At the end of the 20th century, no more than three bears lived throughout the Alps: they were three males, too old to reproduce.

Since the second half of the 19th century, bears have been the victims of a wild hunt aimed at the annihilation of the species from the Alps. Under the Austrian government, bounties were imposed on the head of every bear killed. This legitimation by way of economic incentive gave a strong impetus to bear hunting, transforming breeders into hunters and laying the foundations for the localized extinction of the species: mission almost accomplished.

In the first decades of the 20th century, hunting continued also involving wolves and lynxes: large carnivores of the Alps were conflicting with the presence of human activities and their number was reduced to the limit of extinction (which in the case of the lynx actually occurred).

In 1996 the European project “Life Ursus” was born with the aim of restoring within twenty years a minimum viable population through the reintroduction of ten bears from Slovenia. Three years later, the first bears were released in the upper portion of the Tovel Valley, in those very Brenta Dolomites that housed the last three bears which survived the previous century's carnage.

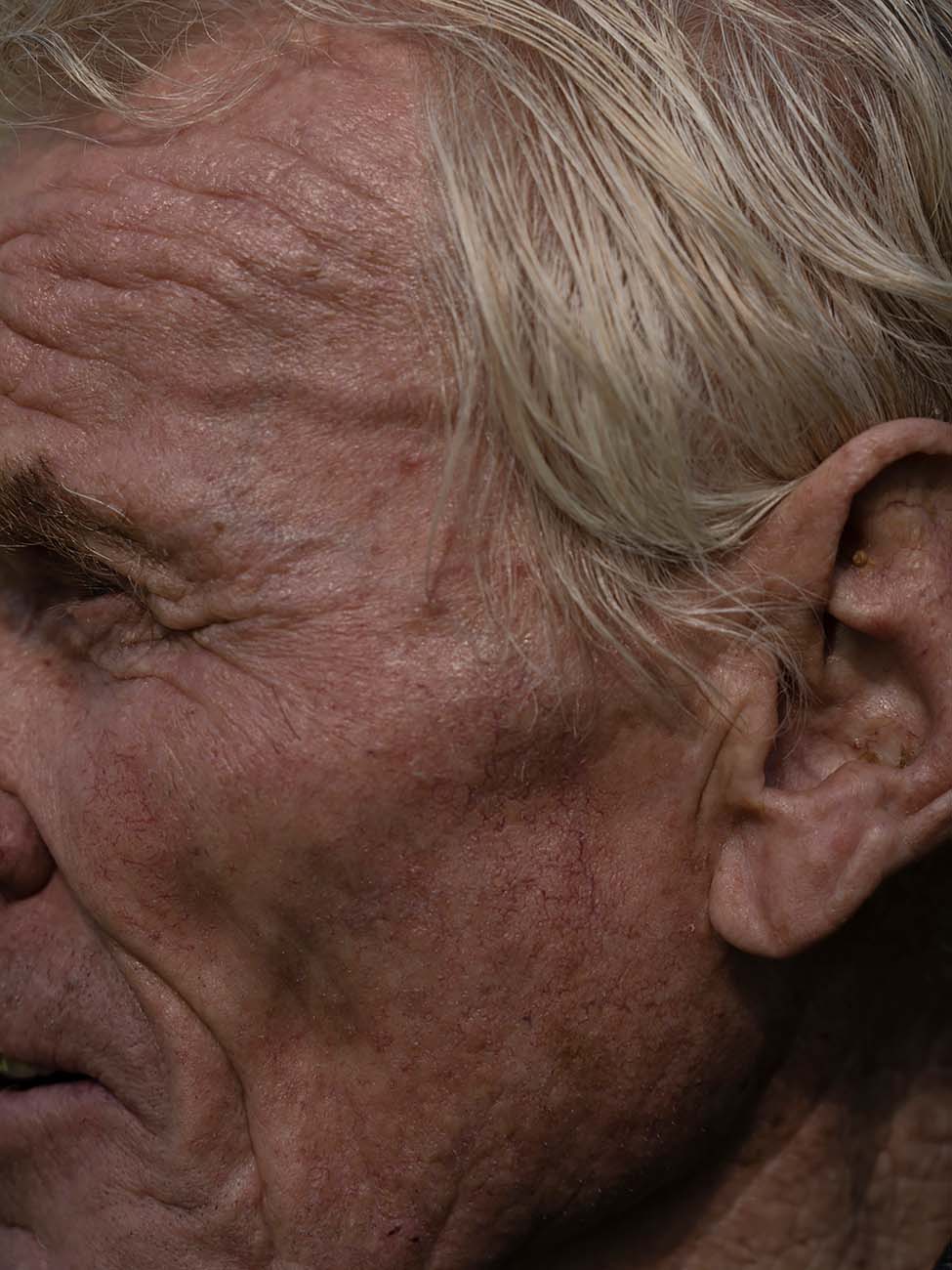

Today in Trentino there are about a hundred bears and their return has reignited the same conflicts that have always marked human-animal coexistence. Their return triggers the ferocity and ignorance of those who, stroking the barrel of the rifle, still argue that bears have never lived here.

Bears' presence, deemed as the achievement of a society able to coexist with nature, has often been used as a marketing factor to advertise the territory and celebrate its biodiversity. The bear has been exploited as a distinctive element, a source of pride for the entire territory. Thus, in the most densely populated mountain region of the world, came the first accidents from close coexistence. Livestock farmers who pay the price of predations and frightened tourists fearing encounters began to voice their concerns. Simultaneously, animal rights movements started mobilizing for the safeguard of bears' freedom. Problems in the management of bears like Daniza and M49 brought the issue to national and international media attention.

Hence, while some see them as a new symbol of a much needed environmental revolution, others see them as thieves or murderers. Some study them, others sneak around their lairs.

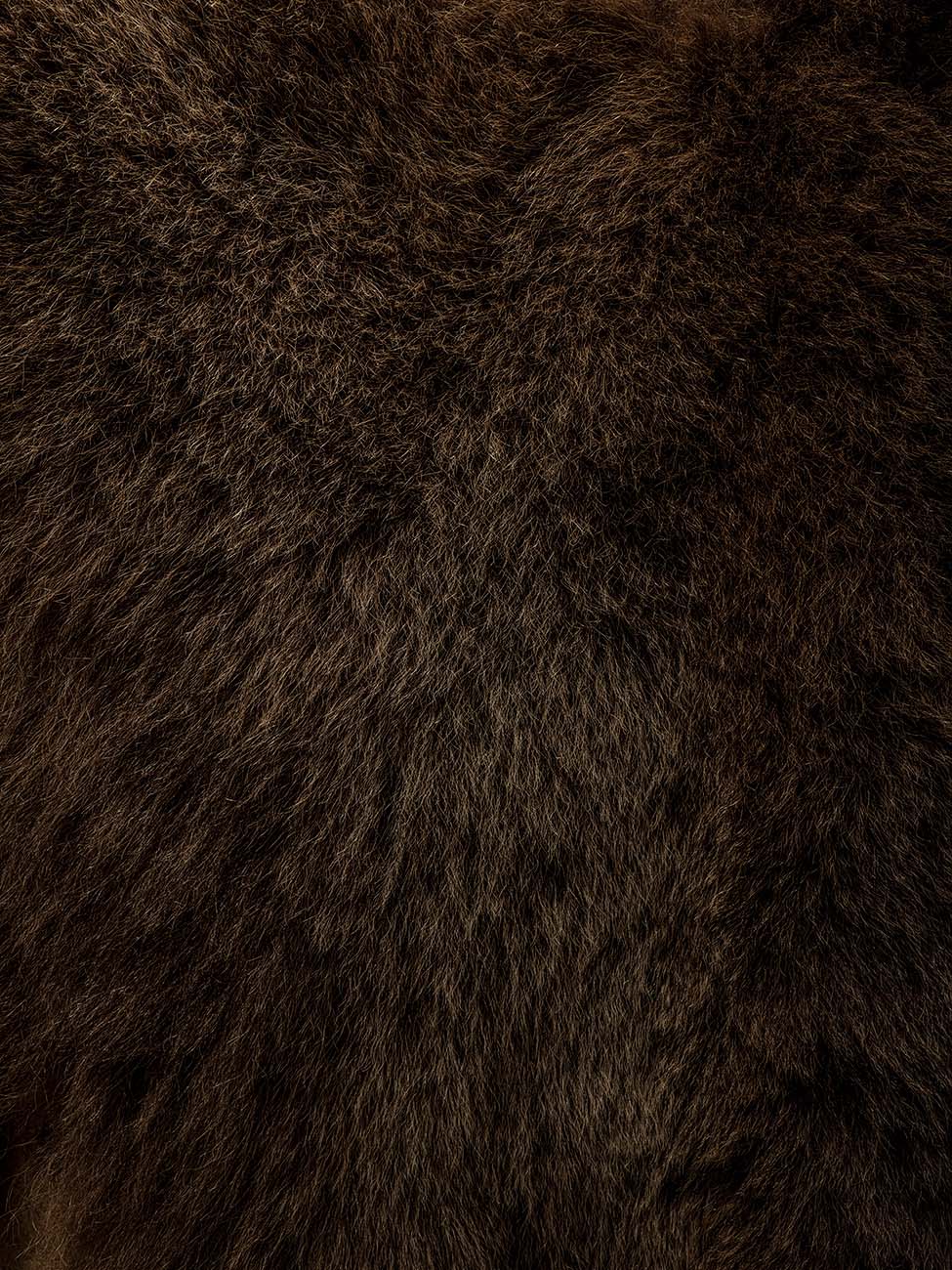

Kirka is the story of the presence of bears in the Alps throughout the centuries: from the countless fossil remains found in Conturines cave, to the myth of San Romedio, from Oetzi the IceMan's hat to the frescoes of Torre dell'Aquila in Trento. Ultimately, Kirka is the story of how to save a species from localized extinction and how to make coexistence, too often threatened, possible.

The project was realized following a proposal from CTRL Magazine.

Luca Rotondo

Following his education in classic subjects and economics, Luca Rotondo devoted himself to photography and in 2013 he launched his career with his first publication "Landscape Assumptions", curated by art critique and photography historian Angela Madesani. Luca Rotondo's research focuses primarily on the investigation of landscape, widely intended as a new idea of human or inner landscape, with special attention to the human aspect and it's spatial relations. He then begins a series of in-depth projects, the theme being portraits of individuals depicted as an architectural presence and the relationship with their surroundings. Each person is therefore in a constant dialogue with his surrounding living space. He continues to work on editorial assignments and has been published in IoDonna, Corriere della Sera, D Repubblica, D-lui, Icon Design, Icon Australia, Domus, Elle Decore, the World of Interiors, Esquire, Interni magazine, Living, Panorama, The Next Building, Planum. Over time he has also collaborated with numerous architects, designers, businesses and media agencies. His "Metropolitan Lullabies" project won him the 12th edition Ponchielli award. Since 2016, he has been teaching landscape photography at IED (European Institute of Design) in Milan. He has participated in several collective exhibitions and some of his artworks are now part of the Bracco Foundation's collection.

Luca Rotondo's Website

@loocaround