''Mozart's sensuous music and devotion to the pleasures of the world are to be associated less with ultra-rational geometry and

architecture than with the pictorial worlds of a Francisco de Goya – and especially, the multiplying of forms and thoroughgoing

ambivalence of feeling... unify the most heterogeneous elements of reality into an ideal whole''

– Denis Diderot (1713-1784) French Critic & Philosopher

Immanuel Kant had said,

''All our knowledge begins with the senses, proceeds then to the understanding, and ends with reason...'' The

business of images today, in whatever applicable form for any reason, is an imperative, and as indispensable as breathing. In this and the

forthcoming photo-investigations, I will attempt to decipher the morphology of our senses, their importance, their evolution and the

contemporary science behind understanding these faculties, and the part they play in general, especially, in our particular pursuit. My

vocation of photography is actually the daily practice of sensing, it is for me the means, to identify, discover and propose aesthetic

dimensions that would appeal to our senses, that are yet undiscovered and uncatalogued.

Osmotic photography: One could ask, why, for heaven's sake, should we delve into some recondite material like neural morphology of our

sensing faculties – all we are doing is taking some pictures. Actually, no we don't have to. We could continue taking pictures based on our

aesthetic sensibilities and they could very well serve the purpose. But, our work will be a basic record wanting depth or dimension. It's like

the difference between a casual tourist landscape versus an Ansel Adams composition. Becoming an Ansel Adams or a Henri Cartier-Bresson

is like becoming Ernest Hemingway or Hilary Mantel, countless years of study (all subjects) and preparation – and such preparation

invariably favor consistent depth and dimensional aspects that raise our work above the common denominator.

The key to anticipation, becoming prescient, sharpening our instincts, timing and composition on the fly that enables us to predict an

unforeseen event, human condition or action, is actually predicated on how much knowledge one had assimilated, over and above their

talent. The induction of knowledge is not a static but a dynamic concept, the dynamic aspect being practice. Knowledge when applied over

time results in osmosis that in turn results in wisdom, that equips one to presage conditions before they unfold, that others cannot. Induction

of knowledge is the only elixir-aqueduct to wisdom. The advantage of this is that one is prepared and ready, beyond the angle or perspective,

light and composition, for that flash moment like when someone's eyes reveal, ever so briefly, their tragedy or rapture.

Osmotic photography is, when the aggregate of experiences, techniques, and more so knowledge, evolve to wisdom in a trial-error process,

in the service of image creation. To become aware of this phenomenon, the osmosis of knowledge to wisdom, begins with the ingestion of all

kinds information, from neural systems to night vision goggles. Osmosis is a process that churns every singular and disparate experience of

ours into a thick nutritious shake that fuels our discernment – therefore output. Not withstanding prodigies, why are the best surgeons

mature-older, why are astronauts in their late thirties-forties, and why are leaders always older? It's because of their accumulation, through

various experiences, the ossification of nuances into their repertoire, organic and inorganic, in a specific avocation that enables better

decision making and therefore, results. And yet, we exist in total uncertainty, therefore, preparation becomes paramount.

It was never clarity that had brought about my adrenaline rush – rather, it was the nebulousness, that uncertainty, of the portents or

possibilities of the unknown. What we can see is specific, what we sense is the ambiguous, the unknown, yet the whole. This fetches such

questions: Do we first see or sense? Or do we first sense, before all else? We feel and sense atmosphere, we cannot see it, its not discrete,

something specific, but the whole. Seeing is a physical act, a retinal registration, a complex neural process of induction and interpretation.

Sensing is invariably comprehensive, a complex interdependent neural computation. Images distilled through our senses are perhaps

complete. Therefore, sensing leads to seeing the whole. Senses are the gateway to reality – yet, they do not disclose all of reality. Nothing

ever does. However, people who can sense or intuit conditions or forthcoming trends are special – in many cases visionaries.

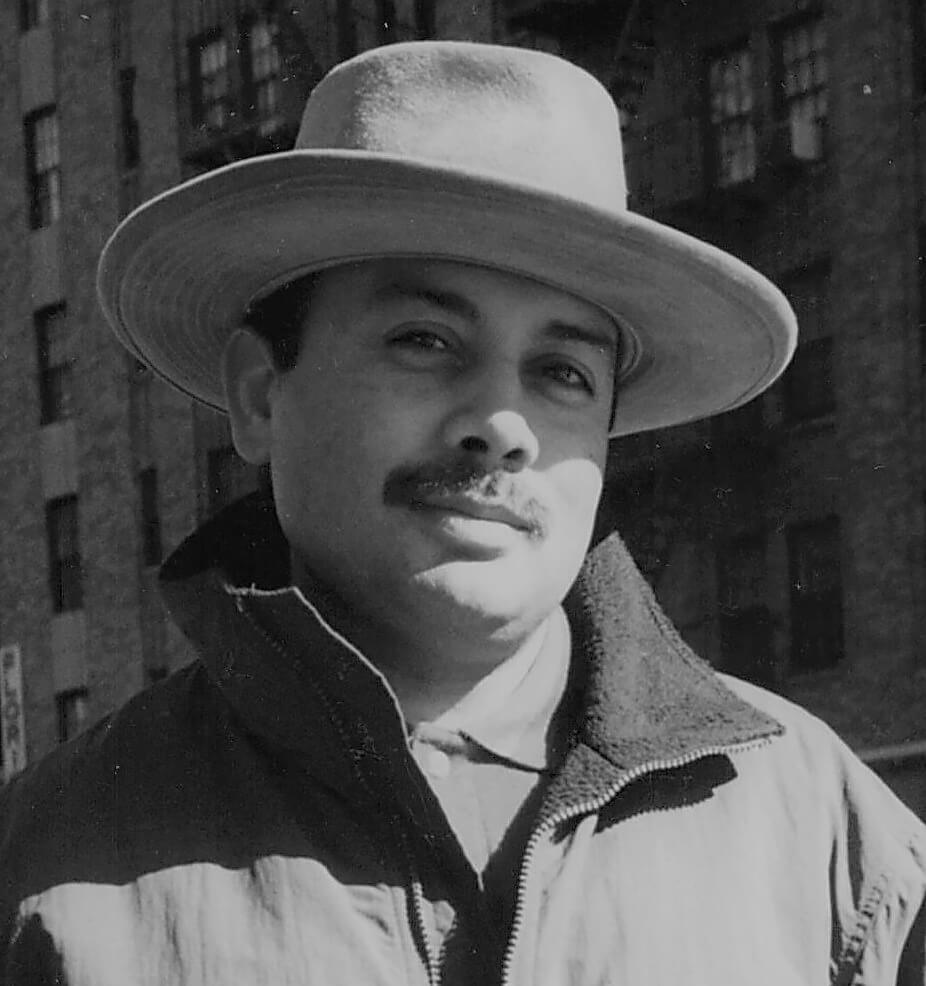

Photograph No.1: Here are two experiences that had induced this pursuit – this is something that would slide by us without our notice, but,

I couldn't help marvel at what had unfolded one recent Saturday morning. I had heard the basement shower go on, and a few minutes later I

tiptoed and pried open the door slightly to attempt an Art Shay like prank (Nude of Simone de Beauvoir) on my wife. But, to my surprise, she

was already waiting for me, looking directly at me through the textured glass, with her tongue stuck out, goading me, with a “Gotcha!”

expression. I had no inkling of how she had presaged my presence.

Atmospheric Soup © Raju Peddada

Atmospheric Soup © Raju Peddada

Photograph No. 2: Last weekend, I had left at 3.45am to escape the inexorable Nietzschean traffic on I-294S, headed for Tennessee. As

soon as I had merged onto I-65S, what awaited me was a Lovecraftian nightmare, a milky 70mm panorama with no horizon. I had to adjust

the speed to what I could see, which was nothing. If Edgar Allen Poe with William Friedkin had designed a scene of surreal horror, this

would be it. As the highway curved sharply and straightened out, I saw this bright blob materialize abruptly at a distance, heading directly

for me. Within seconds the blinding blob filled my screen and veered off to my left – it was a vehicle across the deep median, heading in the

opposite direction. The illusion had left my heart racing, while I had crawled to a stop. The pervasive atmospheric soup had swallowed me –

couldn't see anything. This prompted my contemplation – How could I sense the whole, yet see nothing? By what mechanism does this

happen? Why does sensing give us better information than seeing something specific, yet it's not enough? To find an understanding – we

must start in the mid 18th century literature, then ease into modern science for answers.

Literary basis: I am certain of the literary theorists and their earliest literature addressing such issues. We would serve ourselves well by

immersing ourselves in literature, for it is the wellspring of the human psyche and its myriad conditions, Shakespeare, Robert Burton and

Charles Dickens being our earliest teachers. The German literary thinker, Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht's little gem of a treatise titled

“Atmosphere, Mood, Stimmung” is a deep focus lens on the concept of sensing, atmosphere and feeling that could easily crossover to our

photography. David Wellbery, a literary critic, had translated an extract on the concept of “Stimmung” from “Aethetische Grundbegriffe,” an

Olympian collection of writings by several Germans on aesthetic principles, ideas and concepts. Stimmung means, '...the feeling in myself

and the feeling between us...” He also examines Goethe's essay, “Falconet,” that illuminates how we experience the encompassing unity and

harmony in very common place settings – senses and sensations in the most ordinary of circumstances. It's not far-fetched to have these

literary principles carry over to photography.

Scientific basis: Is there the possibility of cross pollination of epistemological principles to the scientific constructs? The progress from

literary speculation and theorizing to scientific certainty is like George Lucas's imagination of worlds beyond in his Star-Wars saga that had

induced the Reagan SDI (Strategic Defense Initiative) , more so the “why not” with engineers, to the realization of several concepts at

DARPA. Stanley Kubrick's “2001 A Space Odyssey” in 1968 had presaged the shuttle program and the space stations. Imagination is the

only conduit or funnel to realization – by virtue of this alone the interconnection exists – a neural algorithm.

What started out in Literary speculation and theorizing centuries before, had now evolved and diversified into imaging systems, to genome

and genetic discoveries, to cognitive psychological experiments, and, to eventually Neurology. These contemporary capacities have given us

a manifest picture of the five Aristotelian senses in shaping our perception of our abstract and logical or rational world around us. What is

new are the astounding discoveries and reality of the interconnected activity of our senses, their proximity and balance of structures yielding

thirty-three additional and discrete senses, one of them being Nociception, (a sensory nervous system process of encoding noxious stimuli),

and that our prescience, had been underestimated or underrated, and invariably, does not depend on any one single sense.

No sense operates independently. The interactions between the inter-wired senses gives us a coherent perception. The old computer relied on

a simple switch referred to as a transistor (now microprocessor) that had a single function: on and off, like one of our many senses. But the

use of multiple interconnected senses to perceive and view simultaneously from all perspectives is akin to quantum computing – quantum

sensing is like electrons operating in multiple dimensions for many faceted results. These are paradigm shifting discoveries and insights.

Finally, this is just the beginning – this is the setting, of the attempt in understanding ourselves as to why we do discern, and why our

discernment is dependent on our perception, beyond the Darwinian natural selection. I will leave you with some questions to ponder: what

are the chances that a Mendelian gene, specific to genius or a particular talent, a basic unit of heredity, traveling for millennia though chance

ascendants is gifted to you at a fetus stage? What is the likelihood that we can calculate the number of ascendants it took to give you a

specific talent, or affliction? What are the prospects that you or your parents will realize that you have this gift (like Mozart's father, Leopold

did)? What are the odds that you or parents (mostly self-centered and clueless) will nurture this gift you have? And what are the chances that

you will stand on your genius and be recognized? You would be less than 0.0001% of the special ones that had made it.

Ninety-nine plus percent of the folks rely on the acquisition of knowledge to make a living. But 99 plus percentage of folks with that gift of

genius also fail to realize their potential – why? Because, people do not nurture their talents by attaining knowledge and with practice.

Mozart is an example of relentless study and practice, he analyzed Bach, Hadyn, Salieri and other peers of his day, everyday for hours upon

hours – he was improvising as a preteen, something his middle-aged peers couldn't. To Mozart, music was his poetry for the senses. Isn't this

a lesson?

Copyrighted July 17, 2024, Raju Peddada / All Rights Reserved on the Text and Images.

Djinns Light © Raju Peddada

Djinns of Light © Raju Peddada