From July 13 to November 18, 2024, the

Centre Pompidou-Metz is featuring

photography in all its forms in the exhibition Seeing / Time / In Colour.

It is curated by leading photography specialist Sam Stourdzé, who is currently

director of the Villa Médicis in Rome and was formerly director of Les

Rencontres d’Arles from 2014 to 2020 and the Musée de l’Élysée in Lausanne

from 2010 to 2014. The exhibition brings together around 250 works and

50 photographers, offering a unique overview of the major technical challenges

that have marked the history of the discipline. It will provide an opportunity

to discover exceptional works: from very rare plates showing the restoration

of masterpieces from the Italian Renaissance to rarely exhibited seascapes

by Gustave Le Gray and autochrome plates from the collection of Albert Kahn

recreated for the exhibition.

Optical and mechanical features, chemical procedures, innovative physical

properties: for a long time, technology was lumped together with the objective

sciences. However, more than just a simple means of photographic production,

its developments have paved the way for, or given rise to, all of its most

important artistic revolutions.

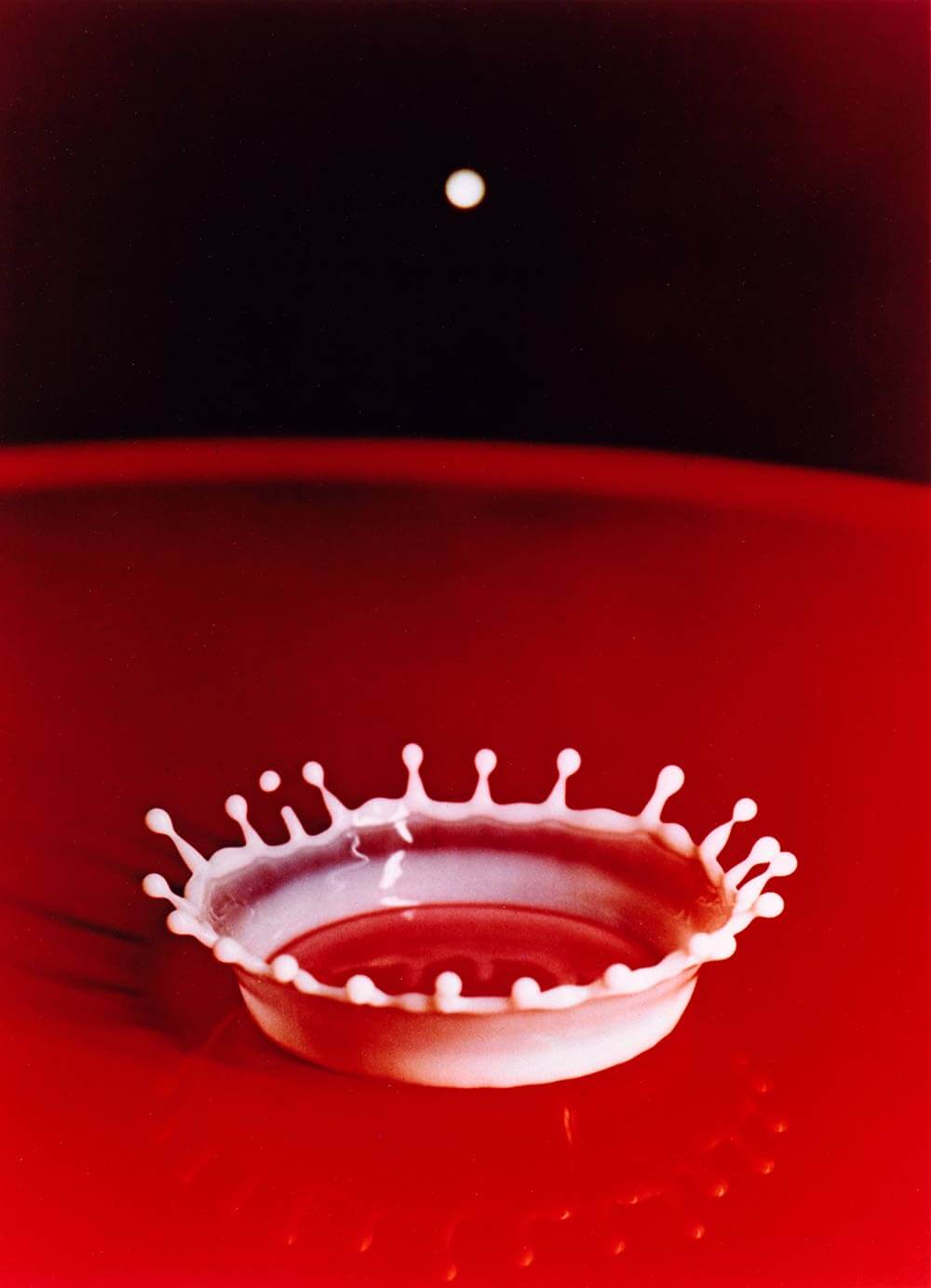

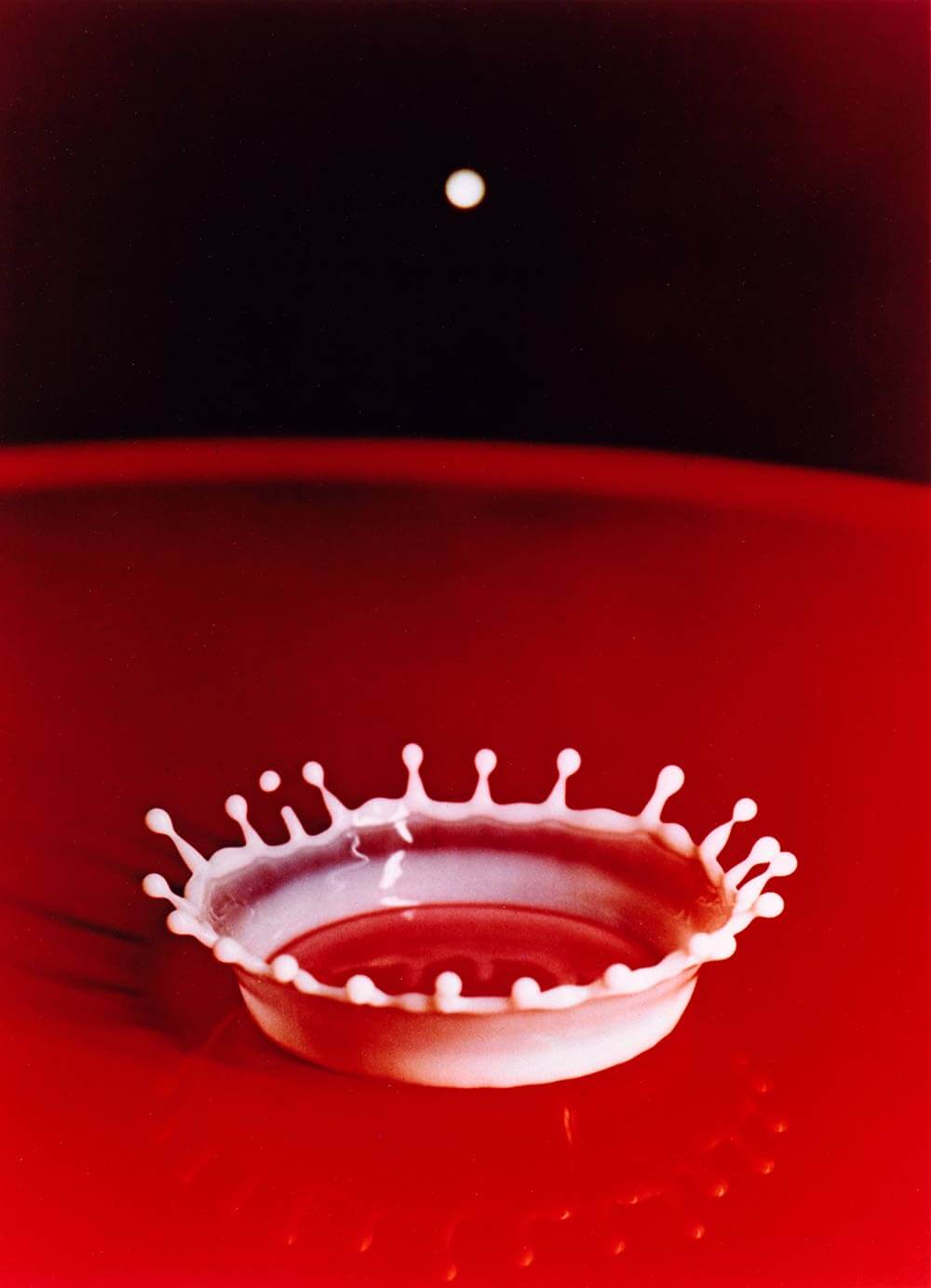

Harold Edgerton, Milk drop coronet, 1957, 50,8 x 40,64 cm épreuve dye-transfer Collection Arlette et Gus Kayafas © Harold Edgerton/MIT, courtesy Palm Press, Inc., from the Kayafas Collection

Divided into three sections, the exhibition examines key issues connected with

the reproduced image, the origins of photography, the rise of the snapshot, which

enabled the discipline to be considered “modern”, as well as its relationship

to colour, a pivotal development that led to an unprecedented democratisation

of the practice. In each of these three sections, the photographic work of a

particular iconic figure will be showcased: Constantin Brancusi, who hijacked

the reproductible function of the image in order to produce hundreds of

photographic interpretations of his sculptures; Harold Edgerton, who, in the

1950s, fixed time in the image eventually causing it to break down; and Saul

Leiter and Helen Levitt, pioneers of colour photography who through their use

of areas of colour transformed reality into a poetic form. Around these figures

will emerge a multitude of other artists who have explored unknown facets of

photography.

Interweaving periods, the exhibition will bring together the pioneering works of

19th- and 20th-century photographers and those of contemporary artists, from

Hans Peter Feldmann, who revisits the camera obscura with his installation

Shadow Play as an inaugural form of the reproduced image, to Dove Allouche,

Ann Veronica Janssens, Laure Tiberghien and Hugo Deverchère, whose works

highlight, throughout the exhibition, the many paths that are still being opened

up, even today, by the technical manipulations of the medium.

Infinite reproduction

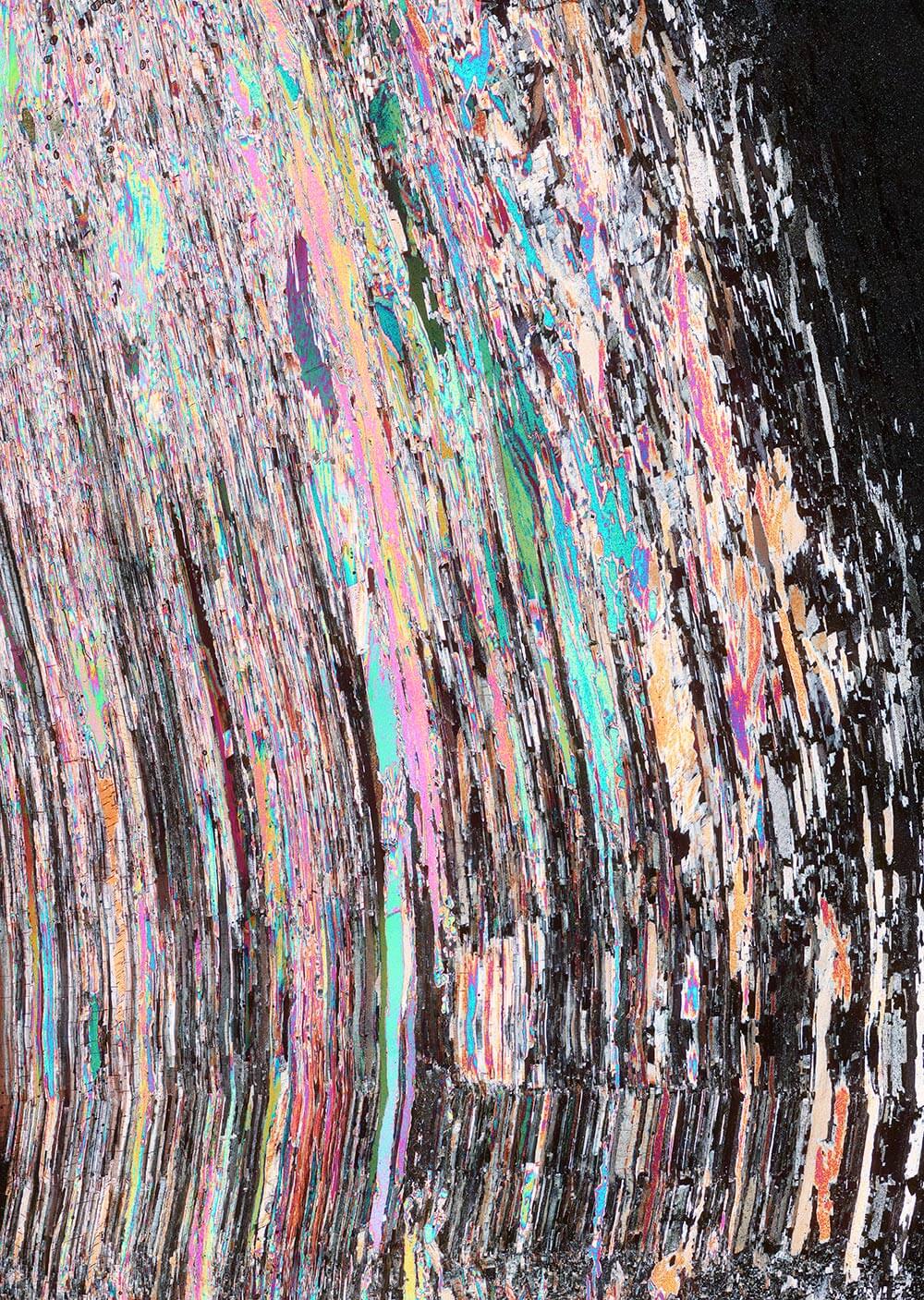

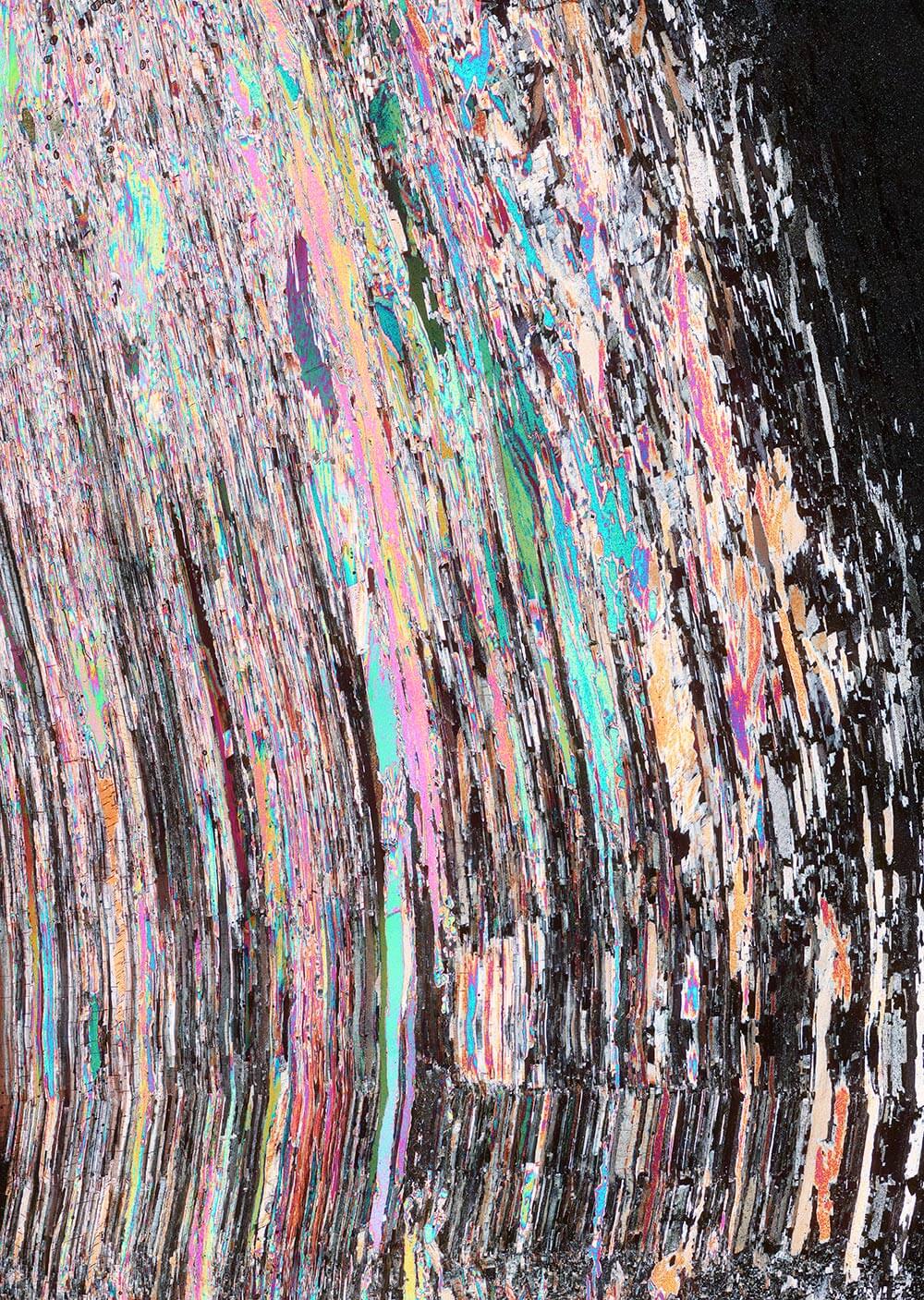

Dove Allouche, Evaporite_19, 2019 Tirage argentique Lambda d’après une lame mince prélevée sur un bloc de gypse, 175 x 125 cm Paris, collection particulière © Photo Dove Allouche

The historic essay written by Walter Benjamin in 1935, The Work of Art in the

Era of Mechanical Reproduction, laid the foundations for the great challenge

posed for all of the arts of the 19th century by the emergence of photography:

the possibility of immediate and infinite reproduction undermined the work

of art’s unique sacred status. Although the concept of reproduction is central

to the photographic process, artists have continually sought to reinvent it,

formally and conceptually. Constantin Brancusi, the first great figure in the

exhibition, photography was not a way of documenting his works, but rather

an embodiment of his thinking about his sculptures. The multiple views that he

made of his works in the studio reveal his interest in mise en scène, in which

no detail was left to chance, from the position of the base to the lighting and

the choice of background colours for controlling the light.

From the outset, photography was used as a way of objectivising reality.

By making accessible what had up until then eluded the realm of observation,

it turned out to be a unique tool for documenting, disseminating and

encouraging the great conquests of modern western history. Thanks to the

Bisson brothers, who took nearly a thousand panoramic views of mountain

chains between 1858 and 1862, the mountain and its peaks, previously hostile

or simply unknown places, were now within reach of the image.

In parallel, astronomical views multiplied, notably under the impetus of the

Henry brothers, who in 1884 produced the first map of the sky, and took

numerous photographs of planets, stars and astronomical phenomena, which

were widely distributed among the scientific community and the general public.

In this respect, the iconic photographs of Nasa’s space conquests in the 1960s,

rarely shown in France, are a reminder of the extent to which photography

structures our imaginations as much as it serves a political objective. Another

conquest, that of the realm of the infinitely small, saw photography supplant the

microscope. Little by little, it left the realm of the sciences and became a form

of visual experimentation, epitomised in particular by the photographer Laure

Albin Guillot who in 1931 unequivocally renamed it “decorative micrography”.

Encapsulating time

Gustave Le Gray La Grande Vague à Sète, n° 17, 1857 Photographie sur papier albuminé Collection du Musée barrois, Bar-le-Duc. Inv. prov. 14.01.30.1 © Musée barrois / N. Leblanc

The most radical transformation in photography was the mastery of the snapshot,

achieved for the first time in 1841 with the first negative/positive process in

history. In 1856, thanks to a much shorter shutter speed, Gustave Le Gray was

able to take his famous Seascapes [Marines], photographic landscapes of

oceans captured on the spot and whose picturesque aesthetic adopted the

conventions of landscape painting. With the arrival of the snapshot, our entire

relationship to the tool was transformed: photography was no longer simply a

means of obtaining an image that was planned in advance, but rather an end

in itself, leading to a dizzyingly infinite number of possibilities. There remained

one challenge for it to overcome: in order to capture a dense, cloudy sky, the

sea had to be under-exposed, thus appearing too dark; in the opposite case,

the sky, over-exposed, would disappear. To get around this, Gustave Le Gray

produced the first manipulated images, the first photomontages in history, by

combining one negative for the sea with another for the sky. He thus obtained

a perfectly density, from sea to sky.

In the context of the technical modernity of the late 19th-century, glorified by

speed, the exactness and precision of these new processes paved the way for

a variety of experiments. In the United States and France, the pioneering work

of the physicists Eadweard Muybridge and Étienne-Jules Marey transformed

our understanding of human and animal physiology.

With the chronophotograph, invented by Étienne-Jules Marey in 1882, it was

possible to record a series of successive images, taken at a thousandth of a

second, on a single surface, thus revealing the imperceptible trajectory of bodies

in movement. The revolution extended well beyond the realm of photography,

serving the visual arts – it preceded by nearly 30 years the experiments of the

Futurists, and opened the way to proto-cinema – as well as medicine and the

physical and natural sciences.

Artists and scientists worked together to push back the limits of the visible.

Harold Edgerton, a professor of electrical engineering at the Massachusetts

Institute of Technology (MIT), used his stroboscopic flash device to push

the photograph to its furthest limits. The falling drop of milk he managed to

capture, at the precise second when it hit a flat surface, reflected his desire

to expose the passage of time. He became obsessed with this quest, devoting

two decades to it, from the first crown formed by a splash that he produced in

1936, to the brightly coloured version in 1957, which is striking in its immense

visual clarity. Here, at last, was one of photography’s great achievements:

encapsulating time.

Fixing colour

© Léon Busy pour “Les Archives de la Planète”, Tonkin, 1915 Autochrome, 12 x 9 cm, Boulogne-Billancourt, Musée Départemental Albert-Kahn

The ultimate challenge was to capture colour. As testified by the humanist

utopia of the banker Albert Kahn, who wanted to create an archive of the

planet, colour was initially the preserve of scientists, from the pioneering

experiments of Louis Ducos du Hauron, who took the first colour photograph

in history in 1877, to the dazzling success of autochrome plates in the first

quarter of the 20th century. In the 1930s, with Yevonde Middleton, a pioneer

of colour photography in England, it acquired burlesque, eccentric and, for

the first time, feminist aesthetic qualities. Thanks in part to Saul Leiter, one of

the greatest colour photographers, it became a photographic style in its own

right. He declared: ‘Painting is glorious. I love photography, but I’m not sure

photography can do what painting can.’ And yet, he rendered in colour what

few had managed to convey before him. Playing with large areas of colour

and often monochrome palettes, Leiter worked colour in a body of work that

anticipated Helen Levitt, William Eggleston, Joel Meyerowitz and Stephen

Shore, even though, paradoxically, he was only celebrated for his achievements

after them.

Seeing / time / in colour: three periods when technological advances made

it possible to capture on paper the great achievements of photography:

reproducing an image, capturing time and fixing colour. Like utopias conquered

anew each time, photography reminds us of its importance in the discovery

of the world as we know it. It enables us to see, and asserts its political

and societal subjectivity. We take it for granted, sometimes forgetting that

capturing the image of the world is also a technical challenge, and above all,

an infinite source of inspiration for artists.