''We are not permitted to choose the frame of our destiny. But what we put into it is ours.'' – Dag Hammarskjold (1905-1961)

''Many a doctrine is like a window pane, we see truth through it, but it divides us from the truth.'' – Khalil Gibran (1883-1931)

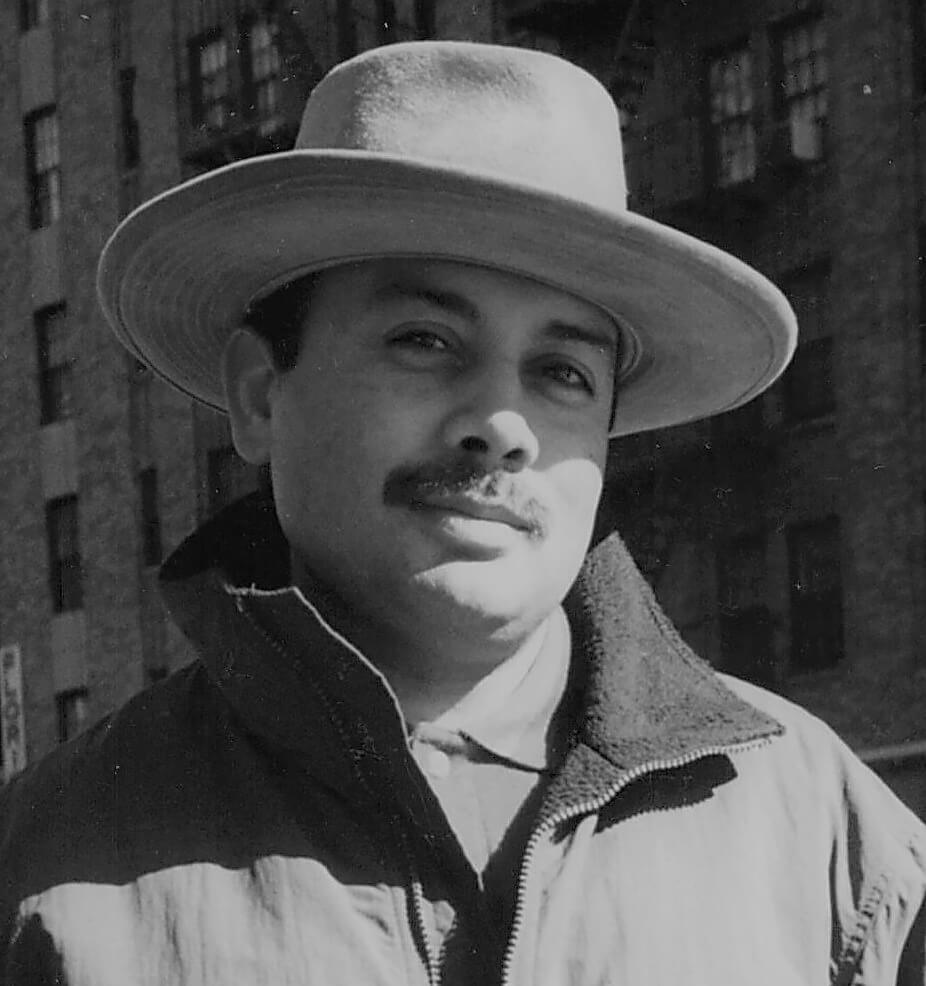

In the

National Portrait Gallery,

The Art Institute of Chicago, The

Louvre, and my library, there hangs one of the most iconic postwar

Chicago street-life photographs by Arthur Shay, titled: “Sunday Morning on Madison.” It was taken from a car window, in 1949, while in

the company of his friend, the National Book Award winner, Nelson Algren, the then soon to be lover of Simone De Beauvoir. The one in my

library, a rarer print, was signed and gifted by the maestro, the LUCIE Award winner, as quid-pro-quo for my review on his Gallery Loeb

exhibit in Paris, attended to by two prime ministers, a president, and others of consequence. Gallery Loeb was where a young Picasso was

introduced in a score old 20th century.

Shay's masterpiece of opportunity, framed by the car window, whose power of evocation of a vanished era is only offset by the provocation

of our melancholy. What makes this photograph aesthetically extraordinary is that it came with a “preexisting frame” of the car window, as

Shay put it, that had reduced precious seconds in composition, enabling him for a quick release of the shutter. The words frame and

composition have a symbiotic relationship in the arts, in life as well. We cannot compose anything without a setting, a perimeter, or a

boundary -- a frame. Ironically, it's the frame that gives structure, that gives us freedom to create a composition. The 1781 D Minor by W. A.

Mozart, or the 1937 Guernica by Pablo Picasso were created within a framework. In 1348-49, during the black plague, Giovanni Boccaccio

had sequestered himself within a room, as if within a frame, and wrote his hundred seminal and salacious tales set within a discrete

framework of female narrators. He was the father of the genre, followed by Chekov, Maupassant, Poe, and many contemporary others.

In 2009, I wrote a small fictional story based on the Shay photograph, developing the characters, their lives and that serendipitous

confluence, titled: “The Deconstruction of that Sunday Morning on Madison.” It was so convincing to the audience that Shay had to write a

letter to deny the verisimilitude of authenticity of the story to the magazine editor, to clarify that it was but a “brilliant” work of fiction.

Here's the link for the story, the letter and the photograph: http://www.swans.com/library/art15/rajup08.html We both had discussed that

photograph, and contemplated the effect of preexisting frames easing compositions.

What is a frame? I want to effect this subliminal priming within our psyche, so we become aware of frames everywhere. Well, everything

exists within a framework. Our frame of references, compositions, entertainment, work, family, society and its laws are efficacious only

within a framework – and all of such conditions yield aesthetic. The best example being the U.S. Constitution, which is the nation's frame. A frame constitutes restriction, boundary, discipline, control and most importantly, freedom. How about this morpheme? The word FRAME is

almost saying Fra-me: Frame-me.

Grammatically, the word frame has a binary morphology. It's a Noun, when it's an enclosure, especially, when it encloses societal dynamics,

arrests chaos by imposing structural control, in and for almost everything. As a Verb, it is the endeavor to put something within a frame, or

framing an innocent person with a crime he or she did not commit. At at metaphysical level a frame is “mental economy” that eliminates all

extraneous elements and the rampant absurdity in our lives. Well, this article is an exploration of the concept of Frame and framed

compositions that exist out there, whether through a window or any form of containment -- and, the variations of this theme in other forms of

art: visual and performance arts, Films, commerce and literature, last but not least, photography.

What is an Aspect Ratio? Ratio is the quantitative relationship between two numbers and the value contained within the other, like there 2

twos or 3 of the 4 singles within a 4. When I photograph, I prefer the aspect ratio 4:3, which is close to 35MM motion picture film. However,

I love watching motion pictures in 21:9 and 16:9, better known as widescreen. The portrait or vertical format does not make sense to me. I

even send my article submissions in landscape format. In visual arts, we use a frame to house our composition, and in motion picture arts, we

use it to contain action, I call it, dynamic composition, because, the subject matter moves in and out or within the frame – and this

choreography of angles and movement is cinematography.

This reminds me of the thrilling1954 psychological and voyeuristic Hitchcock masterpiece, “Rear Window” – in which a convalescing

photographer, played by Jimmy Stewart, believes and tries to convince his girlfriend, played by Grace Kelly, that he had seen a murder in a

neighboring apartment. The film's cinematography was choreographed entirely through window frames, as the protagonist watches the

neighbors' activities through their apartment windows, day and night, in which we see characters ingress and egress out of the scenes framed

by the static windows. The film is a rare thing of beauty, and is on AFI list of the 100 best films of all time.

Martin Scorsese had said

''Cinema is a matter of what's in the frame and what's out.'' The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York had

issued a book titled,

“Italian Renaissance Frames.” Then, there's another article by Lauren Collins in the New Yorker , titled,

''Looking at

Frames at the Louvre.''This article fixes on how the Curator of the department of paintings at the Louvre, Ms. Charlotte Chastel-Rousseau,

had organized an exhibit called: Looking at Frames.

''The idea was to interrogate the complex role of the frame...the frame must valorize the

work...''she had said. I agree with her notion, and would like to add that the frame, besides being an enormous factor in the act of

composition, also protects and isolates the content within it, eliminating the “noise,” enabling us to focus and derive pleasure when we see it.

Why do you think acoustically enhanced auditoriums are built for millions of dollars for operatic or orchestral performances? The art of the

sound and performance need to be put within a frame, to isolate it from interruptions of extraneous noise, so the viewer-listener is privileged

to enjoy the purity of the sound and performance.

The same goes for literary arts.

A structural framework is essential to effect maximum synchronous with the reader. Whether it's a novel, a

short novella, or a screenplay, it's within a structure, a framework of three acts: the beginning, a middle and the end. We must compose

within that framework to attain aesthetic and entertainment resonance. A photograph is a different proposition altogether. It's not a three act construct, but one quick instinctive composition of the whole. In photography, when it, the incidental composition comes together, either you

become aware instantaneously and are ready for it, or are too slow in reacting to or realizing it – which is the difference between us in the

billions and Cartier-Bresson, Shay and Kertesz.

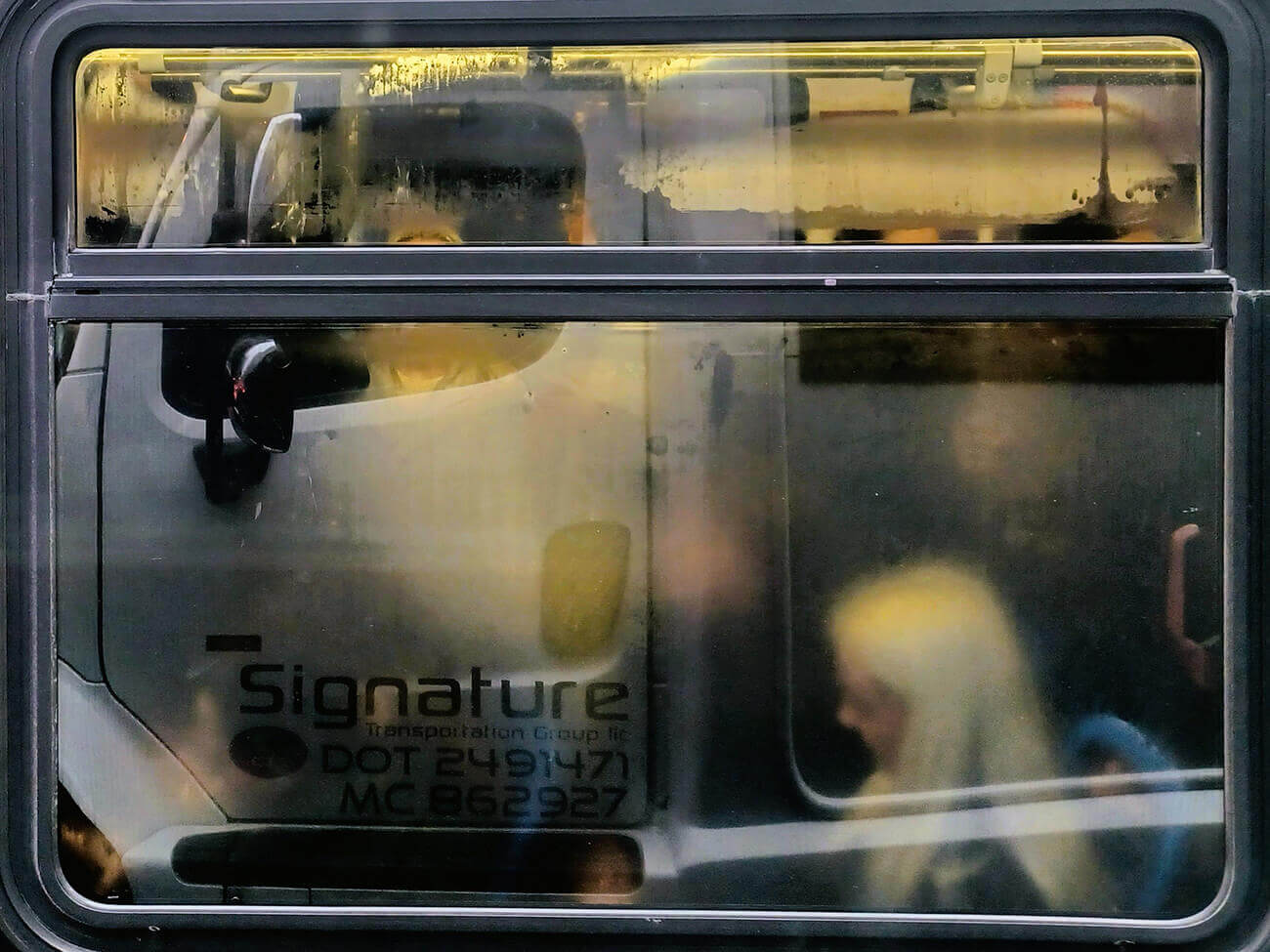

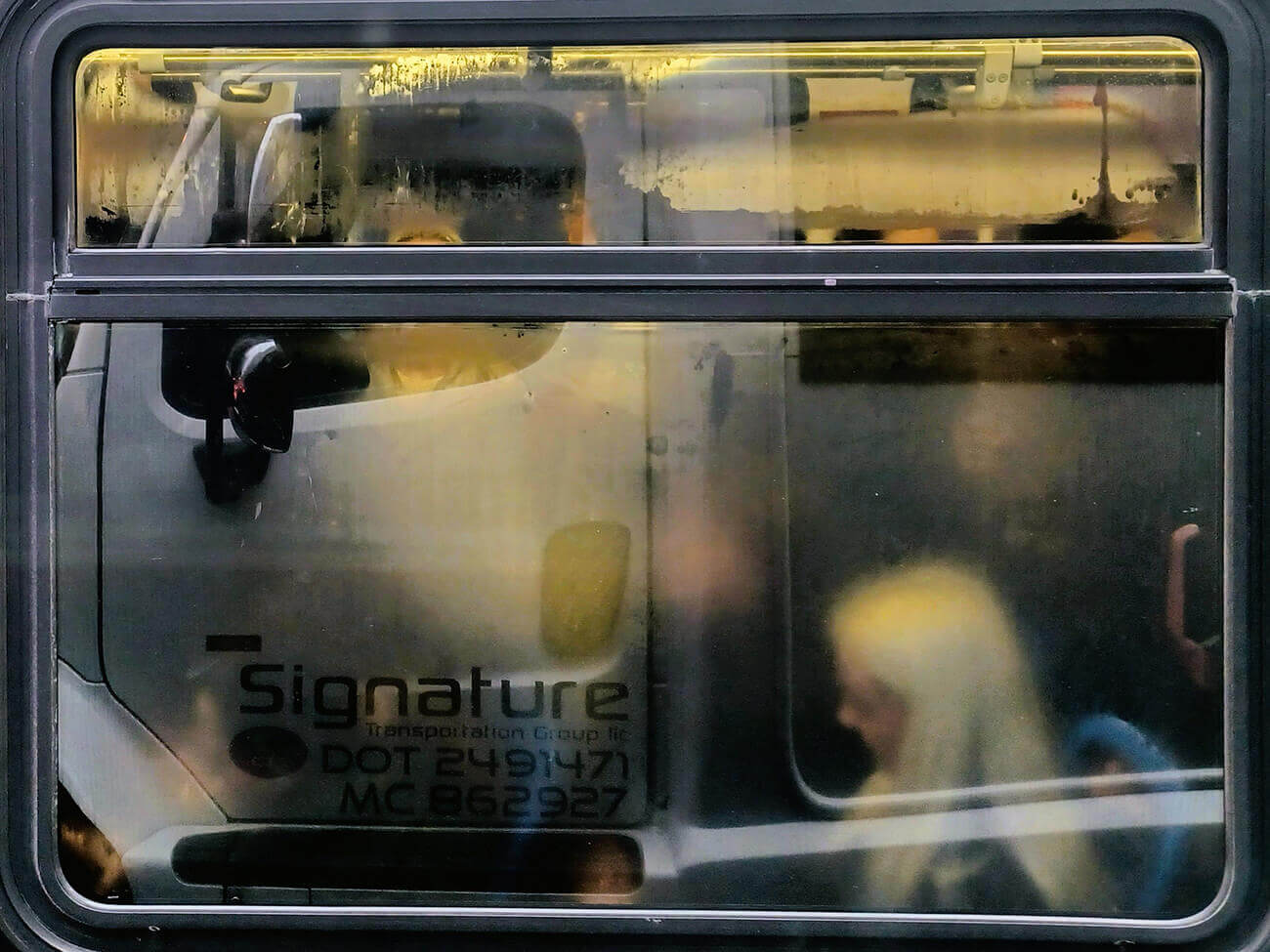

In my exploration, unlike Shay, who had shot from a stopped car window, I, on the other hand, attempted shooting with my smart phone

through two sets of moving window frames, mine and my subject's, both in the opposite direction, occasionally in the same, with surprising

effects. Shots were through several panes of glass on vehicles that were scratched, scuffed, distant, tinted and in movement. However, What I

discovered was that despite the lack of fundamental clarity, the aesthetic yield was enormous. The photographs appear foggy, frayed, faint

and illusory, more like a painting, yet, we could discern the condition within those frames.

In my compositions, difficultly wrought, I had experienced a phenomena. Within an extremely confined public space, everyone was hyper

private, composed, serious, with somber countenances, struggling to contain their inner contentions – the making of an intriguing study.

What was even more arresting were the looks. When the windows to our soul: our eyes, aligned and locked across the multiple panes of

glass, each of them yielded a different vibe. From “What's your problem?” to “What do you want?” to “Can I have some privacy?” to “leave

me alone” to “Peek-a-boo!” to “Get lost – up yours!” From direct contact to cross-eyed and everything in between, as you will see. Such are

the mundane wonders that we ignore or pass on everyday.

Here's another dichotomy, the

window frames reveal a strangely unique condition. Each individual is submerged in the collective. Every

type of collective condition is the by product of utter and absolute individuality. The individual creates, invents and realizes with industry,

thereby producing a specific collective condition. One can recognize these collectives rather easily: bankers and lawyers, construction and

maintenance, or the creative Ad agency types and others. People also look trapped within a box, being taken away involuntarily. They also

appear in stasis, an illusion, while the frame moves on laterally. Ironically, each of their condition is of their own making, voluntary, but the

collective is involuntary. It's an incongruous sight, seeing folks, in stasis, incarcerated and helpless, in a rectangle frame like that of a film,

being moved away laterally, instead of vertically, the feed on an old projector.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, the peerless impressionist, had captured the Parisian condition of summers in his mesmerizing works, and the

essence of that condition was not in the clarity, but in ambiguity. One didn't see it up close, one sensed it from a distance. In his paintings,

one could almost sense the fragrance, the rustling silks of fashion, the romantic frolic, the dappled shade of trees in the breeze, the banter in

laughter, and the clinking goblets. Walk into a room, you could immediately sense the warmth or the cold stares of folks. You see, clarity is

detail, our condition cannot be captured by clarity, it's distracting. Condition is the whole, it is only given to impressions – and sensing is

impressionism. It's been my attempt to use the most rudimentary, basic equipment to capture certain conditions as impressions, like the one

here, people in transit on city buses. Something so real, so mundane as folks on city buses could appear impressionistic, almost abstract, is an

astonishing visual treat. Which brings me to the point that there is, in fact, limitless facets of beauty. Inexorable reality: we do exist within

frames – our windows are relatively small, in time and space, therefore, shouldn't it be our (not just photographers) primary focus, to

experience as much as beauty as we can?

Copyrighted, February 18, 2024, by Raju Peddada. All worldwide Rights reserved on Text and

Photographs.