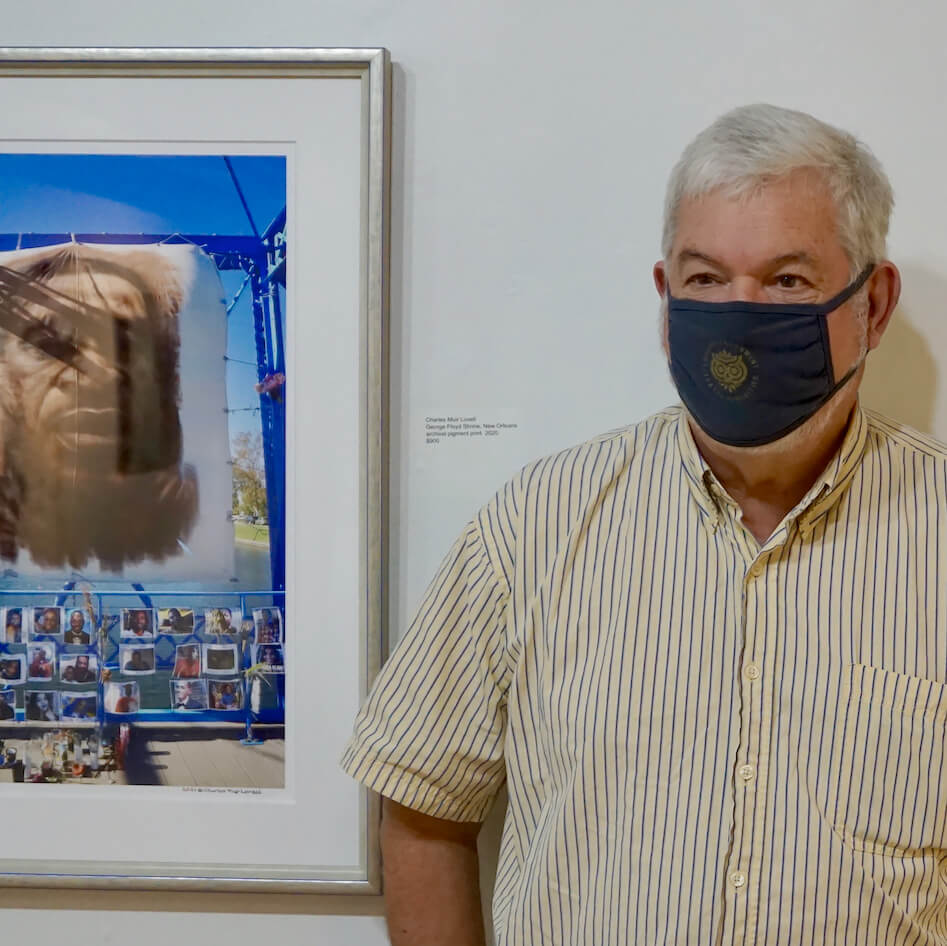

Charles Muir Lovell has long been passionate about photographing people within their cultures. Upon moving to New Orleans in 2008, he began documenting the city's second line parades, social aid and pleasure clubs, jazz funerals, and brass bands, capturing and preserving for posterity a unique and vibrant part of Louisiana's rich cultural heritage. His project

Back When the Good Times Rolled 2009 to 2020 was showcased in

January's 2022 Solo Exhibition. We asked him a few questions about his life and work:

All About Photo: How were you first introduced to the world of photography?

Charles Lovell: My father, Charles Julien Lovell, who was a lexicographer and founding

editor of the first dictionary of Canadian English, owned a small rangefinder

camera he used mostly for taking color transparencies of nature, as he was a

devout hiker in the American and Canadian Rocky Mountains. He gave me

my middle name Muir after the naturalist John Muir. He died when I was

seven, but his pastime inspired my interest in photography. One of my first

attempts was photographing Zsa Zsa Gabor, who was making an appearance

at a Dallas department store. I ended up with a naive candid celebrity shot

taken with an Instamatic camera that was easily forgettable, but somewhat in

the manner of Andy Warhol's Polaroids.

When did you realize that photography was a path you wanted to follow

full-time?

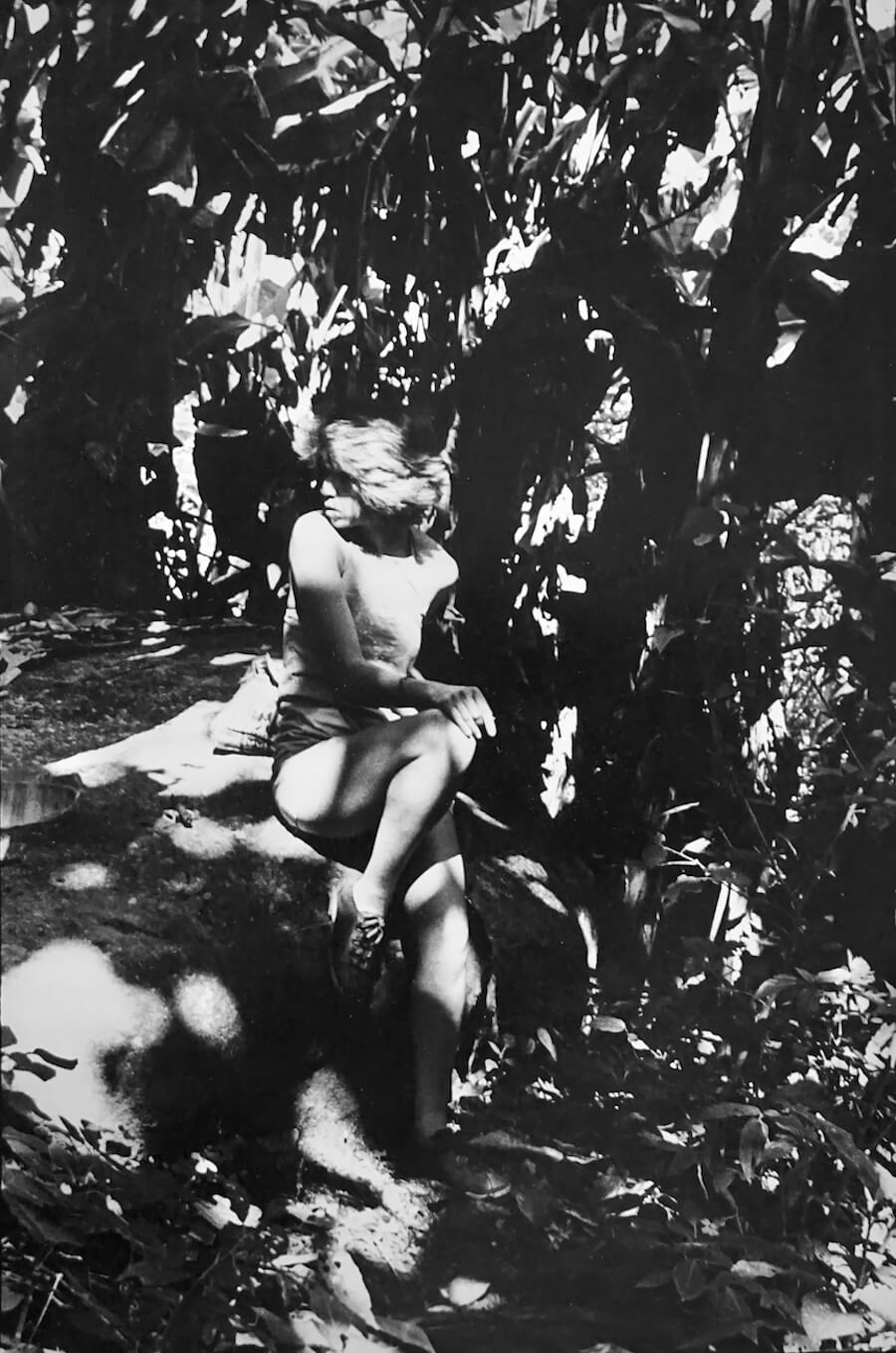

After much soul-searching for a direction during my youth and a time of too

much sex, drugs, and rock and roll, I knew I wanted to see the world. I

bought a Nikon that I took on my travels through South America, and later

Europe. While I was living in Rio de Janeiro in 1973 and teaching English to

Brazilian businessmen and housewives at the Brasas School, I met a model

whose photographer roommate taught me how to develop black and white

film. Upon returning from a trip through England, hiking the Cornwall

coastal footpaths, and traveling in France, Germany and Switzerland,

photographing everywhere I went, I started working for commercial

photofinishers in Dallas - Meisel Photochrome and later the Black & White

Lab - and as an assistant for a commercial photographer, Daniel Barsotti,

who now lives in Santa Fe. All these experiences, combined with wanting to

find a congenial way to make a living, moved me to decide to attend East

Texas State University, now Texas A&M University-Commerce, to study

photography. Before, I had been interested in photography but wasn't

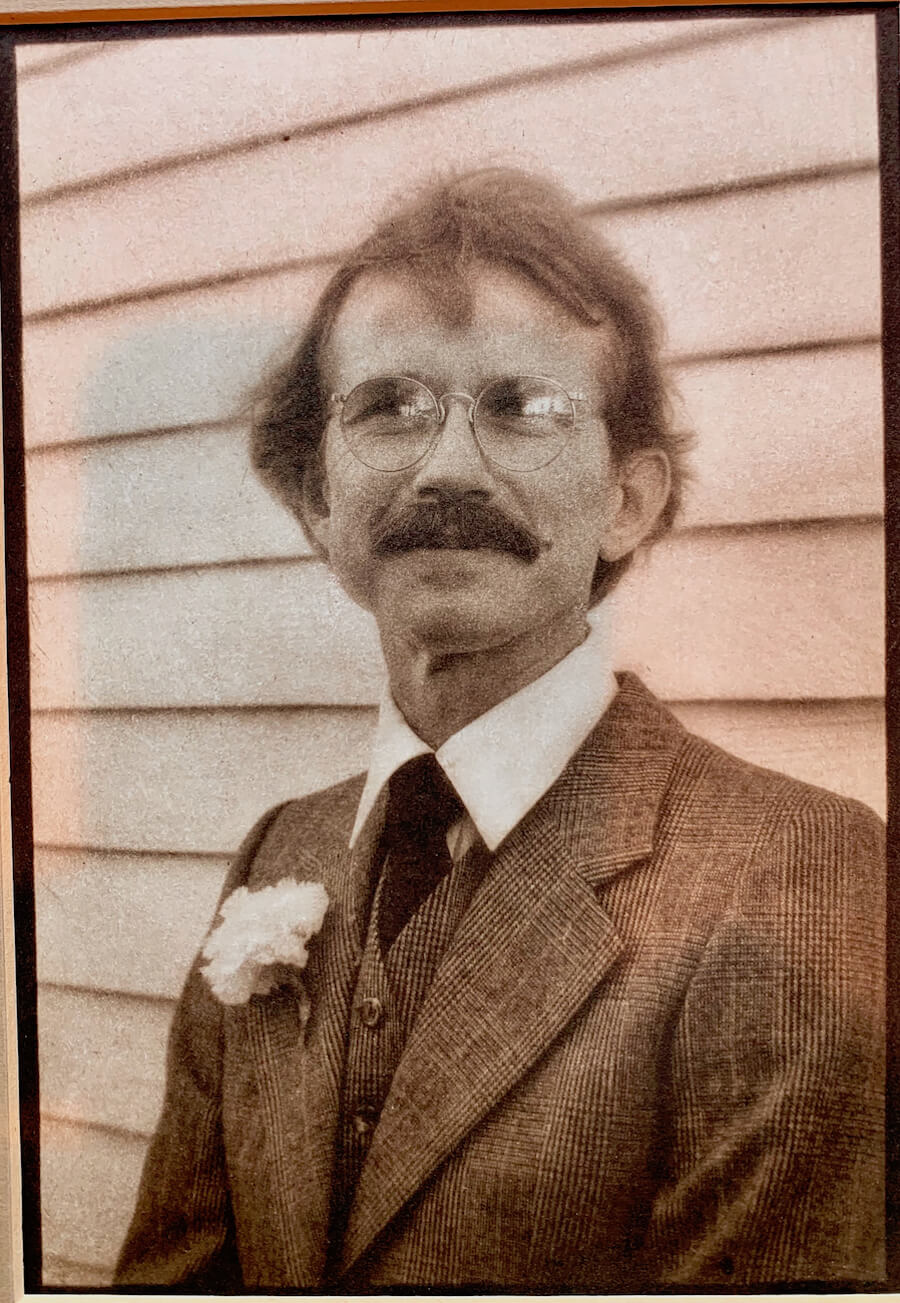

thinking in terms of a career. At East Texas, I studied under professor James

Newberry, who had founded the photography department at Columbia

College in Chicago, and under his influence, I moved from an interest in

commercial photography toward fine art photography. I earned a BS in

photography and started work on a master's degree. I then attended Central

Washington University in Ellensburg where I studied under James

Sahlstrand, who founded the pioneering national photography exhibition

New Photographics.

After graduating with an MFA, I originally wanted to teach

photography at the university level, and after applying for more than 100

jobs, I was finally offered a job by the Ohio State University. I was packing

to move to Columbus when funding for the job fell through, so I switched

my intended career path to museum work. But I continued my photography

during my 20-plus years as a museum director and curator, in the mode of

other photographer/museum professionals like Van Deren Coke and

Beaumont Newhall. My museum career took me all over the United States,

bringing me to New Orleans in 2008. I finally became a full-time

photographer in 2015.

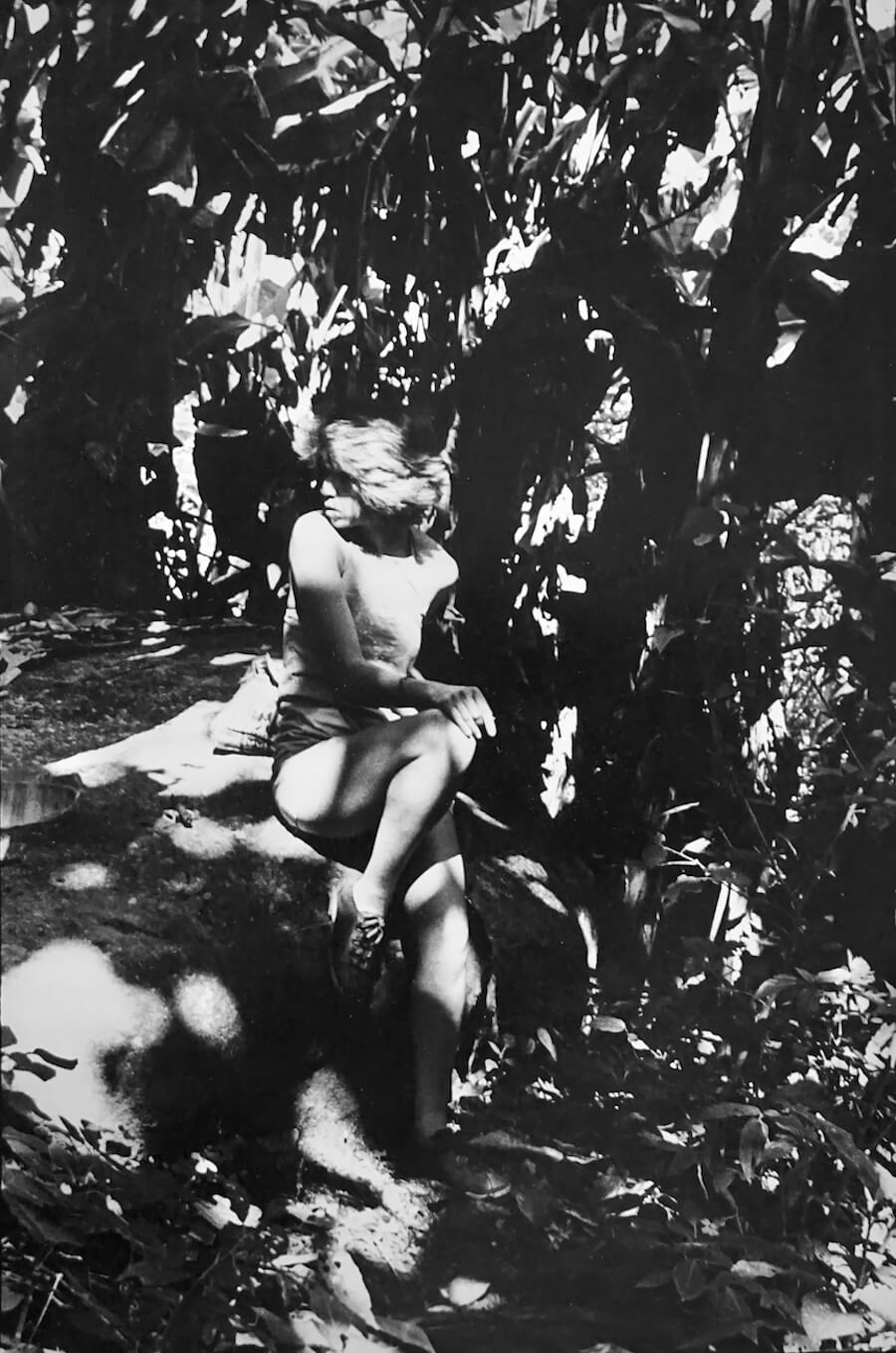

Angela, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1973, Collection of Latin American Library at Tulane University © Charles Muir Lovell

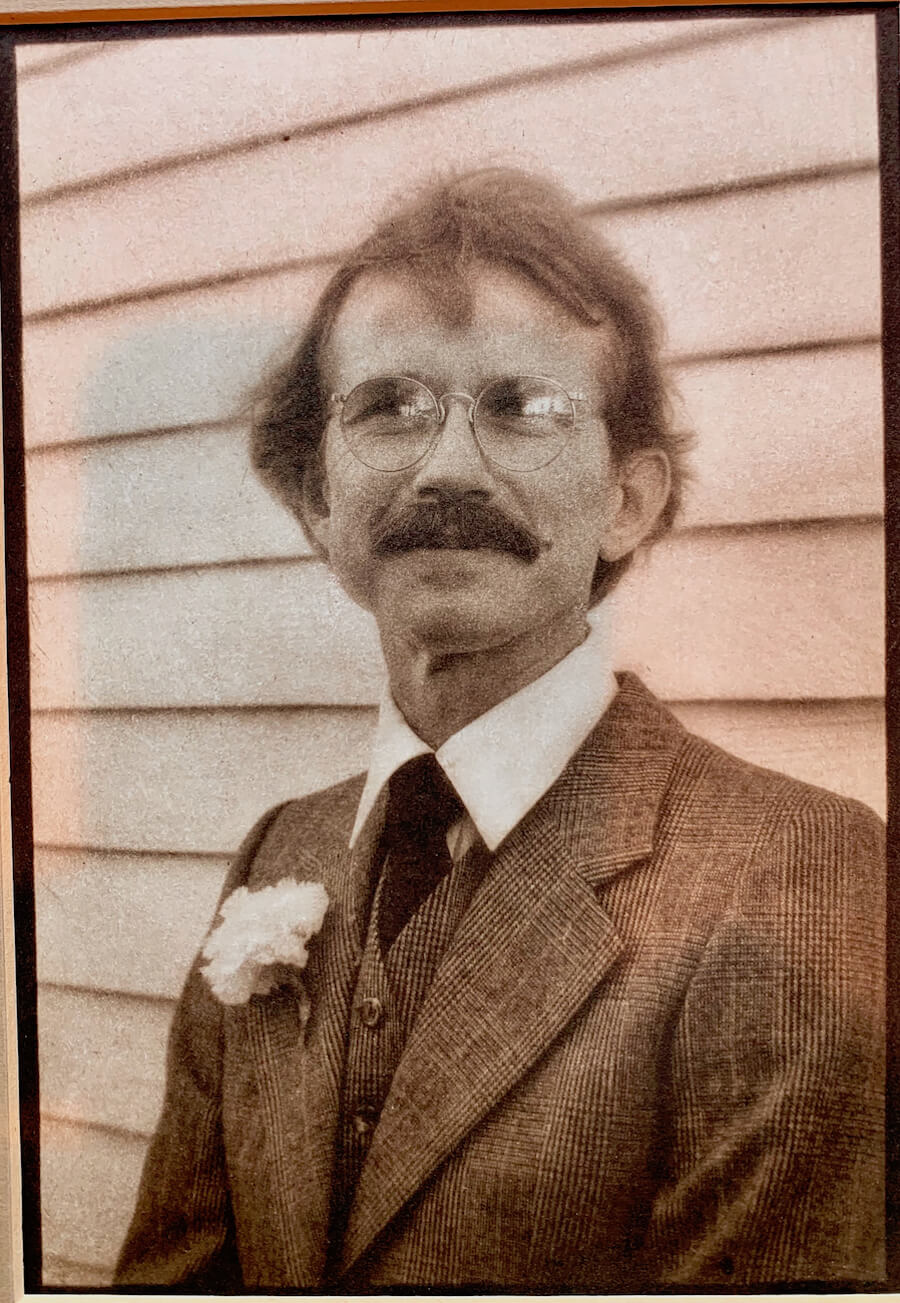

James Newberry at his wedding, Commerce, Texas, 1979, photogravure by Ken Foster, negative and print owned by Texas A&M Commerce Archives © Charles Muir Lovell

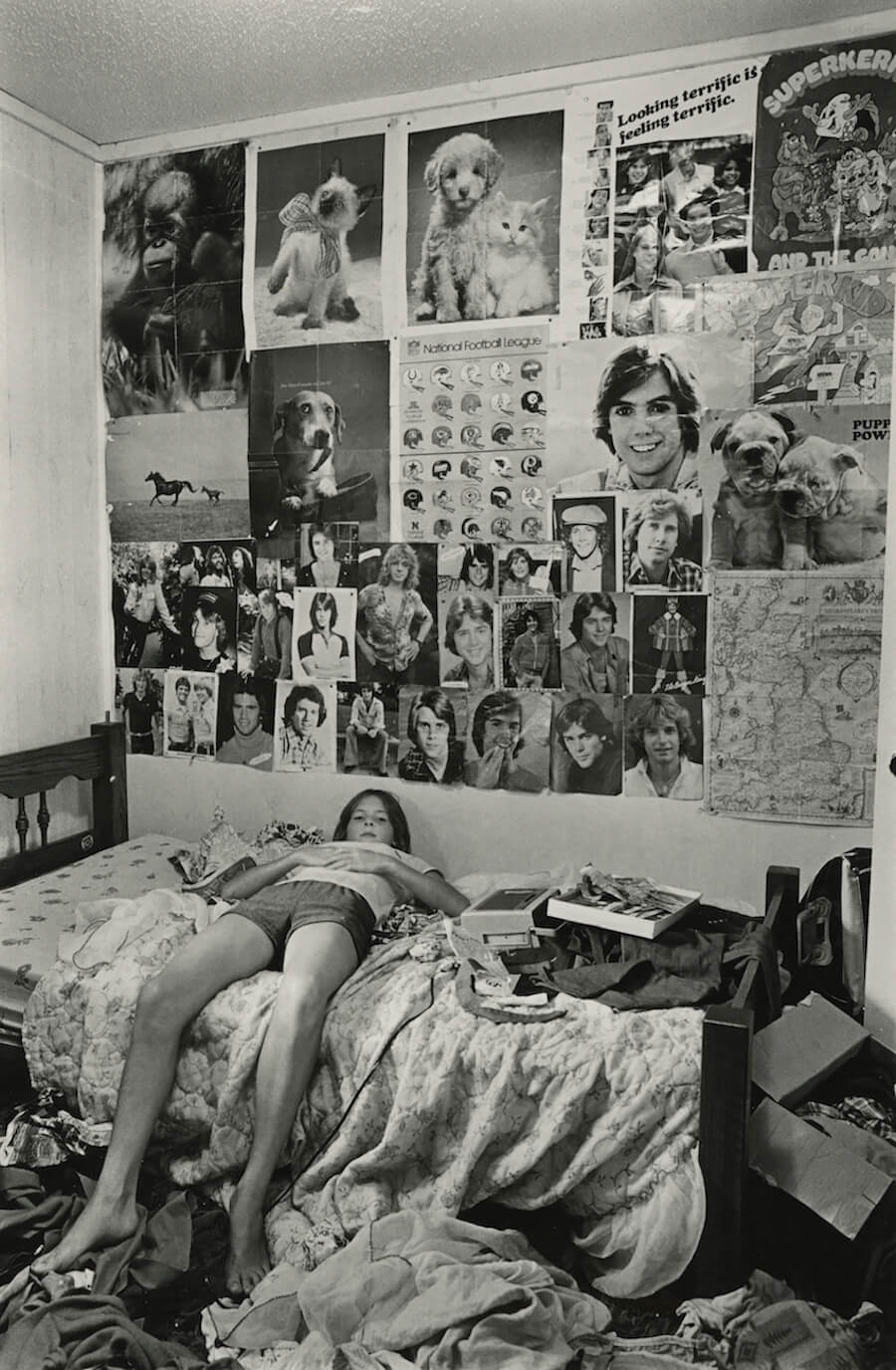

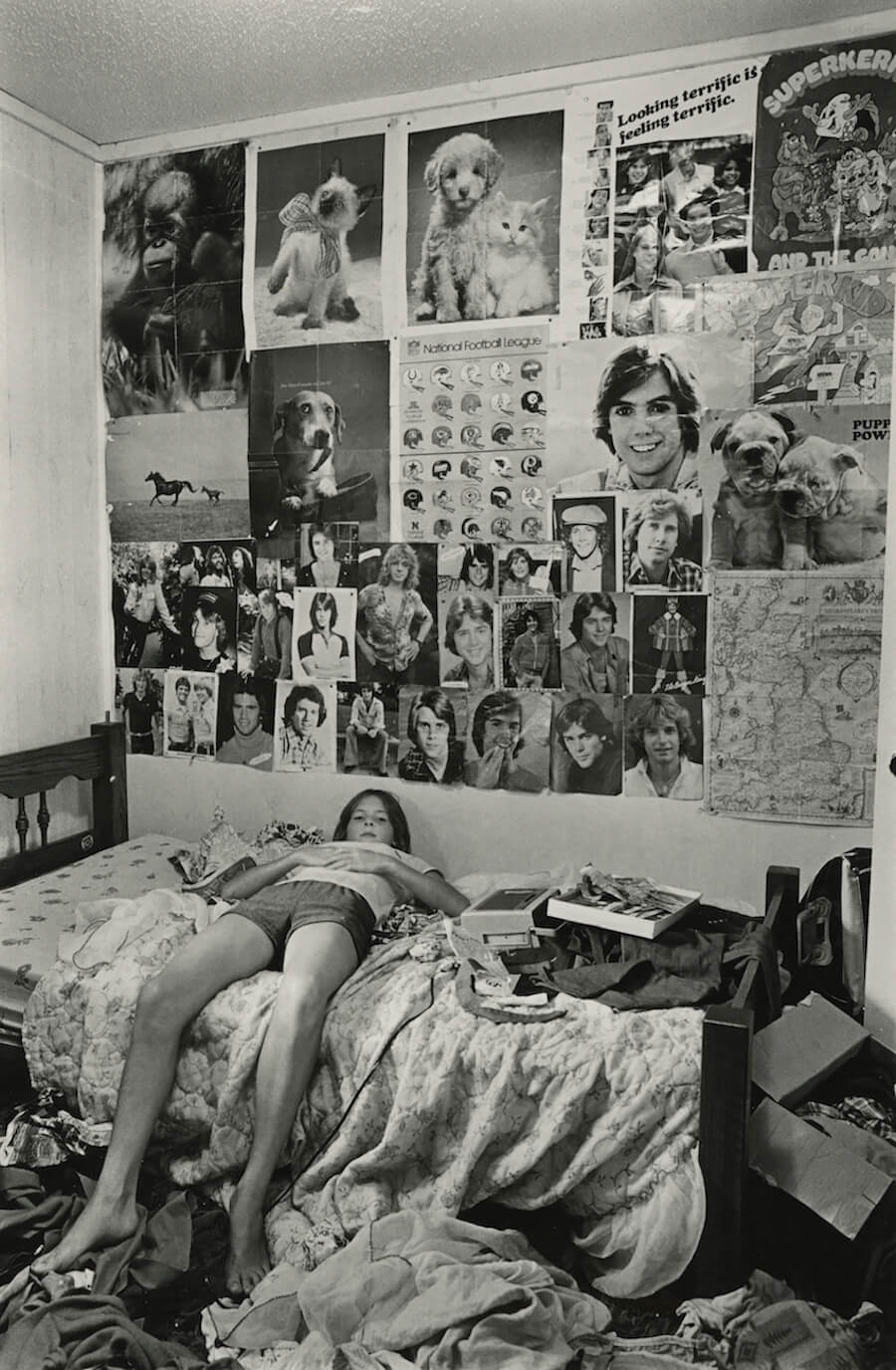

April, Clinton, Oklahoma, 1981, Collection of the Ogden Museum of Southern Art © Charles Muir Lovell

Xenophobia, Venice, Italy, 2007 © Charles Muir Lovell

I love the work of many classic photographers, but I've been especially

influenced by Robert Frank, W. Eugene Smith and Henri Cartier-Bresson.

There have been many important photographers who photographed in New

Orleans and Louisiana whose work I admire, including many of my

contemporary colleagues, such as Eric Waters, Deborah Luster and Dawoud

Bey, to name only a few.

An artist residency at the Emily Harvey Foundation in Venice in 2006

was a turning point in my transition from traditional to digital photography. I

borrowed my wife's small Canon PowerShot camera and took long daily

walks through the six

sestieri, or neighborhoods, of Venice, photographing

what I saw, leaving my large camera at the residence. I liked the results, and

after returning to Taos, N.M., where we lived, I studied and learned digital

photography, which became my main practice after moving to New Orleans.

How has your work evolved over the years?

My early years, which included my practice from 1974 to the 1990s, were

mostly devoted to black and white photography using various formats,

including 35mm, 2¼-inch and 4x5 cameras. During the late 1990s, I had a

grant from the Rockefeller Foundation and support from New Mexico State

University to work on a book on retablos,

Art and Faith in Mexico, and its

associated international traveling exhibition,

El Favor de los Santos. Over

several years, I made eight trips to Mexico where I photographed Holy

Week processions, solely using color transparency film and 35mm and 4x5

cameras. Now I can see the influence of that work on my photography of

cultural traditions and processions in New Orleans, where since 2008 I've

been photographing second line parades and jazz funerals, although now I

use only digital photography. So although my work has evolved from

photographing in black and white to color, and from film to digital, I'm still

drawn to the same subjects and themes. Formerly I used traditional

photographic techniques, but now I have embraced new digital methods,

bringing a fresh approach to my subjects.

Pictograph Wall, Palatki Ruins, Sedona, Arizona, 1991, Collection of the New Orleans Museum of Art © Charles Muir Lovell

San Juan Parangaricutiro cathedral, Michoacan, Mexico, 1992 © Charles Muir Lovell

La Sirena, Baja California Sur, Mexico, 1991 Collection of Latin American Library at Tulane University © Charles Muir Lovell

New Orleans is known as the city where The Good Times Roll. Upon

moving here, I became fascinated by the city's Black cultural tradition of

second line parades. I first encountered one by happenstance in the Treme

neighborhood in the summer of 2009. The Black Men of Labor parade was

in its last half hour, but I was immediately drawn in and followed it to the

end. One of my photographs from that encounter is now in the Historic New

Orleans Collection. I was blown away by the parades - how they express a

vibrant cultural heritage - and became a regular follower. Documenting the

parades photographically became a passion. For more than 12 years, I've

taken tens of thousands of color photographs, so the series is part of an

ongoing body of work. But the Good Times were definitely on hold during

the Covid-19 global pandemic. Second lines were halted for more than a

year starting in March 2020. So that's where the “Back When part of the

title comes in. But now they've resumed once more.

How do people respond to your camera?

I try to blend in with my camera and keep a positive demeanor, but some

subjects are more amenable to being photographed than others. I like to show respect to my subjects and I won't photograph those who object; for

example, a female Masking Indian in a recent procession moved her hand

over her face to indicate she wished not to be photographed. When I'm

photographing second lines, I'm often dancing along in the parades and that

seems to work well with capturing the festivity and mood of the celebration

and relating to the subjects.

What has been your biggest challenge?

Right now I'm working on a book with a Community Partnership Grant

from the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Foundation, and I'm trying to

retroactively find the names of subjects in my photographs. I've tried to

contact all my photographer friends and members and presidents of the

social aid and pleasure clubs and I'm reaching out through social media, but

it's been a slow process, so I am now taking a notepad and pen to future

photo sessions to do a better job of documenting my subjects' names.

Holy Week, Guanajuato, Mexico, 1999 © Charles Muir Lovell

San Juan de los Lagos, Jalisco, Mexico, 1999, in Miracles at the Border exhibition, Princeton University Art Museum, 2021 © Charles Muir Lovell

Young Men Olympian Junior Benevolent Association Second Line, New Orleans, 2011, Collection of the Historic New Orleans Collection © Charles Muir Lovell

Old & Nu Style Fellas Second Line, New Orleans, 2017, Collection of Ogden Museum of Southern Art © Charles Muir Lovell

The book I mentioned will be 100 pages with 80 photographs, a foreword by

Don Marshall, and essays by John Lawrence, Jason Berry and Gwen

Thompkins. I'm also working to launch this project into a national traveling

exhibition. Some of the photographs were featured in your All About Photo

January 2022 solo exhibition,

Back When the Good Times Rolled.

I'm also working on a solo exhibition for PhotoNOLA and the Second

Story Gallery in New Orleans in December that will feature 50 photographs

from my archives, many of which are included in museum collections.

And there is always my ongoing project of photographing second

lines and jazz funerals, as well as a continuing a series of street photography,

The Language of the Streets, which I have photographed primarily in New

Orleans and Venice, where I had another artist residency at the Emily

Harvey Foundation in 2015, and also in Naples, Paris, Mexico City and New

York. Unfortunately, the pandemic caused cancellation of my 2020 Venice

residency.

What equipment do you use?

When I started out in photography, I used Nikon, Leica, Olympus, Rolleiflex

and Linhof cameras using film. Now I'm using Sony, Canon and Fujifilm

cameras, all digital.

Do you spend a lot of time editing your work?

The Covid pandemic was a blessing in that it gave me a great deal of time to

revisit the many thousands of photographs I took from my second line series

since no actual shooting was going on. In normal times, I probably spend 25

percent of my time photographing, 50 percent editing, and 25 percent

marketing and getting the work out there. During the pandemic I spent over

75 percent of my time editing and found many interesting photographs that I

had overlooked in previous editing sessions.

Footwerk Family Second Line, New Orleans, 2019 © Charles Muir Lovell

I would say find your own vision, and stick with it. Photography is the art of

seeing and the ability to share your singular vision with others. With the

advent of phones as cameras, it seems that everyone is now a photographer,

but those previsualized images captured during Henri Cartier-Bresson's

decisive moment are those that stand out above the rest and rise above the

banal.

What mistake should a young photographer avoid?

My first photography teacher at East Texas, Hal Fulgham, advised me that if

you want to make money, go into plumbing, not photography. Like in fine

art, the road to being successful is not often paved with early financial

success, but making good photographs regardless of the financial payoff is a

rewarding experience.

Your best memory as a photographer?

When I moved from a year-round job to a nine-month academic position at

East Carolina University, I spent my first summer of academic leave

photographing in and around Michoacán, Mexico, staying with friends in

Uruapan. High points were visiting the Mexican artist Enrique Luft Pávlata

in Pátzcuaro, sharing stories and mezcal, and two visits to the Parícutin

volcano whose massive lava flow, after burying two villages, miraculously

stopped just outside the San Juan Parangaricutiro cathedral. Two years later,

a solo exhibition,

Imágenes Paradójicas en Blanco y Negro, at the

Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, included some of those

photographs. Many of these works are now in the collection of the Latin

American Library at Tulane University. But when I returned, the university

changed my position from nine to 12 months, which ended the delightful

summers of photography I had expected to enjoy.

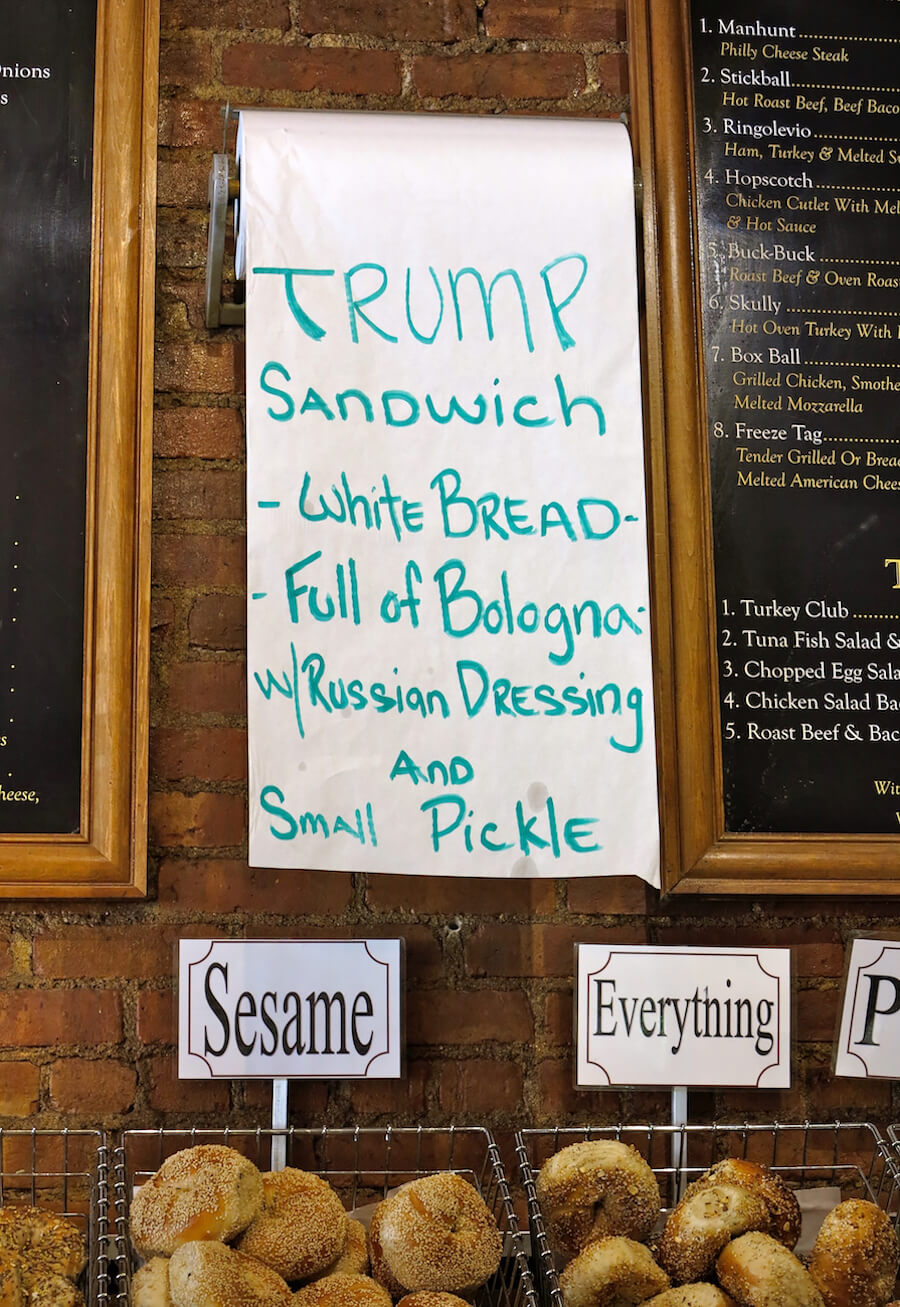

Your worst souvenir as a photographer?

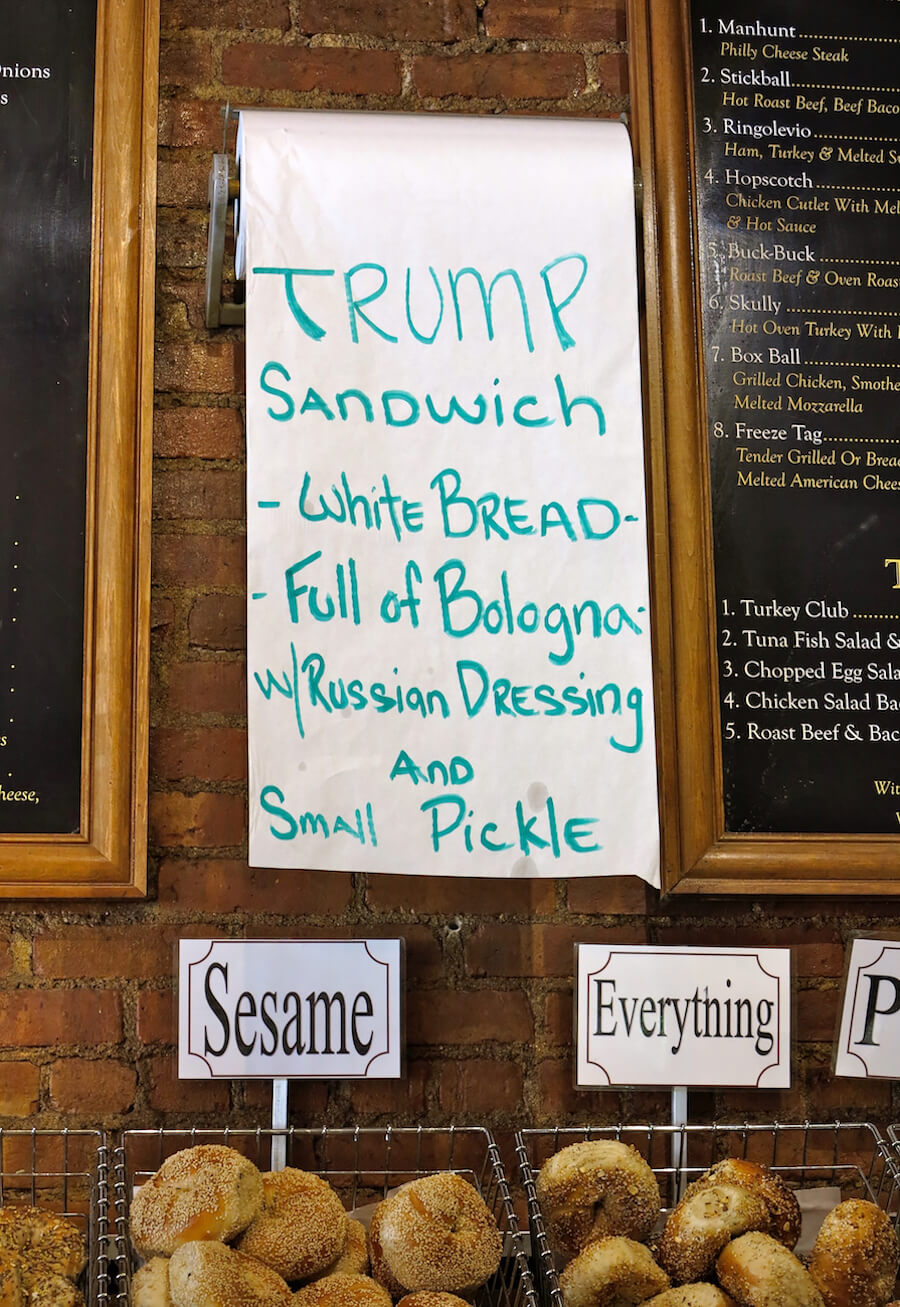

My photo of the Trump Sandwich sign from the Brooklyn Bagel Company

in 2017. The sign says it all:

White bread, full of bologna, w/ Russian

dressing and a small pickle. I never thought this person would ever be

elected to any office and was sure he would have been out of our hair a lot

sooner. I marketed this photograph as a special edition to raise money for

Democratic candidates.

What are your other passions?

I enjoy cooking, hiking and skiing, travel, and dogs and cats.

Anything else you would like to share?

During the past few years I've been donating my photographs to museums

and I'm hopeful other institutions or curators will contact me if they're

interested in acquiring work from my archives, which includes original

prints, negatives and contact sheets of early-career black and white silver

prints taken in Texas and Oklahoma; a surreal period from my graduate

school days in Washington State and the Pacific Northwest; two series in the

desert Southwest and Baja California, one of pictographs and petroglyphs of

Indigenous sites that I photographed with a 4x5 camera, working with

Bureau of Land Management archaeologist Boma Johnson; the other of

photographs from the U.S./Mexico border regions; color transparencies in

the thousands, many of Mexican religious practices and archaeological sites;

and over 100 thousand digital images, mostly documenting New Orleans

cultural traditions, with some of international street photography from my

Language of the Streets series. Museums that have recently added my works

include the Wittliff Collections of Southwestern & Mexican Photography at

Texas State University, the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, the Frances

Lehman Loeb Art Center at Vassar College, the New Orleans Museum of

Art, the Historic New Orleans Collection and the Tacoma Art Museum.

Lower Ninth Steppers Second Line, New Orleans, 2021 © Charles Muir Lovell

Trump Sandwich, Brooklyn Bagel Company, New York, 2017 © Charles Muir Lovell

Banksy, Let G(love)s Be Viral from Covid Series 2021 © Charles Muir Lovell