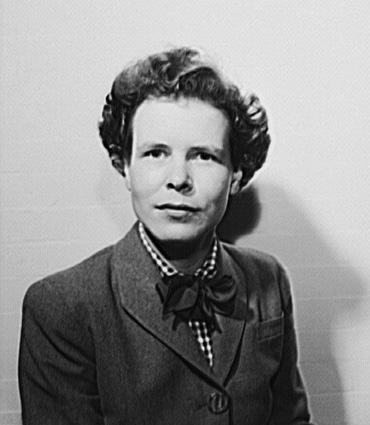

Marjory Collins was an American photojournalist. She is remembered for her coverage of the home front during World War II. She was born March 15, 1912 to Elizabeth Everts Paine and writer Frederick Lewis Collins in New York City, and grew up in nearby Scarsdale, Westchester County. She studied at Sweet Briar College and the University of Munich. In 1935, Collins moved to Greenwich Village, and over the next five years she studied photography informally with

Ralph Steiner and attended

Photo League events. In the 1980s she moved to San Francisco where she obtained an M.A. in American Studies at Antioch College West.

Her work as a documentary photographer was taken up by major agencies. As a result of a contribution for U.S. Camera and Travel about Hoboken, New Jersey, she was invited to work for the

Foreign Service of the

United States Office of War Information. She completed some 50 assignments there with stories about the American way of life and support for the war effort. In line with a new emphasis on multiculturalism, she contributed to photographic coverage of African Americans as well as citizens of Czech, German, Italian and Jewish origin.

In 1944 Collins worked freelance for a construction company in Alaska before traveling to Africa and Europe on government and commercial assignments. Thereafter she worked mainly as an editor and a writer covering civil rights, the Vietnam War, and women's movements. In the 1960s she edited the

American Journal of Public Health. Collins was very active politically; a feminist, she founded the journal

Prime Time (1971–76)

"for the liberation of women in the prime of life." In 1977 Collins became an associate of the

Women's Institute for Freedom of the Press.

Her work is included in the collection of the

Museum of Fine Arts Houston. She died in 1985 at the age of 73.

Source: Wikipedia

By January 1942, Collins had transferred to Washington, DC, to join

Roy Stryker's famous team of documentary photographers. Over the next eighteen months, Collins completed approximately fifty different assignments consisting of three thousand photographs. Her upbeat, harmonious images reflected the OWI editorial requests for visual stories about the ideal American way of life and stories that showed the commitment of ordinary citizens in supporting the war effort.

Documenting the lives of Americans, discovering my own country for the first time, I was freed of the whims of publicity men wanting posed leg art. -- Marjory Collins

During World War II, race and ethnicity consciousness heightened around the globe. United States

President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 on June 25, 1941, to reaffirm a policy of full participation of people of every race, creed, color, and national origin in the national defense program. Multiculturalism became a topic of major importance for government agencies as the United States geared up for war. Collins worked closely with OWI colleagues

John Vachon and

Gordon Parks and contributed to a substantial photographic study of African Americans.

Many of her assignments involved photographing

"hyphenated Americans," including Chinese-, Czech-, German-, Irish-, Italian-, Jewish-, and Turkish-Americans. The photographs were used to illustrate publications dropped behind enemy lines to reassure people in Axis-power countries that the United States was sympathetic to their needs. For example, using the popular

"day-in-the-life" format favored by picture magazines, Collins portrayed the Winn family at work, at play, and at home. The Winns had arrived in New York from the Czech Republic about 1939 and appeared to be thriving in October 1942.

On the job, Collins gave rein to her curiosity about how the other half lived. Roy Stryker wrote in his April 13, 1943

Gossip Sheet for OWI staff,

"Marjory is in Buffalo, working on women in industry. This is a special story on women workers for the London Overseas Office." "These photographs should ... portray representative types actually at work rather than posed 'cuties,'" and should show

"the very important contribution made towards final victory and how they have adapted themselves to wartime conditions." For one of her topics, Collins covered a young widow (possibly giving her a fictitious name) and her six children, all less than twelve years of age.

"Mrs. Grimm's" work outside the home as a crane operator forced heavy responsibility on her older children and required that her younger daughters stay in a foster home Monday through Friday. Some images reveal the family's poverty and their struggle to maintain nutrition and housekeeping ideals. With her social reform interests, Collins felt that this assignment was consistent with Stryker's encouragement to make

"pictures of life as it is." She considered the Grimm Family images among her very best, but they also clashed with the glamorized Rosie-the-Riveter concept called for by the OWI.

Fellow OWI photographer

Alfred Palmer complained that Collins' photographs sometimes showed

"the seamy side of life." Palmer and others believed that the OWI had two roles--straight news for publication in the United States and propaganda for overseas audiences. Palmer's news group wanted to clean up photographs, while Stryker's photographers wanted to show how deeply Americans sacrificed to support the war. The Grimm Family photographs are among the last images by Collins that survive in the FSA/OWI Collection. A set of almost fifty photos taken in Tunisia in May and June 1942 are credited to Collins, but no textual records have been found that explain this trip.

Source: Library of Congress