Imagine motorcycles unlike any others you’ve seen before, ornate mechanical confections like Fabergé eggs with engines, exquisite but hard-boiled — and big, resplendent in the variety of their design and spectacular enough to be arrayed on pedestals in a museum. In fact, they were.

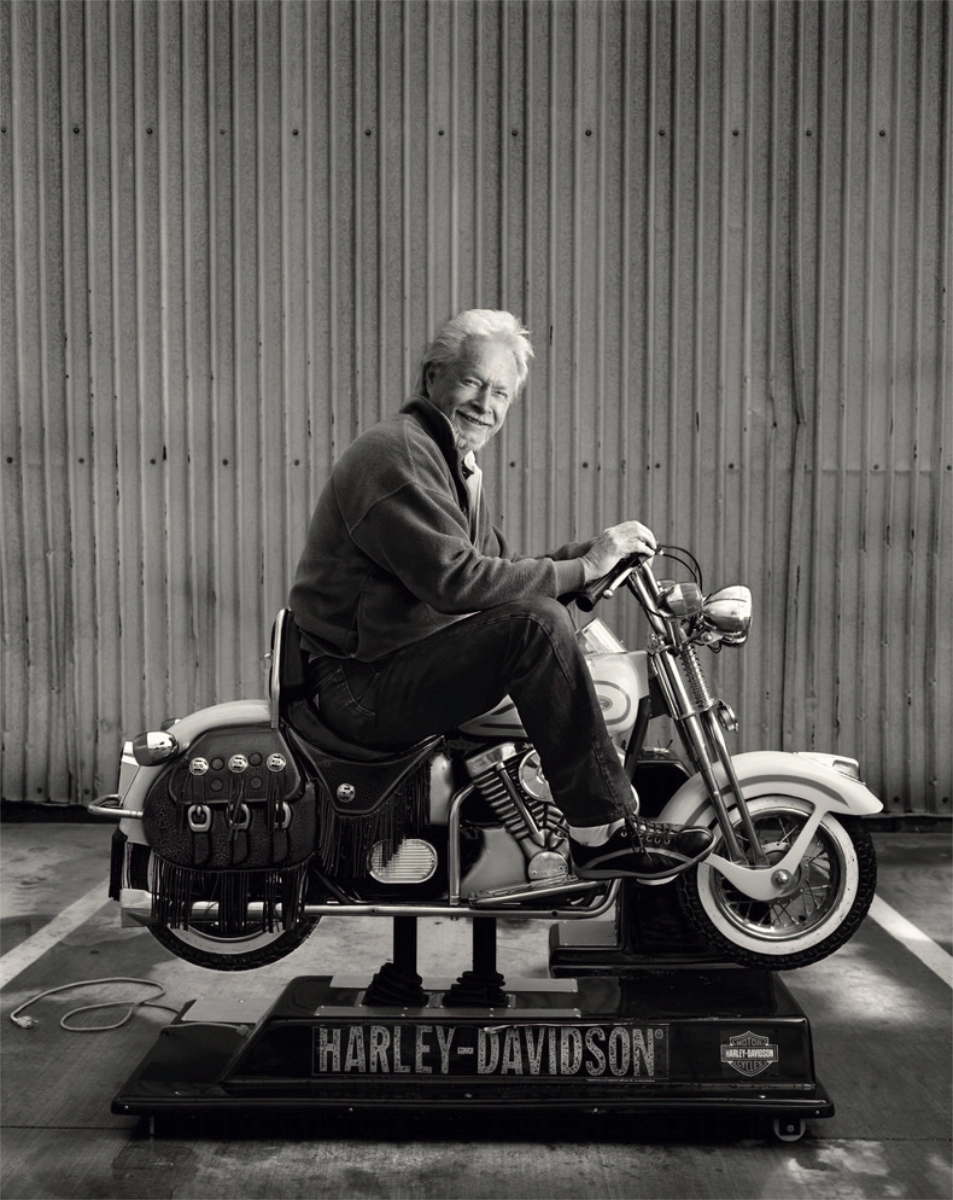

Riding my Harley-Davidson through San Francisco, heading home to Sausalito — five miles more through traffic, then freewheeling across the Golden Gate Bridge, I thought I’d wait out the sweltering heat of an early summer day. There was no hurry, no need to lane-split. I could park on the sidewalk in front of Pier 23, a funky waterfront bar and café where passing tourists on the Embarcadero would stop to admire my beast while I quaffed a cold beer.

It was hard not to miss several black SUVs with bubblegum lights on top parked near my usual spot. Someone important must be inside. No one stopped me from rolling onto the sidewalk. I put the kickstand down, dismounted, unfastened my brain bucket, and asked one of the men in black speaking into his sleeve, “So who ya got in there?” He nodded sideways at the open front door, where I could see Bill Clinton sitting alone at the bar eating a hamburger.

“Any problem my going in?” I asked. He shook his head to indicate no problem.

Sitting at a table to my right as I entered were a half dozen men and women, recognizable by their dress and demeanor: staffers. I removed a

Pocketfolio from my jacket pocket, a 4½- x 6-inch, richly printed-and-bound portfolio of black-and-white photographs, my calling card, always at hand because, long before it was practicable to pull an iPhone out of your pocket and display pictures on a screen, it was tiresome to respond to the curiously naive question: “What kind of pictures do you take?” My

Pocketfolio included portraits of a U.S. president and a secretary of state, plus some movie stars. I scribbled a note on the frontispiece, then approached the table. My note requested a minute with Clinton to ask about doing a portrait like the one of President Reagan he could see for himself a few pages in. But these folks didn’t know me from some biker off the street.

“Would one of you please give this to President Clinton?” I said, proffering my little portfolio. They looked up at me with

Who let this madman in? on their faces, ready to summon the Secret Service agents. I held out the

Pocketfolio again. One man took it and flipped through. He brightened. He passed it around.

I shot him an inquisitive look, palms up.

“Sure! Come on. I’ll introduce you,” the man said. He walked me to the bar.

I sat next to Clinton and ordered a bottle of Anchor Steam. We chatted. He was noncommittal about sitting for a portrait, citing his schedule and telling me that he was in town for his daughter Chelsea’s graduation at Stanford. Then he said, “Hey, I really like your Harley jacket.”

I said, “If you like the jacket, you oughta see the bike.”

“Is it here?” Clinton asked.

“Yes sir, Mr. President,” I said, “just outside the door.”

“Well, let’s go see it, Tom!” Clinton climbed off his bar stool, put his arm around my shoulder, and led us out of Pier 23.

Word had spread; there was now a crowd on the sidewalk. I hollered, “Fifty bucks to anyone who’ll take a picture.” (Someone did and, later, sent me a print.) Clinton, meanwhile, walked over to my teal-and-chrome, 800-pound baby and threw a leg over. While he sat astride, I cranked the engine. Wild Bill Clinton was having a ball, twisting the throttle at the expense of everyone’s eardrums. You could see on his face how much he would have loved to tear off down the Embarcadero on that bike. Like, sure, that was going to happen! I don’t think he knew how to ride, anyway. He got off. I got on. I waved goodbye and rode home.

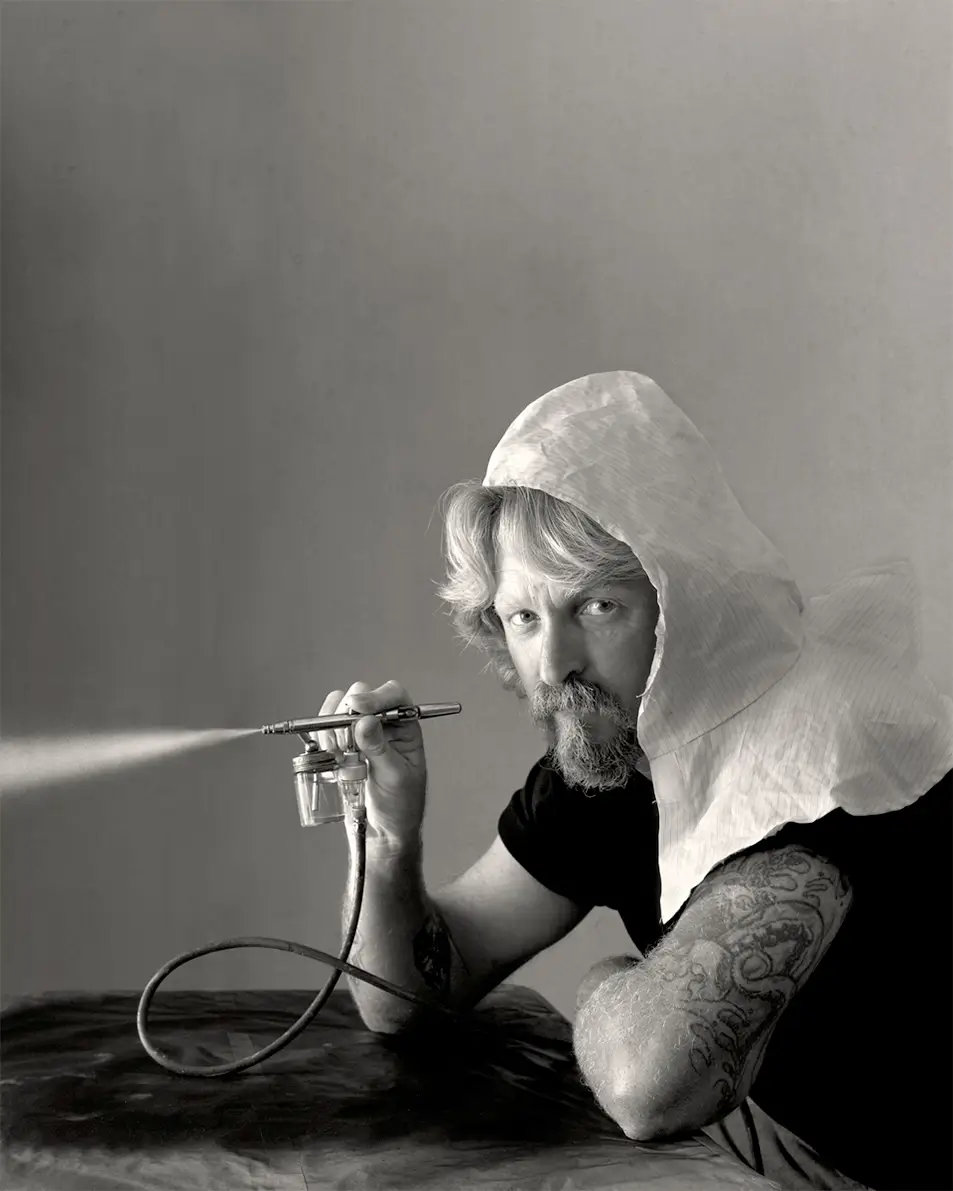

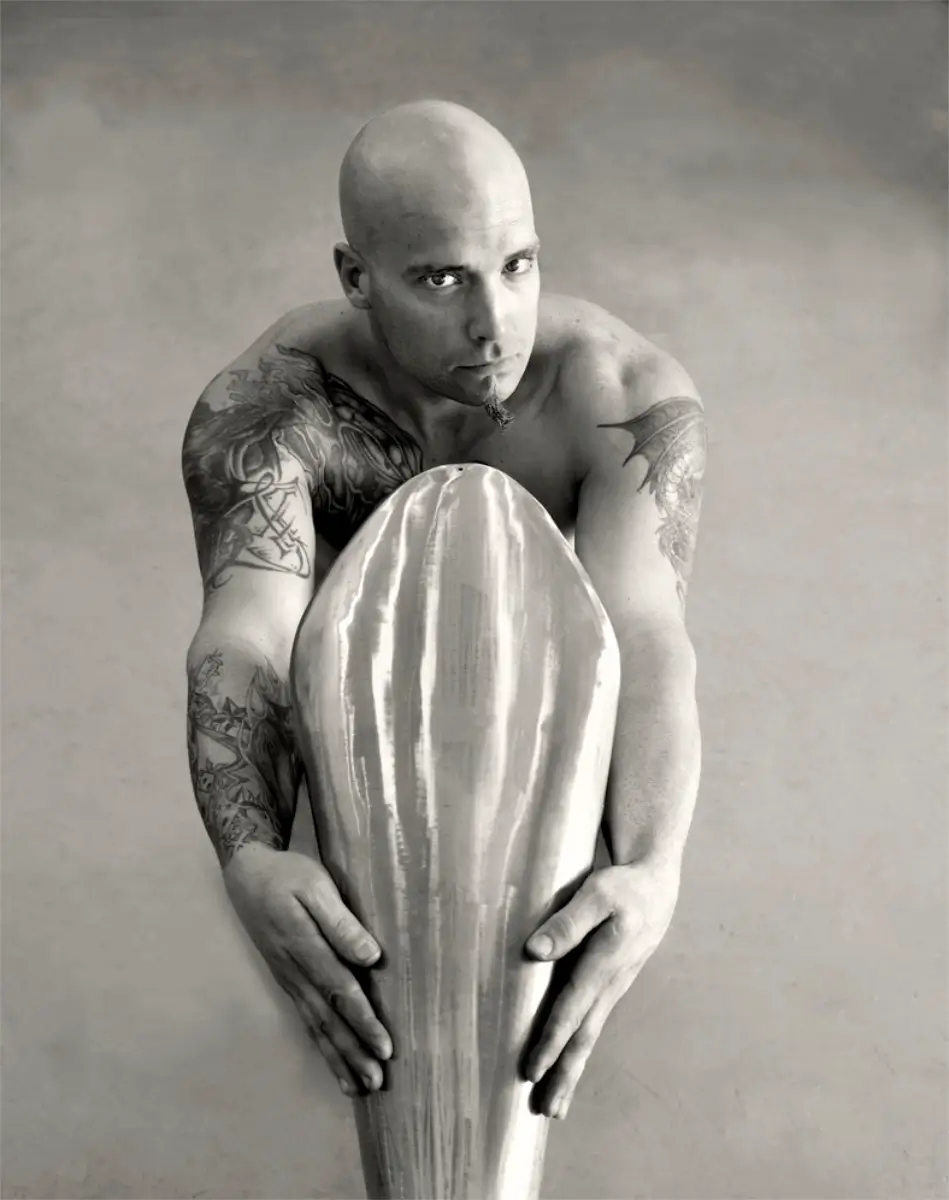

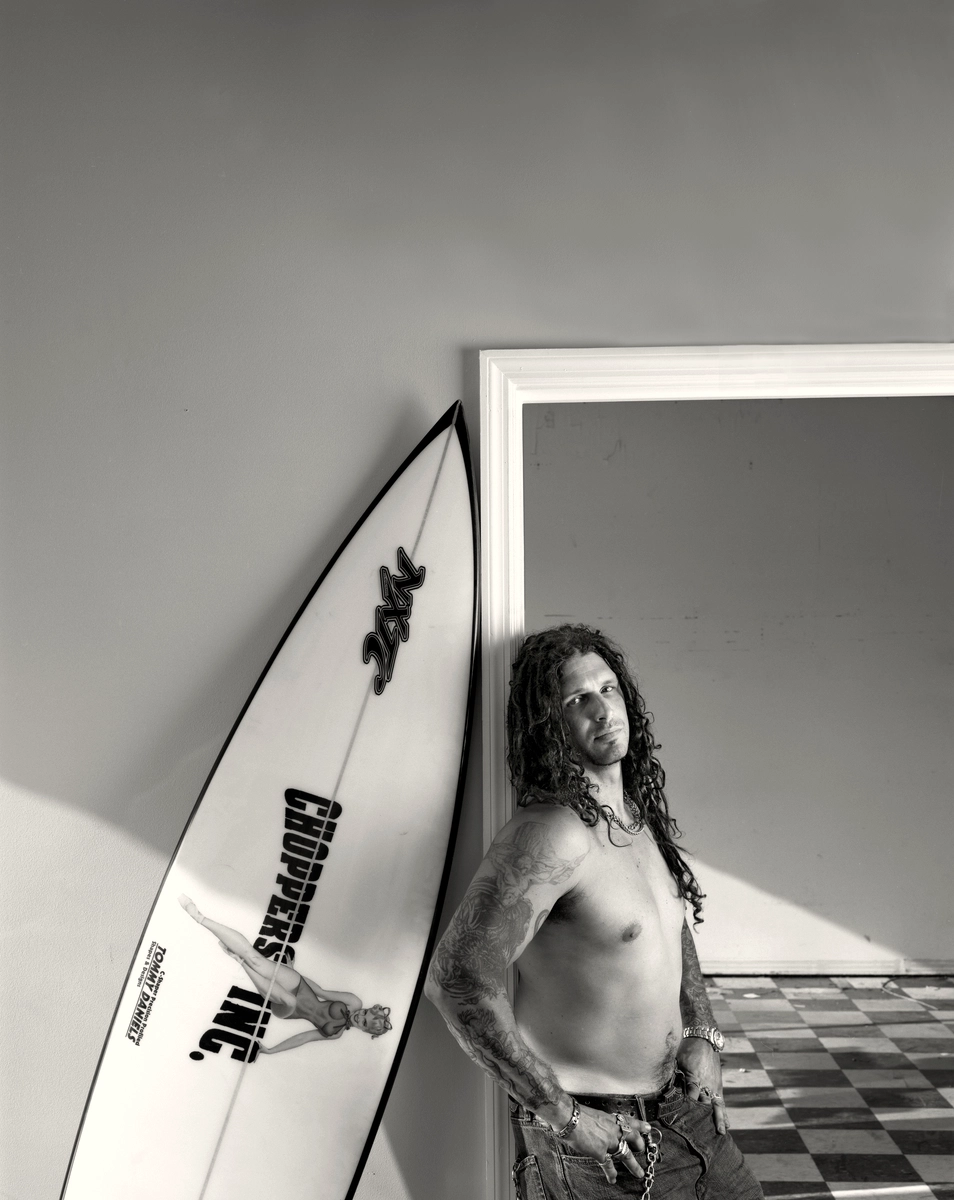

Mitch Bergeron © Tom Zimberoff

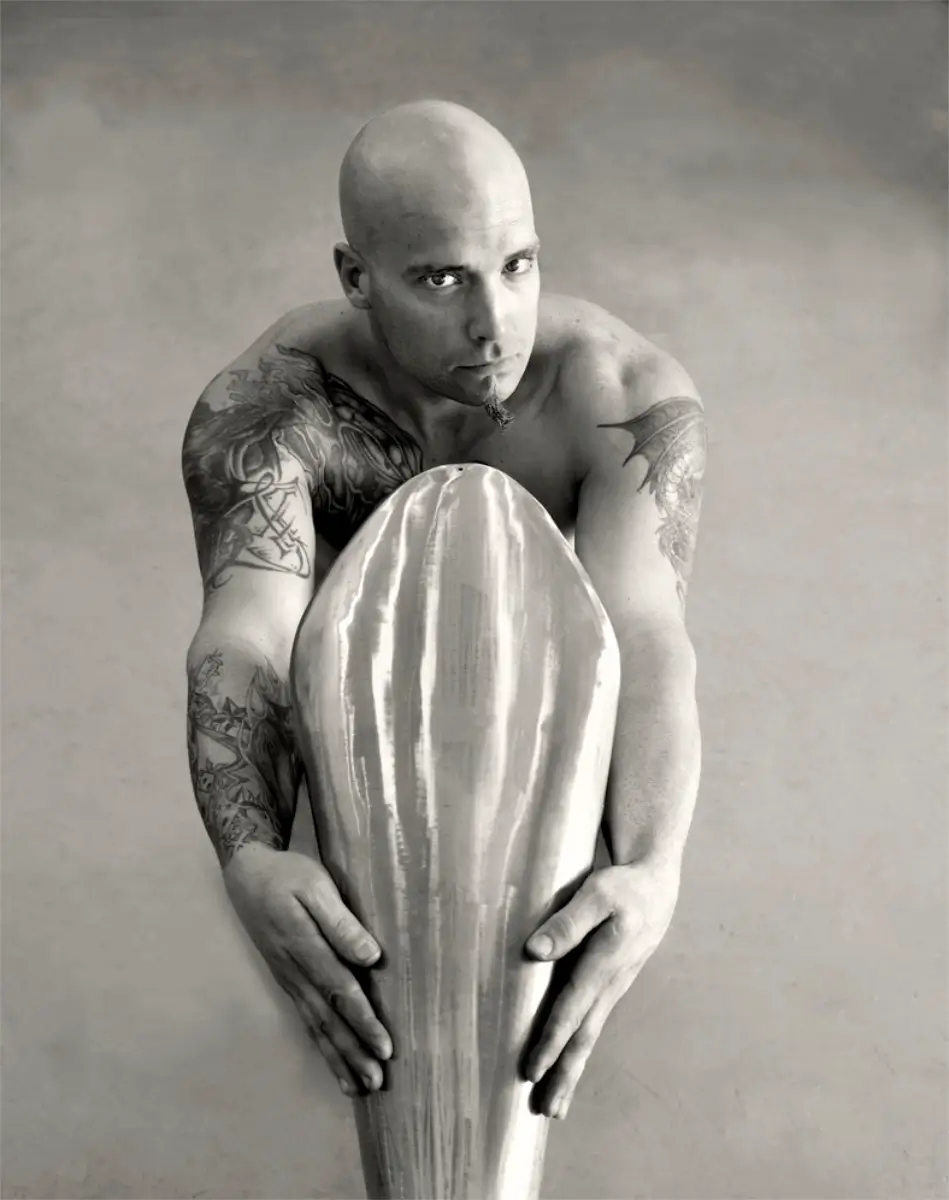

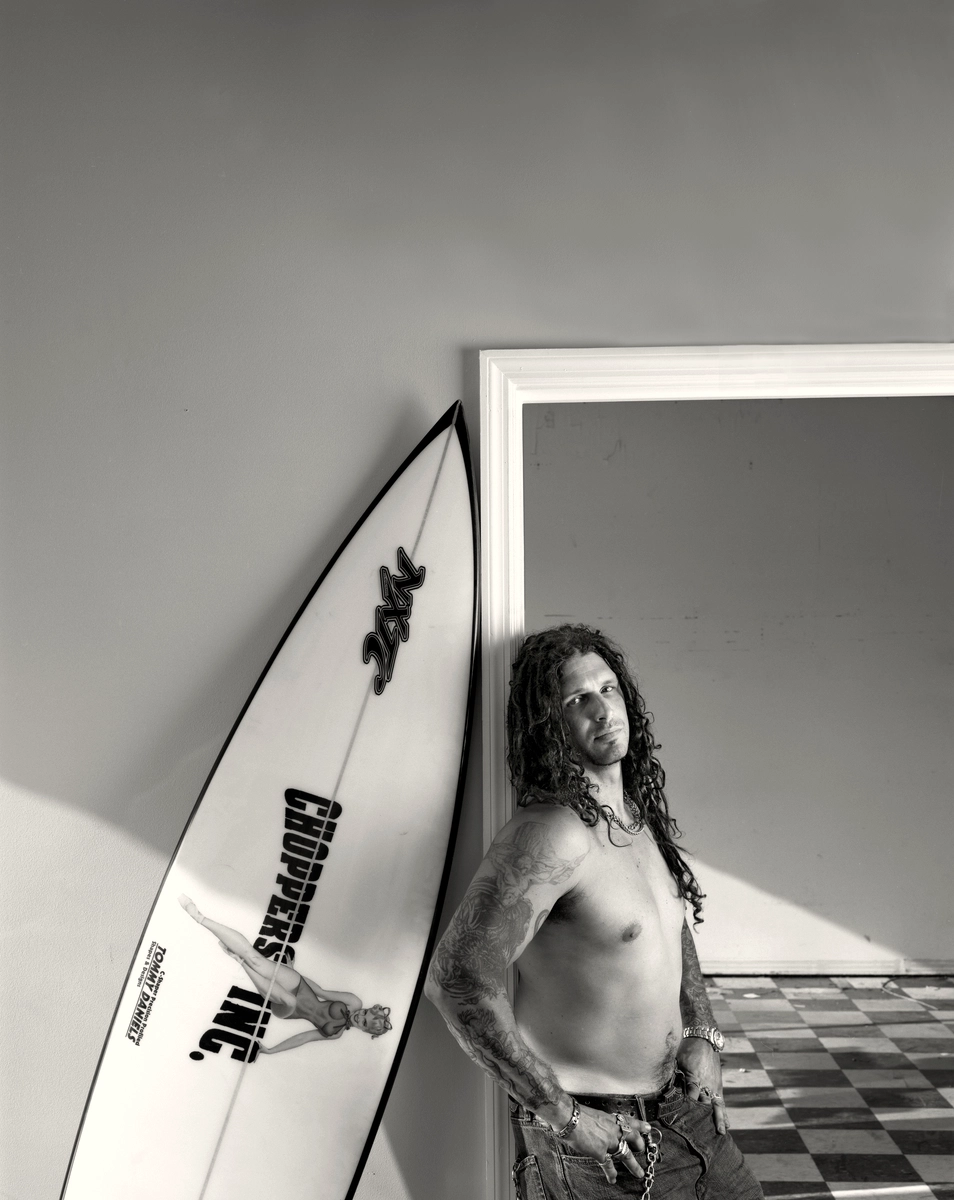

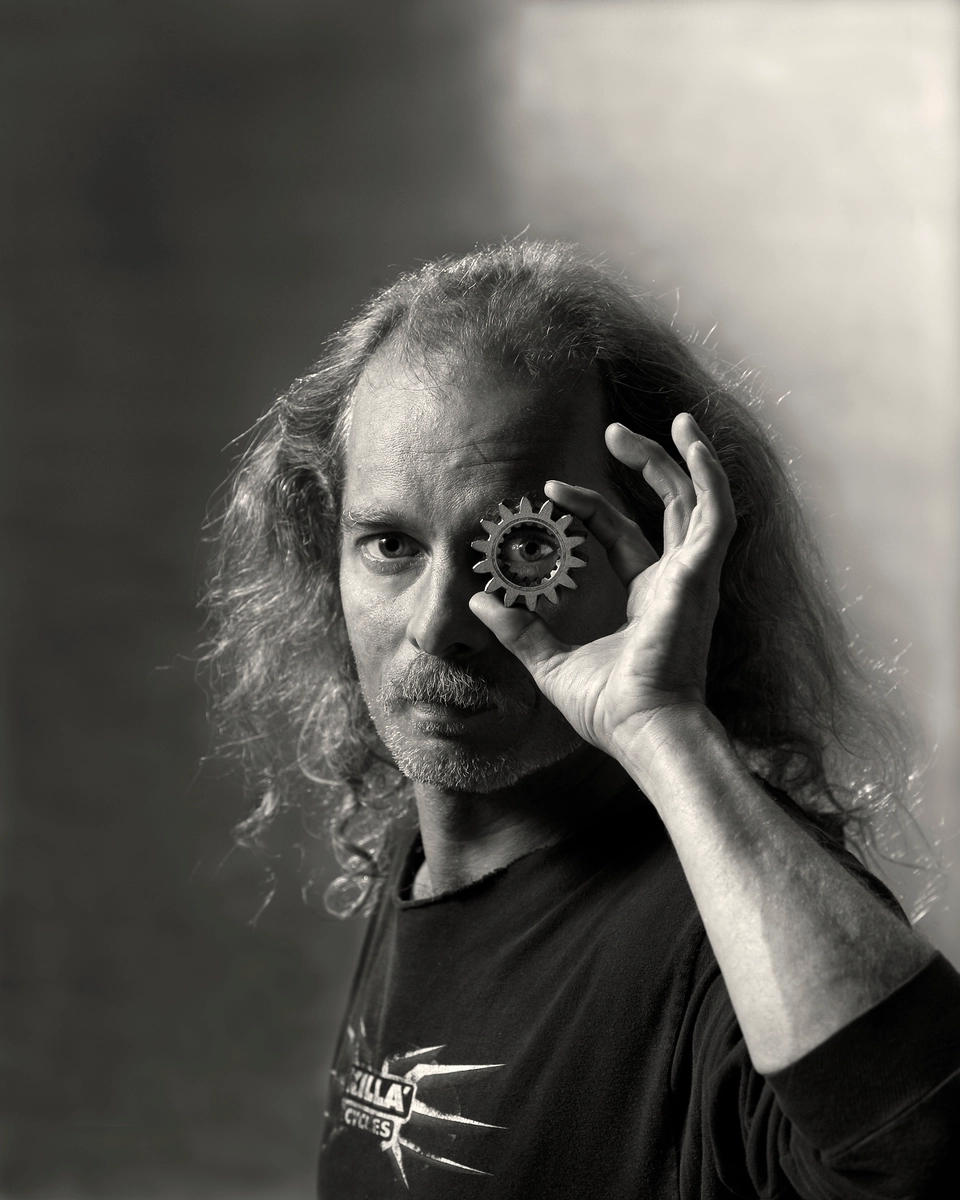

Kirk Taylor © Tom Zimberoff

Six years later, I got a phone call from a woman named Deborah Roundtree from Little Rock, Arkansas, who told me she had enjoyed reading my

Art of the Chopper books and, in her capacity as Exhibits Specialist at the William J. Clinton Presidential Library & Museum, wanted to know if I could gather the actual motorcycles I had photographed from all over the world for an exhibition. The idea was to spotlight an art form as indigenous to America as jazz, what I’d begun calling

haut moteur. She introduced me to the Clinton Library curator, Christine Mouw, who invited me to co-curate an installation.

Praise the lowered! The show opened on September 20, 2008, with a gala reception, but the former president was away. We displayed thirty motorcycles that had been illustrated in my books, mounted on pedestals, and juxtaposed with my portraits of the artists who built them. The photographs were hung on adjacent walls and freestanding panels. When the exhibit closed five months later, it traveled to the Appleton Art Museum in Ocala, Florida, then Union Station in Kansas City, Missouri. In Kansas City, we built a full-scale diorama of a motorcycle shop inside the gallery, replete with an unfinished motorcycle sitting on a hydraulic lift, a politically incorrect calendar on the wall, tools strewn every which way, and a simulated (plastic) oil spill on the floor that looked real enough to have been an accident, flowing from the “shop” into the main gallery. It was fun to watch visitors step over and around it.

The exhibition had nothing to do with my first and only meeting with Bill Clinton at Pier 23. It was purely coincidental. He had known nothing about

Art of the Chopper until it opened to the public. But I like to imagine the former president, who kept a residential apartment above the Library, sneaking down at night in his pajamas to sit on one bike after another.

Haut moteur is to motorcycles as haute couture is to apparel the

dernier criof extravagance. With each new season, the most influential elements of one-off couturier gowns with price tags as jaw-dropping as their scintillating sophistication go from runway to rack, precipitating retail fashion trends. So, too, do over-the-top handmade motorcycles kickstart a process of trickle-down style wending its way to mainstream machines on the showroom floor. However, instead of sylphid supermodels dressed by Chanel, Dior, Balenciaga, Versace, and Van Herpen prancing down the catwalks of New York, Paris, Tokyo, and Milan, picture the mean streets of Sturgis, South Dakota or Daytona Beach, Florida and a gaggle of bodacious bodybuilders astride the latest creations from Goldammer, Hotch, Nasi, Ness, and Perewitz.

These are choppers.*They debut seasonally at rallies throughout the country like a peripatetic Fashion Week. Only a few connoisseurs among the throng of spectators watching these phantasmagorical motorcycles parade up and down the main drag have the economic clout to ride home on the real deal, to buy an original, that is, instead of a knock-off. But their patronage propagates chopper style throughout the world, allowing an elite coterie of artists, haut moteuriers if you will, to reach new milestones of creativity, transforming an unruly congress of chrome, oil, rubber, pig iron, paint, and decibels into the high art of the low rider.

* Just for the record, the people who naively started using the word chopper to describe a helicopter were TV and radio news reporters reading from teleprompters, who thought they were being clever. Pilots call them “helos.”

Mad Rat by Jerry Graves © Tom Zimberoff

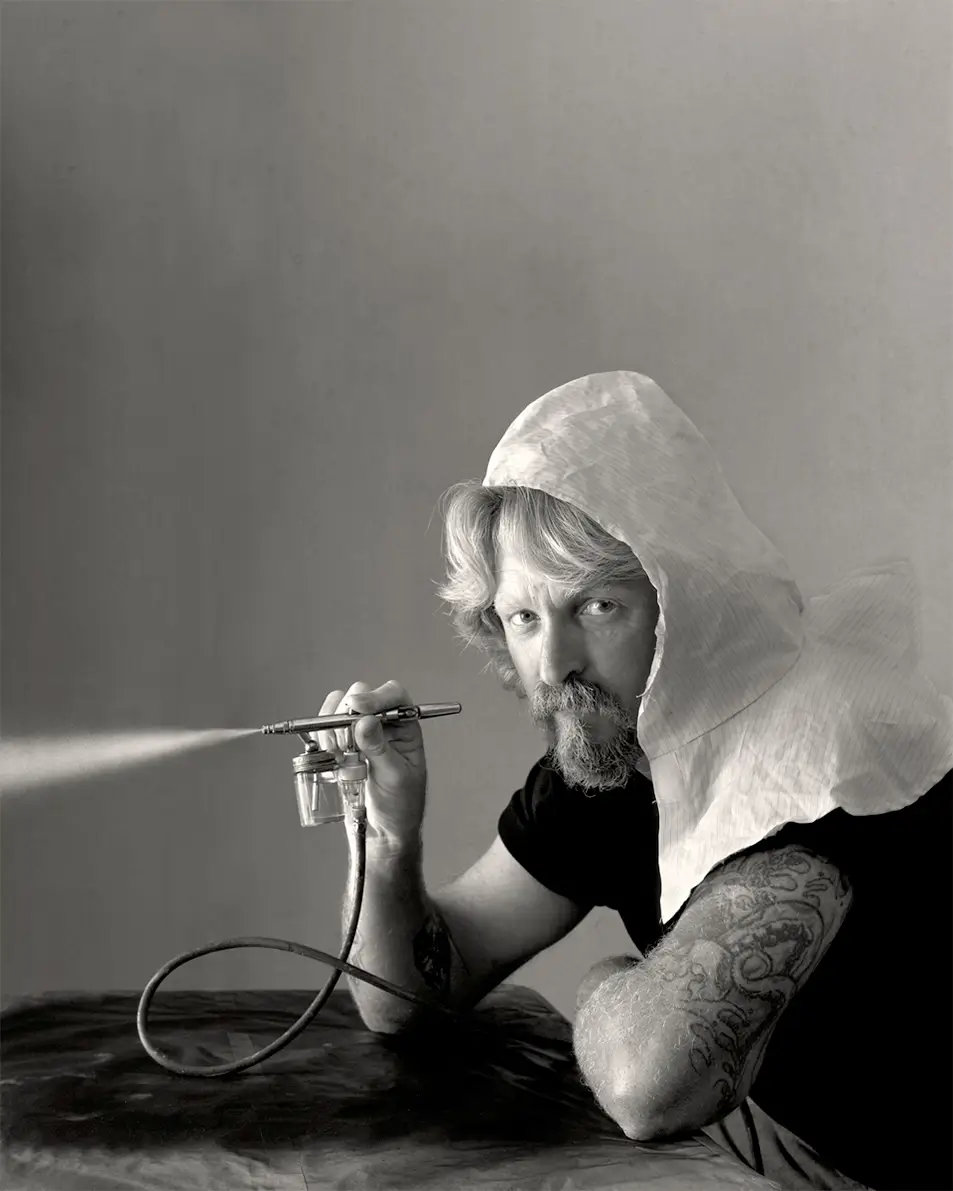

Jerry Graves © Tom Zimberoff

Worldwide, only a few dozen moteuriers practice at this level of innovation and savoir-faire, creating highly conceptualized handmade machines, quite literally vehicles of self-expression that balance flamboyance and minimalism on two wheels. They are at once both garish and sublime. To say a chopper looks “trick” or “sick” implies a chassis that vaunts more curves than Beyoncé in a bustier, a shift lever on the trajectory of an intercontinental ballistic missile, or with exhaust pipes and carburetor stacks jutting out from its engine like the paraboloid brass bells bells of cornets in a marching band belting out a fortissimo fanfare. These bikes are all wound up, so hang on to your helmet! Yet, for all the hooptie, they are as rideable and safe as any ten-foot-long motorcycle can be.

Generally, a motorcycle’s organs and circulatory system are exposed, supported by an exoskeleton of aluminum and steel. But for every one with its guts protruding hither and yon, you’ll find another with all but the essentials tucked away, hidden. Of course, you can always see the engine — the motor; that’s a given. But some artists, employing feats of mechanical prestidigitation, play hide-and-seek with critical components to make their choppers look as implausible as they are visually beguiling. Bereft of a whole slew of motorcycley things one expects to see, it makes one wonder what makes it go. Where are the wires, the levers, the switches, the cables, the suspension system, and other eyefuls of distraction? Some moteuriers can even make axles seem to disappear. They will leave nothing visible to detract from a smooth graphic outline that frames the motor. Such examples are fetishized for looking “clean.”

Enthusiasts have long enjoyed visiting “bike shows.” There are now audiences for this phenomenon in Europe and Asia, as well as in the United States. Motorcycle shops all over the world vie for trophies, not for speed but for visual appeal. The elevation of the motorcycle as art, however, first gained credibility in 1998 with an exhibition appropriately called “The Art of the Motorcycle” at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City. It toured Las Vegas, Chicago, and Bilbao, in Spain, attracting three million paying visitors. That is compelling proof that an irrepressible desire to present motorcycles as art corresponds with the public’s demand — including non-riders — to see them. That installation, the first to present motorcycles as objets d’art, is rivaled in attendance by few other museum blockbusters. Not even “The Treasures of Tutankhamun” attracted more visitors.

Despite the popularity of the Guggenheim’s take on motorcycles, some critics doubted that such a “utilitarian” thing belonged in an art museum. Perhaps they saw the line connecting motorcycles to art as coming up short because the Guggenheim hadn’t set out to acknowledge individual artists. They aimed, instead, metaphorically, to represent the evolution of twentieth-century industrial design by presenting a collection of motorcycles intended for conveyance, not necessarily aesthetic delectation, and by arranging them chronologically.

All but two of the one hundred and fourteen motorcycles on display were intended for commercial production. The two outlier bikes, one mislabeled as a Harley-Davidson and the other as an Indian, were the only choppers, ones of a kind, not production bikes. They were mislabeled because they bore scant resemblance to their Harley and Indian origins, having been transformed by three artists whom the Guggenheim’s curators did not publicly acknowledge. Such mislabeling was like attributing a masterpiece to the company that manufactured the canvas it was painted on. In fact, no individuals at all were acknowledged for their artistic contributions to these motorcycles; only the brand names, the marques, were celebrated.

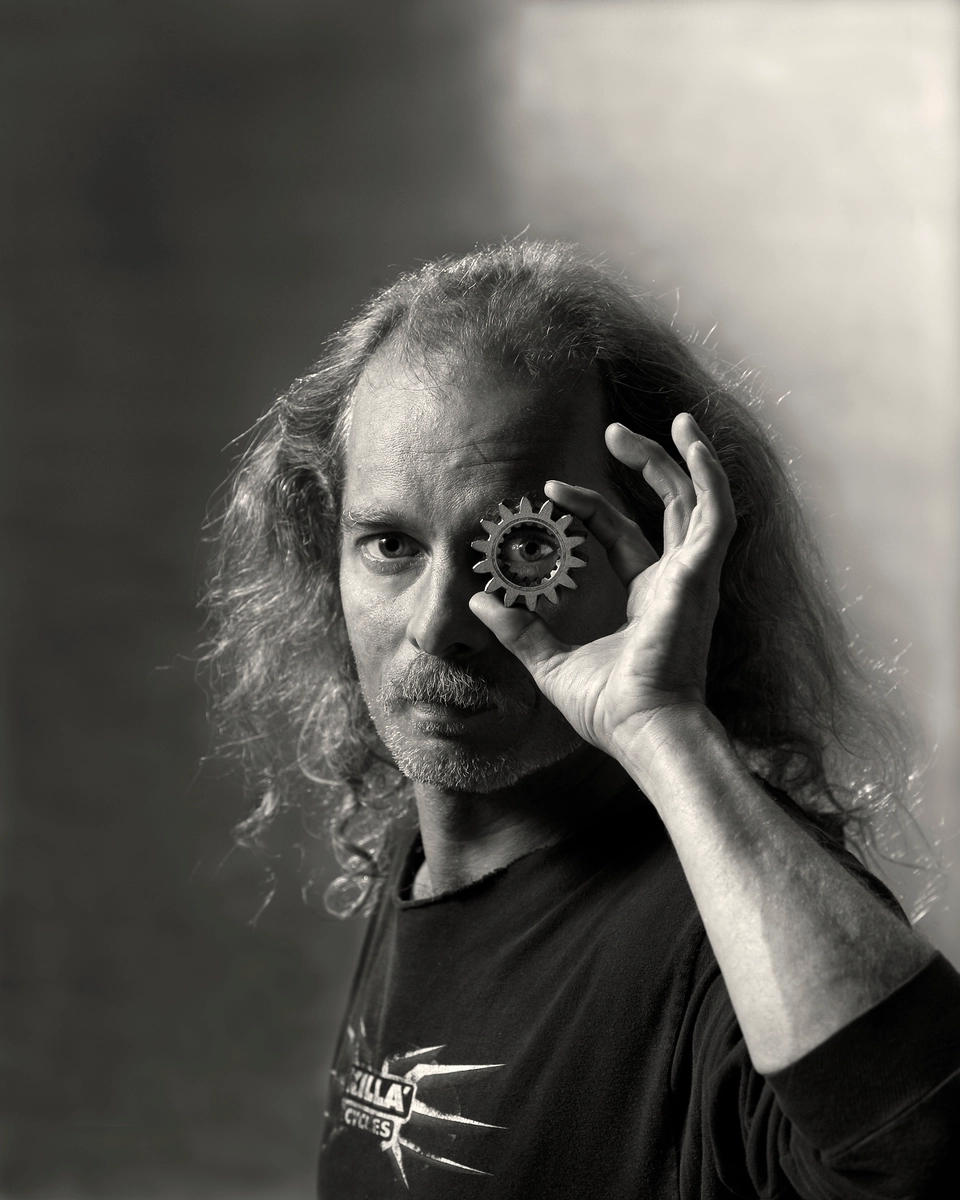

Fred Kodlin © Tom Zimberoff

Ford Stell © Tom Zimberoff

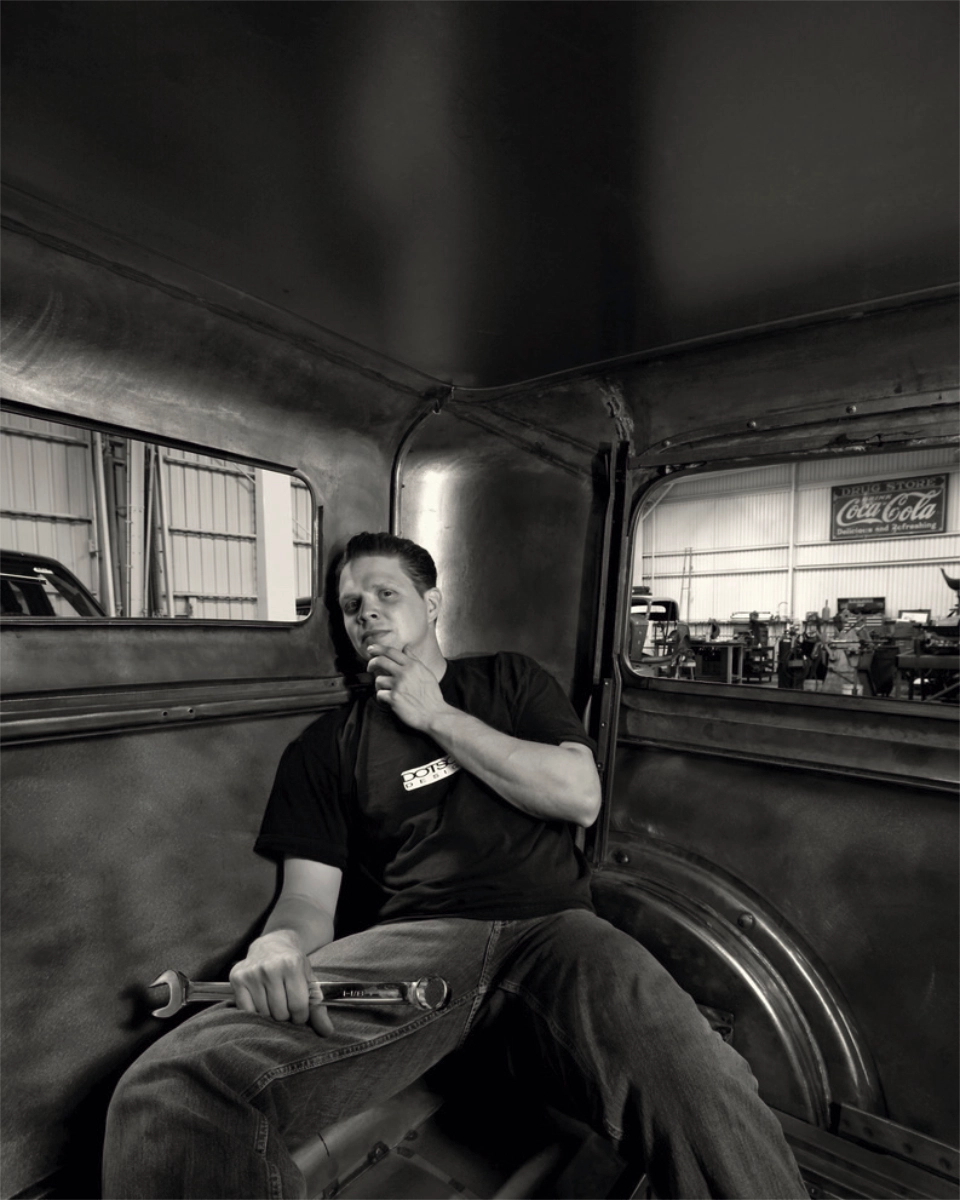

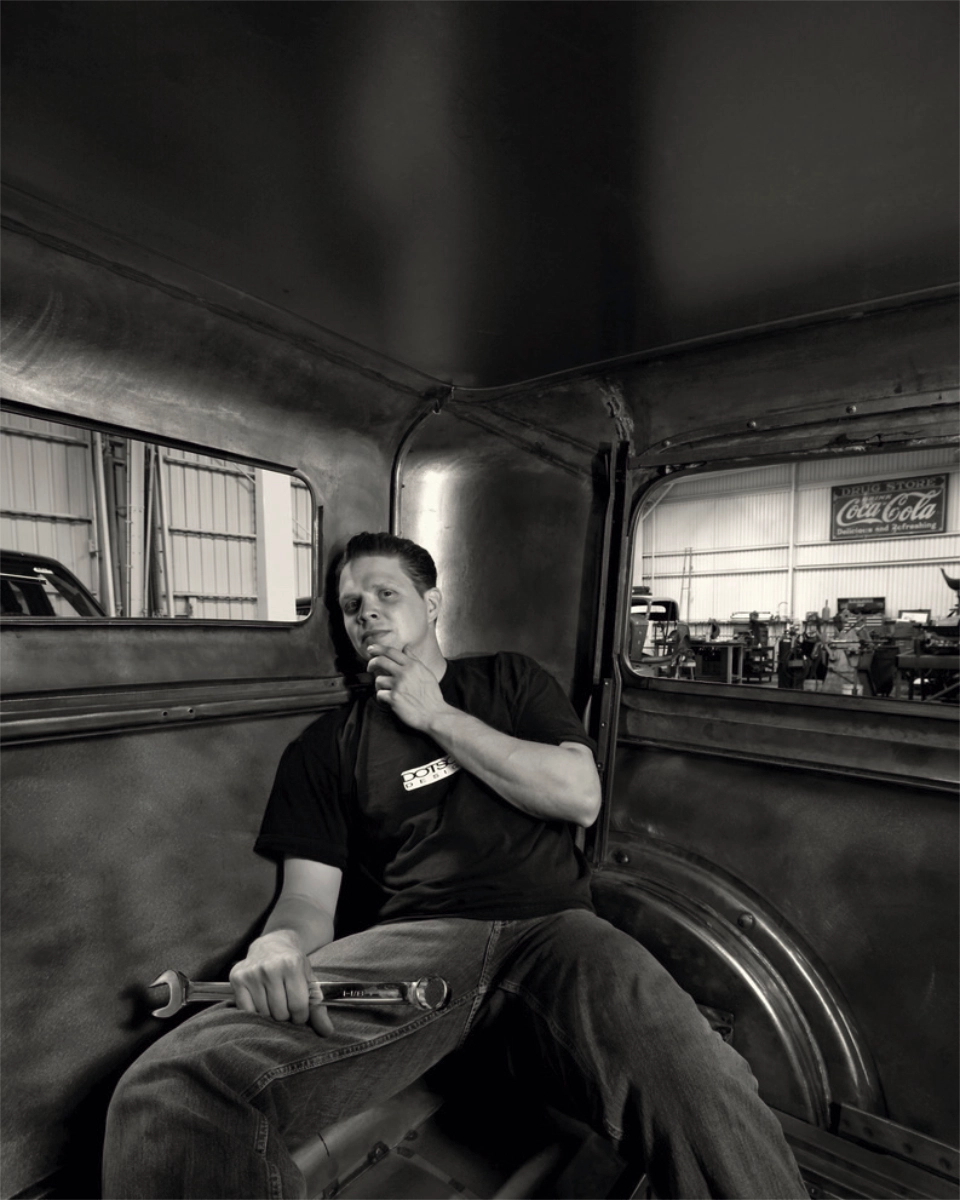

Christian Dotson © Tom Zimberoff

To clarify, the Guggenheim’s

Hardly-Davidson was merely a replica of the original “Captain America” chopper built by the late Ben Hardy for the classic 1969 movie

Easy Rider. Hardy’s cultural contribution went unrecognized by the curators. The only thing about that motorcycle that came from the Harley-Davidson factory was its engine. Everything else was first imagined and then handmade by Mr. Hardy. The authentic

Hardy-Davidson was stolen before the movie was released, no doubt “parted” (dismantled) for the black market. No one remembers or cares who built the copy — a slew of them exist. The putative Indian was originally a 1940 U.S. Army 640B model. It was transmogrified by Jerry Greer and John Bivens in 1996.

Inspired by the Guggenheim’s success, I wrote and illustrated

Art of the Chopper, then a second volume. I staked out my own approach to presenting motorcycles as art. Mine was more forthright because none of the examples I cited was a

fin de siècle prototype or a later design slated for assembly-line production. Not one motorcycle in

Art of the Chopper represents a commercial marque. I exclusively selected one-of-a-kind motorcycles created by seminal artists whose work, although often copied by commercial manufacturers, is readily identifiable on the street by style alone.

All motorcycles have two wheels, a frame, a seat, a gas tank, plumbing, controls, and an engine. But choppers are made from parts that no longer look like they were initially designed, parts used in oddball ways, and parts that never existed before. Mereologically, they confound orthodox ideas about form and function because, when the whole is indeed greater than the sum of its parts, having become interdependent and reliant on each other existentially, it becomes art.

The improvised riffs of chopper builders have given rise to as many mechanical doodads, chrome thingamajigs, handlebars, frames, forks, pipes, tanks, and tires — and different ways to combine them — as there are notes in a Charlie Parker saxophone solo. Also like jazz (and rock 'n' roll), chopper design is cross-culturally pollinated by devotees throughout the world. The best examples, despite having much in common, are unique. Each chopper is a motorhead’s haiku, a succinct expression of biker poetry in motion.

Proponents of chopper style express the idea that “less is more” by, well, chopping something off of a perfectly good motorcycle. The impetus to do so stems from making bikes lighter and faster for racing. It then evolved into a more imaginative construct, earning admiration for good looks alone. In other words, what got taken off was replaced by putting something else back on, something more fanciful. Think of replacing a petcock (a gasoline-flow on/off switch) with a porcelain hot water spigot from a 1930s bathtub (e.g., Billy Lane), velocity stacks (carburetor air intake) with barroom shot glasses (e.g., Alan Lee), or substituting a seventy-five-year-old ampere gauge from a tugboat — steampunk style — for a speedometer (e.g., Shinya Kimura).

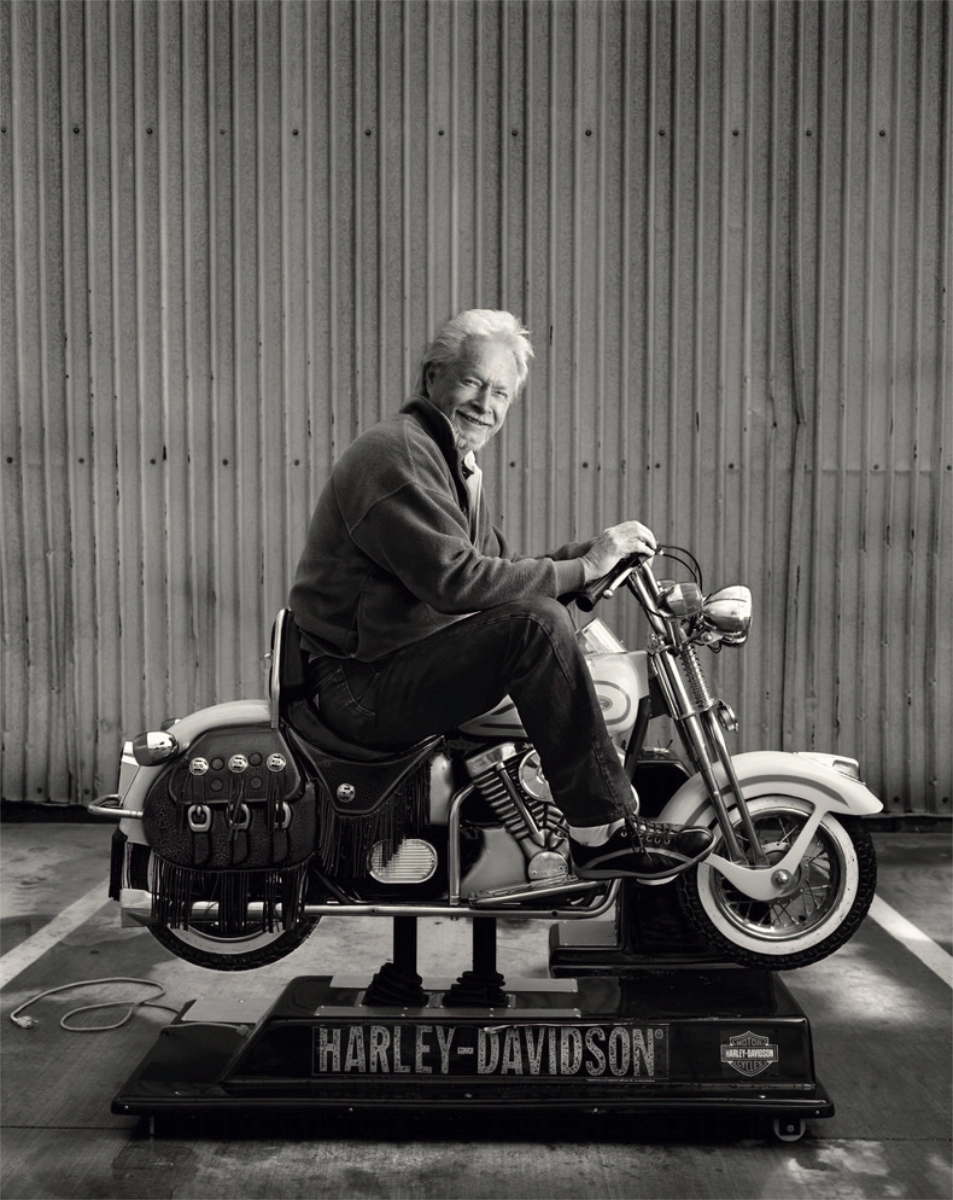

Arlen Ness © Tom Zimberoff

Two Bad by Arlen Ness © Tom Zimberoff

Some choppers are deliberately bereft of a front brake. That would be a problem if you tried to stop on a hill, facing up, because your left foot would be on the clutch, in gear, and your right foot would be stomped down on the rear brake pedal while your left hand palmed the shifter. Catch my drift; both feet off the ground, one hand on the bars? Not happening. In hilly San Francisco, your buddy had your back — literally. His bike was your brake. It was stopped behind yours, its front tire to your rear tire, so you could plant your brake foot on the ground. That’s how bikers used to roll.

If necessity is the mother of invention, extravagance is its stepmother. It means getting something wrong just right. Whether an artist starts with a new bike or an old one — or from scratch with nothing but sheet metal, steel tubing, and billet blocks of aluminum, the result will be something no one has ever seen before. By contrast, modified cars, or hotrods, are imbued with designs that can hardly be disguised. Despite being customized, they’re still recognizable as Chevys, Fords, and Dodges. A moteurier, however, can pull something out of his hat that bears little resemblance to an existing brand. It may or may not adhere to the Harley motif — there are Triumph, Yamaha, Honda, and Ducati choppers, too — but there is indeed Harley-Davidson DNA in every chopper. The rhythmic rumble of a fire-breathing, V-twin Milwaukee mill waiting at an intersection for a red light to turn green is the original “American idle.” Or American

idyll.

In Kirk Taylor’s shop, shooting pictures for

Art of the Chopper II, I struck up a conversation with someone wrenching on a bike whom I took to be Kirk’s employee. Our topic turned to music, specifically heavy metal — not my favorite. But I was intrigued by this guy’s erudition. I told him my pictures of Kirk’s shop were earmarked for my book about motorcycles. He wiped some grease off his hand and extended it. He said his name was James and asked if he could be in the book. It seemed like an odd question. Trying not to be patronizing, I explained how he might appear in the background of one photo or another if it survived the editing cull.

Standing behind me, Kirk was eavesdropping, trying not to laugh. When he could contain himself no longer, he told me that James was James Hetfield of Metallica. We agreed to feature his new chopper in the book, the one he was working on, designed by Kirk. It was the one he was paying so much attention to. I asked James if he would write the foreword. He did.

Satisfying as it is to see these motorcycles exhibited in a museum, the chopper ethos demands that they be ridden, not parked too long on a plinth. Choppers are kinetic , the epitome of performance art. And it takes an exhibition-ist to pull that off, someone armed and hammered by his own hauteur or the swank of haut moteur. Women wear high heels; men ride choppers — same thing. Yeah, there’s some crossover. But the point is: “It’s better to look good than feel good,” as builder Eddie Trotta will tell you.

When you sit astride a chopper, you are the center of attention, whether it’s rolling or not. A bespoke chopper, tailor-made to accommodate its owner’s inseam, the reach of his arms, and the size of his hands will amplify the effect. By contrast, the Harley-Davidson Motor Company refers to a so-called “custom bike” as something that might be called a “billet barge” * or a “Milwaukee vibrator” in the argot of chopper riders. Only somewhat less derisively it’s called “catalog customizing.” Indeed, Harley owners spend big bucks to make their rides look special with allegorical paint jobs and bolt-on gewgaws. But you can only go so far as to make one bone-stock bike look different from every other rider’s pride and joy. A motorcycle isn’t custom-made just because it’s shiny enough to catch the glint of the sun and be seen from the International Space Station. Stock Harleys bedizened with gleaming chrome and gaudy paint jobs are merely custom-

ized. That’s synonymous with personalized. They are attention-grabbers, for sure, and fun to ride, but to chopper riders they’re one taco short of a combination plate.

Sophisticated riders of choppers and customized bikes alike appreciate the loud bark and stereophonic timbre of a V-twin motorcycle stripped of everything but what it needs to go fast, stop fast, and look good. In an atmosphere redolent of hot iron and motor oil, the syncopated patter of pistons on a flywheel —

potato-potato-potato-potato-potato — is music to my ears, an internal combustion concerto.

(*

Billet refers to blocks of bulk aluminum that can be sculpted using a computer-controlled 3-D lathe to become add-on performance parts and cosmetic accessories. When polished to a high sheen, it is often mistaken for chrome.)

Art of the Chopper Theme Bike by Various Artists © Tom Zimberoff

Billy Lane © Tom Zimberoff

Spike by Shinya Kimura © Tom Zimberoff

Holy Roller by Mike Brown © Tom Zimberoff

Eccentricities aside, these are minimalist machines. They don’t appeal to riders of “full-dress hogs” with windshields, saddlebags, and stereos. Shoot me dead if you see me on a bike like that. And shoot me if you ever see me wearing chaps. Alright, I’m overreacting. It’s just another culture, another aesthetic. But chopperators ride badass machines and would rather not see someone else’s bad ass sticking up in the air on a “crotch rocket.” There’s nothing sexy about riding in the fetal position. “You may meet the nicest people on a Honda,” spoofs Kirk Taylor, “but it ain’t gonna get you laid!” I will add: neither will popping wheelies wearing a $700 helmet that will soon sport some brutal skid marks. Those riders, a.k.a. “squids,” will ultimately get scraped off the road. Their YouTube videos will be linked posthumously to memorial websites. By the way, Taylor, who personally paints the choppers he builds, prefers subtle pin-striping over $15,000 worth of demonic skull warriors ornamenting a gas tank, and he has always been a fan of metal-flake and flame jobs that he calls the “dune-buggy and drum-set look of the 60s.”

There is little about art that complies with motor vehicle codes. By virtue of its best points, a chopper will flout at least a dozen state and local laws, speed limits notwithstanding. Choppers are bereft of turn signals, horns, gauges, mirrors, idiot lights, and rear suspension. Instead, they bristle with racing motors, loud pipes, ape-hangers, sissy bars, velocity stacks, and whatever adornments a builder sees fit to flaunt. Pass an emissions test? I don’t know. But I do know many legally-licensed vehicles that won’t. Neither will your backyard Weber grill. Barbecues foul the air more than all the motorcycles on planet Earth put together. But choppers are the only real outlaw bikes, and there will always be authorities with little tolerance for them. However, as often as not, cops let the finest examples roll by with a wink and a nod because they ride, too.

Incidentally, the first photographs of choppers I remember seeing appeared in Look magazine: Irving Penn’s portraits of Hells Angels posing with their Harleys in a studio, part of a 1968 feature about San Francisco’s counter-culture. Then, In 1969, also in Look, I saw a young Ann-Margret hurtling down a two-lane ribbon of desert backroad on a perfect red, stretched Triumph chop with tank scoops and a girder front end. She wore a stars-and-stripes bustier that mimicked Peter Fonda’s characterization of Captain America that same year in

Easy Rider. The photograph was made by Douglas Kirkland, a mentor who helped me kickstart my career.

Since then, I have committed to shine a light on — and point a camera at — custom motorcycles to help them survive for future generations to enjoy. I want to keep the best examples from ruin through neglect or deliberately being taken apart, their gestalt destroyed by removing dedicated components and glomming them onto unrelated motorcycles. I don’t want to see an artist’s original vision desecrated by a third-party owner with a fickle eye for a new paint job or mismatched handlebars. I want to see them conserved, not ridden into oblivion. A chopper should be considered the immutable expression of an artist whose vision exists within a continuum of aesthetic and cultural evolution.

In light of that, the concept of haut moteur should come as a breath of fresh exhaust. So smile at that show-off; don’t show him (or her) the finger. Go to a bike show! Peer into a parallel universe populated by horsepower-addled, lane-splitting libertarians, hell-bent for leather on the road to perdition with a lust for life and a consummate sense of style.

Indian Larry © Tom Zimberoff

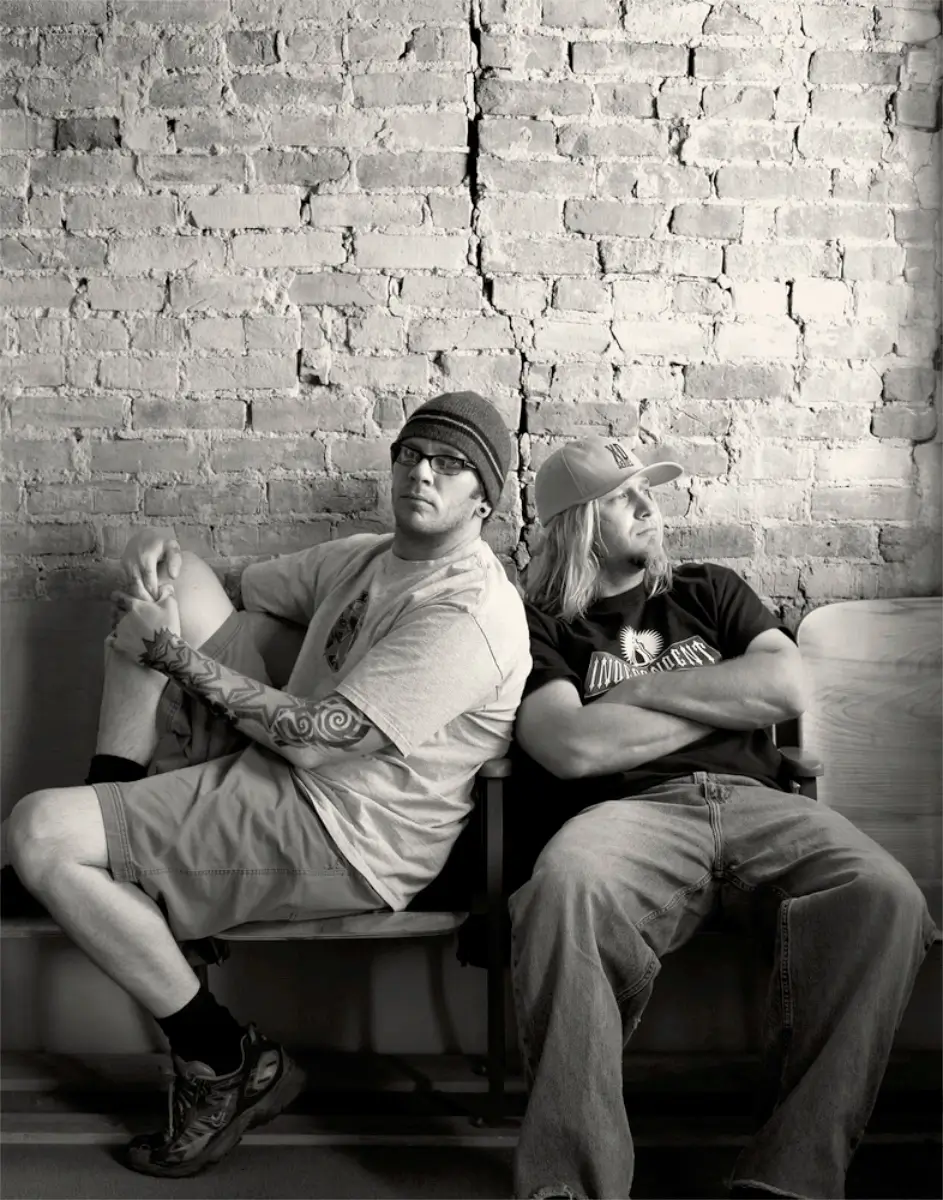

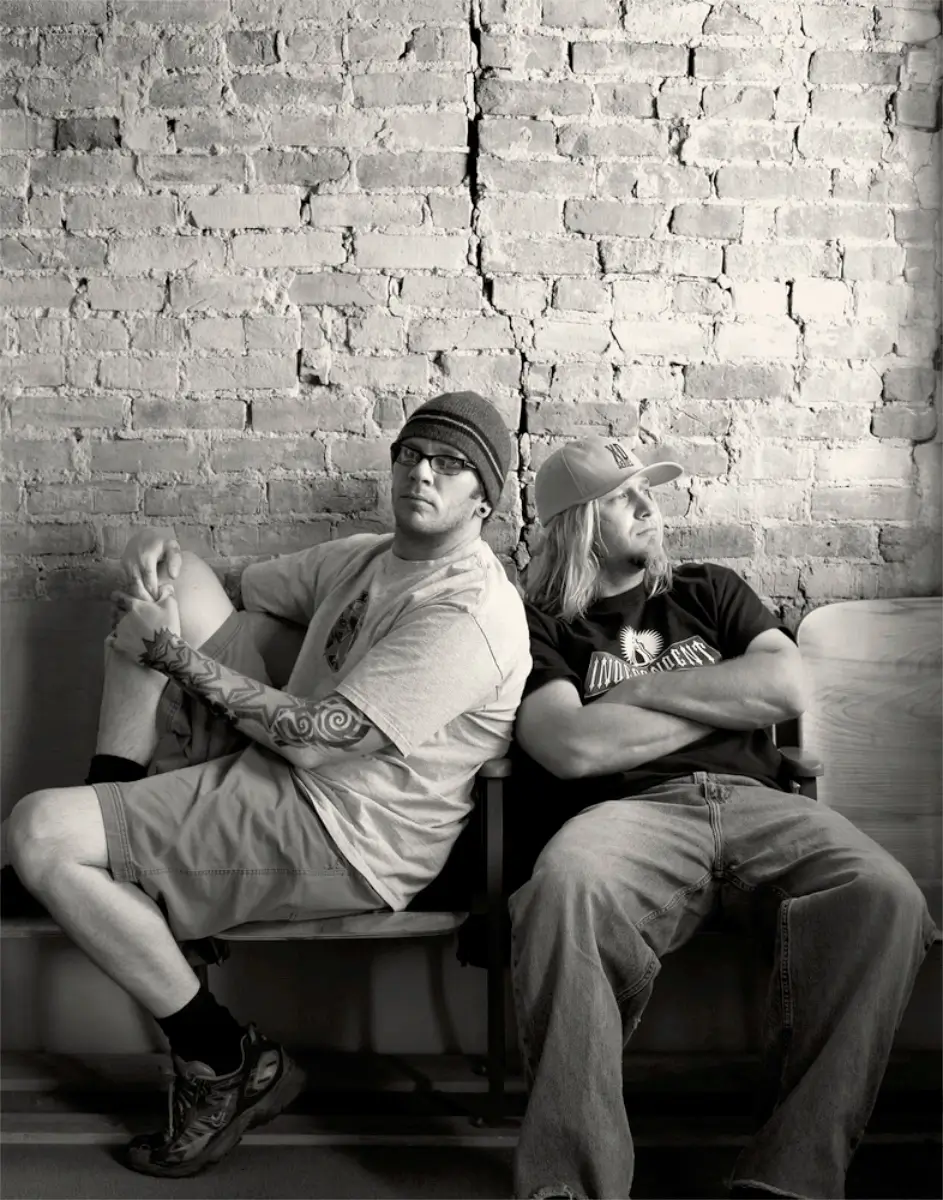

Jesse Jurrens & Michael Prugh © Tom Zimberoff