Yet another year where photojournalists have been prominent in tragedy.

First there was Afghanistan, then Ukraine, not to mention so many other theaters of

war, violence and atrocities standing as clear and often cruel evidence to prove that

photojournalism is a leader in advocating human rights, condemning war crimes, and

defending freedom of information, i.e. the right to critical information in a context of

democratic debate.

Photojournalists, through their physical bravery and their quest for truth, in their

investigations constantly pursuing facts and evidence, deserve our gratitude. They

are soldiers of peace and deserve our active support so that they can carry out their

professional duties under increasingly difficult and adverse circumstances.

Yet another year, and this time we shall be together in Perpignan, celebrating the

city known internationally as the capital of photojournalism extending a welcome

to photojournalists from across the world, with participation from French national

authorities, the region of Occitania, the département des Pyrénées-Orientales,

Perpignan Méditerranée Métropole, and the City of Perpignan, together with all the

partners from the private sector and the different teams working on the festival to make

Visa pour l'Image - Perpignan the major event that it is. All parties concerned are

pleased and proud to speak up, to speak out, for the 34 th time, stating their admiration

for photojournalism and reiterating their support for photography.

My personal ambition is for us to emerge from the crisis of the pandemic and have

the festival renew ties and acquaintances with everyone involved in photojournalism

around the world, with all the professionals who have chosen to work in photography

and are doing so with such spirit across the globe.

I wish to invite not only the professionals in the world of photography, but also

amateurs, and all advocates and supporters of freedom to come and explore the

many exhibitions displayed in the city of Perpignan, and to come and marvel at the

stunning evening programs on the giant screen in Campo Santo.

Yes, come and applaud the work of photojournalists whose range of interests and

commitments also go beyond the horrors of the world to perceive the delicacy and

beauty of nature, the environment and the human soul.

Renaud Donnedieu de Vabres: President of the Association Visa pour l'Image - Perpignan

Vyacheslav Veremiy - Andrea Rocchelli - Andrei Mironov - Igor Kornelyuk - Anton

Voloshin - Anatoly Klyan - Andrei Stenin - Serhiy Nikolayev - Pavel Sheremet - Vadym

Komarov - Yevhenii Sakun - Roman Nezhyborets - Brent Renaud - Maks Levin -

Oleksandra Kuvshynova - Pierre Zakrzewski - Oksana Baulina - Mantas Kverdaravicius

- Vira Hyrych - Oleksandr Makhov.

Since 2014, the Committee to Protect Journalists has recorded the deaths of twenty

journalists in Ukraine, twenty at the time of writing this editorial. Eight years have gone

by since Crimea was annexed and fighting broke out in the separatist regions of the

Donbas - eight years of war being waged in eastern Europe.

But Ukraine is not the only country where journalists are losing their lives. Since the

beginning of the year, far from headline news stories, some ten reporters have been

killed in cold blood in Mexico. And no one could forget the death of Shireen Abu Akleh,

shot in the head, reportedly by Israeli forces.

But this year Ukraine has been the main focus. So what should a festival of

photojournalism such as Visa pour l'Image do in response to such an event?

In September last year, pictures were screened at Campo Santo showing Afghans

fleeing the return of the Taliban, scrambling over planes on the tarmac at Kabul airport.

Who could have thought then that such images would be swept from world headlines?

No one perhaps, but certainly we had not imagined the prospect. This year we will

obviously be featuring Ukraine, giving the story the coverage it deserves, but we shall

not be restricting the program to one single event, no matter how important it is.

What's more, this latest war has highlighted, yet again, so many of the issues

confronting professional photographers, while also uncovering new developments in

photography. Key reports have presented the news in the midst of the confusion of war,

with substantial input from members of the visual investigation team of The New York

Times, working together with their reporters in the field and presenting incontrovertible

evidence to contradict the ''fake news'' spread by Russia on the Bucha massacre. And

they have provided evidence of atrocities being committed on both sides, confirming

the authenticity of a video showing Ukrainian soldiers executing a Russian soldier.

Such developments should not be seen as yet one more nail in the coffin of ''conventional''

photojournalism, but rather as an additional tool in the news ecosystem providing even

stronger backing for stories reported in still pictures and which, here at Visa pour l'Image,

is what we have been acclaiming and encouraging for so many years.

Looking inside the ecosystem, credit must be given to the exemplary and essential

work done by the news agencies (AFP, AP, Reuters, Getty and more). Their networks

of reporters, fixers and sources, their logistics and know-how make it possible for

media around the world to present day-to-day coverage of the war. In September, we

will have the privilege of presenting these pictures, exhibited on the walls in Perpignan

and on the giant screen at Campo Santo for all our visitors to see.

Jean-François Leroy: Director-General, Visa pour l'Image - Perpignan

Un migrant sous sa tente dans un camp de fortune en périphérie de Calais. 14 août 2020. © Sameer Al-Doumy/ AFP Lauréat du Visa d’or humanitaire du Comité international de la Croix-Rouge (CICR) 2022

Winner of the 2022 Humanitarian Visa d'or Award - International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC)

Fatal Crossings

The report, covering the period from August 2020

to May 2022, presents the migration crisis as

experienced in the north of France.

Many migrants have spent years crossing country

after country, fleeing war or natural disaster, then

reach the city of Calais on the French side of

the strait that is the narrowest part of the English

Channel. There they spend weeks in makeshift

camps hoping and waiting to reach the United

Kingdom, their ultimate destination.

People traffickers charge 3,000 euros for each

passenger boarding an inflatable dinghy with a

small outboard motor to cross the Channel and

land illegally in England in their quest for a new life.

On November 24, 2021, an inflatable dinghy with

27 migrants on board sank off the coast of Calais.

But such tragedies have no effect on migration

policies, yet, according to observers, such

policies aimed at border security are the cause of

these dramas.

Between January 2021 and November 24 when

the tragedy occurred, a total of 31,500 migrants

crossed the Channel from France to the United

Kingdom. For, since Brexit, with more stringent

security checks at the port of Calais and the

entrance to the Eurotunnel where migrants hide

on board vehicles, more and more have been

attempting to cross aboard flimsy dinghies. The

crossing is fraught with danger and now, after

the Mediterranean, the fear is that the English

Channel could become a new maritime cemetery.

Sameer Al-Doumy

Ana María Arévalo Gosen

Winner of the 2021 Camille Lepage Award

Días Eternos: Venezuela, El Salvador, Guatemala (2017-2022)

We must not forget that when a woman

is in prison, it is not one individual but an

entire social network that is suffering. In

the 21st century, the witch hunt continues:

women excluded remain trapped.

Lisset Coba, 2015

The dire situation of women in Latin American

prisons is rarely visible but has repercussions

throughout the region. The prison system is in a

critical state almost everywhere in Latin America,

and a woman behind bars can have a negative

impact on an entire generation.

This photographic work has focused on the

situation of women in prisons in Venezuela, El

Salvador and Guatemala, causing situations of

great vulnerability and lifetime stigma.

The set-up of most custodial centers cannot

provide separate facilities for men and women.

In Venezuela, for example, there is no remand

center for women only. Prisons for women, such

as Ilopango in El Salvador, have the same design

and construction as men's prisons. Prisoners

are not housed according to the offenses

committed or by age group, and they can be

held for long periods before their cases come to

court. For transgender women, the experience is

particularly cruel as they are denied their chosen

sexual identity and are held in custody with male

prisoners.

For female prisoners there is no assistance

offered to help them return to normal life and

mainstream society; they are locked away in

an atmosphere of distress and suffering, in

overcrowded cells, deprived of everything, held

for interminable remand periods, in violation of

their fundamental human rights.

© Ana María Arévalo Gosen

Winner of the 2021 Camille Lepage Award

What's more, women have fewer visitors than male

prisoners, yet they desperately need such visits

to survive the experience as contact with friends

and family is an essential way of maintaining

moral and mental health; it also provides for their

material needs as the national authorities fail to

supply proper food, medication and clothing.

No doubt the most difficult challenge in prison for

so many is for the mothers of young children. Of

the three countries featured in this report, there is

only one prison facility for women with children.

The mothers are obviously pleased to have their

babies and infants with them, but feel guilty for

inflicting such living conditions on them. And once

the child reaches a certain age (3 in Venezuela,

4 in Guatemala and 6 in El Salvador) they can no

longer stay with their mothers.

Yet despite all this, the women do have their own

life, forming strong friendships and displaying

great solidarity and resilience. Living together,

they share everything: food, bedding, clothing

and their own private stories. Their bodies

become symbols of resistance as they rebel

against a system which has deprived them of

so much. They tattoo their bodies, and do their

make-up and hairdos, because there are some

things that cannot be taken away.

Once the women leave prison, traumatized and

rejected, theirs is a life without hope, without

employment and with no support network outside

prison. When released, they are therefore likely

to return to the gangs they were involved with

before, and return to a life of crime.

Ana María Arévalo Gosen

Maéva Bardy

The Tara Ocean Foundation with the participation of Le Figaro Magazine

The Twelfth Expedition of the Schooner Tara

The month of October 2022 marks the end of

the twelfth Tara Ocean Foundation expedition.

In late 2020, the Microbiome Mission set off with

the vast ambition of studying invisible life in the

ocean, investigating microscopic organisms little

known even to scientists, and yet they are the

foundations of the greater marine ecosystem.

Over a total of 22 months, international specialists

in biology and biogeochemistry together with

skilled sailors have spent periods of time on

board the schooner Tara, following paths once

sailed by famous ships such as the HMS Beagle

with Charles Darwin on board and Ernest

Shackleton's Endurance, and going as far as is

possible across the planet.

The Microbiome Mission is a saga with many

chapters, and the exhibition has focused on one

episode in Tara Ocean history: the expedition on

the Weddell Sea, east of the Antarctic Peninsula.

In the face of roaring winds, the crew sailed

around giant icebergs, studying the melting of the

ice cap and the impact on the ocean which is one

of the world's largest carbon sinks. Almost 30%

of human CO2 emissions are captured by the

oceans, and 40% of that is in the Southern Ocean.

As ice melts at an ever faster and dangerous rate,

as temperatures increase in Antarctica, reaching

a record high in March 2022, it is essential to

gain an understanding of such effects requiring

humans to change and adapt.

Oceanographic expeditions are usually

conducted on board huge icebreakers or other

large vessels, but the Tara Ocean Foundation

initiated its small-scale model in 2003 and has

continued to use it, thus providing convincing

evidence that scientific studies can be carried out

on board less costly sailing boats, offering greater

flexibility for logistics and technical facilities and

causing less damage to the environment. The

Tara Ocean program, conducted in partnership

with UNESCO, the European Union and leading

international research institutes, has brought

change to the way basic research is conducted,

and continues to sail the world as did the great

explorers of the past.

Vincent Jolly, Feature Reporter, Le Figaro Magazine

Lucas Barioulet/Le Monde

Winner of the 2022 Ville de Perpignan Rémi Ochlik Visa d'or Award

Ukraine: war as a daily experience

5.30am, Moscow, February 24, 2022. Vladimir

Putin was seated at his desk and announced the

start of a special military operation in Ukraine.

The first strikes hit the country, and President

Volodymyr Zelensky called on his people to

take up arms. The life of millions of Ukrainians

changed in a matter of moments.

In a hospital in Kyiv, a mother is at her son's bedside;

she has been there for three months; he was

wounded in shellfire and his leg was amputated.

In what remains of Borodyanka, an elderly woman

is asking for directions; she is lost in her own

home town. In Lviv, the curator of a museum is

contemplating the empty walls. And a mother weeps

for her son, her second to die in combat.

Here it is not just land that is lost; it is an entire

country, its identity, heritage, and economy.

Some, people have had no other choice than to

flee; others have chosen to remain. Life is now

in underground shelters, in trains and tunnels, to

the sound of sirens as death comes from the sky,

and the trauma of war permeates every thought. ''I

saw a video showing Russian soldiers engulfed in

flames, and I laughed. For a moment there I didn't

know who I was; everything had changed. I would

never have thought I could behave like that.''

Alina, who lives in Kyiv, was telling her story.

The pictures here were done on assignment

between March and May for the daily newspaper

Le Monde. They are my endeavor to show the

everyday experience of war, to show the impact

it has on the people, presenting a documentary

record of their life which, while torn apart, still

continues. We realize that war is more than just

weapons and destruction, that it has an impact on

the lives of millions, some of them trapped in their

homes, their cities, their country. At a time when

news reporting has been exploited, distorted and

instrumentalized, it is essential to show the real

experience of war.

In the field are people doing their jobs: the fixers,

doctors, volunteers and soldiers, and when

we leave they remain, still working there. The

experience is on both the outside and the inside,

revealing what human beings can do, for better

or for worse, what can be seen and experienced,

and what the limits are. There is waiting, even

boredom, there is fear, doubt, a sense of

absurdity; there is life and death. These pictures

can only convey a split second of everyday

life out there where war is present, all the time,

relentlessly so.

Lucas Barioulet

Femmes, hommes et enfants vivent tous ensemble. Centre d’accueil psychiatrique d’Avrankou, Bénin, 2021. © Valerio Bispuri

My work tells the tale of mental illness today.

This is the fourth chapter on freedom lost (after

Encerrados, Paco and Prigionieri), continuing my

extensive, in-depth study exploring the world of

people hidden far from the public gaze.

Venturing into the realm of mental distress is a

complex, delicate and demanding experience,

and the challenge of presenting it through

photography is even more complex, delicate

and demanding. Who are these ''mad'' men and

women? What do they feel? In a bid to find

answers to these questions, I had to become

part of their universe. Their movements and

expressions are lost in an inner world, often totally

cut off from the surrounding environment which

they may see as hostile or even terrifying, a world

that can lead to self-destruction.

The starting point I chose was Africa, there where

mental illness has only recently been given formal

recognition. This makes it difficult to work out

how many people are mentally ill, and to find

where they live. Often they wander the streets

of huge cities, or they can be hidden away in

remote villages. Mental disorders are often seen

as an evil caused by non-human, supernatural

and sometimes threatening elements. This is

the case in north-western Africa, in countries

such as Benin, Togo and Côte d'Ivoire where

voodoo witchdoctors consider the mentally ill to

be demons and tie them to trees in the villages.

Fortunately there are some wonderful people

such as Grégoire Ahongbonon, a missionary who

for the past twenty years has been working to

have the mentally ill treated with dignity in special

centers which he has set up.

The first countries I visited were Zambia and

Kenya, in 2018, going to mental hospitals where

I saw the harsh reality of mental disorders, drug

addiction and patients simply abandoned in the

streets, both adults and children. In Kenya, I went

to the slums of Kibera and Mathare in Nairobi. In

Zambia, I went to the one and only mental hospital

in Lusaka, the capital city. I saw patients locked

in tiny cells, spending hours without moving,

foaming at the mouth, or others left to their own

devices, walking up and down the streets and

trying to shelter in the markets. Some were

born with mental disorders, while others have

destroyed their minds with drugs. Some have

suffered emotional trauma and lost all sense of

space and time.

During the pandemic, I kept on working, but

in Italy, at emergency departments admitting

patients to prison-security psychiatric facilities.

I would spend days with the patients, going

through all the stages, from acute crisis to

afternoons lounging around playing cards. The

time spent without taking photos meant I got to

know them, to look at them, to try and understand

them.

Most recently, in 2021, I went to Benin and Togo to

continue the work on Africa that is being exhibited

here.

I have always believed that both patience and

courage are needed for photojournalists to do

their job of telling stories that convey the real

experience. I always wait before I take a photo.

I try to fit in with the time of the person opposite

me. Who is the person? What do they feel?

Are they in a state of mental distress?

Valerio Bispuri

Mstyslav Chernov & Evgeniy Maloletka/ Associated Press

Mariupol, Ukraine

The dead were largely abandoned in the

streets. There were no funerals. No memorials.

No public gatherings to mourn those killed by

Russia's relentless attacks on the port city that

had become a symbol of Ukraine's ferocious

resistance. It was too dangerous.

Instead, authorities collected the bodies in a truck

as best they could and buried them in narrow

trenches dug into the frozen earth of Mariupol.

The mass grave trenches told the story of a city

under siege. There was the 18-month-old hit by

shrapnel; the 16-year-old killed by an explosion

while playing football; the girl no older than six

who was rushed to a hospital in blood-soaked

pajamas patterned with unicorns. There was the

woman wrapped in a bedsheet, her legs neatly

bound at the ankles with a scrap of white fabric.

Workers tossed all of them into the trenches,

moving quickly to get back to shelter before the

next round of shelling.

The world would have seen none of this, would

have seen next to nothing at all from Mariupol

as the siege set in, if it had not been for Mstyslav

Chernov and Evgeniy Maloletka, the Associated

Press team who raced to the city when the

invasion began and stayed long after it had

become one of the most dangerous places

on earth.

For more than two weeks, they were the only

international media in the city, and the only

journalists able to transmit video and still photos

to the outside world. They were there when the

young girl in the unicorn pajamas was rushed to

the hospital. They were there after the maternity

hospital was attacked, and for countless airstrikes

that pulverized the city. They were there when

gunmen began stalking the city in search of those

who could prove Russia's narrative to be false.

Moscow hated their work. The Russian embassy

in London tweeted images of AP photos with

the word ''FAKE'' superimposed in red. At a U.N.

Security Council meeting, a top Russian diplomat

held up photos of the maternity hospital insisting

they were fake.

Eventually, the team were urged to leave. A

policeman explained why. ''If they catch you, they

will get you on camera and they will make you say

that everything you filmed is a lie. All your efforts

and everything you have done in Mariupol will be

in vain.''

It was terrible to leave. They knew that once they

were gone, there would be almost no independent

reporting from inside the city. But they felt they

had no choice. So they left, slipping away on

a day when thousands of civilians were fleeing

the city, passing Russian roadblocks, one after

another.

Their work and the people they met speak for the

agony of Mariupol. Like the doctor who tried to

save the life of the little girl in her pajamas. As he

pumped oxygen into her, he looked straight into

the AP camera. He stormed with expletive-laced

fury: ''Show this to Putin: the eyes of this child and

the doctors crying!''

Sabiha Çimen

Winner of the 2020 Canon Female Photojournalist Grant

Hafiz

Muslims who memorize the entire Quran earn the

title of ''Hafız'' to be placed before their name. The

belief is that whoever memorizes the holy book

and follows its teachings will be rewarded by

Allah and will be raised to high status in paradise.

The practice dates back to days when illiteracy

was widespread, and paper and vellum were

prohibitively expensive. The Quran has a total

of 604 pages and 6,236 verses, so the hafızes,

as the guardians of the holy word, have helped

keep the text alive. The tradition of committing

the verses to memory, dating from the time of

Mohammed, has been practiced and passed on

through the generations for almost 1,500 years.

In Turkey, thousands of Quran schools exist for

this purpose, and many are for girls. The students,

aged from eight to nineteen, usually take three

or four years to complete the task which requires

discipline, focus and devotion. After the girls

graduate, most of them marry and have families,

but they will always remember the words of the

holy book.

My aim is to show the everyday life of female

pupils in Quran schools preparing to become

hafızes, including moments outside their studies

when having fun or even breaking the rules. The

narrative showing the girls' individual experiences

stands as a record. Through these photographs

I want to give the girls the possibility of speaking

for themselves, thus avoiding any misconceptions

or misinterpretations. Outsiders will see a rare

view of the female perspective, with nuanced

perceptions. My goal is to cast light on the

experience, offering insights into the hearts and

minds of young girls just like me and my twin

sister as we were 18 years ago.

My sister and I attended a Quran school from the

age of twelve. I can therefore reveal this unknown,

unseen world. My project shows not only the

journey of the students on their way to becoming

hafızes, but also shows that they can, as young

hafizes, entertain dreams and have the same spirit

of adventure as other young women of their age.

Hafiz is my first long-term project and began in

2017. Thanks to the support of the Canon Female

Photojournalist Grant (2020), I have been able to

develop the project with additional content

and images.

Sabiha Çimen

Jean-Claude Coutausse

On the Campaign Trail

Does political photography serve a purpose?

Not really, or perhaps not at all. It depends on the

sincerity of the photographer. A picture can never

tell the truth, but it should not mislead.

I no longer present politics as a comedy;

I stopped doing that when I realized that the

characters in front of me were from a tragedy.

I am not talking about distinguished members

of parliament or ministers, but rather about the

few men and women who put their lives and

reputations at stake in a bid to conquer the

ultimate position of power which they willingly

accept. These are the ones who never give up.

While working for the daily newspaper Le Monde

I have been able to cover political leaders,

following them at close range to capture moments

of joy, exhaustion and doubt that all contribute

to their portrayal. The editorial team of Le

Monde newspaper where the written word reigns

supreme has, for fifteen years now, accepted my

fragile images.

The only way I can cover politics is for a

newspaper. There is no such thing as universal

photography; we need to know who the audience

is. I know who the readers of Le Monde are, just

as I knew the readers of Libération in the 1980s.

Working for an editorial board is also a way

of getting away from the pressure of the

communications staff, those people who

have turned political reporting into captive

photojournalism, cutting back on space to move

and time to shoot pictures, bringing us in line

with official views and replacing us with in-house

photographers. Therefore I am also covering politics

to stop communication taking over the real world.

Jean-Claude Coutausse

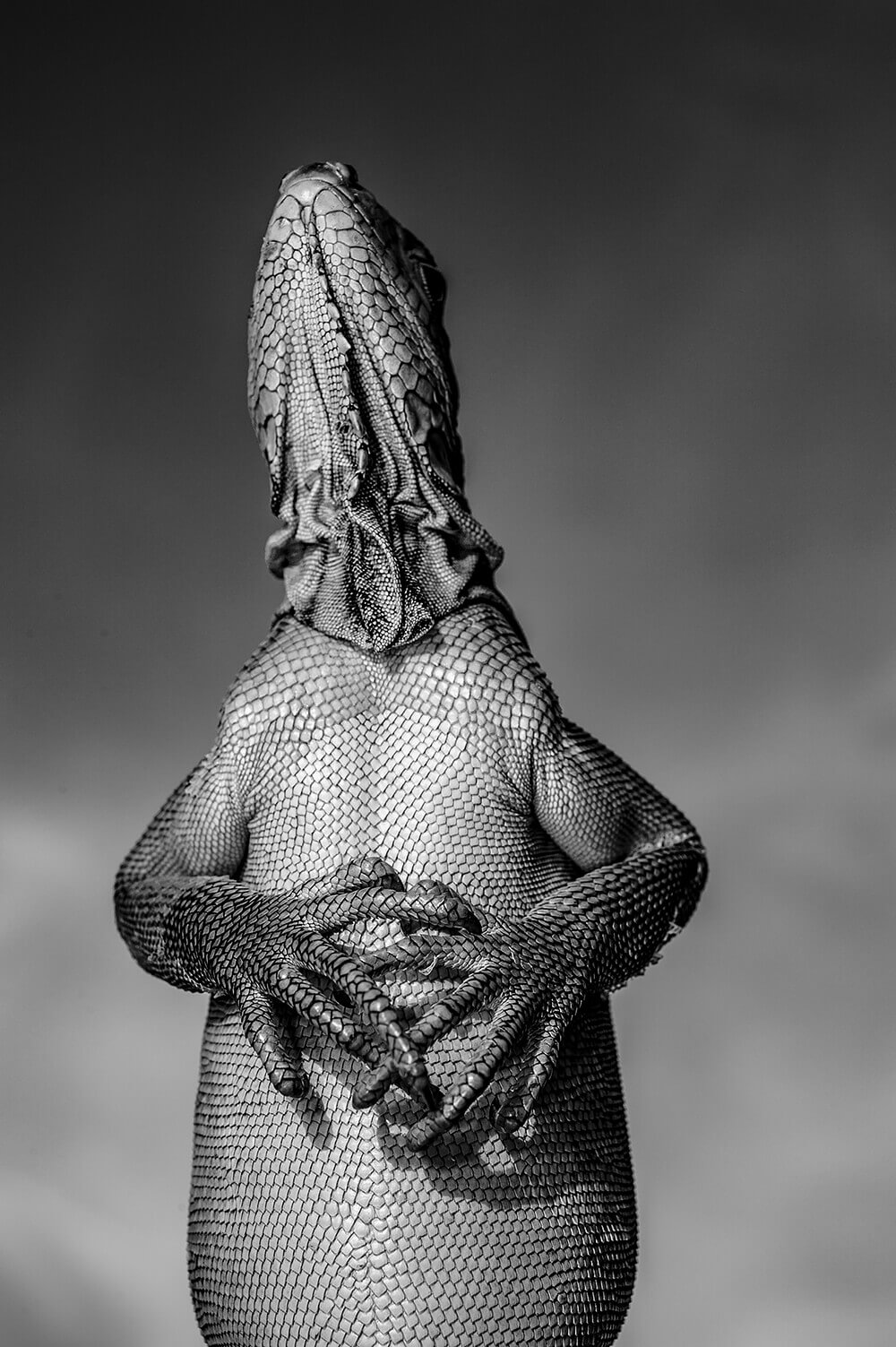

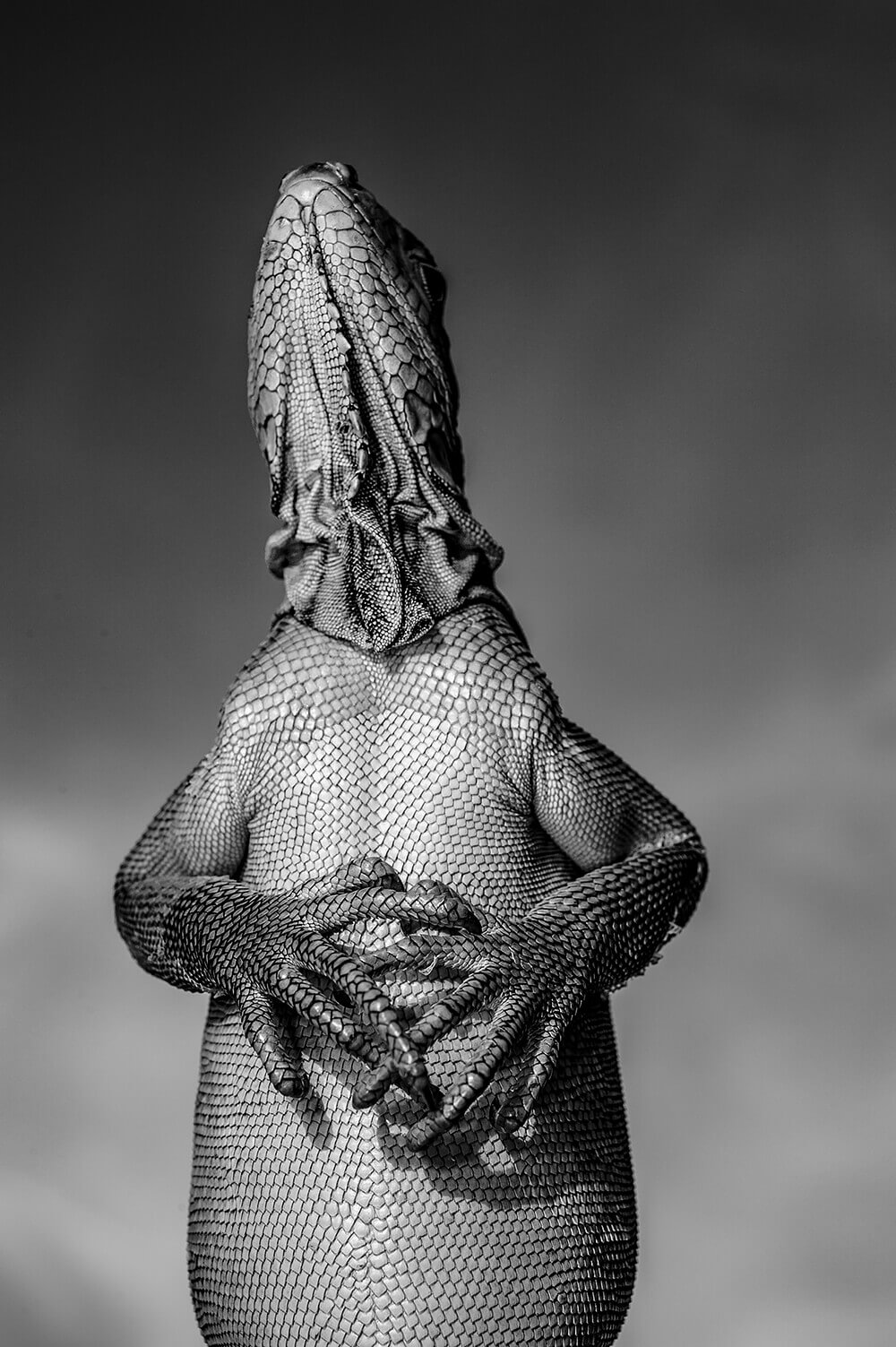

Iguane des Petites Antilles (Iguana delicatissima), île de la Grenade, Caraïbes. Espèce vulnérable (UICN). © Alain Ernoult

The environmental apocalypse confronting the

world today now has recognized causes: climate

change, overexploitation of resources, pollution,

the loss of natural habitats, invasive species and

the impact of massive deforestation and intensive

agriculture, all causing permanent damage.

Since 1970, vertebrate populations have declined

in size by 60%; since 1980, some 600 million

birds have been lost across Europe.

The future of the planet also depends on

the oceans responding to climate change.

Plankton and phytoplankton absorb CO2, but

as temperatures rise and the oceans continue

to absorb more carbon, the sea water becomes

more acidic. And there is pollution, including

industrial waste with heavy metals, solvents and

toxic sludge. As a result ''dead zones'' have

formed, unable to support most marine life;

worldwide there are now more than 400 marine

dead zones. The impact can be seen at every

level, from coral reefs to fish and crustaceans.

According to the report by IPBES, the United

Nations expert group on biodiversity, a large part

of nature has already been lost and the decline

continues. Of an estimated 8 million animals on

earth (including 5.5 million insects) up to one

million are endangered, and many could become

extinct in a matter of years.

Certain species seen as more ''charismatic''

by humans (the lion, elephant, giraffe, leopard,

cheetah, gorilla, panda, wolf and polar bear)

can be ecosystem engineers; the elephant,

for example, brings down trees and stops the

savannah from turning into a forest. There

are also umbrella species providing indirect

protection to other animals in the same habitat.

As large mammals are less diverse they are more

vulnerable, and losses of these populations are

only the tip of the iceberg of massive decline in

biodiversity and the collapse of ecosystems.

My work on the ''6th Extinction'' is intended to raise

awareness on the vulnerability of species around

the world. The photographic concept is designed

to convey the emotional impact, being as close as

possible to the animal so as to capture the magic

then conveyed in the pictures. By seeing other

species, by being attentive and acutely aware

of non-human species and our relationship with

them, we have the values needed to observe our

own world.

Alain Ernoult

Françoise Huguier/Agence VU'

Discretion

For more than forty years the photographer

Françoise Huguier has been working discreetly.

She all but defies description, but when trying to

observe her at work, it becomes apparent that she

is only rarely seen taking a photo.

The woman is invisible, a distinguished reporter

distinguished by the art of disappearing, ready

to lurk in waiting, in ambush perhaps, whether

backstage during a fashion parade, in shadows

in Africa or Siberia, in old communal apartments

in Saint Petersburg, or behind the scenes in a

Korean company.

There is no rush to grab the camera. She listens

as people talk about their lives, asking a minor

question that can open the path to scenes inside

the everyday routine. And so her investigation

techniques have developed.

(Translated, abridged and adapted from a text by

Gérard Lefort)

Acacia Johnson

Winner of the 2021 Canon Female Photojournalist Grant

The Pilots Connecting Remote Alaska

Across Alaska's rugged, diverse, and sparsely

populated terrain, one sound can be heard almost

anywhere: the distant drone of an aircraft. Only

20% of Alaska is accessible by road, and dozens

of its remote settlements, predominantly Alaska

Native communities, rely on aircraft for essential

services including mail and groceries, medical

care, and emergency transport.

Since the first mail-delivery plane took off in 1924,

small aircraft capable of landing on short runways

or on natural features like tundra, glaciers,

beaches, and water have played a critical role in

Alaska's development. Today, nearly all of Alaska

is highly dependent on aviation, both for essential

transport between communities and to access

remote wilderness areas. For many pilots, flying

is simply a way of life, a way to connect with the

landscape and each other.

Throughout my life in Alaska, I have known

flying to have an almost spiritual aspect. It

commands attention to safety and a deep

respect for the land, weather, and the lives of the

people onboard. While flying in Alaska is now

commonplace, it is frequently romanticized as

a dangerous enterprise. The early era of bush

flying between the 1920s and 1950s is famous

for the first bold pilots who flew without weather

forecasts, navigational technology or runways,

and who subsequently took risks with the weather,

survived crashes, and were often stranded alone

in the wilderness. Although the safety of modern

aviation has progressed considerably since that

time, the idea that flying in Alaska is dangerous

still lingers, to the detriment of professional and

private pilots who devote their flying careers to

operating safely.

From the city of Anchorage, to the Arctic, to the

Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, these are portraits of

pilots who have been part of the Alaskan aviation

community for decades and of those who are

helping to shape its future. Their airplanes also

represent a living portrait of Alaska's past: most

aircraft chosen by these pilots (e.g. the Piper

Super Cub and de Havilland Beaver) have been

used, maintained, and passed on between

generations of pilots since they were first

produced in the mid-20th century.

As one pilot told me, ''So much happened

before the time of airplanes, and so much will

happen after the time of airplanes.'' As the

aviation industry undergoes rapid changes

with skyrocketing insurance costs, advances in

electric aircraft, and the recent approval of cargo

drones, the future of flying in Alaska is uncertain.

To Know the Earth from Above frames a pivotal

moment in time, telling the stories of pilots who

connect remote communities, rescue people

in need, teach and inspire newer pilots, and

transport people to the wildest parts of the state.

Acacia Johnson

Selene Magnolia

''Zor'' Inside Europe's largest Roma ghetto

In Europe today with the challenge of

unprecedented migratory flows and nationalist

movements operating not only along borders

but also inside countries, minorities have been

forced into ghettos where they are cut off, needing

to be healed and prevented from infecting the

immediate environment.

In 2019, Europe had more than 11 million

members of Roma and Sinti communities, a

number equivalent to the entire population of

Belgium. But Roma communities suffer systematic

discrimination. In June 2021 in the Czech

Republic, a Roma man died when police officers

knelt on his neck. In November 2021 in Greece, a

little Roma girl was crushed by a gate, and died

after more than an hour while passers-by simply

looked the other way.

According to the European Union Agency for

Fundamental Rights (FRA) in its second survey

on minorities and discrimination (EU-MIDIS II),

80% of Roma people are at risk of poverty. The

same survey reported that Roma people formed

the largest minority in Europe, and suffered more

discrimination than other groups.

In the city of Plovdiv in Bulgaria is Stolipinovo, the

largest Roma ghetto in Europe. In the Communist

era, it was an ordinary neighborhood, but became

a ghetto after the fall of Communism and with

the privatization of industry when Roma people

lost their jobs because of discrimination. Today,

the people of Stolipinovo (approximately 80,000

according to the European Forum for Democracy

and Solidarity) are social outcasts rejected by the

Bulgarians living in Plovdiv.

The residents in the ghetto of Stolipinovo have a

Turkish background, speak Turkish and identify

as Turks. Most are Muslim, but diverse religious

identities, including paganism, coexist within the

community. The social structure is based on the

family unit, with clearly defined gender roles and

hierarchies according to levels of respect from the

community and wealth. Cultural traditions are core

values; events are celebrated in the open, usually

on the streets, and are open to the community.

Residents of the Roma ghetto of Stolipinovo

are victims of discrimination, being seen as

stereotypes not fitting in with the local Bulgarian

lifestyle and culture. They live in squalid

conditions, with social, housing and health

problems at critically dangerous levels.

Stolipinovo, being surrounded by hostility and an

atmosphere of increasing nationalist sentiment,

stands as a portrait of systematic discrimination in

Europe in the 21st century.

Selene Magnolia

Siegfried Modola

Inside Myanmar's Armed Uprising

In Myanmar hopes for peaceful, democratic

progress have faded. The Southeast Asian nation

is now mired in conflict and chaos. Decades of

poor governance and repressive military rule

created a climate of violence, human rights abuses

and chronic poverty. Steps towards democratic

change were dashed when the military seized

power in a coup on February 1, 2021.

Thousands of civilians have been killed as fierce

resistance from newly formed militias and ethnic

armed groups are now waging guerrilla warfare

on multiple fronts across the country.

In the town of Demoso in Kayah State, destroyed

buildings and empty streets testify to the intensity

of the clashes. Most of the area is under the

control of the armed wing of the government in

exile and the Karenni Army that has been fighting

the armed forces of Myanmar, the Tatmadaw, for

over 70 years.

Maw Soe Myar* is no ordinary child. She is only

one year old but her world has been turned

upside down by the cruelty of a regime that

plunged her country into violence and uncertainty,

forcing thousands of families like hers to flee.

Gone are the familiar voices of neighbors echoing

through the village; gone are the bright colors of

the floormats in her home, and the whispers of

her parents rocking her to sleep at night. What

remains is the silent, somber look of her mother,

Maw Pray Myar*, as she carries her across rocky

valleys, through teak forests and tall, sharp,

elephant grass that scratches her skin. Every step

is a calculated move for fear she might trip and

hurt her baby girl. They cross the Salween River

and venture into a thick bamboo jungle, towards

the border with Thailand, to safety. Here hundreds

of displaced families have found refuge from the

regime's brutal crackdown.

In another IDP camp not far from Demoso, a

woman voices her worries while keeping an eye

on her three children playing beneath a clear

blue sky. ''We always live in fear of airstrikes by

the military. We know it is easy for them to attack

civilians. That is what they do.''

In an attack by the Tatmadaw in Hpruso Township

(Kayah State) on December 24, 2021, at least

35 people, including four children and two

humanitarian workers, were burned alive. On

January 17, 2022, it was reported that an airstrike

on an IDP camp had killed two young sisters in

their sleep and an older man nearby, and left

hundreds injured.

Despite all odds, over the past year a growing

sense of comradeship has spread throughout the

population, with what seems like millions in both

cities and rural areas rallying to the cause, putting

their normal lives on hold to help in one way

or another in the struggle for a future free from

military rule.

In a hospital at a secret location near Loikaw, the

capital of Kayah State, thirty medical students

who followed the Civil Disobedience Movement

are now de facto doctors, treating patients

with the limited medical supplies available. A

22-year-old medical student from Yangon who

joined the uprising described the situation. ''We

lack medicines to treat the injured. We have to

refer many to other hospitals, far away, through

government-controlled areas.'' Pausing by the

bed of an eight-year-old boy suffering from severe

burns to his legs she explains, ''We do our best

with what we have.''

Siegfried Modola

All photos taken in Kayah State. [*All names have been changed.]

Les filles portent des robes neuves pour la fête de Norouz, le nouvel an du calendrier persan. Le père et le fils réparent la moto. Kaboul, mars 2018. © Andrew Quilty / Agence VU’

It was a harsh winter starting in 2013 that Afghans

faced. In the city of Herat on Christmas Day,

people burned trash by the side of the highway

to keep warm after fleeing fighting and, ironically,

drought in outlying rural districts. But there was

hope, wary though it may have been. In 2014, for

the first time since the fall of the Taliban in 2001,

the presidential election, previously organized

by international players, was to be organized by

Afghans.

At dawn on election day, the sound of exploding

rockets echoed through Kabul. The Taliban had

promised bloodshed. The skies were gray, but

voters waited in line in the rain, patiently coping

with the inevitable logistical hitches and security

threats. A total of 6.5 million votes were cast and

the day was heralded as a success.

The excitement, however, was short-lived, and

pessimism soon shrouded the country. When the

run-off vote between the two leading candidates

resulted in accusations of fraud, an audit was

called. Confidence in the Afghan republic

plummeted, as did the national currency and

foreign investment, while unemployment soared.

At the end of the year, the international military

mission handed responsibility for security over to

Afghan national security forces.

The Taliban had been biding their time until the

better equipped, better trained and motivated

foreign forces departed, then quickly went on

the offensive. They overran their first major city in

September 2015 when they captured Kunduz in

the north. During the operation to recapture the

city, US airstrikes destroyed a trauma hospital run

by Doctors Without Borders, killing 42 patients

and staff in one of the most horrific incidents of

the entire war.

As the momentum of the Taliban on the battlefield

surged, American diplomats revived efforts for

peace talks with the Taliban. In February 2020,

after 18 months of negotiations under President

Trump, the deal to bring peace to Afghanistan

was signed by representatives of the US and the

Taliban, in effect signing America's defeat with

the provision for the Afghan government and the

Taliban to engage in peace talks of their own, and

for international forces to withdraw entirely the

following year. But the United States, under both

presidents Trump and Biden, was more intent on

withdrawal than on sustaining stability

in Afghanistan.

In early 2021, after President Biden confirmed that

the US would abide by the withdrawal agreement,

the Taliban stepped up offensives across the

country, overrunning rural districts at great speed

as government forces crumbled, many simply

laying down their weapons and surrendering.

By early August, Afghanistan's 34 provincial

capitals were all virtually surrounded. With the

prospect of a no-holds-barred battle for Kabul, the

remaining foreign forces and diplomats hastened

their evacuation efforts. In the end, the Taliban

regained power much faster than even they had

predicted. It took just ten days for all but a handful

of provincial capitals to be overrun by the Taliban.

By dawn on August 15, their fighters had reached

the gates of Kabul.

For two weeks, victorious Taliban fighters guarded

Kabul International Airport where foreign forces

under the command of the US Army were airlifting

as many as 10,000 people a day: foreign

diplomats, aid workers and journalists, but mainly

Afghans, desperate to flee. Scores were killed,

crushed in the crowd or shot by Taliban fighters

trying to control access to the airport as tens of

thousands attempted to make their way inside.

An ISIS suicide bomber attacked, killing 180,

including thirteen US troops. Days later, in an

apparent bid to prevent a follow-up attack, a

family home was struck by a Hellfire missile fired

by an American drone. The ten victims, including

eight children, were buried in a cemetery by the

airport as the last American planes climbed into

the sky leaving Afghanistan for good.

Andrew Quilt

Eugene Richards

An Outsider

Based on some fifty years of photography, this

exhibition could be structured chronologically,

from my very first photographic stories in the

American South in 1969 till I returned to the

Arkansas Delta in 2019. On the other hand,

it could be structured thematically: American

poverty, the plight of the mentally disabled, the

human cost of drugs, of war, a woman's cancer.

Either approach would make it seem that from the

outset I had a part in planning this exhibition. Not

true. I began searching out these photographs

long months ago at my son Sam's suggestion.

He witnessed my feeling especially down, frozen

in place. The deadly spread of Covid was on

my mind, as were Afghanistan and Iraq and the

realization that other wars were looming.

I was also struggling to come to terms with the

societal divisions and in turn journalistic changes

in America. There were increasing numbers of

promoters of identity politics suggesting that some

of us are more worthy of support doing stories

than others. That the age, race, class, gender of

journalists are factors to be considered before

sending us out into the world. Additionally it

appeared to me that, with the possible exception

of photos of war, the pictures being published in

books and news magazines were less and less

of the moment, more often set up, constructed,

in collaboration with the subjects. ''Collaborative''

being a kind of buzzword of our time.

As happened, it was my son who directed

me toward an alternate way of publishing and

speaking out. ''There's pretty much no support

right now for what you feel you should be

doing,'' Sam observed, ''so put your pictures on

Instagram.'' ''Instagram,'' I said incredulously.

Then as if on auto-pilot I began to flip through the

warped, cracked binders of contact sheets that

take up seven or eight shelves in a back room

of our house. Leafing through the pages, I went

looking for pictures I hadn't shown or published

before, sifting through hundreds of moments in

the lives of others, awash in memories.

Then, much to my surprise, Jean-Francois*

phoned. This is a man who doesn't care who

you are, what age you are, where you are from,

what your gender identification is, as long as you

are attempting to tell the truth. His interest in my

pictures, along with Sam's and my wife Janine's

tender treatment of me, got me back to work.

Eugene Richards

*Jean-François Leroy, Director-General, Visa pour l'Image

Arnaud Robert & Paolo Woods

Happy Pills

For a long time the question of happiness was

considered to be a matter for religion, philosophy

or even politics. But today the pharmaceutical

industry is using science, marketing and

communication to provide a standardized

response so that human aspirations can be

fulfilled. The idea of a magic pill conjures up

many familiar images, e.g. Alice in Wonderland

or The Matrix, and is seen as an almost

magical response to help cope with moments

of weakness, melancholy or other pressures on

human existence. The promise of a chemical

compound that is able to cure and transform

provides the perfect metaphor for a Promethean

society focusing on efficiency, power, youth and

performance, a society where the appearance of

happiness is almost as good as happiness itself,

where appearance prevails over genuine feeling.

For five years, journalist Arnaud Robert and

photographer Paolo Woods traveled the world

seeking out Happy Pills, drugs able to ease the

pain of human suffering, to achieve excitement,

work, power, and action, with formulae capable of

retrieving patients from the abyss of depression,

with painkillers ingested by the working poor

who are simply trying to feed their families.

Everywhere around the world, whether in Niger,

the United States, Switzerland, India, Israel or the

Amazon, the Big Pharma world has expanded

and is offering overnight solutions where once

there were eternal problems.

The exhibition features a series of photos

plus ventures into social media, for an original

presentation confronting us with our own

relationship to medical drugs.

Happy Pills is also a book published by Delpire

& Co. and a documentary film produced by

Intermezzo/ARTE/RTS.

Exhibition produced by the Ferme des Tilleuls, Switzerland.

Alexis Rosenfeld in partnership with UNESCO

1 Ocean

1 Ocean, A Decade of Exploration in the

21st Century is a project conducted by the

photographer Alexis Rosenfeld in partnership with

UNESCO. As part of the United Nations Decade

of Ocean Sciences for Sustainable Development

(2021-2030), we are telling the story of the Ocean,

of its riches, of threats affecting it, and solutions

we can provide. 1 Ocean is a journey of discovery

of the Ocean, over a full decade seeing secrets at

great depths and the wonders of marine life.

The feature report has been developed along

three key lines.

EXPLORING

For centuries, basic curiosity has been the central

driving force urging human beings to explore,

to slake their thirst for knowledge, climbing ever

higher, crossing deserts and diving to extreme

depths in the Ocean. Such human ventures in

the past had one sole purpose and that was to

provide knowledge to the human race, knowledge

of worlds hitherto unknown, never even imagined,

but they also revealed fragile aspects of the

environment. Explorers who traveled the world

related their experiences and, in many ways,

shaped the legend of the ''blue continent'' as seen

on the surface, but there was another world far

below, a world all but beyond the scope of human

knowledge, almost impossible to reach. Now, in

the early 21 st century, the ''1 Ocean'' crew has

embarked on voyages of discovery of unexplored

realms, uncovering many mysteries of the Ocean.

REPORTING

The reason for this exploration is to generate new

knowledge. Explorers of the past who traveled the

seas would return with objects that were added to

the great collections of Europe: stones, botanical

specimens, art works and artefacts were brought

back, thus providing future generations with

valuable samples from the past. Today, following

the example of our predecessors, 1 Ocean,

A Decade of Exploration in the 21 st Century

will produce new content. Alexis Rosenfeld is

providing visual coverage of the journeys, through

both still photography and documentary films.

SHARING

This documentary record is designed so that

everyone can see the story of the Ocean and its

riches. The idea of sharing knowledge, passing

it on from generation to generation is a key part

of the project which is founded on the principle

that knowledge is the first step on the path to

protection. Given the environmental threats to the

Ocean today, we are duty bound to report on this.

Our ambition is to raise awareness in minds today

and, above all, to build the minds of the future.

Alexis Rosenfeld

Tamara Saade

Tiers of Trauma

Some might think the catastrophe that happened

in Beirut on August 4, 2020, and the crisis that

hit Lebanon happened from one day to the next,

but there had been more than three decades of

negligence and corruption flowing through the veins

of the nation, bringing the country to its knees.

On August 4, 2020, ammonium nitrate stored in

unsafe conditions in the port of Beirut, caught

fire and exploded, killing more than 200, injuring

6,000, and leaving 300,000 homeless.

The disaster struck in the midst of the Covid-19

pandemic and at the beginning of what would

become one of the worst economic crises in the

world, just a few months into what the Lebanese

call ''the revolution.''

The previous year, on October 17, 2019, tens of

thousands of Lebanese had taken to the streets

in protest against deteriorating living conditions.

It was the first time in years that the country had

witnessed such a strong sense of unity, but the

dream was to be short-lived.

The exhibition documents the past two years in

Lebanon, focusing on protests across the country,

and the aftermath of the explosion, as well as

some rare lulls in between. Not a single soul in

Lebanon has been left untouched by the events

of the past two years. Financially, those who had

savings lost their money. Physically, there was

the explosion that left more than 300 disabled, the

everyday stress facing everyone in Lebanon, plus

the Covid-19 pandemic, and many have simply

been unable to cope. The country's morale too

has been hard hit as it appears to be in a state

of depression, suffering constant anxiety, and

even ''schizophrenia'' as citizens attempt to lead a

normal everyday life in such an absurd setting.

People have been trying to get things changed;

some have focused on the prospect of the

elections in May 2022, while others have

taken to the streets to express their anger. But

change takes time, and Lebanon seems to be

running out of time. A huge proportion of the

younger generation has now left the country, and

understandably so as they choose to leave in the

hope of finding a ''normal'' life somewhere else,

i.e. a life where buildings have not been gutted by

an explosion, where streets have electricity, and

children can dream of the future.

To date in Lebanon, there has been no change.

Since 2019, there have many changes of

government, but with no impact. In fact, things

seem to have gone from bad to worse.

Lebanon is no longer a country at war. It has

been and remains to this day a country in conflict,

surrounded by war, and at the mercy of foreign

players.

Until change comes, until justice is done, and until

the families of victims of government negligence

over the past few years are given the response

they need, these pictures will stand as evidence

of the injustice prevailing in the country.

Tamara Saade

Exhibition supported by the French Ministry of Culture and MICOL (France's interministerial coordination mission for Lebanon)

George Steinmetz

Global Fisheries Harvesting Marine Wildlife

The past two decades have seen a rapid

expansion of fishing on an industrial scale with

international fleets of mega-trawlers, super-

seiners, and factory motherships competing with

increasing numbers of native fishing boats to

strip the oceans of marine life. This is a classic

example of a tragedy of the commons where

individuals voraciously deplete a shared resource.

The severity of the global problem was recently

quantified in a ground-breaking ten-year study by

Daniel Pauly (University of British Columbia) which

showed that the number of fish being caught

worldwide is 50% higher than figures reported

by the UN Food & Agriculture Organization, the

reason being that the source data is self-reported

by each country. Pauly's team painstakingly

reconstructed historic data to show that the global

fish catch peaked in 1997 at 130 million tons;

since then it has declined by 1.2 million tons a

year even though there has been a huge increase

in the number and size of fishing boats, and new

fish-finding technologies. There are clear signs

that wild fish stocks are plummeting as humans

accelerate the harvesting of the biosphere.

The photographs in the exhibit were taken

over the past six years in nine countries.

They document some of the largest and most

sophisticated new ships harvesting marine

wildlife, as well as poor fisherfolk from some

of the world's least developed nations who are

scouring coastal waters in a desperate struggle

to feed their families. But as I traveled the seven

seas, I did not see only doom and gloom. I also

discovered well-managed fisheries that harvest

specific species sustainably, with scientific

monitoring of fish populations to guarantee

long-term abundance. Here was a reminder that

there are solutions, but only if we do a better job

of understanding the sources and impacts of

our food decisions so that we can make more

informed choices. So, the next time you buy

marine life, try to understand how it got to your

local marketplace and remember that even

farmed seafood, like shrimp and salmon, depend

on wild fisheries for their food.

George Steinmetz

The project was partially funded by a grant from the National Geographic Society.

Jonas Manguba, un Bayaka de la république du Congo, a commencé à chasser avec son père dès son plus jeune âge. Dans le cadre d’une initiative de la Wildlife Conservation Society et du Programme de gestion durable de la faune sauvage, les tribus comme celle de Jonas peuvent participer jusqu’à deux fois par mois à des chasses légales et contrôlées en bordure du parc national de Nouabalé-Ndoki. © Brent Stirton / Getty Images pour National Geographic

Ebola, Covid-19, SARS, and monkeypox: zoonotic

diseases occur when pathogens pass from

wild animals to humans, and can develop into

epidemics, or a pandemic.

Millions of people around the world consume

bushmeat which is an important source of food for

many rural communities. It is often perceived to be

healthier and strong cultural beliefs reinforce the

practice. Bushmeat draws high prices and is sold

by hunters, but most is not consumed where the

animals are hunted. After the first sale, the meat

moves to nearby towns where it triples in value,

and there is also international trade on a daily

basis, mostly to African expatriate communities in

Europe, plus a huge market in Asia.

The trafficking of bushmeat to cities to meet

non-essential demand poses a major threat to

many animal species. As urban populations

grow, consumer demand for wild meat increases,

exerting ever greater pressure on wildlife. One

of the largest zones for the trade is the Congo

Basin. Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of

Congo and Brazzaville in the Republic of Congo

are two capital cities separated only by the Congo

River. Combined, they form the third largest urban

agglomeration in Africa, with a total population of

15 million, and by 2050, Kinshasa is forecast to

be the fourth-largest city in the world. According

to a study by the Wildlife Conservation Society,

it is estimated that over 33 thousand metric tons

of bush meat is traded in Kinshasa every year,

making it the hub of this worldwide trade. While

alternative animal protein like beef and chicken is

available in these cities, bushmeat has social and

cultural significance, and is therefore consumed

as a luxury.

As bush meat introduces novel pathogens to

densely populated cities, there is a significant

risk of zoonotic disease, as seen with the case of

fruit bats featured in this report. Epidemiologists

observing camps of fruit bats have found that up

to one-third are positive for Ebola and other viral

hemorrhagic fevers.

The situation is simply not sustainable, and the

land is being stripped of wildlife. Alternatives must

be found, e.g. sustainable fishing, the farming

of weevil larvae, and the new and revolutionary

science of cell-based laboratory-grown meat,

which may be approved for production in the

United States and China.

Brent Stirton

Large portions of this photo essay were shot in

cooperation with the United Nations Food and

Agriculture Organization (Sustainable Wildlife

Management Program).

Goran Tomasevic

Between War and Peace

Today, when words are too often used to conceal

the truth, photography still stands on the side

of reality. A photo speaks the truth. For nearly

two centuries, photography has been the art

that records history forever and keeps us from

forgetting it even if we do not always learn the

lessons we should. In this modern world of

conflict, confrontation and concern for the future

of our planet, photography is more important

than ever. That is what has helped drive me for

the past thirty years when the camera has been

my life. During that time I have helped show the

world what is happening, from the wars in the

Balkans to the War on Terror, to the Arab Spring

and the way that uprising was crushed in Syria.

From Afghanistan to Africa and from Iraq to Latin

America, I have had the chance, and the duty,

to encounter the best and the worst of humanity,

and to record it for all time. Sometimes it has been

dangerous, sometimes it has been beautiful. It

has always been interesting. The pictures here

are only a handful of the tens of thousands that I

have taken. My goal has always been to get close

enough to the action to do justice to the subjects

and to bear witness for those who see the world

through my lens.

Goran Tomasevic