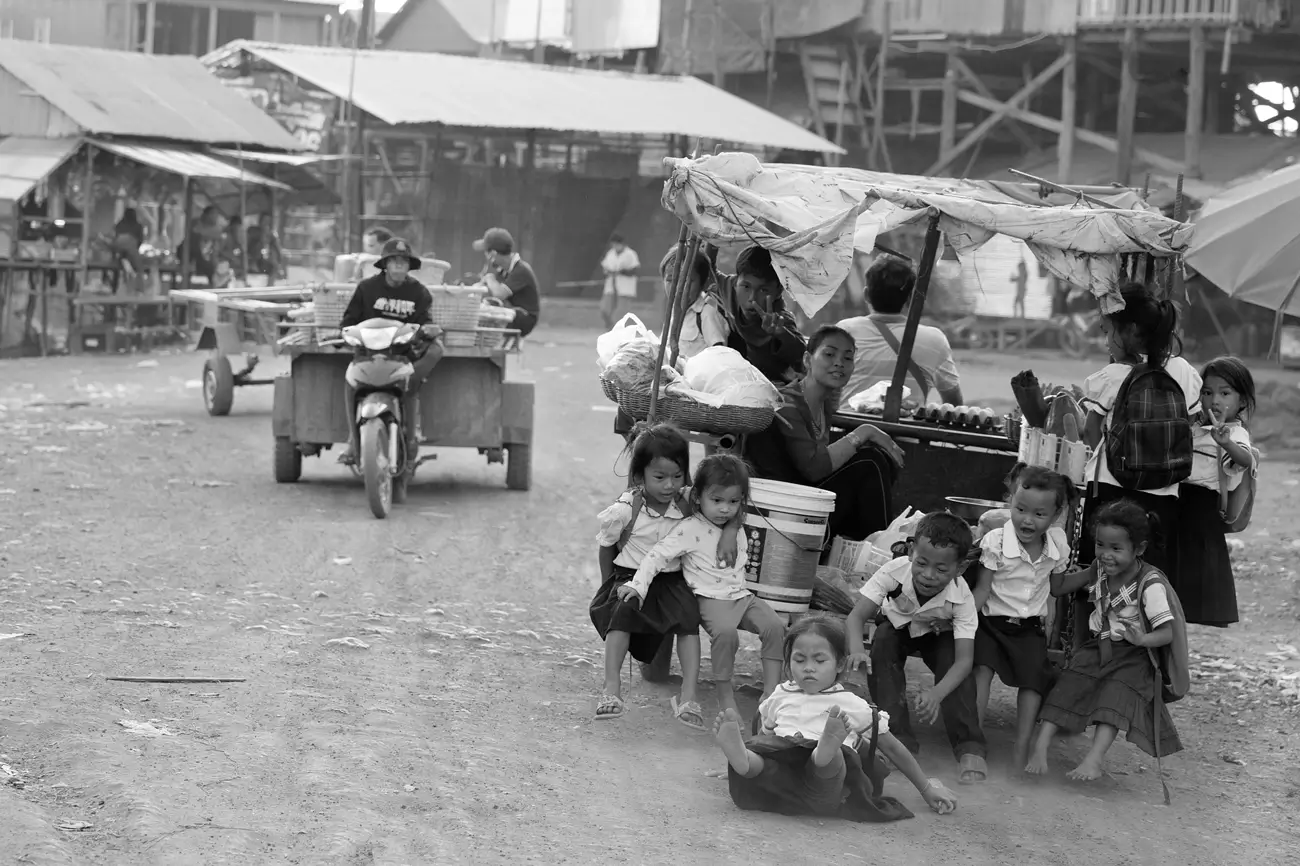

Living on Water, Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia © Steff Gruber

Living on Water, Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia © Steff Gruber

Living on Water, Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia © Steff Gruber

In my feature films, as an author and director, I have always pursued questions that resonate with me personally. How do we function in two-person relationships? Or why are relationships between the sexes so difficult? With my documentaries, however, it often felt like the subjects found me. For instance, the German director Werner Herzog invited me to Africa to make a film

LOCATION AFRICA about him and his leading actor, Klaus Kinski.

In documentary photography, which has become my greatest passion, I am drawn to people and communities who haven’t been as fortunate as I have. Growing up in Switzerland, with access to a good education, excellent healthcare, and minimal financial concerns, I feel exceptionally privileged and I’m profoundly grateful for this. Now I want to show the Western world that there are millions of people who are not doing so well. I’m especially interested in displaced populations. In Cambodia, for instance, I have been visiting and documenting such communities for years. Time and again, I sense how grateful these people are that someone cares about their plight, even if we can’t really help them.

Do you finance your trips or is your work commissioned?

That’s a valid question, because my projects are indeed very costly. This is because my approach to photography is similar to my filmmaking process. It starts with the research. I employ a researcher, Diana Bärmann, who conducts in-depth investigations into our subjects from Zurich, documenting and organizing everything in advance. My long-time producer and assistant, Chris Jarvis, a Canadian who has spent almost his entire life in Southeast Asia, travels to the shoot locations one or two months ahead of me to handle all the on-site logistics. He generates interest in our projects, coordinates local fixers, drivers, and interpreters. He also books flights, hotels, rents cars, boats, and so on. So when we shoot, we’re always a team.

Only in recent years have the sales of these photo series started to offset production costs. To finance my projects, I pursue another passion of mine: inventing company and product names. I develop them, have them protected, and then sell them to companies. For instance, I invented the name XBOX years ago and sold it to Microsoft, who used it for their games console. I’ve also sold a name to one of Elon Musk’s ventures.

Why do you mainly work in Asia?

There’s a nostalgic reason. Even in my youth, I was captivated by the novels of Graham Green, Rudyard Kipling, and Margarete Duras. Sometimes, I feel like my photography is a way of secretly capturing a bygone era. Not out of nostalgia for colonialism, of course; I am well aware that many of today’s problems were caused by colonialism in the first place. But when I watch a rickshaw driver battling through torrential rain in Phnom Penh at three o'clock in the morning, I occasionally feel like I’ve been transported back to the days of Indochina. To return to your question: Yes, Southeast Asia, even the new, modern one, has cast a spell over me!

Which country or people have had the greatest impact on you?

Although I haven’t been back much since my youth, the USA holds a special place for me. When I was 20, I spent a year in Athens, Georgia, where I attended courses at the university and immersed myself in an artistic community that still influences me today. This was primarily the art scene surrounding Jim Herbert, a painter, filmmaker, photographer, and professor. On his porch, I met people like Cindy Wilson from The B-52s, Silva Thin, who worked at Andy Warhol’s Factory at the time and often visited us in Athens, and Bonnie T, a gifted photographer. She taught me a lot about portrait photography. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to track her down for years...

A year before I went to Athens, I attended art school in Zurich. My main photography teachers there were Serge Stauffer and Peter Jenny. Serge had taught Oliviero Toscani a few years before as well as many other photographers who later gained international acclaim. The late sixties and early seventies was a remarkably vibrant period for photography – even in Zwinglian, iconoclastic Zurich, of all places!

Genocide museum S-21 in Phnom Penh © Steff Gruber

Genocide museum S-21 in Phnom Penh © Steff Gruber

I definitely consider my work to be political, particularly my documentary photography, simply through my choice of motifs – the people living between and on the graves in a Phnom Penh cemetery being one example. But there are also deeper levels of meaning. For example, in one picture of a family, a girl is holding a large bag of chips. One of the major problems in the Third World (and increasingly in some Western countries) is nutrition. Children, in particular, live off fast food. In the same photo, you see another young girl in a beautiful dress reminiscent of a princess. You wonder how people who otherwise have nothing can afford such expensive clothing. I’ve noticed this phenomenon all over Southeast Asia. I learned that Western aid organizations regularly deposit (used) clothes outside slums. These and similar messages hidden in my images naturally require the viewer to engage deeply and do their own research if they want to fully understand them.

That’s what I love about photography. Unlike most documentary films produced today, which often present «good» and «evil» in a polemical way, nuanced documentary photography requires viewers to engage on a deeper level. Although I primarily shoot in black and white, photography can tell stories that are not merely «black and white». The truth often lies somewhere in between. Distinguishing between good and evil isn’t always straightforward. While my work reflects my subjective perspective – I decide what the viewer sees when I frame the photo – I am committed to conveying the truth.

Smor San, Phnom Penh, Cambodia © Steff Gruber

These demands are based on a vague fear of AI, a mystical acronym that no one really understands...

But to answer your question: I think this is a completely misguided development. Not just because there will soon be a «hack» that will manipulate or bypass such measures, but also because it stems from a fundamentally flawed understanding of truth. As I just said, you can manipulate an image simply by cropping it. A good example of this is Nick Ut’s famous image of a naked 9-year-old girl, screaming in agony and panic as she flees from a Vietnamese village, which has been bombed with napalm by the Americans. The photo was subsequently cropped by the photographer or photo editor to focus the viewer’s attention on the girl’s immense suffering. It’s said that this image contributed to the Vietnam War ending shortly after it was published globally. In my opinion, manipulation that conveys the horrific reality of such a brutal war is always legitimate. The concept of «truth» is complex, and it certainly can’t be guaranteed by technology. As Bob Dylan once said: «The truth has many different levels!»

The biggest «manipulation» is the photographer’s decision about where to point the camera and which images to publish – what to show and what not to show. I think that, in some cases, a manipulated image may come closer to the truth than an unedited one. These are theoretical considerations for me, because I still belong to the old school that considers image manipulation in documentary photography to be taboo. But let’s imagine you take a photo where war crimes can be seen in the foreground, and in the background, bombs are being dropped and a city is burning. What if that background was captured five minutes earlier, for example? Does that change the image’s message? I find questions like this fascinating... I have Nick Ut’s «Napalm Girl» photograph in my collection, signed by both the photographer and the girl (Phan Thị Kim Phúc, who survived after more than 30 surgical procedures), 50 years after she fled the burning village in Vietnam.

For me, it’s very important to own original versions of the photographs that have influenced my work...

So you are also a collector?

Yes, I consider photography to be the center of my life, and that includes collecting pictures by my colleagues. But I collect photographs according to certain rules. The pictures and their photographers must have played an important role in my life. For instance, René Groebli gifted me one of this pictures. As a friend of my parents, he was around during my youth. But I also have pictures by Jock Sturges, Sebastiao Salgado, David Yaron, Beat Presser, Nobuyoshi Araki, Daido Moriyama, Stefanie Schneider, Sarah Moon, Karl Lagerfeld, Louis Stettner, Jan Saudek, Ansel Adams, Bonnie T, Francesca Woodman, Larry Clark, Pierre Boucher, Mario Giacomelli, Bert Stern, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank, Willy Ronis, Alfred Eisenstaedt, Josef Sudek, William Klein, and many more. I also collect historical photographs, for example by Lehnert & Landrock, which were taken in North Africa at the beginning of the last century.

Railway Community, Phnom Penh, Cambodia © Steff Gruber

Railway Community, Phnom Penh, Cambodia © Steff Gruber

Between 2009 and 2014, I shot the feature film

FIRE FIRE DESIRE in Cambodia and Thailand. In search of locations, my producer, Chris Jarvis, and I explored every corner of Phnom Penh on foot. We were literally out all day and all night. While we were out walking, we stumbled upon lots of fascinating places that we didn’t need for the film at the time. For example Smor San, the cemetery where displaced people lived. We also met the people living on Tonle Sap Lake for the first time. We returned to these places after we’d finished filming and began to portrait the people there.

How did you work?

My method is very complex. Firstly, I always work with a team and secondly, we never visit a place only once. You can’t build trust unless you visit the same people regularly over the course of many years. I maintain you can see this trust in my pictures. The people we meet often ask us our advice, with unexpected questions like: «Should I marry this guy or not?» Since we know these people and their everyday problems intimately, I feel comfortable offering my opinion. Whether or not they follow our advice, of course, is another matter...

What was the population’s response to your camera?

We always engage with the people we photograph, so the reactions are consistently positive.

Is your work sometimes dangerous?

I’m frequently asked this question, and my answer is always the same. From our experience, not only in Southeast Asia but also in Africa and Latin America, the less people have, the kinder and more helpful they tend to be. For example, once, while shooting in a poor neighborhood in Phnom Penh, I stood up suddenly from a crouched position where I’d been working with my camera and smashed my head against a razor-sharp sign I hadn’t noticed. It was almost 40°C, too. I evidently lost consciousness for a few seconds, and when I came to, I found myself lying in the street, surrounded by a crowd of people excitedly discussing what had happened. One of my colleagues arrived on the scene, and we soon realized my bag and all my cameras were missing. I assumed a thief had run off with all my belongings in the commotion. Given the poverty in the area, I quickly accepted what had happened and in my mind had already forgiven the thieves. I had to deal with my bleeding head first anyway. After someone had given me water and wrapped my head in a makeshift bandage, I stood up unsteadily and caught sight of two little girls sitting at the top of a staircase, each protectively holding one of my cameras in their lap. I felt ashamed of my initial suspicion... So, to answer your question: Yes, it is sometimes dangerous, but the danger never comes from the people!

How long did you stay in Phnom Penh?

I have been visiting Cambodia regularly every year for the past 17 years. Phnom Penh is almost always our base camp... I feel just as much at home there as I do in Zurich or on the Balearic Islands, where my wife and I own a house.

Tonle Sap Lake Community, Cambodia © Steff Gruber

Tonle Sap Lake Community, Cambodia © Steff Gruber

Tonle Sap Lake Community, Cambodia © Steff Gruber

In some countries, professional-looking cameras are treated with suspicion. I remember once gaffer-taping the camera to my body and trying to hide it under a thick winter jacket to cross the border from Moldova to Transnistria. The customs officials searched everything thoroughly, and my translator and driver were even taken to a little hut for body searches. For whatever reason, I was allowed to wait by the car, which they also searched. They even used a mirror on wheels to inspect the underside of the vehicle. But it wasn’t until the next day, back in my hotel in Moldova, that I felt really uneasy. At breakfast, an OECD employee told me the story of a BBC cameraman who had been caught filming illegally in Transnistria by the secret service and whose body was then discovered floating in the Dniester River... Despite that, I still went to Transnistria with my camera a few more times. With hindsight, I’d say this wasn’t a very wise idea. I certainly wouldn’t do it today.

What was your biggest challenge?

A night shoot in a slaughterhouse outside Phnom Penh. We had the rare opportunity to spend a night witnessing the process of pigs being slaughtered. I wore earplugs to block out the infernal noise, and I shielded myself from the stench with several face masks over my mouth and nose. The visual aspect didn’t affect me so much because I was watching everything on the black-and-white monitor of my Nikon mirrorless camera. But my assistant – who, incidentally, is a vegetarian – wanted to quit after the shoot. I had to promise him we’d never do anything like that again. Even I couldn’t eat meat for at least a month after that...

Secret slaughterhose near Phnom Penh © Steff Gruber

Secret slaughterhose near Phnom Penh © Steff Gruber

I’m a bit of a tech freak, and I’d never say that it doesn’t matter what kind of camera you use. That’s complete nonsense! Cameras are tools, just like those used by craftsmen. A builder on a construction doesn’t use any random drill: He picks the best one for the job. And to stay with the construction site analogy: When it comes to pouring concrete, he doesn’t use a drill at all but a compactor, which is a completely different tool. It’s the same in photography. When I’m shooting reportages, I always use the top-of-the-range Nikon, upgrading to the latest model every two years. Although these cameras are equipped with an additional shutter to protect the sensor from dust, I never change lenses when out in the field. Many of my colleagues praise the advantages of fixed focal lengths, but for reportage work, I rely solely on zoom lenses. The quality of Nikkor lenses is now so high that I doubt you could spot the difference... The downside of these cameras, of course, is that they are big and heavy. That’s why we always have a Leica Q3 with us. It’s saved my life more than once, like last January in Mumbai, India, when I had to photograph in a densely built slum, with alleyways barely half a meter wide. The Leica is perfect for those kinds of situations, and also in the evenings when I get tired from carrying around my camera.

The available lighting is rarely sufficient for our needs, so we almost always take our own. During the day, we typically use large reflectors, while in the evening and at night we rely on LED cine lights or a portable Profoto flash system.

For my art and experimental photography (which I do too!), I use pretty much every type of camera that has existed – from the large-format Sinar and various Polaroid models, Hasselblad, Rolleiflex and analog Leicas to my first analog Nikon, which I purchased in 1970. Occasionally, I even take pictures with homemade pinhole cameras.

Do you spend a lot of time editing your work?

Yes, Anselm Adams’ books have had a profound impact on me. I’ve internalized the «Zone System», and it usually takes me over an hour to edit each image with Photoshop. That’s only possible if you shoot photos in RAW format, which I always make a point of doing.

This brings me to the question of theory. Do you also work with other photo theorists besides the aforementioned Ansel Adams?

Alongside my extensive collection of over 2000 photo books, I own virtually everything that has ever been written about photography. I spend hours studying the work of other photographers! Art books, such as those on Caravaggio and Rembrandt, are very enlightening, too.

I usually read the works of the great photography theorists and philosophers several times over. Understanding the ideas of people like Roland Barthes and Susan Sontag is crucial to taking a meaningful photograph. Even if I don’t always agree with John Berger, I need to know what he thinks about a particular subject. The theories of philosophers such as Theodor W. Adorno, Walter Benjamin and Ludwig Wittgenstein influence my perspective and worldview, as do the films of Jean-Luc Goddard. I am currently exploring the subject of analog versus digital techniques, both in photography and in print.

What compliment touched you the most or what do you think is your biggest accomplishment?

When my friend, the photographer Beat Presser, says: «Wow, that’s a Henri-Cartier Bresson!» But jokes aside, we all know that artists thrive on applause. It makes me happy, too, when one of my pictures touches someone. I’m also delighted whenever I win a prize in a competition or when pictures are picked for exhibitions. Compliments used to leave me cold. I only ever created things for myself. I’m probably getting old...

Tonle Sap Lake Community, Cambodia © Steff Gruber

I had planned to visit one of the world’s largest refugee camps, the Rohingya camp in Bangladesh, in January 2024. Everything was set – travel arrangements, permits, and so on – but I contracted Covid in India and had to postpone the trip. Maybe we’ll go there eventually. I also want to return to India and Cuba, and of course, Ghana, which I haven’t been to since 1987... I’m eager to realize at least some of these projects and plans. I’m also working on photo books and magazines. The first, titled «Voyage of Dreams», which features pictures from my time in the US in 1974 and includes a foreword by the German art historian Ulrich Schneider, will be published soon.

An anecdote you would like to share?

A few years ago, a teacher from a village school near Kampot in southern Cambodia took me to his home on his motorbike. We arrived at a lake. He stopped and I was struck by the beauty of the landscape, but also by the profound silence. The stillness was almost eerie and a shiver went down my spine, despite the fact that it was almost 40°C! I turned to my new friend rather startled. He told me that when he was 12 years old, the Khmer Rouge henchmen had made the area unsafe. Thousands of people had been murdered and their bodies thrown into this lake. He said he would never forget the smell of decaying corpses that had lingered in his village for months. I took a photo of this landscape. I think the tragedy of that place is palpable in the picture.

Landscape, Lake in South Cambodia © Steff Gruber

«The greatest thing since peanut butter,» says one of the protagonists of my short film BOYS ARE BOYS AND GIRLS ARE GIRLS, which I shot in Athens, Georgia in 1976. Although this was the answer to the question: «What do you think of Women’s Lib?».

I can only answer this question in a differentiated way. In Switzerland, high-tech medicine has been successfully using AI for many years, especially in diagnostics. Even my dentist told me he only found a hidden cavity thanks to his AI program. I often use DeepL Write to check the style and grammar of texts I’ve written in German, and this proofreading program improves from week to week. But your question probably refers to image design. And this is where my enthusiasm hits a wall. What bothers me is not so much the lack of technical possibilities (although these too are improving by the week), but the fact that the people behind ChatGPT and co. want to impose their moral standards on us. Have you ever tried to edit or create an artistic (in the truest sense of the word) nude photo? You’re instantly reprimanded and warned about potential exclusion from the platform for violating its terms of use. In the past, I would have attributed this to the perverse, reactionary morality of certain US religious fundamentalists. Today, of course, I know it reflects a broader global consensus on these issues. I find this behavior amongst AI companies deeply unsettling. It alarms me because it shows a growing trend among corporations and governments to not only restrict my artistic freedom but also interfere with how I think. Why doesn’t this bother anyone but me? I believe it’s our duty as artists to stand against this all-encompassing and restrictive «political correctness» and a morality that is becoming increasingly paternalistic.

Anything else you would like to add?

Thank you very much for the interest you have shown in my pictures and for giving me the opportunity to present a solo exhibition on your platform, it is an honor!

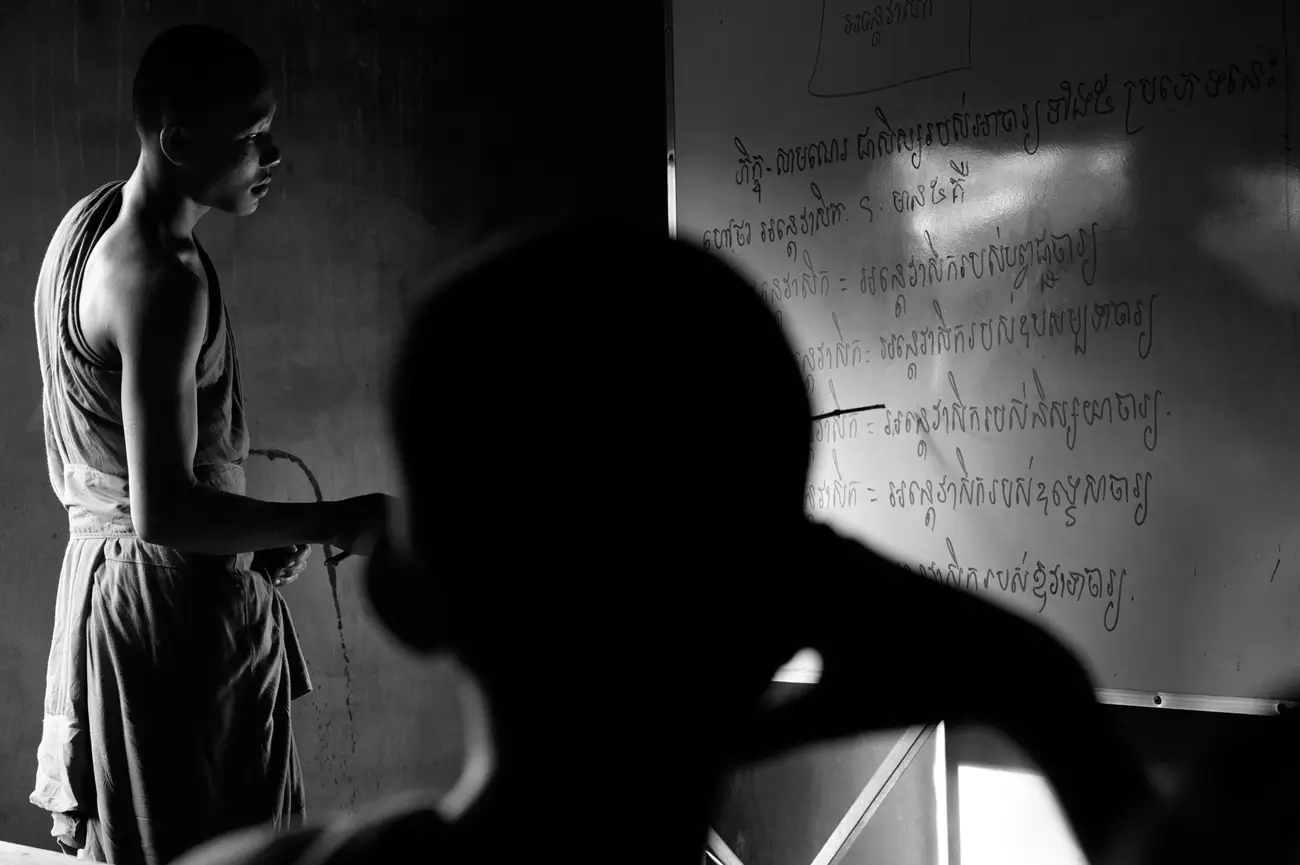

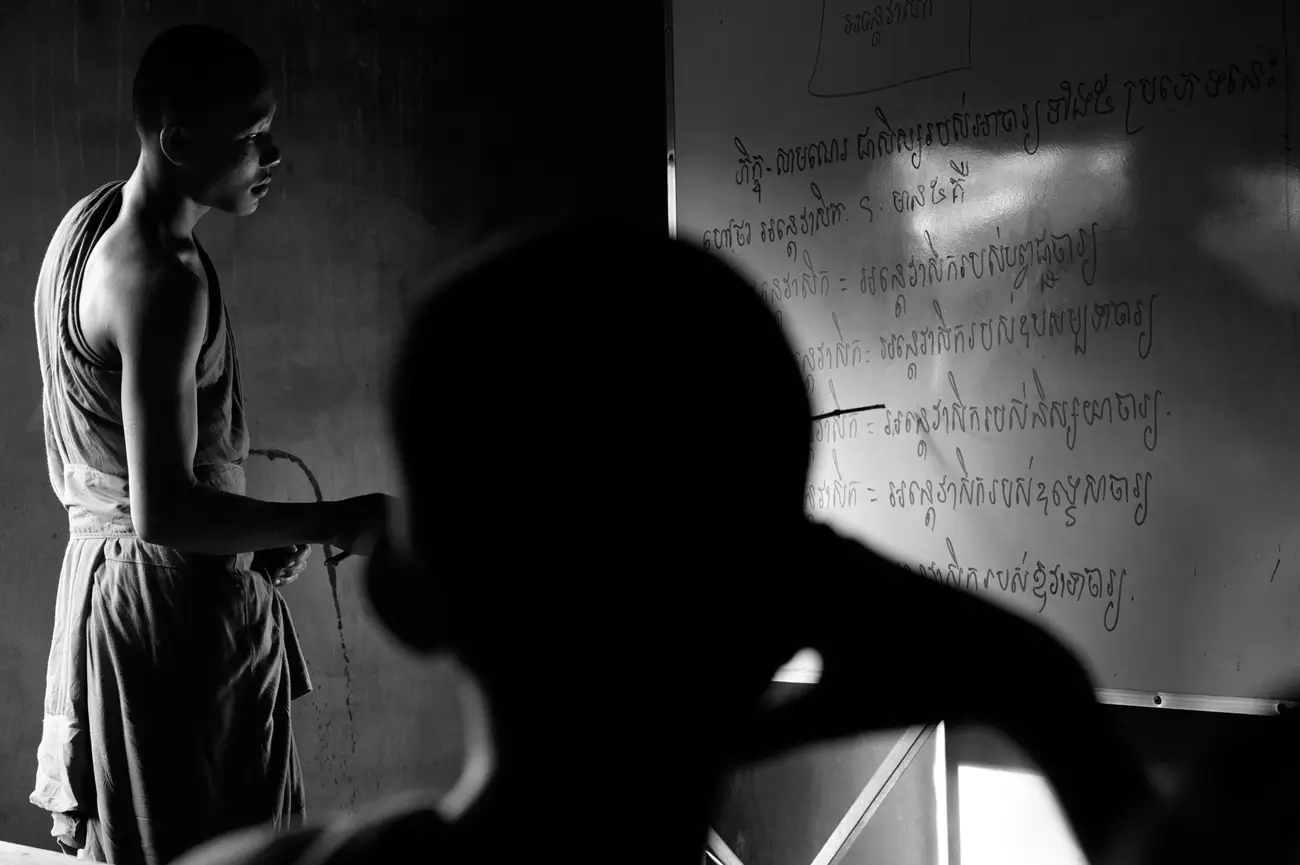

Theravada Buddhist Monastery near Kampot, South Cambodia © Steff Gruber

Theravada Buddhist Monastery near Kampot, South Cambodia © Steff Gruber