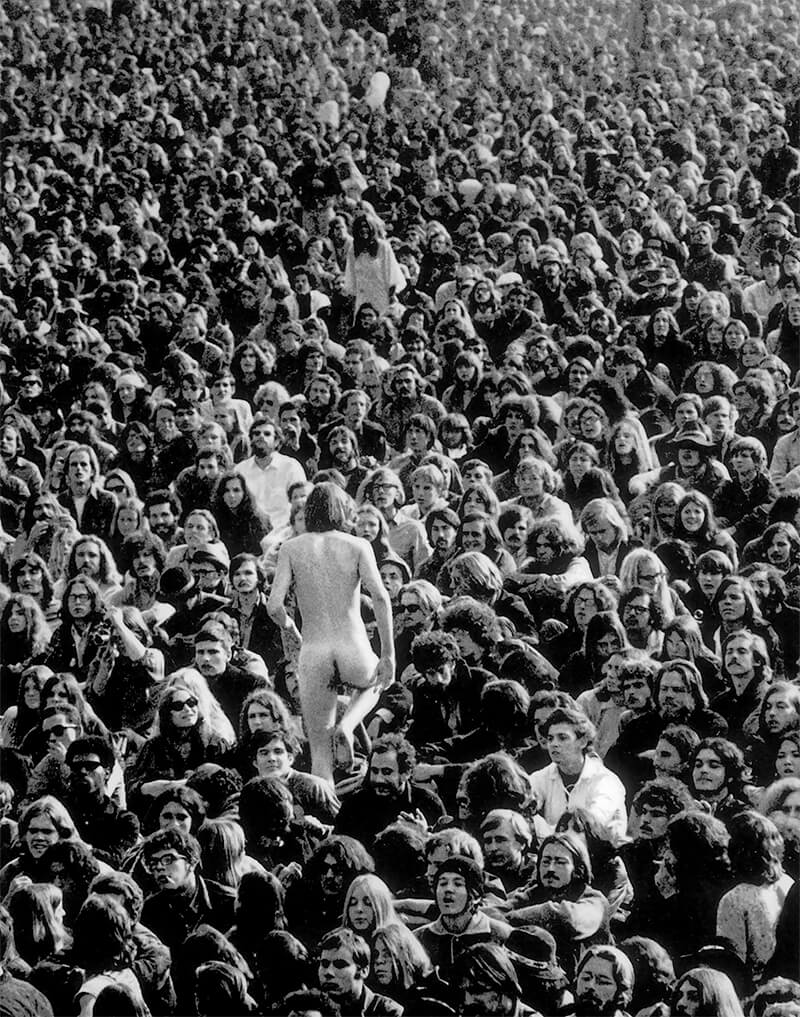

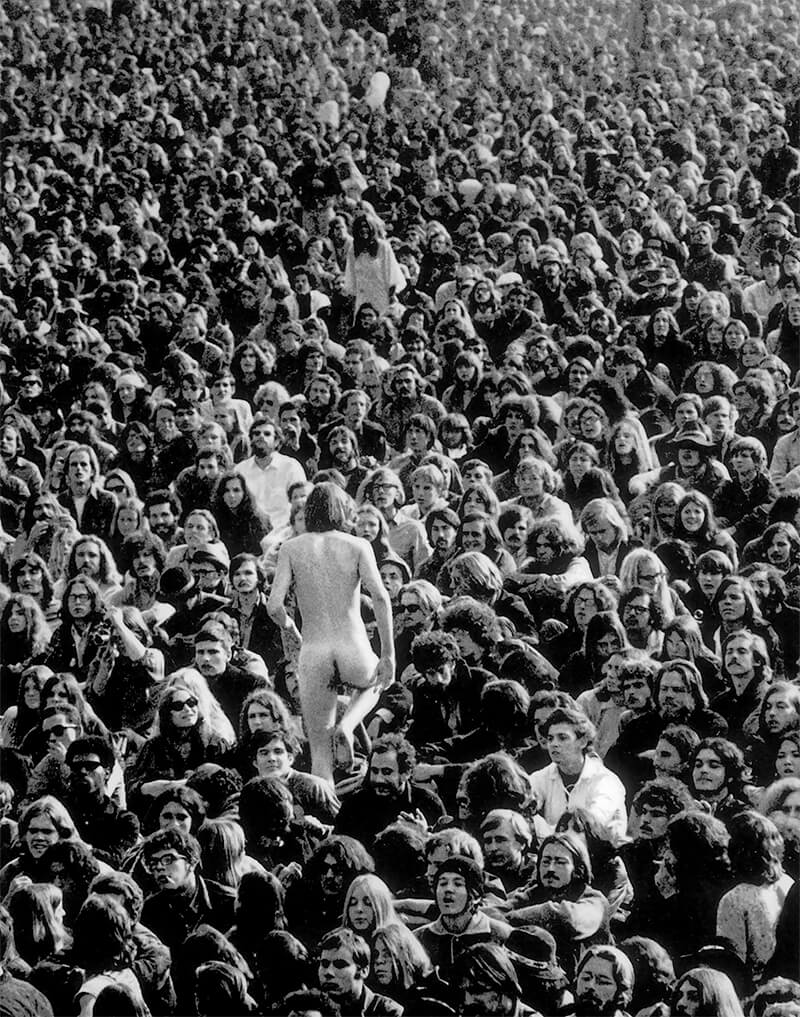

Bill Owens took iconic photos of the Hells Angels beating concertgoers with pool cue sticks at the Rolling Stones' performance during the Altamont Speedway Free Festival four months after Woodstock on December 6, 1969. Altamont, which included violence almost all day and one stabbing death, is considered by historians as the end of the Summer of Love and the overall 1960's youth ethos. This series of photos include panoramas of the massive, unruly crowd, Grace Slick and Carlos Santana on stage with the press of humanity so close in, they're clearly performing under duress.

Of that day, Owens has written: I got a call from a friend, she said the Associated Press wanted to hire me for a day to cover a rock and roll concert. I road my motorcycle to the event. I had two Nikons, three lenses, thirteen rolls of film, a sandwich, and a jar of water.

Hells Angels Beating Man with Pool Sticks © Bill Owens, from ALTAMONT 1969 published by Damini (Milan Italy)

Owens was so fearful of retribution by the Hells Angels that he published the photos under pseudonyms. Some of the negatives were later stolen; Owens believes by the Angels. He continues to have conflicted feelings about Altamont. He had no interest in violence and took no pride in photographing it.

In 1972, Owens released a book of black and white photography called Suburbia, also now an American icon. Irascible, stubborn, funny, grouchy, ornery and deeply rooted in small town life, Owens is built like a middleweight puncher and wears his hair as though he was a Marine. Indeed, Owens was never a hippie, but a clean-cut newspaper photographer, husband and father, who joined the Peace Corps to serve his country and do good. Turning 80 this September, Owens has also had noted careers as a craft beer brewer and pub owner, a magazine publisher many times over, and is now a distiller. His books include Suburbia, Working, Leisure, and many others; he is the recipient of a Guggenheim and two NEAs; his work is collected in leading museums the world over, including the Smithsonian.

Recent coverage of Owens includes an April

retrospective in the New York Times of his Altamont photos for the event's impending 50th anniversary. The photos are available for viewing at

Owens' website.

Hells Angels © Bill Owens, from ALTAMONT 1969

I first met Owens at the defunct Rostel Gallery in remote and far northern Dunsmuir, CA, in late August or early September of 2008 (I remember because my daughter had just been born, and the event was the first outing of her life), where they were showing images from

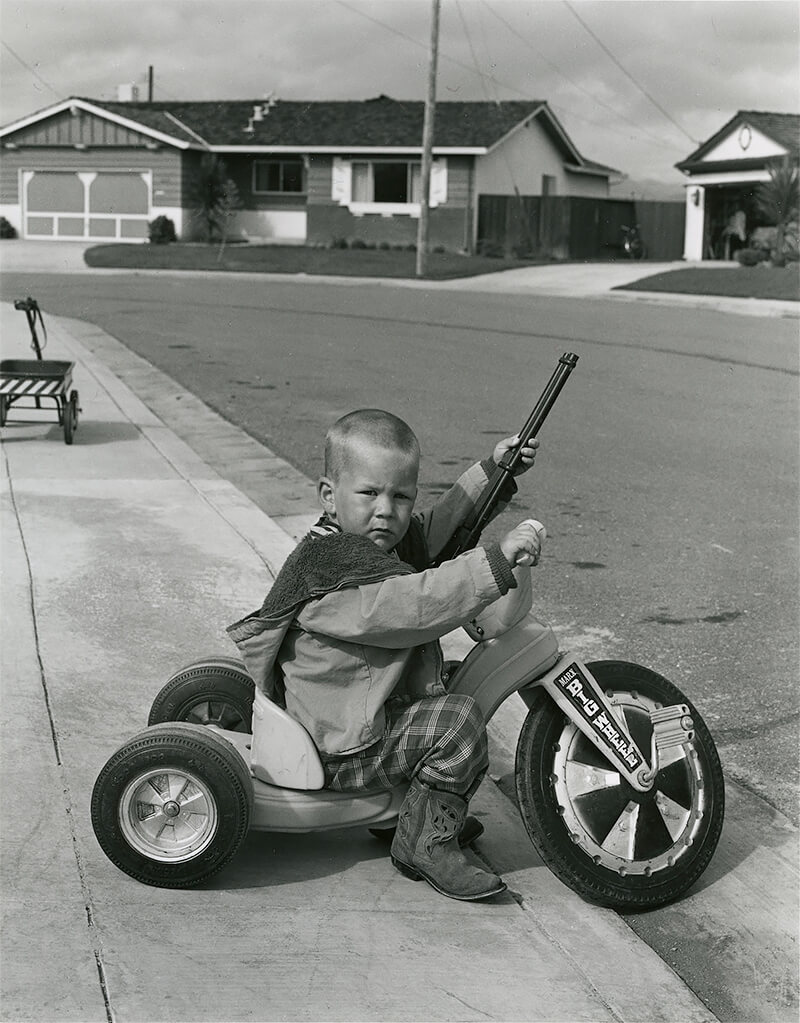

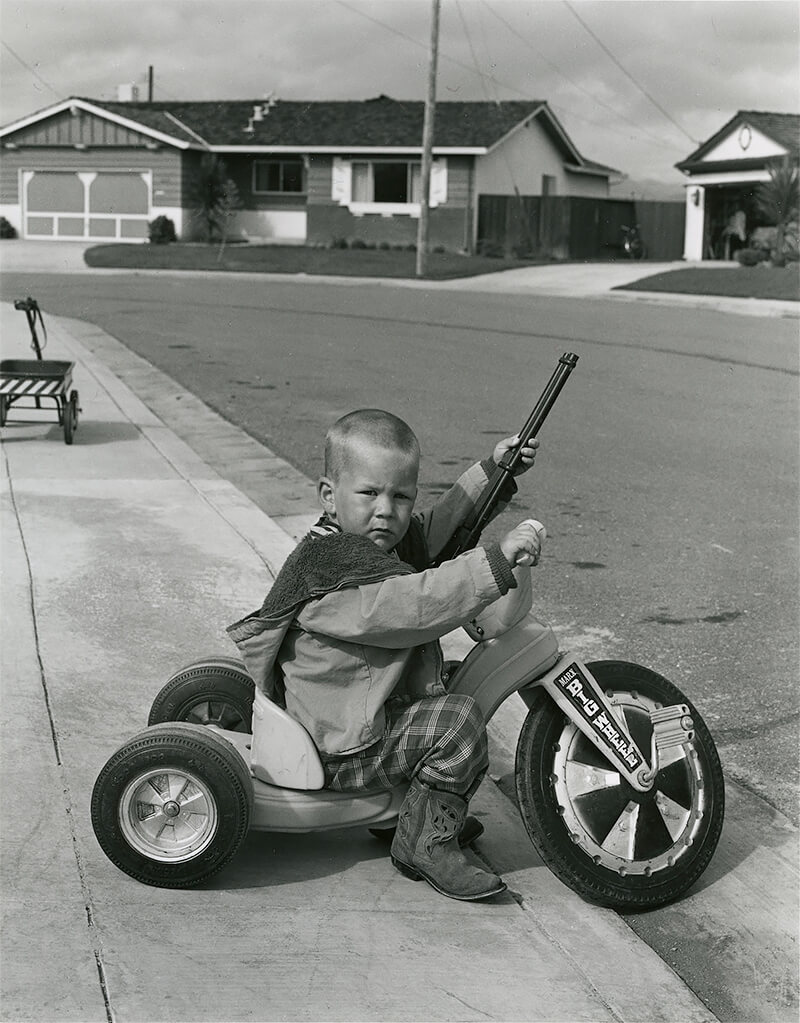

Suburbia. These are images of people embarking on a new, modern way of life that they look excited by, but also confused, as though technology and the modish styles of the time were costumes they were still getting comfortable in. Owens' photograph of a young suburban boy wearing cowboy boots, carrying a toy rifle and riding a Big Wheel, Ritchie, has always haunted me, though I couldn't say precisely why. I have thought of Owens' photograph many times over the past few years in Donald Trump's America. What haunted me about Ritchie in 2008 I now have words to express: a latent violence permeates our society, everywhere, even in the suburbs, no matter how modern we become, no matter what new technology we have. Owens likely does not see Ritchie this way, in fact I know that he doesn't-he keeps in touch with his subjects and has photographed Ritchie as an adult. Regardless, if I was to show one image to explain America to a foreigner, I would show them Owens' Ritchie.

Ritchie, Suburbia © Bill Owens

You know, yesterday my ex-wife, Janet (married 18 years), and I went to an old Peace Corps Volunteer's house and we looked at photos from then. I served with Janet in Jamaica. My current wife, Carol (married 22 years), is in Palermo, Italy right now taking cooking classes. I'll still be the best cook when she gets back. (laughs) Her family is Sicilian, but she's American as apple pie. I see my-ex wife all the time; we have two grown sons, three grandchildren. The Peace Corps called Janet and I in November that year and in February we went to the international school in Vermont to get our teeth fixed, have physicals, see who got along with who. After Vermont, we went to Puerto Rico for a week to get used to a tropical climate. Then we went to Jamaica. I didn't have much of a choice because I have no language ability, my test scores in English were very, very bad. English was the only language I could serve in so they sent me to Jamaica.

What were you supposed to do there?

I have a teaching credential signed by Ronald Reagan to teach high school. We were schoolteachers in Maroon Town, way up in the mountains above Montego Bay. After one year, they moved us to another village near Spanish Town. I loved it. I taught English, general studies, soccer, some community development, got seeds from USAID, and helped people scrounge up lumber to build houses. After our service, we went to Europe and we hitchhiked around Europe.

Do you keep in touch with anyone in Jamaica?

No, I moved on. I couldn't keep in touch. I came back and wanted to be a photographer. I went to San Francisco State at the height of the 'stop the war' movement. Janet got pregnant, and I got my first newspaper job. You can't hang on to those relationships when your life has moved on very quickly.

The Village, Jamaica, Photographs from 1964-1966 made during Bill Owens time in the Peace Corp. © Bill Owens

A Peace Corps photographer came to our village and took pictures of us and the other Volunteers and as soon as I saw what he was doing, I said, 'Oh my god, I want to be a photographer.' So I bought a Leica camera and started taking pictures. I bought it for $10 because it had a pinhole in the curtain, the little fabric curtain that opens to take a photograph. I took shoe polish and plugged up the pinhole and so that camera worked fine. I just figured it out. You got plenty of time when you are in the Peace Corps.

Have you ever been back?

BO: I went back a few years ago and now there's more people. They still have a bad situation. There's no jobs and everybody has nine children. They have got to stop having so many children! Nobody wants to take that issue on because of the church. The world's doomed, you know? Let's have nine children and you can't feed them or educate them and every society does that.

What were your first pictures?

BO: I did a photo essay, there are photos on my website. I spent about six to seven months documenting this little village. I had a show there and just last year we published a book on it and had an exhibit. They're nice photographs and they show the people working and baptisms and a dead man. I tried to show the lifestyle of the village as best I could. That book is called

The Village. I am a documentary photographer. I want to show life. That's what

Suburbia is about. I'm trying to document the culture. I was always interested in sociology and community and things like that. I was raised on a small farm and we had a community center (Citrus Heights, CA, near Sacramento). We knew our neighbors. Do you want to hear a little side story?

The Village, Jamaica, Photographs from 1964-1966 made during Bill Owens time in the Peace Corp. © Bill Owens

When I was about 12 years old I wrote down on a piece of paper-you have to remember that I lived on a farm so every 200 yards was another farm house and everybody had three to five to ten acres, everybody had dogs and cats and horses and cattle-so I wrote down 'For 25 cents I will shoot your cat,' and I turned it over and wrote 'For 25 cents more, I'll bury it.' I went to my mom to borrow the gun and she would not loan it to me. I have a lot of good stories like that. I have a note my mother saved for me-and when your mother passes you are going to get a cardboard box of everything-and in that cardboard box was a note from my dad, 'Dear Son, I bent your knives and forks, I broke your plate and sold your bed. So now you are 21. Call me sometime.' Isn't that wonderful? (laughs) Your dad is saying you're grown up. He didn't sell my bed. He was just joking with me.

I'm not sure how to take those stories. Would you tell me about Altamont?

A book on Altamont is coming out, it's being done by Damiani out of Italy, it's called

Bill Owens: Altamont 1969 (The book was released May 21st). The

New York Times already ran something, and a guy from the

Washington Post flew out here and we walked out there, after 50 years we returned to the scene of Altamont. I have a real homerun on my hands because of Mick Jagger.

Hells Angels © Bill Owens, from ALTAMONT 1969

Yes, when I worked for the newspaper for 14 years. I loved the paper (

Livermore Independent). I love journalism. I was laid off with a reporter because they had to downsize. My wife left because I wouldn't go get a real job working in a factory or something. The

San Francisco Chronicle wouldn't hire me, I was over-qualified. I had

Suburbia out. Nobody would touch me. You can't make a living stringing for Time. I competed against Annie Liebovitz for a job at

Rolling Stone, the difference was I had a wife and two kids and she was free. Who's rich and famous now? Not me. Hang out with Hunter S. Thompson? I'm not going to hang out with any crazies like that. I maintain that he and Irving Penn glamorized the Angels. That made them rich and famous. I had to hide from the Angels! I wrote to the CIA or FBI back then to see if I was on that list [because of his photographs of anti-Vietnam protests]. It turned out I wasn't but I was down there everyday. I went to college during the day and drove a cab at night and we did what we could to stop the war. I photographed a lot of violence in those days. When the Altamont pictures came out, I didn't dare put my name on them, so I used an alias and they sold all over the world,

Esquire, Rolling Stone. I would not publish who I was because the Hells Angels would come and murder me.

You have said that you don't take pride in the Altamont photographs?

I found it ironic that a person who believes in doing good was making money photographing violence. I was doing it for the newspaper and the Associated Press. I put those files away and then the negatives got stolen and 50 years go by and there's a lot of interest in the end of the Summer of Love. That idealism with the Kennedy assassination and other assassinations, Woodstock, and then Altamont came along and people were being beaten and killed and that dream was over, folks. I had a baby at home. I'd tell people, 'I don't go to rock and roll concerts and smoke dope and hang out with people like that. I have a wife and a kid.' I wasn't going to go smoke dope all day, no way. I never got into that culture. I was a responsible young man. I had been in the Peace Corps, I believed in the country and I wanted to do right. You don't hear that from many people.

And now you're running the American Distilling Institute?

I have eight employees, my payroll is $50,000 a month right now. Workshops, books, take a look at the website:

Distilling.com. I had opened Buffalo Bills' (the first craft brew pub in America) a couple of years after I got laid off from the paper. Then I sold that because that's 18 hours a day seven days a week. I had an antique store like the American Pickers, you ever watch that show? I would never pay $40 for that shit. That only happens because they're on TV. They have an antiques store in Nashville and next door to them is a distillery. The guy there tells me, 'Bill, every two hours a bus shows up and they pile into that store and they buy everything in sight and that evening a truck shows up and restocks the store.' They're probably doing a million dollars a year. My store was in downtown Hayward and after six months I closed it because people are crazy. That stuff has no value except romance. I inherited some money after my mother passed and I wanted to see America so I loaded up everything into a cardboard box and drove around America for three months. I got back and was having coffee with your typical kid with longhair and he said, 'I'm going to start flipping property,' and I thought 'You ought to go look in a mirror. You don't look like a banker to me.' I got in my car and drove to the county seat and did my [Doing Business As] for American Distilling Institute, and opened a bank account with $100 and within three months I did a trade show and 86 people showed up and now 15 years later 2000 people show up. I grew a business out of nothing. That's what counts. All there is in life is luck, that's what I feel. My sons are 50 and 45. Andrew and Eric. Eric now works for me. Andrew is a high tech guy. Both have degrees in biochemistry. They took after their mother, not after their dad. They knew better than to go into the arts. (laughs)

Do you still take pictures?

Of course! I take pictures all the time. I took really great pictures at Altamont last week. Yesterday, I went to a gallery opening with Janet and took some pretty cool pictures of 50-year-old women painting landscapes. It's fun, I like to slum it with real people. (laughs)

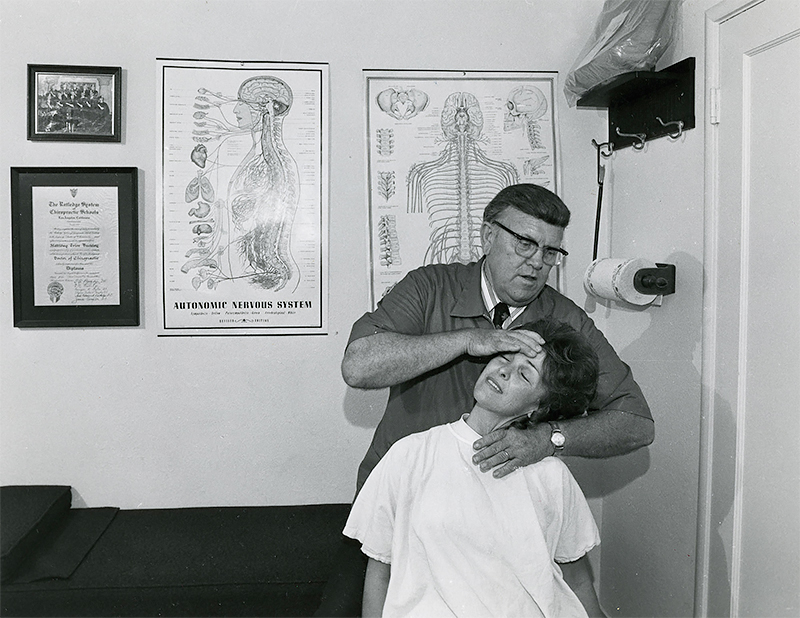

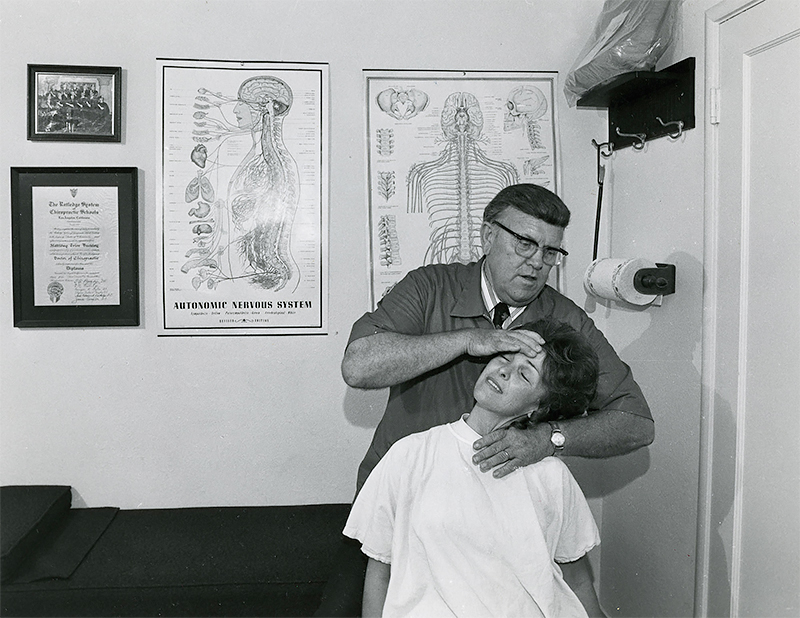

Working, 1976 © Bill Owens

I don't know any artists. Why would I associate with photographers? They don't exist anymore. I don't know anybody in the business. I know some people in New York who have shows and publish but they don't come here (Hayward, CA). If you come to my house on the fourth of July, it's local people and people I have know for a long time. That's how it has always been with me.

You never had to teach like so many of us do?

I did not want to teach. I wanted to be a working photographer. My legacy will be ensured at some university someplace. We're talking to a number of them from Yale to a place in Austin, Texas (Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin) and Stanford where the archives will go eventually. I have a woman working on my archives full-time. I know the people at the Getty quite well. But there's no money there. I have a home office, I go to the Post Office every morning, my world is around distilling. I'm planning a trip in fall, going to Newfoundland, then Ireland to visit craft distilleries; none of the big distillers are in my world. I am about the mom and pop distillers. Lots of farmers are on my mailing list who have a distillery going with their own ingredients, from pears to barley to wheat to sorghum. The small people, the real people.

What if you had to choose one photo as your legacy?

One? That's too hard to answer. The one that probably symbolizes America the best is Richie on the Big Wheel. I went back 30 years later and photographed him on his Harley Davidson that he only brings out when the sun is shining because it's worth about $40k. When I do my slide show, I do the before and after.

To me, Richie suggests that Trump's America was always with us, waiting to come out again.

That picture is full of symbolism, the cowboy boots, the scowl on his face. The story behind the story is that today when you visit Richie, he works for Stanley Garage Door Company, he installs garage doors, lives in suburbia with a wife and a kid. He's not an evil person. His daddy didn't give him millions of dollars. I am always interested in the story behind the story about what America is about. Not the superficial images of America.

Tell me about Buffalo Bills.

I opened the first brewpub in America, Buffalo Bills Brewing. I was a home brewer. I was broke, my wife had left, and I belonged to a home brew club and somebody said, 'California law's going to change you can sell your beer regardless of the source.' So I went to Davis (University of California at Davis) and met the college professor who went to the state legislature and changed the law. I had a four month lead time before the laws changed and I went to the guy who did my taxes and I said, 'How do you get money? I don't know how to get money,' and he opened up the desk drawer and pulled out a limited liability partnership agreement. He said, 'White out 'almond farm' and put in 'brewery'.' I raised $92k and built Buffalo Bills. It lasted for 14 years, long enough to get my kids through college. I wish I could have opened a bottling line. I knew the Sam Adams guys, I knew all those guys. They all started with me. I published American Brewer Magazine for 12 years. Published Beer magazine and I published American Distiller. The Smithsonian called me up and wanted some of my schwag from Buffalo Bills. I was thrilled to death to give them coat pins. A graduate student came to see me a couple years ago and he came back two years later and said, 'I finished my thesis and here's all your stuff back.' I asked if I could convert the thesis into a book, so I did and it got out and the Smithsonian called me and said, 'We'd like to collect your drawings on page 56 and some other stuff.' I'm collected in the Smithsonian in photography, brewing, and I hope one day in distilling. Not many people can put that under their belt.

What would be your last beer or distilled drink on earth?

I'd probably drink beer, something from Dogfish. There's a beer called Prankster from Northern California. It's one of the greatest beers in the world. Part of the fun in my life is to go down to my local pub on Thursdays to hang out and bs the local guys, and to go to the bookstore. I live local. I live a mile from the PO and they see me every morning between 10 and 11 picking up the mail. I do $11k a year in mail.

What do you ultimately think of your Peace Corps service?

BO: Janet and I were discussing that yesterday. We don't know if we helped out other people but it sure was a life-changing thing for us. I could have been there with John McCain, bombing women and children. My life went the other direction. I went into the Peace Corps to be a schoolteacher and help people. I think that's really good, to give back, and most people don't think about that. You want to leave a legacy, that you left a good mark on the earth. It's all 'Me, me, me,' and, 'Money, money, money,' and having the nicest furniture in the world. You'd love my place, I have a little cottage, it's funky. I have a modern marriage. My wife lives across town in her own house. She has to have her own house and we'll let her put up her shit on her walls. Right? My walls are full.

What is the ultimate legacy of your photography?

The thing that frustrated me was that I wished there would have been more of a financial reward. You know? You've given your best to it. You got to remember the other side of the coin was I didn't do it for the money. I'm a documentary photographer and I wanted to show us as we are, as real people, and that we're a good society. When I did my book

Our Kind of People, I would go and photograph a Junior Women's Club and I would go, 'What are all these women doing here and having lunch and blah blah blah?' And then you realize they are raising money for a high school girl to go to college.

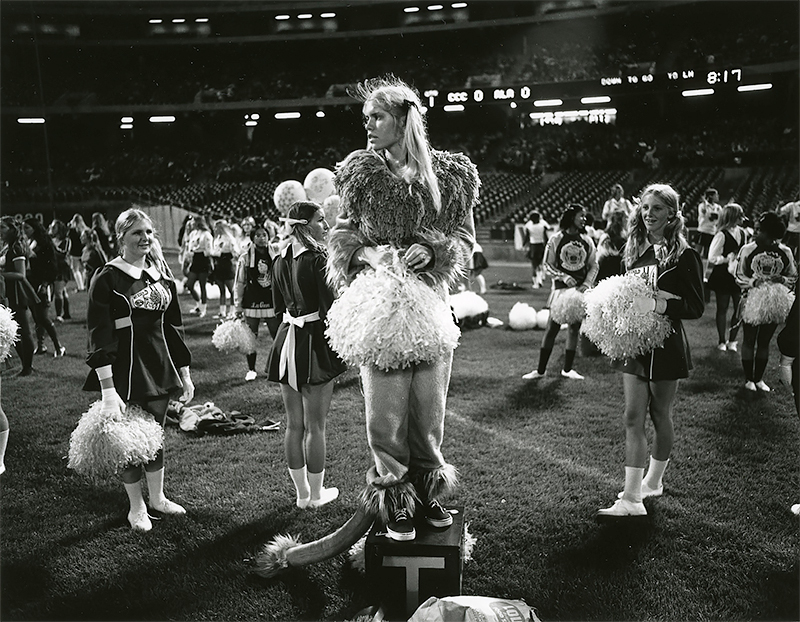

Our Kind of People © Bill Owens

I didn't have any special advantage. In college they give you an IQ test and I'm 101. I'm absolutely normal. But there's a part of me that can't be measured. I'm very ADD or dyslexic. But there's another part of me that's super creative. How did that happen?

Thanks, Bill. I admire you so much.

Our Kind of People © Bill Owens

is a Sarasota, Florida based writer. His three novels and many investigative journalism articles have received a Guggenheim, an NEA, and the NEA Japan Friendship Fellowship. He spends his summers in Dunsmuir, CA, a small railroad mountain town where his wife was born and raised.