ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

"SOME PEOPLE" (Every)Body is an international group journalism and art exhibition that examines the ethics, people, processes, and systems that constitute the maintenance of, and barriers to, health for human beings.

Our ongoing live and digital exhibition examines Global Health through the prism of policy, ethics and the need for stable Public Health infrastructure worldwide.

As a group of highly accomplished photographers, artists and essayists, we strive daily through our work toward educated, safe, equitable, just, healthful societies internationally.

With this ongoing multiverse engagement platform we are asking the seminal question of our time: How do people define health, healthcare, and Public Health internationally? What behaviors, values, priorities and business practices need to change now to restore faith in science and in healthcare institutions more broadly? How does political polarization harm Public Health? What is the optimal way to prevent another global pandemic?

While the exhibition celebrates the human body, we also raise questions through visual storytelling and reportage about business practices, persons, products and systems that impose harm to health, and cause death.

What readers experience here is a small except from our live exhibition, which will begin touring again in 2023.

The "SOME PEOPLE" (Every)Body collective is dedicated to education, accountability, evidentiary fact-based reportage, and Tech For Good.

Learn more at

SomePeopleEveryBody.com

Visit us on Instagram

@SomePeopleEveryBody

Subscribe to THE FINE PRINT on

Substack

Children play the board game Life at the Red Cross Shelter at the Monroe Civic Center in Monroe, Louisiana, while waiting for healthcare after Hurricane Katrina, 2005. Essay by Ayanna Buckner, MD, MPH, FACP. / Photo by Miles Boone. Copyright Miles Boone. All Rights Reserved.

I wondered why they didn't understand that they needed the medicine even though they didn't feel sick. Over time, I noticed that people in underserved communities have more health issues and often don't have the financial resources or health literacy to prevent or overcome illnesses as well as people with higher incomes and more education. As I grew older, I learned that people who live in the south are disproportionately impacted by poor health outcomes. This bothered me deeply.

I was drawn to a career in medicine and Public Health because I wanted to address these problems. I later learned that preexisting disparities make people living in the south more prone to the repercussions of floods, hurricanes, and other natural disasters, as well as man-made disasters such as oil spills. I've worked on projects to support healthcare systems in Gulf Coast communities in the aftermath of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. I was frustrated to see so many people without health insurance struggle to get the healthcare they needed after a disaster, while the process was usually easier for people with insurance.

The need for effective solutions to our country's health equity and access issues are heavily based in a social justice imperative, providing the key distinction that qualifies healthcare justice as a fiscal priority in our country.

By Ayanna V. Buckner | Photo by Miles Boone. All Rights Reserved.

www.milesboonephotography.com

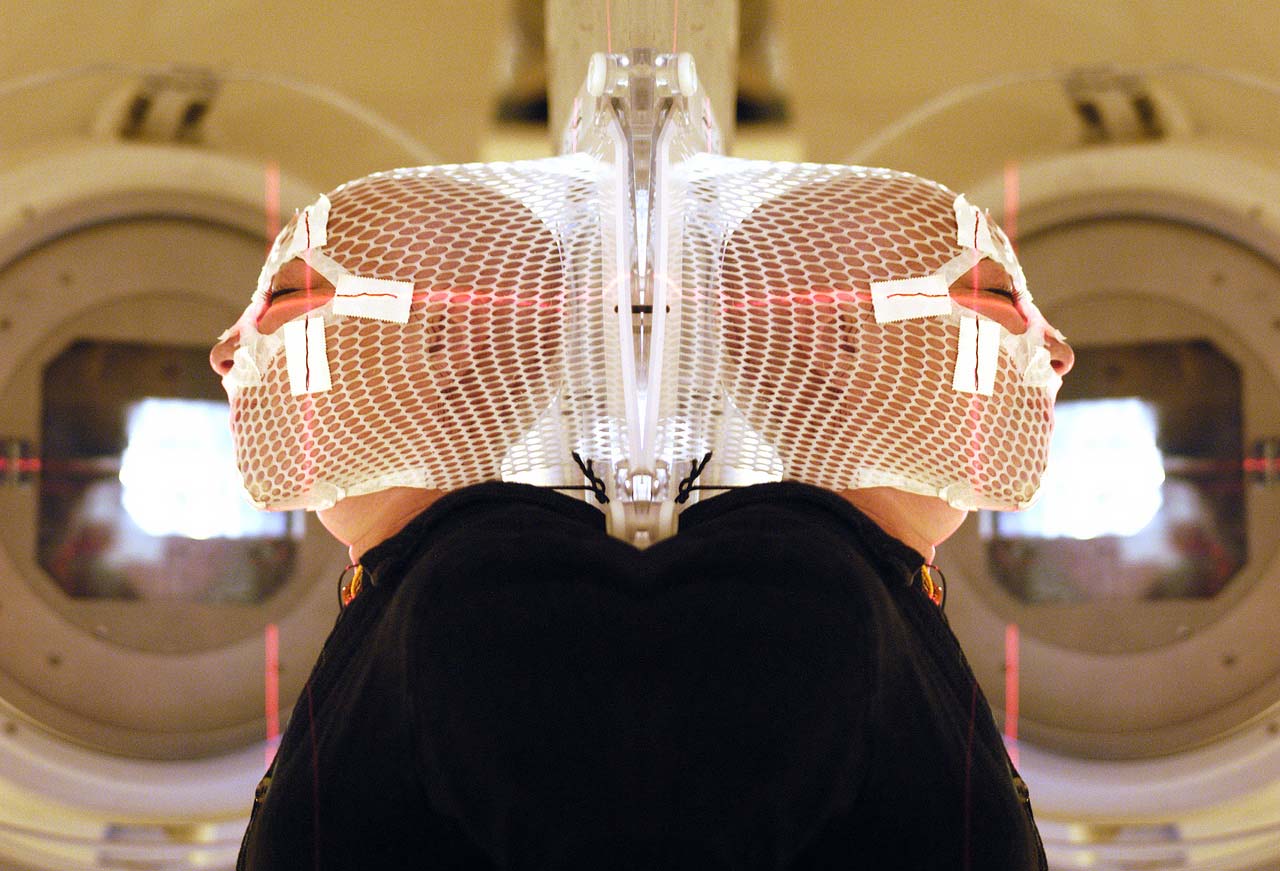

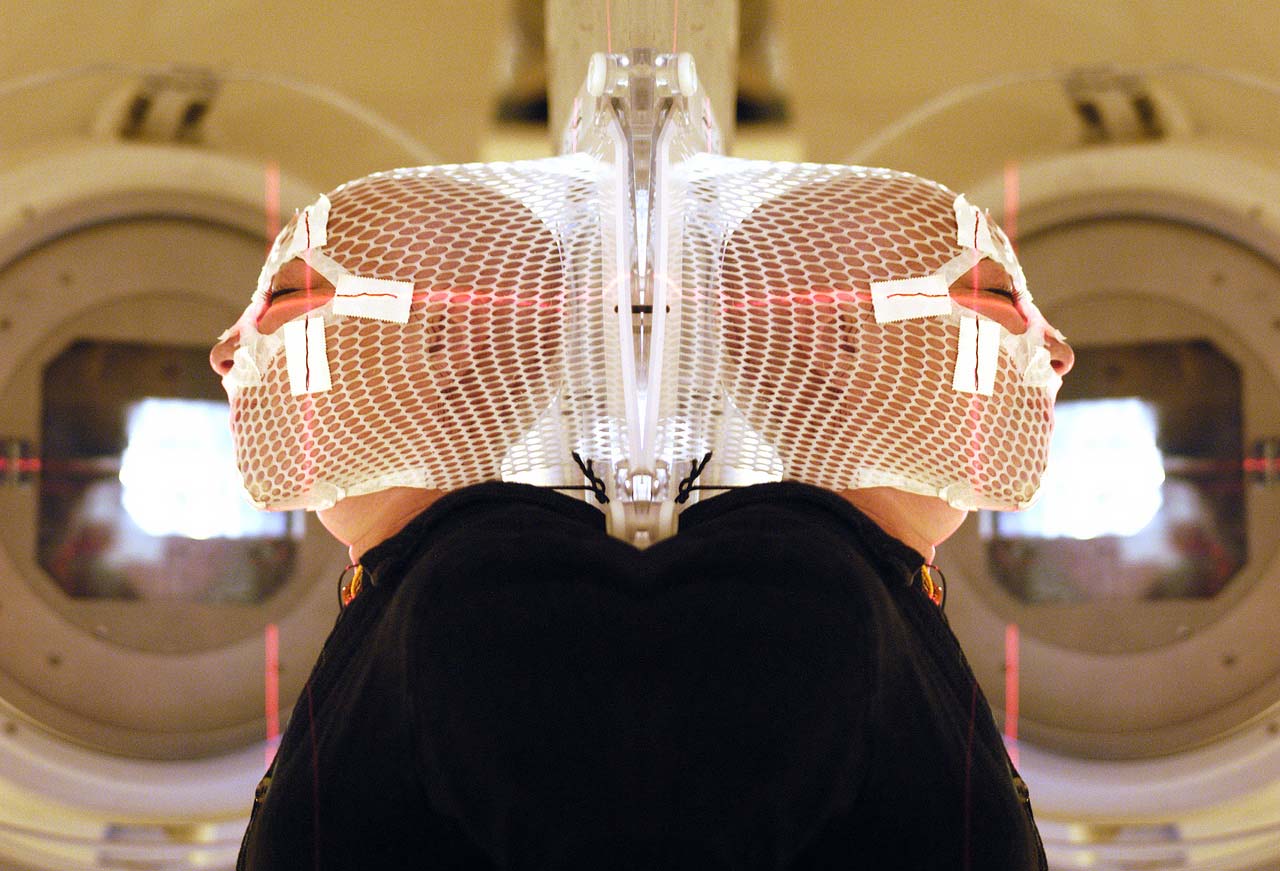

Photo by Heather Perry, All Rights Reserved.

In 2005, while I was pregnant with my son, Finn, now 12, I was diagnosed with stage four Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. I had recognized and ignored early symptoms until it escalated, consuming me from the inside out.

When I finally took the steps to investigate, physicians located a tumor within my pelvis the same size as my unborn son. It was light and a dark shadow in a dance, vying for my body's resources.

I came close to death twice-once from the cancer and once from the treatment. I was lucky.

My husband is a teacher, and in spite of insufficient pay and ever-more challenging working conditions in the United States, one benefit teachers do have is comprehensive health insurance.

The day I was admitted to the hospital, the oncology nurse on staff at our insurance company actually called me to give me her direct phone line and let me know that she would be our personal support, liaison, and guide with any billing and health insurance issues. With great relief, this gave us the peace of mind to not worry about what this would do to us financially-it stretched us but didn't break us-and focus on my care and wellness.

After months of extensive chemotherapy and radiation treatments, and countless invasive procedures, it was determined that a stem cell transplant was required to save my life. An intense and extreme procedure, my husband and I knew that the road would be emotionally, physiologically, and financially taxing.

When my oncologist walked in to introduce the idea of a stem cell transplant to me, her first words were, "How good is your health insurance?" Imagine. "How good is your health insurance?" That was the first question before explaining the costly but necessary procedure required to save my life.

Because of my husband's private health insurance plan, we didn't have to hesitate. We were lucky. We experienced no health insurance complications or denials. We went forward with every recommended scan, blood draw, biopsy, consultation, medication, and appointment that my physicians ordered.

Eventually, I was prescribed Neupogen, an injection I had to give to myself twice a day for weeks. The cost, I later learned, was $2,000 per syringe. I once left the pharmacy with a pack of 20 syringes. I saw waves of bills for thousands and thousands of dollars. Thankfully, I was never rejected.

All told, my care, including the premature birth and neonatal intensive care of my son, all of my cancer treatment and follow-ups (which lasted a decade before I chose to stop), came to somewhere in the neighborhood of $1.5 million.

The financial cost to us, while insured, was about $15,000 over that time period. If it hadn't been for our health insurance, I'd be dead and my husband and son would be bankrupted by medical bill debt. I believe this.

I never asked why my body made a single cellular misstep, which propagated and threatened my life. Why not me? But what I do ask is: Why is healthcare connected to my husband's job as a teacher-employment-instead of my life as a human?

In a country that doesn't grant healthcare as a human right, I was among the lucky few who had the right answer to the question my oncologist asked me that day, "How good is your health insurance?"

I am grateful for the ways cancer changed me. I am grateful for the care I received by healthcare professionals, friends, family, and many strangers who took me in their arms and cradled my family through this scary-wonderful time.

I am grateful for water, where I went to heal. I could swim before I could walk again, and I'm still swimming today.

I think of water as a ubiquitous nurturing source...it carries us, nurtures us, and peels away our layers to reveal the very purest form of who we are. It costs nothing to let it do its good work on us. And I never take that for granted.

By Heather Perry | Photo by Heather Perry, All Rights Reserved.

www.heatherperryphoto.com

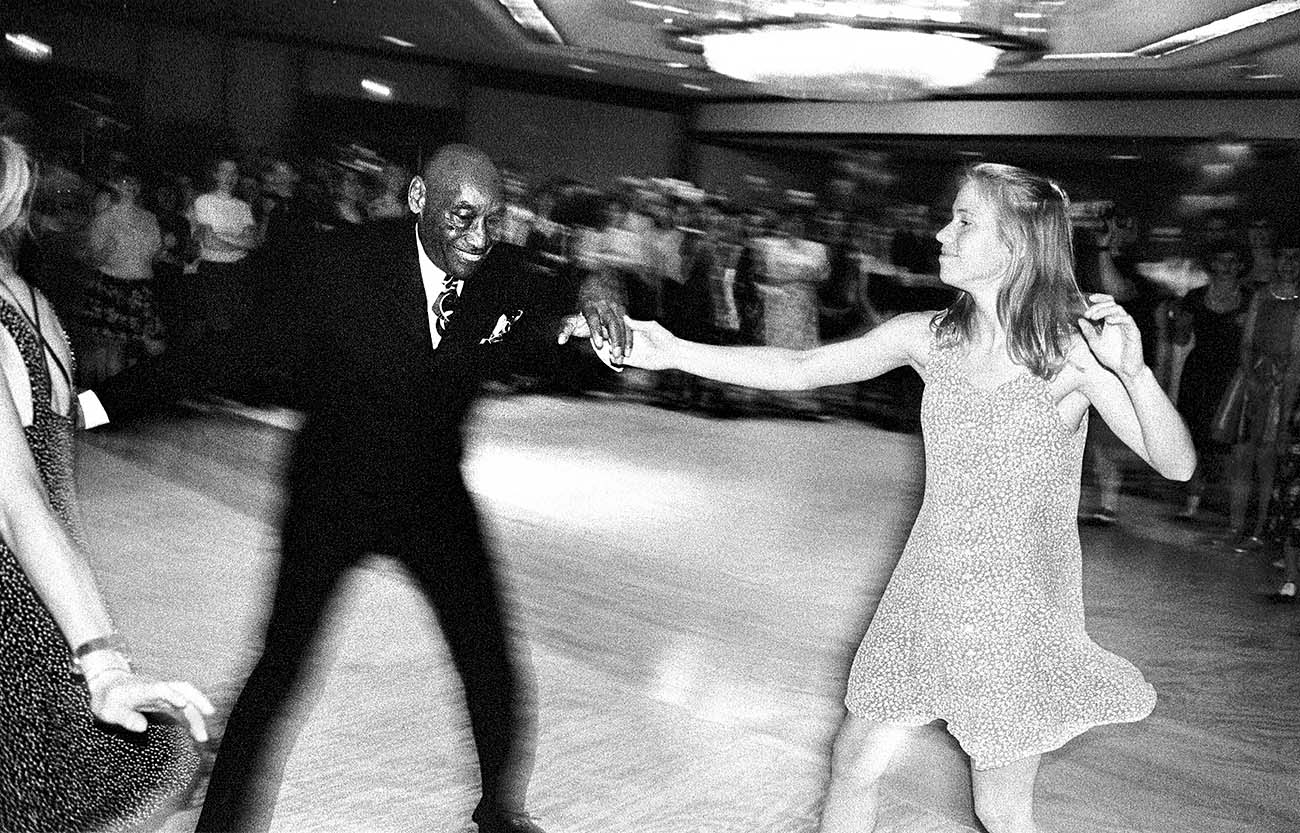

From Aging in America: The Years Ahead, 2003. Photo by Ed Kashi/VII. All Rights Reserved..

Jahmel Tarver, 27, became a quadriplegic and remains in a coma after complications from surgery for a torn Achilles tendon. Tarver is the former quarterback for the Troy Fighting Irish, a semipro football team in New York. Photo by Misha Friedman.All Rights Reserved.

Dr. Roberta Miller hits the road daily to do house calls like this one at 8:00 a.m. Many people are too old, injured, or sick to travel to the doctor, so Dr. Miller comes to them. Home visits make a different kind of care possible. She's put in 250,000 miles on her Honda minivan going to their homes in upstate New York. Dr. Miller runs a private practice that provides a very important service. For her patients, her house calls prevent and minimize many unnecessary visits to the emergency room.

My initial motivation for this series about Dr. Miller was to cover both urban and rural house calls in and around Albany. It's a misconception that only rural patients require house calls.

I shot a feature in South Dakota about access to healthcare for Native Americans and my intention was to report on the modern version of the country doctor. Since the escalation of managed care and the rise in power of the Health Insurance Association of America over the last 50 years, doctors have stopped doing house calls for the most part, so I set out to document who these country doctors are now and where the gaps in care exist today.

As a journalist I've witnessed the many ways in which the US system is still failing. One contributing factor is that so many medical students choose to specialize in dermatology or gynecology, for example, because compensation is generally more competitive in those areas of practice. Becoming a geriatrician, primary care physician, or family doctor is not as sexy or profitable, and earning potential is an enormous consideration when physicians are starting out, saddled with astronomical debt, straight out of medical schools/residency.

What did I notice while documenting house calls? For many of the patients, house call doctors act as a lot more than a doctor. They also serve as a friend, psychologist, nutritionist, and much, much more for their patients.

Misha Friedman | Photo by Misha Friedman. All Rights Reserved.

mishafriedman.com

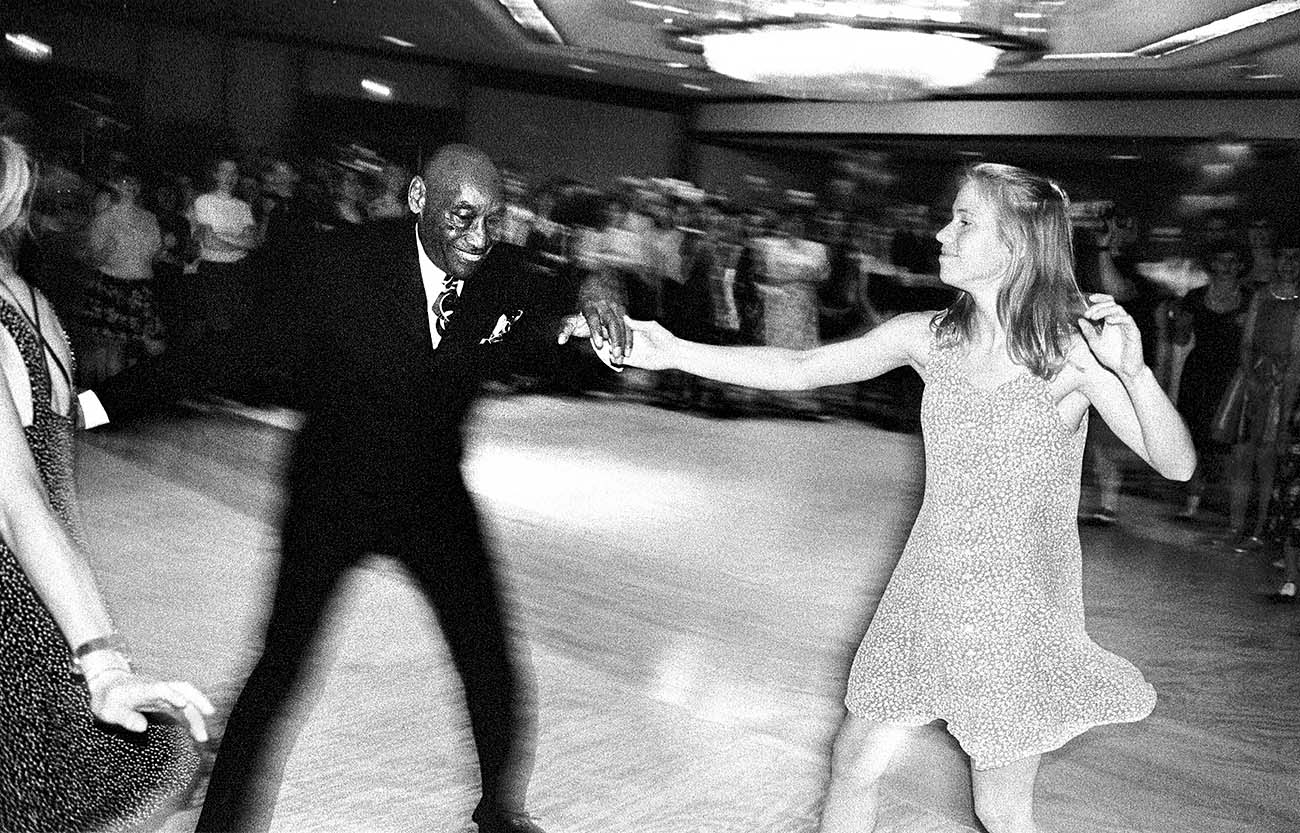

Boxer. Austin Boxing Club in Chicago. Photo by Doug McGoldrick. All Rights Reseved.

When I arrived at the gym the first time, I was astonished by what I learned. All of my preconceived notions of what to expect dissolved. This wasn't just any gym, it is a gym that runs on donations, and most people who go don't donate anything. A man named Sal Ahmed supports the entire operation almost entirely by himself. The area of Chicago that this gym is in is an area that doesn't have a lot of options for exercise. People talk about food deserts, but there are also deserts for other things as well: places to exercise, health clinics, community centers, libraries, grocery stores, banks, playgrounds, and schools. This gym fills a void in the area. This gym gives people a space to go to learn a skill and exercise. The gym's motto is "Gloves Up, Guns Down."

What I learned is that Austin Boxing Club is actually a health center. The gym provides a place to exercise, it's a social gathering center, a brotherhood/sisterhood, a safe space and a community center; it's a place to talk about what's going on in the community, a place to congregate, a place to sweat, and a place to challenge yourself with trusted mentors. It's a place to study and learn.

All of that right there in the middle of what would be called a "desert" at 5915 West Division Street in Chicago.

Sometimes when you're driving by, on "the outside," it's easy to pass judgment, have prejudice, or experience fear about a place, some people, or "other." For me, as a photographer, curiosity always serves me better than fear.

A funny thing happened as I began shooting there two years ago. I started boxing and working out there, too.

By Doug McGoldrick | Photo by Doug McGoldrick. All Rights Reserved.

dougphoto.com

Photo by Jean-Marc Giboux. All Rights Reserved.

Photo by Paul Gilmore. All Rights Reserved.

Mother with medically-complex child. UNC Hospitals Children's Specialty Center in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.. Photo Matt Eich. All Rights Reserved.

I managed to maintain my composure during the job, but after returning home I broke down and cried like a baby, my heart breaking for what this family has already been through and has yet to face. I'm very grateful to the families that are open, and vulnerable enough, to share their struggles with strangers.

By Matt Eich | Photo by Matt Eich. All Rights Reserved.

www.matteichphoto.com

Remote Area Medical temporary clinic. Knoxville, Tennessee, 2016. Photo by Timothy Fadek.. Photo Timothy Fadek. All Rights Reserved.

In 1965, United States President Lyndon Johnson introduced Medicare for the elderly and Medicaid for "the poor," and then there was everyone else in between. At that time, out-of- pocket direct care from doctors and hospitals was relatively affordable. When a need arose, we simply dipped into our savings to pay for medical services and medicine.

Today it's a completely different experience. If you're not wealthy or cannot afford private health insurance, healthcare and medicine are so expensive, people are bankrupted after just a few weeks in the hospital or if they require medicine over the long term.

This is the gamble that many of America's "working poor" are making. They are in-between. They earn too much to qualify for Medicaid but not enough to afford private health insurance. To make matters worse, doctors have closed their offices in impoverished areas of the United States-mostly rural-because physicians can no longer afford to run a practice there.

This leaves patients with no options. Because the health insurance industry and hospital chains cannot extract exorbitant profits in these regions, more than 70 rural hospitals have closed across the United States since 2010. As of 2019, 673 additional rural hospitals are considered "vulnerable or at risk for closure." Among the hardest hit regions in the United States: Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia in Appalachia.

In 1985, Remote Area Medical (known globally as RAM), was founded by the late Englishman Stan Brock. In 2016, I photographed one of the RAM mobile clinics set up in a convention center in Knoxville, Tennessee. As a journalist, I was acutely aware of the disparity and ever-growing financial divide in the US, but it still surprised me to learn that Americans needed to rely on a charity that was originally conceived to treat people in the less-resourced countries of the world, natural disaster aftermath areas, and conflict zones.

Upon arriving, I saw close to a hundred cars in the parking lot, filled with entire families who had queued for days in the cold just to see doctors and dentists. Some cars had as many as five people sitting inside. RAM even gave away old used glasses for people with vision needs. Some license plates were from the neighboring states of Georgia and Mississippi; these were families that drove hundreds of miles to seek medical care...in the United States.

Hundreds more people without cars were queued up, huddling together under blankets in the bitter cold. They waited in the dark predawn hours until the gates to the convention center were opened to them at 5:00 a.m.

This scene was no different than the refugee camps I had photographed along the Syria-Iraq border, or the post-earthquake camps in Haiti, or the food lines in war-torn Kosovo, or refugees of Libya streaming into Tunisia.

America is a country rich in medical advances, but it's also a country where tens of thousands of people die every year due to a lack of health insurance.

The 2020 presidential election campaigns will surely see candidates from both parties make healthcare an election issue, but it's unclear whether voters would support the concept of universal healthcare, even though most have come to accept the notion that healthcare is a human right..

By Timothy Fadek | Photo by Timothy Fadek. All Rights Reserved.

www.timothyfadek.com

'It used to read Welcome to Pepsi country.' Highway 89 outside of Tuba City near the Moenkopi Arroyo, Navajo Nation, Arizona, 1987. Photo Chip Thomas. All Rights Reserved.

Today, people on the Navajo Nation, where I've practiced medicine and called home for more than 30 years, suffer from an array of preventable illnesses.

I had been living and practicing on the Navajo reservation for one year when the Pepsi Corporation erected a billboard enticing motorists to drink their ice-cold sugary beverages. It was impossible to ignore the bold, large-scale advertisement. As much as I wanted to imagine its primary audience was for nonindigenous tourists traveling from Phoenix to Lake Powell, the billboard was located in one of the regions with the highest Type 2 diabetes mellitus rates in the country. The billboard was up for several months when Laurie Smith, a Public Health nurse colleague of mine, and I discussed our shared frustration at the insensitivity of the advertisement and disregard by Pepsi.

The Pepsi billboard was advertising sugary drinks in a community that, at that time, had the highest per capita consumption of soft drinks and Spam. The area was considered a food desert and obesity was prevalent; the community also had the highest per capita sales of Kentucky Fried Chicken. The endless and aggressive advertising of these "food products" presented the perfect opportunity for us, as community-responsive health practitioners, to challenge this insensitivity.

In 2016, the United States soft drinks market was valued at $253.7 billion. These sugary drinks are nonalcoholic but contain flavoring, white sugar, and sometimes additional sweeteners which perpetuate the alarming diabetes epidemic in the United States. In many regions globally, sugary drinks are easier to access than clean drinking water.

As physicians and nurses, even back then, we were acutely aware of the high incidence of Type 2 diabetes among people on the reservation and the consequent complications associated with the chronic illness, such as leg amputations, renal disease, blindness, and heart disease. Renal disease makes people dialysis-dependent, which takes an emotional and financial toll on patients. Indigenous communities have the highest rate of Type 2 diabetes mellitus of any group in the country. The illness affects 25 percent of the adults over the age of 45 years. By comparison only 1/12 of Caucasian Americans develop this chronic illness.

We wanted the Pepsi Corporation to consider the impact their products make on high-risk communities who are living in food deserts. We were hoping to prompt people most impacted by the harm sugary drinks cause to reconsider the impact of their "food" choices. So late one night in 1987, we, a doctor and nurse no longer willing to accept the deceit of Pepsi and like-minded corporations, climbed up on the billboard and corrected it to read "Welcome to Diabetes country." It used to read "Welcome to Pepsi Country."

By Chip Thomas | Photo by Chip Thomas. All Rights Reserved.

jetsonorama.net

Spirit Walker, a fifth-generation descendant of Chief Black Hawk, waits for healthcare at the Remote Area Medical pop-up clinic in Wise, Virginia. Photo Justin Merriman. All Rights Reserved.

Here, Spirit Walker, a fifth-generation descendant of Chief Black Hawk, sits in the cinder block animal stables at the Wise County Fairgrounds in Virginia, waiting to be seen by a doctor. His shoulders hunched, hands on his knees, he wears an "I Love Jesus" baseball cap with an American flag pin on it. Sheets hang from clothespins, providing a thin veil of privacy between him and the more than 2,000 other people who traveled from 15 states seeking free medical care.

Today, the fairground doesn't host rodeos or pageants; instead, it is the location of the largest pop-up healthcare clinic in the United States.

Each morning, long before the sun crests the surrounding mountains, families line up at a gate with a numbered ticket in hand, waiting for their chance to enter. For many, this is their only chance to see a doctor, get much needed dental work, or get fitted for glasses. The parking lot becomes a campground, where many spend the days sleeping in their cars, in tents, and on the bare ground. I joined them as I slept in my own tent on the edge of the field.

My camera catches glimpses of people's faces as they stand in line in the dim light of cold mornings. The exhaustion of waiting weighs heavily in their eyes. The scene is surprisingly quiet.

"I'm 55 years old. I've tried to get Obamacare. For me, it would be $800 a month. There's no way to afford health insurance and there's no way to live without it," says Murleen Smith, of Big Stone Gap, Virginia, who has made the trek to RAM for four years now. Murleen says she counts on the clinic. "Basically, you wait all year for this healthcare clinic to come around."

By Justin Merriman | Photo by Justin Merriman. All Rights Reserved.

www.justinmerriman.com

Photo by Lloyd Degrane. All Rights Reserved.

Photo by Lloyd Degrane. All Rights Reserved.

Photo by Lloyd Degrane. All Rights Reserved.

Mostly, I look at myself as a curious man who has walked the streets of downtown Chicago for four years outfitted with a backpack filled with syringes, cigarettes, bandages, a notebook, food, an audio recorder, and my camera.

My wife tells me I've probably walked about 5,000 miles while documenting "my people," as she likes to call the homeless people I've gotten to know over the years.

Four years ago, I began documenting the connection between addiction and homelessness as a photojournalist.

Homeless persons need help surviving in their very desperate, violent, and dangerous world. I've worked on stories for The Guardian, The Chicago Tribune, The Reader (Chicago), and electronic news services of all sorts. But now, I make photos as a testament, as a witness to this unprecedented and horrific opioid addiction epidemic. I also advocate for people. On the streets of Chicago, I've administered Narcan, I've brought people to the emergency room, I've given them food.

My backpack shows signs of wear these days, as do my mind and heart. It's been in the rain, humidity, Chicago wind, hot summer sun, and the brutal sub-zero polar vortexes of Chicago's extremely long and punishing winters. The street folks who I document have also been through those same conditions-and they, too, are weary.

To get some type of understanding about homelessness and its causes, you have to explore the streets, the alleys, the doorways, the crevasses, and corners. You have to be with the people, walk with them, talk with them...and that requires time...lots and lots of time.

Sometimes I capture a good photo, oftentimes I do not. But I keep coming back. They need to be seen.

So I'll keep coming back.

By Lloyd Degrane | Photo by Lloyd Degrane. All Rights Reserved.

lloyddegrane.com

United States Army Sergeant Chris Kurtz in his home, December 2018. Photo by Erica Brechtelsbaur. All Rights Reserved.

I first met Sgt. Kurtz when he was arriving home from a day of work in December 2018; I was photographing a story for NPR about the United States Veteran Administration's Family Caregiver program. The Kurtz family, along with many others throughout Tennessee, had been arbitrarily cut off from the program. For years, Chris and his wife, Heather Kurtz, had received the highest level of support, Tier 3, which included a stipend for Heather's caregiver status and healthcare, as well as quarterly visits from a nurse. In July of 2018, Heather was informed her status was being reevaluated and, without notice, they were dropped from the program entirely.

Chris is reflective, positive, caring, and to the point. Because of his amputations, he's dependent on Heather for simple tasks. Putting on prosthetics is a time-consuming task. Heather frequently tends to the sores prosthetics cause. After the cut in funding, Heather returned to work as a school aid, which diminished her time to care for Chris. The financial distress that's been imposed on the family weighs heavily.

During the course of the day, I realized I had unconsciously stereotyped Chris prior to meeting him. I had expected the mood in the room to be overwhelmingly sad. How could this man, a man who faced death in war and lost multiple limbs still joke around and remain positive?

I am lucky that I do not have any physical disabilities. I've always been acutely aware of my own health, as diabetes and autoimmune diseases run prominently throughout my own family. I also manage anxiety, so I understand the degree to which compromised health can disrupt life. In my work, I am endlessly considering the inexplicable factors of chance, circumstance, and luck.

By Erica Brechtelsbaur | Photo by Erica Brechtelsbaur. All Rights Reserved.

Siblings meet for the first time. Woman giving birth in water. Photo by Marijke Thoen. All Rights Reserved.

In Belgium, we have universal healthcare, so access and affordability are not an issue here. That layer of financial distress or insurance coverage-worry while pregnant does not exist.

Many women globally receive the message that birth is something to fear. In certain cultures and contexts, including in the United States, pregnancy and childbirth are still considered a disability, handicap, or illness.

I feel humbled when parents allow me to witness this miracle over and over again. Sometimes I am not sure if my photography is about showing mothers how incredibly strong and powerful they are, how strong their bodies are, or if it's about showing these newborns, when they grow older, the gentle loving care they were showered with when they were welcomed earth-side, as I call it.

As a single mother of two children, I wish every soul could see with their own eyes how much love was rained down upon them when they entered this world. If everybody saw that, how could anyone one ever doubt that they are loved? That the body and being are to be respected, revered, and honored?

When I am witnessing and documenting births, people forget entirely that I am in the room. Emotions are raw and time seems to slow. I've never witnessed something go severely wrong, but I can say from considerable experience that birth rarely goes according to plan. These little ones each come into the world in their own way, on their own time, which is often very different from the wishes or expectations mothers have about their deliveries.

My son was born at home on the bathroom floor. Within half an hour of going into active labor, I birthed him on my own because my midwife was unable to arrive in time. Looking back on it, I was stunned that my body just knew what to do to deliver him.

That's the amazing thing about women, about mothers: we just know what to do. Sometimes I think we forget how to trust the wisdom of our bodies.

Giving birth is also a process where you cross your own boundaries, and the amount of pain you thought you were capable of coping with, more than once. But as soon as that baby lies in your arms, you are determined you are going to protect "this thing you went through so much pain for" with everything you've got.

Becoming a mother changed me. It brought me back in touch with who I really am and confirmed for me the reason I am here. The first thought that came to me after I had given birth to my daughter at the age of 29 was, "Oh...so this is who I am. I am a mother."

By Marijke Thoen | Photo by Marijke Thoen. All Rights Reserved.

www.marijkethoen.be

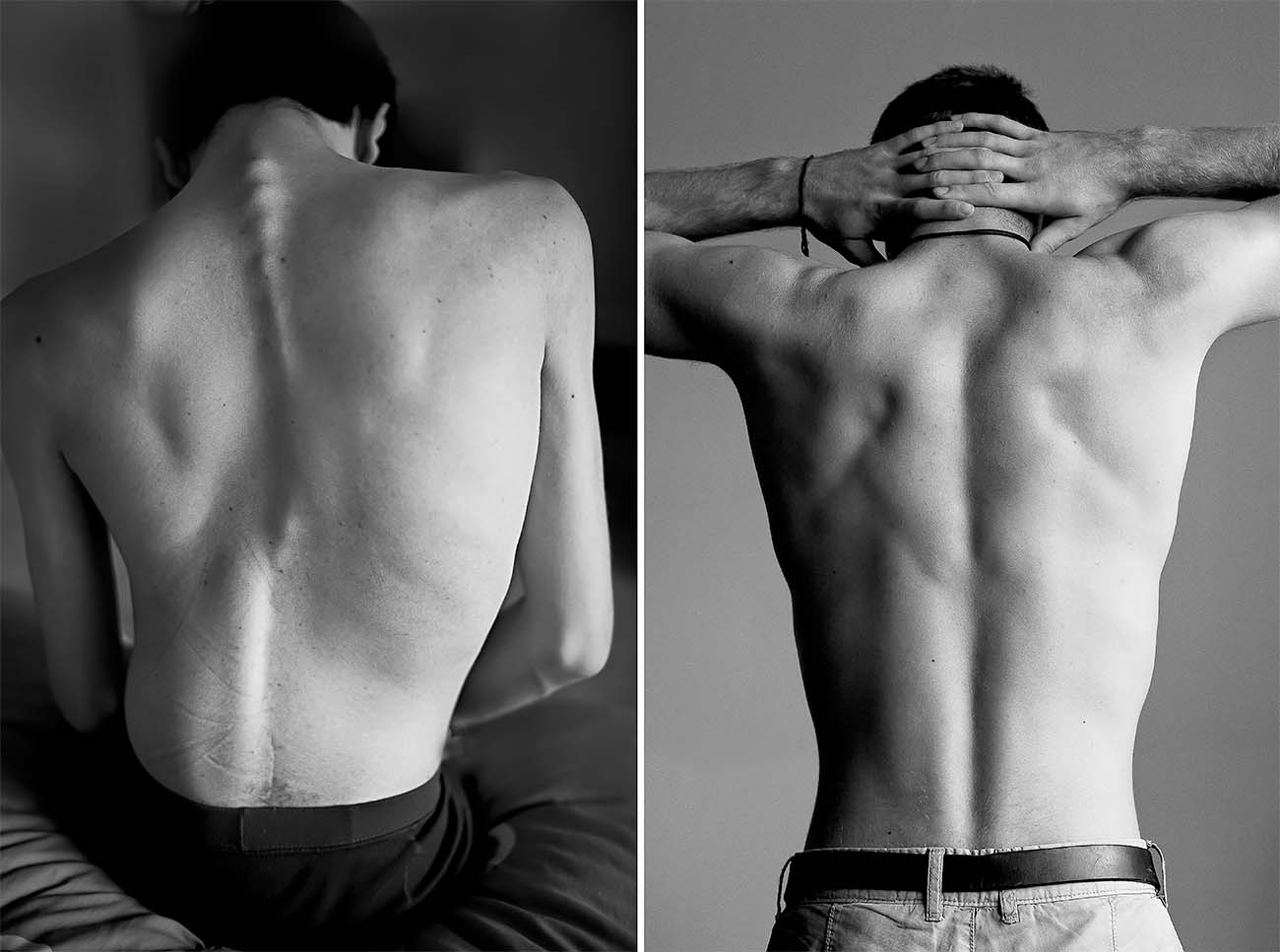

''Twins.'' Photo of sons by Brenda Spielmann. All Rights Reserved.

A cesarean section was performed, which later I was thankful for, because Twin A was born with spina bifida, a neural tube birth defect where the spinal column fails to develop properly, resulting in permanent damage to the central nervous system, causing physical and mental issues.

After Twin A was delivered, I heard commotion among the staff. One of the neonatologists brought him to me and said, "Twin A was born with Myelomeningocele." Smiling, I thanked him, not knowing what that was.

They told me they needed to transport Twin A to Miami Children's Hospital and whisked him away in an incubator. He was beautiful. I held his hand and told him that I loved him.

The doctors told the father and me about spina bifida and warned us of the grim prospects, "He will have no mobility, no bowel and bladder control, might have mental delays...in other words he may live like a vegetable." Once back in my room with Twin B, a nurse said, "You have to be strong for your husband, he is distraught."

I felt overwhelmed by the vague information given to us by the medical team, but I had no time to ponder. While I was breastfeeding the twins, I learned more details about my son's medical condition. He would require an ongoing team of specialists. We were in the low- income bracket and qualified for United States Medicaid. How else could we have afforded healthcare?

A few years later, I found myself on my own bringing up three children, navigating the medical and educational system, and negotiating accessibility and inclusion. I spent much of my son's first years at medical facilities for all the required surgeries and therapies.

I found a sense of peace, whether it was from sheer exhaustion or divine intervention I don't know, but I felt the deepest love and strength and believed everything would work out for my son.

What I hadn't realized was how society still stigmatizes people with disabilities. How do people define "different" and how do those assumptions foment poor self-image and isolation of the "other"? Photography is my language and through it I want to increase awareness of disability. I am hopeful there is an alternative view to society's concept of "normalcy." This is not about acceptance, for there is nothing to accept, only to become what we already are!

Human connection and a sense of belonging is what ultimately matters.

By Brenda Spielmann | Photo by Brenda Spielmann. All Rights Reserved.

www.brendaspielmann.com

Remote Area Medical Clinic, Leburn, Kentucky, 2009. United States Healthcare Refugees. Photo by Dermot Tatlow. All Rights Reserved.

Staffed by volunteers, RAM was founded to provide medical services to the most vulnerable people in the developing world. That was, until RAM realized that the most vulnerable also lived in the United States of America, where RAM now provides more than half of its services. RAM's field hospital setup was originally designed to cater to mass casualties caused by natural disasters in other countries. That was, until they realized that in the United States millions of uninsured and underinsured people are consistently and systemically denied healthcare.

Many uninsured people are workers who hold two—and sometimes three—jobs. Unfortunately, these minimum wage and part-time jobs allow employers to legally avoid providing their employees with medical insurance.

For me, a European photographer who has covered refugees and evacuees from conflicts and natural disasters around the world, I was astonished to see hundreds of American families, with young children in their cars, lined up overnight in freezing conditions to seek the most basic healthcare.

The poem on the Statue of Liberty reads, "Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses..." And here, they were huddled still, on a frozen mountain in Leburn, Kentucky.

People are made to take a number in order to access healthcare at the RAM temporary field clinic in Leburn, Kentucky. As relieved as these families are to access medical care on this day, their abiding question is, "What will we do when we need healthcare tomorrow?" These people have become healthcare refugees in their own country.

By Dermot Tatlow | Photo by Dermot Tatlow. All Rights Reserved.

www.dermottatlow.com

Emerging. Photo by Ana Simonovska. All Rights Reserved.

This vulnerable and exposed fetal position conveys freedom from all social labels, assumptions, conditionings, and false identities people impose on others. The downward motion into the deep symbolizes surrendering to our true nature.

We are born from water. We are propelled by water.

For me, the body and spirit are two faces of the same coin. Both are interconnected and should be nurtured and taken care of equally.

As a yoga practitioner for several years now, I've come to understand the importance of the body as one of the entry points for us to begin a deeper dialogue with ourselves. How we treat the body in many ways reflects how we treat ourselves on a deeper level. I strive for strength, flexibility, and openness for exploration on the physical, mental, and spiritual level. To the best of my knowledge, I am healthy now. For me, health is balance, when all parts of the whole are working together in harmony. Those who are lucky live a long journey physically, inwardly, and psychologically.

By Ana Simonovska | Photo by Ana Simonovska. All Rights Reserved.

www.anasimonovska.online/photography

Sophia Ybarra, 7. Photo by Alyssa Schukar. All Rights Reserved.

As a single mother who runs her own business cleaning houses, Ives has never had access to healthcare or health insurance outside of Medicaid.

Ives advocates fiercely for Sophia and her two brothers to ensure they receive the healthcare and medical attention they need.

"I have noticed they look at you a little differently when you're on Medicaid," she said. "If you have regular private health insurance, people tend to treat you a little better."

By Alyssa Schukar | Photo by Alyssa Schukar. All Rights Reserved.

www.alyssaschukar.com

Across the bridge, the Apple store, the brilliant architectural gem and a retail incarnation of a company with a trillion-dollar market cap greater than the GDP of most nations, including Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Sweden. In the presence of such powerful symbols of wealth and financial success, it seems the only appropriate response is awe. Yet steps away, under this "Magnificent Mile," countless homeless Americans, young and old, of every color and background, able-bodied and afflicted, struggle to survive.

Increasingly, families and individuals struggling to pay medical bills as a result of a serious illness or disability find themselves in a downward spiral into homelessness, beginning with a lost job that leads to eventual eviction.

More and more of our monthly family budget goes to out-of-pocket healthcare even though we have "good" health insurance, and the thought of a major illness or injury depleting our resources haunts me.

Why haven't we had the will to put affordable, quality healthcare at the top of our political agenda?

Our raucous and divisive political climate is forcing us to decide what kind of a nation we want to be and question what makes us "great." At the moment, we seem to be distracted by shiny objects. As we debate what America can and should be, will we continue to regard opulence and excess as the measure of our success, or will we lower our gaze to meet the eyes those less fortunate, who offer us a more profound opportunity to achieve greatness by addressing the needs of our most vulnerable?

By Michael Zajakowski | Photo by Michael Zajakowski. All Rights Reserved.

www.zajakowski.com

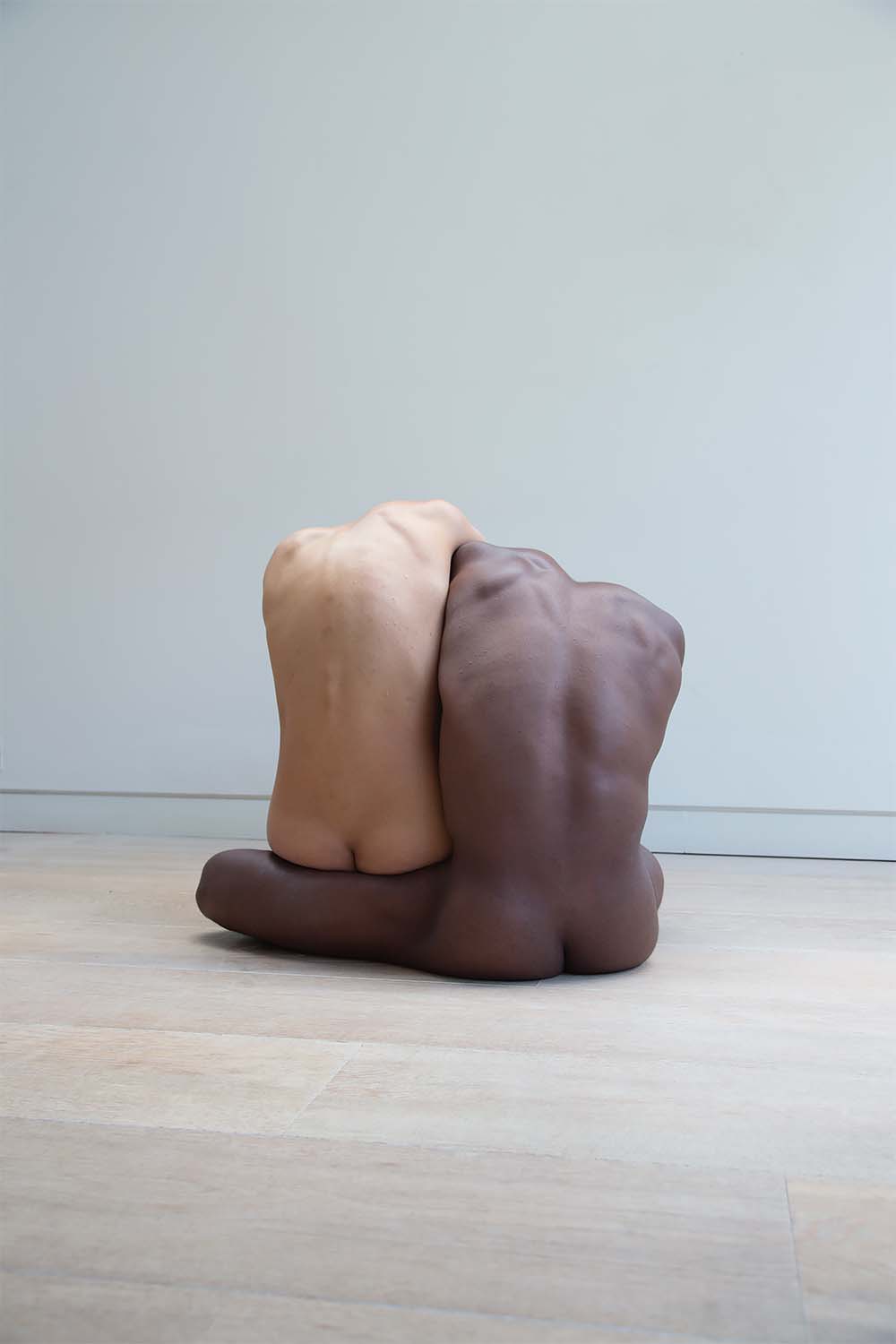

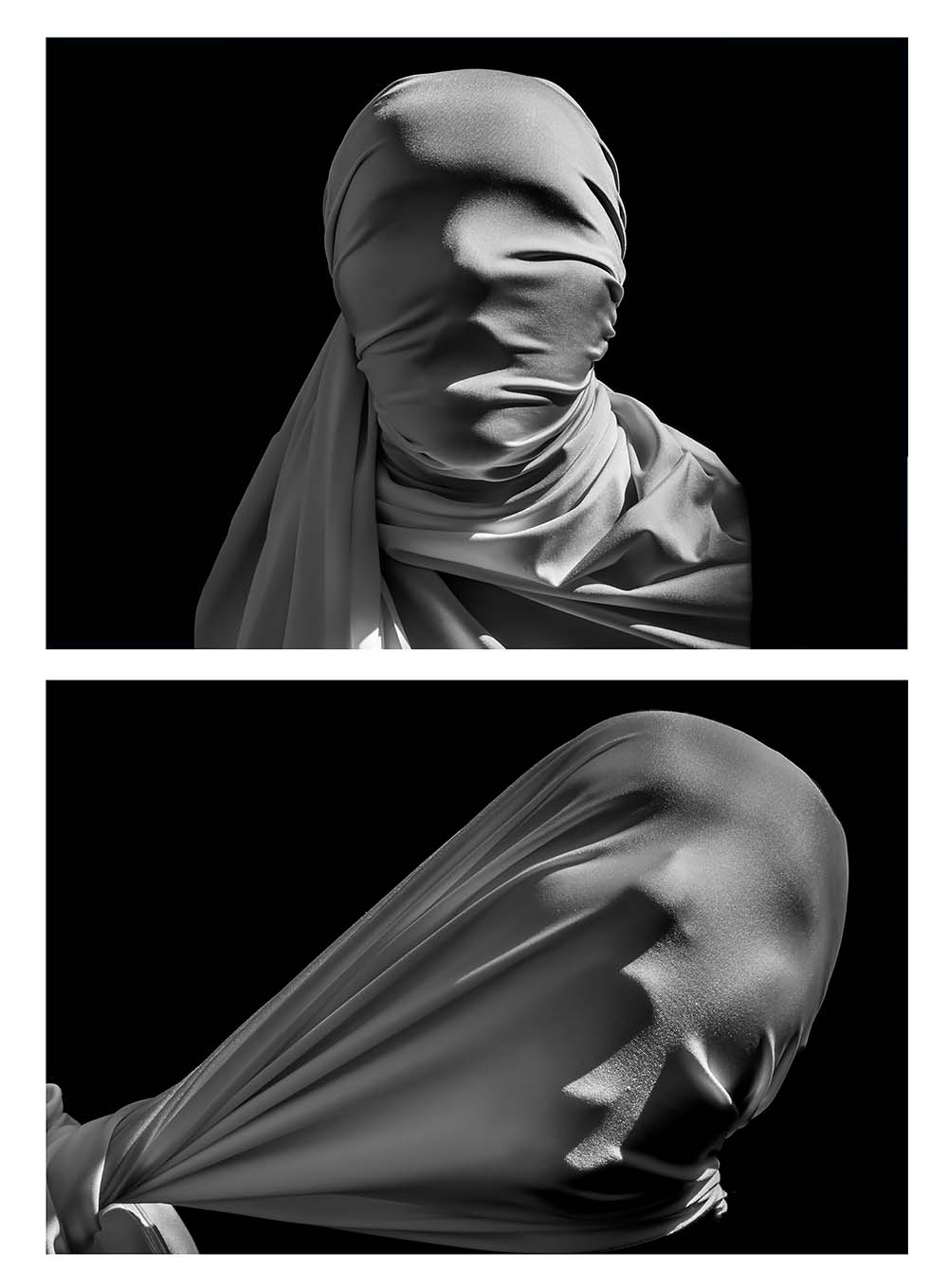

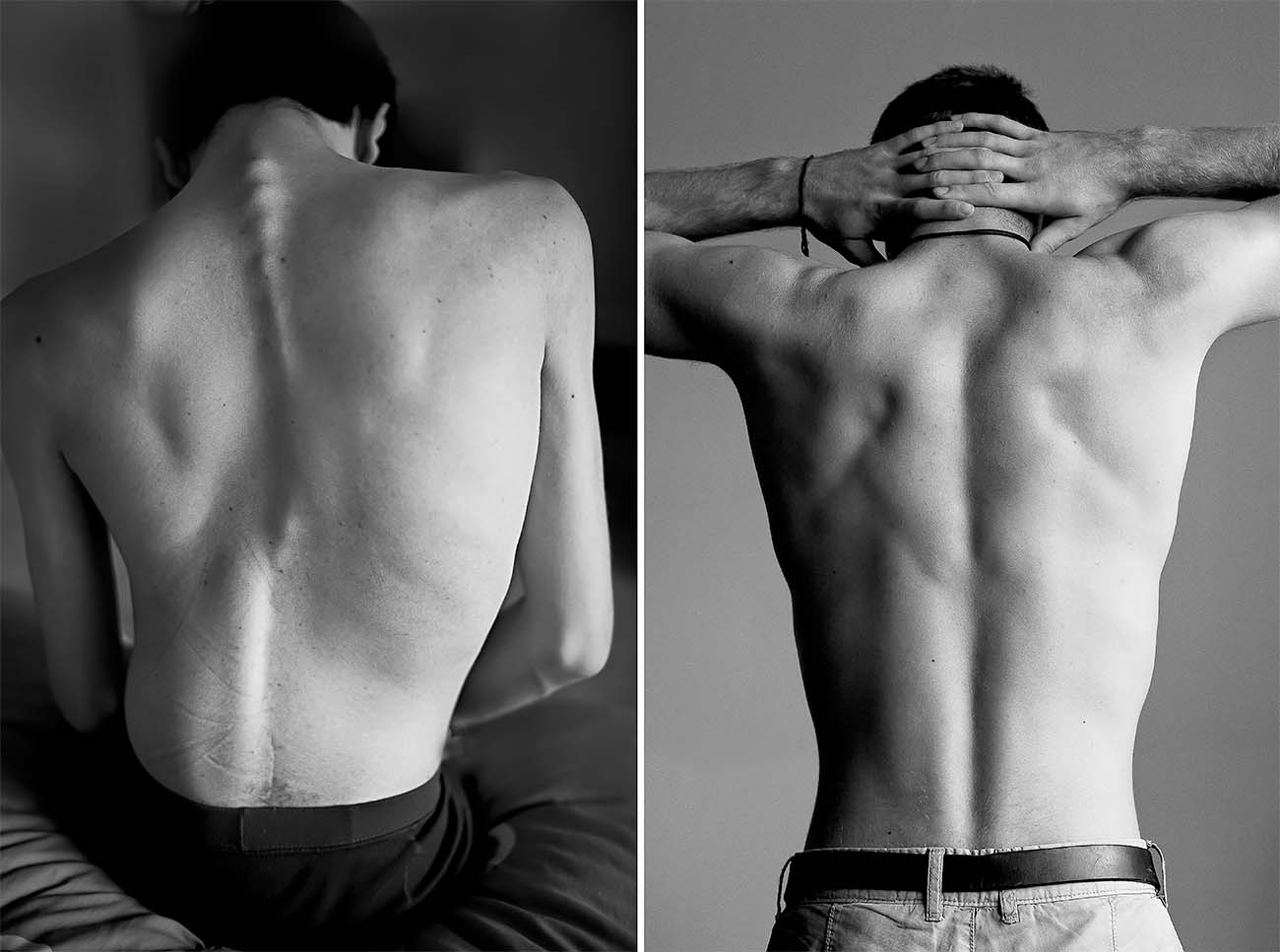

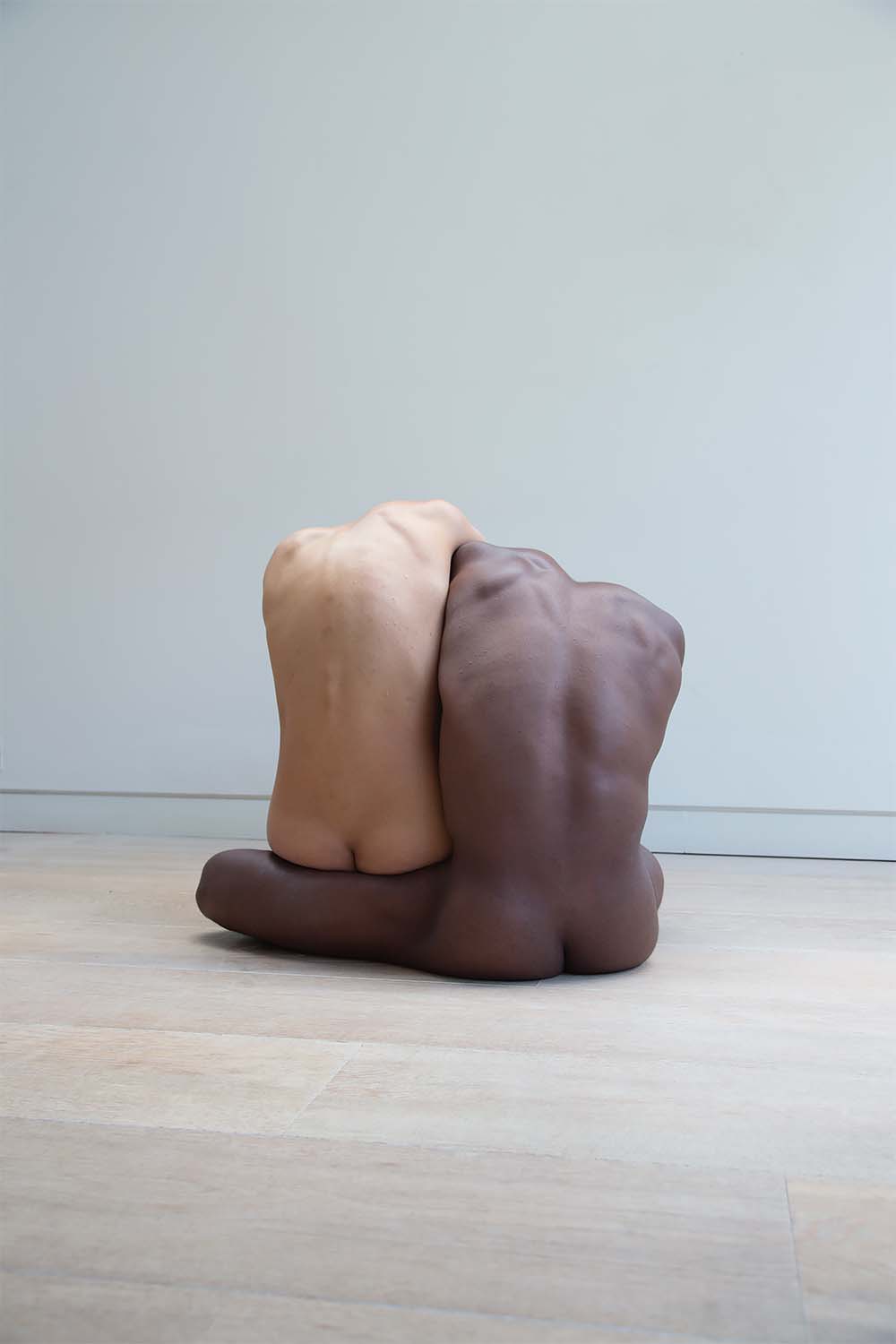

There is an element of alienation present throughout my work, Form and Function. It is in response to the fraught and complicated relationship we have with the body.

There is a disconnect between the imagery and information we are surrounded by on a day-to-day basis and the reality of owning a body. It is also a very personal relationship that changes and evolves over our lifetimes.

I delve into the disconnect we have with the human figure through contorted poses and compositions of figures who are free from identifying features. Without the head, hands, and hair, we do not look at these forms in the usual way, making assumptions and judgments about the individual. Instead, we are free to see them as sculpture and derive conclusions that we otherwise might not see.

Although the forms can be very "inhuman," there is also a delicate sense of humanity about them. The poses, often fetal-like, capture a vulnerability and fragility.

A particular focus for me is the experience of that point at which our body misbehaves, declines, or sounds alarms-when it stops working in the way that we are used to or expect. To be betrayed by your own body like this is a frightening and alienating experience. It's also something that we all go through to some degree, whether it is breaking a limb, developing a chronic disease, or simply losing flexibility with age.

Above all, the strangest and most life-altering experience is witnessing the body ceasing to work entirely.

I witnessed, firsthand, someone going through the long, slow experience of losing control of their body, and because of that process, their connection to the outside world. Undoubtedly, that experience drastically altered my personal relationship with the human form.

A key aspect of this work is the interaction between the figures. They display their humanity through their touch. There is tenderness and trust in the way they hold and curl around each other. In some poses, they lean on each other, balancing and supporting one another. They hold positions that are only possible because of the other figure. They must work together to reach a state of equilibrium.

The images I photograph are shot in homes. Stripped bare, the spaces do not give away too much information about the owner, but instead, act as a reflection of the owner's mental state. Marks on the walls and floors point to situations and actions that have taken place in that space. They are proof that the space is lived in, just as scars and marks on the figure's skin are a record and story of the body being alive.

To me, the body is a delicate and universally vulnerable housing with which we interact with the world around us.

By Chloe Rosser | Photo by Chloe Rosser. All Rights Reserved.

chloerosser.com

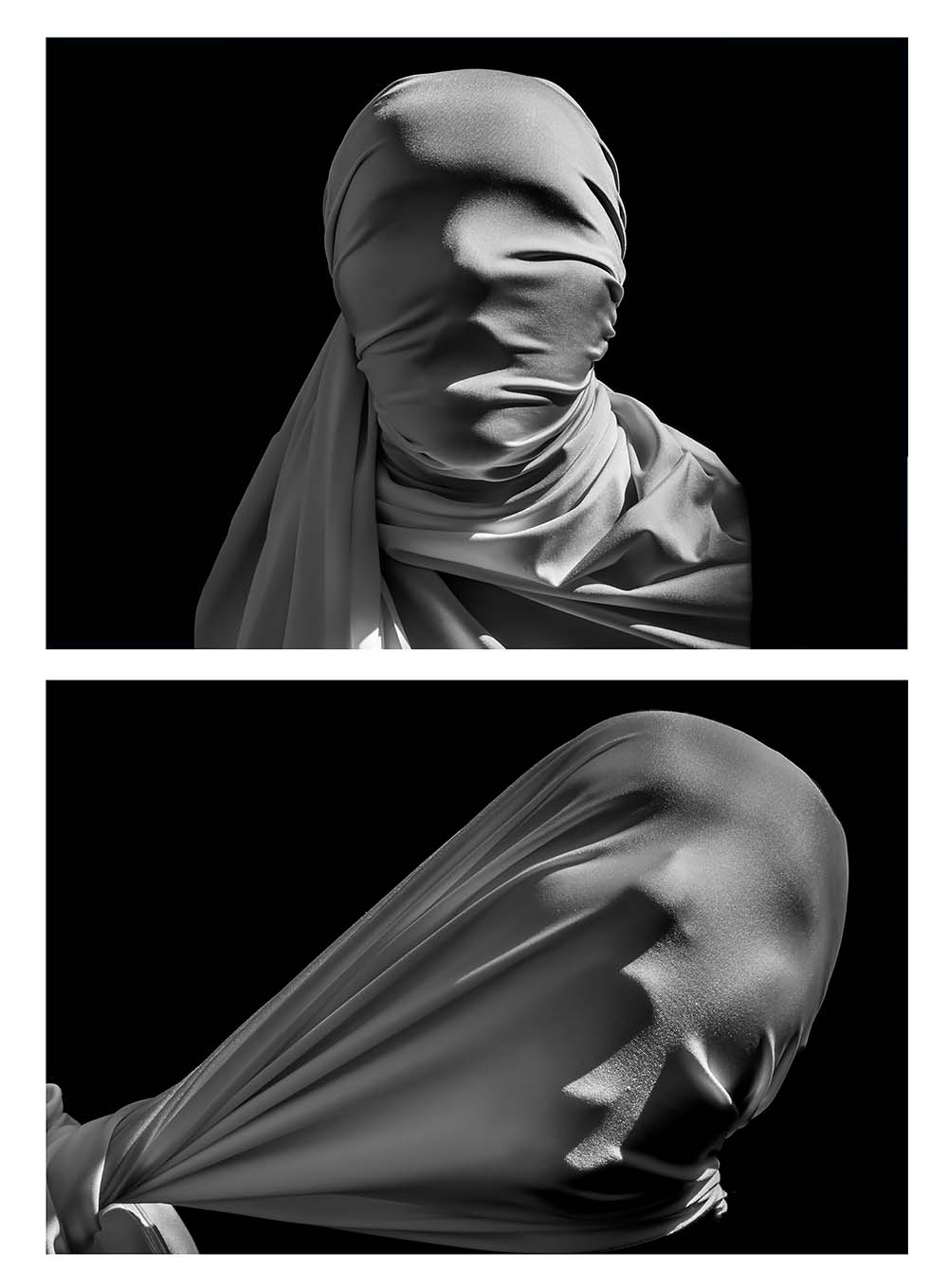

Boundaries. Sister, April 2018. Photo by Evie Scarborough. All Rights Reserved.

My sister expressed to me that it felt as if she should be hidden because of her depression. She felt as if she were a burden. My family members made the best attempt to conceal and keep private the fact that this struggle was going on in our home. Family silence can become very loud.

I managed my emotional response to her illness with photography. I set out to explore the emotional and physical boundaries people face through times like this. I think my sister enjoyed taking part in these photos and the shoot enabled us to become closer.

Spending more time with her is something I have tried to consciously do as a sister. I encouraged her to be productive, otherwise she could easily spend all day in bed or playing video games, growing bored or restless from ruminating, which, like a vortex, led to more self-harm.

Hiding and concealing illness can make people feel ashamed to ask for help and ashamed to seek help for a family member.

The white cloth represents the ways in which society tears and constrains people who are suffering with invisible illnesses.

Upon reflection, looking back at these images, I feel sympathy and compassion, not only for my sister, but for everyone who has been through a tough illness or period like the one I survived with my sister. The experience with my sister has made me extremely mindful of what it requires to maintain her health and the health of my family-especially during stressful times in our lives.

Mental illness is isolating. The tension and strife in my images reflect the suffocating boundaries of mental health issues, but also raise the importance of well-being, acceptance, and a sense of belonging.

Feeling like an outsider, a burden or a problem can have detrimental effects on health in general. This can prove difficult to overcome, living in a world where mental health is often overlooked due to a lack of understanding. Despite the fact that mental illness is a modern world epidemic, there remain extreme waiting lists for support and care. There are many barriers to care because of stigma and because of bureaucratic blockades. And care and counseling can also be cost-prohibitive.

A healthy mind is the key to a healthy body. As a society, we need to realize this and understand that we should take care of our own, and each other's, minds to maintain not only the health of the individual body, but also the body of society at large.

By Evie Scarborough | Photo by Evie Scarborough. All Rights Reserved.

www.eviescarborough.co.uk

FROM THE CURATOR

We are all living organisms, universally fragile and vulnerable.

Everybody, and every body, is interconnected.

It takes only a split second for a life to be disrupted and altered in perpetuity by illness, injury, disease, disability, or death.

Despite modern methodologies aspiring to predict health conditions, health status, and health outcomes, none are absolute. Artificial Intelligence, data analysis, social demographics, algorithms, policy analysts, behavioral scientists, quants, and physicians cannot predict health.

Health and healthcare—the very cornerstones of economic dignity—are essential to unharnessing human potential to its fullest. This multidisciplinary exhibition examines the ethics, people, processes, and systems that constitute the maintenance of, and barriers to, health for human beings.

What does economic dignity mean? It means self-worth, clean housing, access to economic capital, education, a healthy environment, strong supportive social networks, safe public spaces, and positive social structures.

The photographs, art, and essays in this exhibition reveal what it is to be fully human—birth, adolescence, parenthood, family, compassion, athleticism, friendship, conflict, strife, mental illness, harm, survival, illness, injury, empathy, intimacy, disability, overcoming physical limitations, End of Life, and love.

As a group of dedicated photographers, artists, essayists, and physicians, we strive through our work every day toward educated, safe, equitable, just and healthful societies internationally.

What we know is access to quality healthcare benefits society.

What we know is prioritizing public health reduces violence and trauma.

What we know is affordable, accessible healthcare strengthens economies worldwide by leveraging human potential to the fullest.

And, we all know that carrying loved ones and strangers alike through life's unexpected trials stabilizes communities globally.

This multiverse project provokes us to ask seminal questions of ourselves and also of our business and government leaders. How can we—every person, every professional, every industry—include comprehensive health as a priority in our bylaws, our business practices, and our policies? How can we ensure health is first and foremost in our daily decision making?

The electorate, business owners, civic leaders, families, patients, healthcare workers, and community organizers are changing their approach to governance and leadership by making comprehensive health, best practice, and compassion a priority worldwide.

A very promising trend is in our midst: The realization—perhaps a global revelation—that we are all undeniably interconnected.

Kimberly J. Soenen

Executive Producer | Creative Director | Curator

"SOME PEOPLE" (Every)Body