An exhibition of women photographers making work about the West featuring images by Christa Blackwood, Mercedes Dorame, Ingeborg Gerdes, Tomiko Jones, Kathya Landeros, Jennifer Little, Mimi Plumb, Kari Orvik and Donna J. Wan

Curated by Ann Jastrab

I've been reading a lot of Larry McMurtry lately, consuming novel after novel as though I won't have enough time to get through them all in this life. At night I can't sleep without visiting the plains alongside the Comanche. I'm not sure what has happened to me, this obsession with the West, but it's a very particular West. It is not the West of Ansel Adams or Edward Weston. I am very clear about this. It's also not a romanticized version of the landscape. Most times, it's a rough, unwelcoming place in my mind. A place without water and with struggling trees, sandy hillocks and rocky outcroppings. A place so wide open that you can see in all directions and this would normally be enough to crush me, but the light is so stark and beautiful that I forgive the land for this rawness.

When the

San Francisco Arts Commission asked me to curate another show for City Hall, I happened to be visiting my parents in Upstate New York. My father and I were driving up to the Adirondacks under a heavy winter sky and he kept saying, 'Look at those mountains!' and all I could see was a rounded, gradual swell on the horizon that didn't even look as big as the hills in my backyard in California... and then I realized that the West and its dramatic beauty and ruggedness had ruined me for subtle landscapes. Maybe ruined me for every place else.

I thought of the photographs I'd made when I first traveled West more than twenty years ago, what shook me to my core, what made me stop and set up my view camera... I then thought of other women photographers and what captivated them about the West. There are so many women who have made the journey or who grew up here and saw the West so differently from their male counterparts. The exhibition, Westward, presents an opportunity to break away from patriarchal representations of the West. Given the West's historical association with Manifest Destiny, a 'masculine' endeavor and the subject of the male-dominated landscape artist field, the ten female artists in this show offer us an alternate vision of this oft documented and depicted region of the United States.

Within these women's various projects, there is a personal connection with the land, with their subjects, with their experience of the West. There is desire and intimacy and a closeness to the land that can make the viewer tremble. It becomes apparent that the photographers were doing more than observing and documenting their surroundings; they were drawn by the light and the scenes around them, so much so that they became embedded in the work.

The projects here are diverse and divergent and yet all are held together by the women's strength of seeing. I begin with

Mimi Plumb's photographs from the 1980s, images from Landfall, Dark Days and The City. For Plumb, the 1980s encapsulated the anxieties of a world spinning out of balance. Global warming, civil wars in the Middle East and Central America, and the election of a former movie actor to the presidency of the United States, all this contributed to the sense of no future.

Her photographs from the 1980s came from the desire to visualize the despair and disillusionment that Plumb was feeling, an expression of a world turned upside down. She made pictures of manmade scars and refuse seen both in the city of San Francisco and the Western landscape. Now, as the effects of climate change have become more urgent and dire, with the election of a reality TV star as the President of the United States, and with the current political and social climate, Plumb's images resonate now more than ever.

© Mimi Plumb - Palm Desert, 1987

© Mimi Plumb - Truckee Canal, 1985

© Mimi Plumb - Pyramid Lake, 1985

© Mimi Plumb - 25th Street Pier Fire, 1985

Then there is

Greta Pratt, who may or may not have read as much Larry McMurtry as me. Her current project,

Cloud of Dust, depicts a West that could be fact or fiction. Much like fake news, fake history becomes a truth that functions to influence the thoughts and belief of the present. For the past three years, Pratt has been photographing the American West to examine western mythology and the elevation of hyper-masculinity.

The iconic male characters of the west, the cowboy, the gunfighter and the lawman embody a code of bravado and violence and yet still hold a nostalgic and populist place in American memory. Recent manifestations of gender, power, and populism in the U.S. make this topic even more provocative. The underlying motivation for all of Pratt's work is the realization that history and national memory influence the present and shape the public's response to current issues and events.

© Greta Pratt - Julee and her Daughters from the series A Cloud of Dust, 2015

© Greta Pratt - Espi's Daughter (Escaramuza dresses), 2014

© Greta Pratt - Boots in a Suitcase, from the series 'A Cloud of Dust', 2014

© Greta Pratt - Fistful of Dollars, from the series 'A Cloud of Dust', 2016

© Greta Pratt - Ashton Old Elk, Relay Rider, 2015

Within

Kathya Landeros' family narrative, there are many tales of generational migration and of hardworking kinfolk who emigrated from Mexico to the United States in search of work (her great-grandfather worked and died in the copper mines of Arizona; her grandfather was a Bracero, part of a bilateral government sanctioned agricultural work program; and her grandmother and parents worked as farmhands in California's Central Valley). This has led to Landeros' interest in visually exploring Mexico to U.S. migration from the perspective of longstanding communities, specifically in the American West where her family and many other Latino immigrants have settled, and continue to do so, due to the history and ongoing presence of agricultural work.

In working on this series of photographs, Landeros' aim is to offer a counterpoint to the traditional views of the American West, to include Latinos within this photographic narrative. And, perhaps, at a time when immigration has become such a contentious issue, these photographs may also serve as a reminder of the contribution immigrants have made, and will continue to make, to the development of this nation.

© Kathya Landeros - 5th Street, Arbuckle, California, 2014

© Kathya Landeros - Main street laundromat, Eastern Washington, 2012

© Kathya Landeros - Ebodio's son, Methow Valley, 2012

work explores the construction of culture and origin stories as outcomes of the need to tie one's existence to the land. Her heritage as a member of the Gabrielino/Tongva tribe in Los Angeles connects her deeply to the landscape of California. She is interested in the problematics of living in a place that once belonged to your ancestors, a place you feel connected to, yet have lost access to. Her tribe has no federal recognition, and therefore no reservation land and no gathering place.

This lack of physical space to congregate in and use for ceremony creates a collection of individuals constantly challenging and grappling with authenticity and inclusion/exclusion from the larger group. By working in spaces Dorame is connected to, she engages ideas of authenticity, ceremony and community. She creates humble interventions in the landscape, using the camera to re-open portals of memory, to reconnect with and to heal the land.

Dorame explores culturally significant sites in Southern California in order to make a new personal narrative. This is necessary because much of her tribe's culture was systematically erased. She hopes to create a narrative that mixes truth and fiction in order to tell her personal history in conjunction to her cultural ancestry believing that the imagined can be equally as powerful as facts.

© Mercedes Dorame - Ascension, 2011

© Mercedes Dorame - Dark Pools, 2013

© Mercedes Dorame - In the Beginning was Fox and Cinnamon, 2011

© Mercedes Dorame - Smoke to Water - Chyaar Paar 'Apuuchen, 2013

The overarching element throughout

Tomiko Jones' work is a relationship to place, a loose mapping that echoes the internal terrain. Water is ever present, shaping her identity. It represents generational migration from Japan to Hawai'i to California, to Washington and is imaged in photographic works. She herself is an explorer, born and raised. Every summer, Jones' father would pile her family into the car and take them to explore the treasures of the nation, our public lands. In the most classic of touristic gestures they would set forth in a camper. They visited feats of human engineering – dams, bridges and buildings were favorite stops on their way to admire feats of nature such as Yellowstone, Yosemite and Niagara Falls. Many miles of open land lay between their excursions, and watching the American landscape pass by had a profound effect on Jones over the years. She would want to stop and explore, but as her family was always headed for a destination, there was never enough time. This created in her a longing to return. Jones now has a camper of her own and is exploring the geography of the West, its destruction and reclamation, the transitional places between land and water, and she can now take as much time as she wants to document these changing landscapes. She also inserts herself in these landscapes in a way that is quite a surprise.

© Tomiko Jones - Rattlesnake Lake, 2014

© Tomiko Jones - Rattlesnake Lake #2, 2014

© Tomiko Jones - Rattlesnake Lake #3, 2014

The first time I saw

Donna J. Wan's large color landscapes, I thought how sublime they were, how visceral, how seductive. I didn't realize, for years actually, that the photographs from her project, Death Wooed Us, were images of suicide destinations. The photographs in this project attempt to capture the views of these settings. Using research gathered from media reports, Wan found several locations in the Bay Area and travelled to them. She walked along the paths taken by these people before they ended their lives. Most of these photographs were taken from bridges, including the Golden Gate Bridge, one of the most well-known suicide destinations, but also lesser-known beaches and overlooks. She purposely photographed from the perspective of looking up at the sky, down at the water or crags, or straight ahead but far away, thinking that these views might have resembled the ones seen by others moments before dying. Many of her images have a hazy and elusive quality, which Wan believe reflects the clouded state of mind of the suicidal.

There are some who may think that Wan's photographs romanticize these places of death. That is not her intention. She knows death is not beautiful. Yet the sublimity of these places continues to lure people to them. I myself stood with my brother on the Golden Gate Bridge just months before he would finally kill himself and I saw something in his expression as he looked out over the water, something unrecognizable and eerie, but also blissful, and I knew that death was wooing him. As the poet Louise Gluck wrote in her poem, Cottonmouth Country, Death wooed us, by water, wooed us by land...

© Donna J. Wan - Dumbarton Bridge #3, 2014

© Donna J. Wan - Golden Gate Bridge #1, 2013

has also wandered far and wide in creating her images of the West. There is one diptych of the shattered dream of gold in the hills, or really, the reality of the life of the land and the hand of man upon this exhaustible resource, that makes these untraditional landscapes of Kari Orvik's Alaska so riveting. What about Denali and the wilderness? No, here in her home place of Fairbanks, the land is dug up and moved aside. Instead of a mountain, it is a giant mound of dirt with one half of the diptych seeming to be spring, the other winter. Knowing Orvik as an artist, I wonder how this experience with the landscape shaped her and her vision. That perhaps things on the ground aren't as good as they are from the air, the close-up view desolate. Yet there is no yearning for someplace else in these pictures. This is just what is left in her native Alaska.

© Kari Orvik - Birch Walk from the series 'Exercises for Moving in Between' Fairbanks Alaska, 2013

© Kari Orvik - Birch Leak

© Kari Orvik - Gold Hills 1, Fairbanks Alaska, 2013

© Kari Orvik - Jody's Mine, 2014

came to the United States from Germany and set out on multiple road trips to capture this foreign place that would become her country. Her images from Out West Across the Basin depict a West that is at times tamed and at times unbroken. Horses peer into doorways of farmsteads and a taxidermied antelope stands propped on its base on the side of the road while tired families scale a mountain of lava, a cinder cone that seems to have buried every other living thing. And then around the next bend, there are a thousand birds covering the surface of a lake and then a plain covered in dense chaparral with a hundred lost sheep peering back at Gerdes. She has discovered a West that is at once embattled and wild. I go back through her pictures again and again to find that what happened out there across the basin in the West was magically witnessed by Gerdes and her camera.

© Ingeborg Gerdes - Clarksdate Arizona, 1989

© Ingeborg Gerdes - Craters of the Moon Idaho, 1988

current project, 100 Years of Dust: Owens Lake and the Los Angeles Aqueduct, is an in depth documentation of the environmental and political conflicts over water rights and air quality in California's Owens Valley. Little's photographs are beautiful and heart-breaking and raw. I think of her standing in the middle of a dust storm unflinching, the power of the scene unfolding before her. She has discovered some secrets about the land and the water in the great state of California and she's not afraid to reveal them to her viewers.

Owens Lake lies in California's Eastern Sierra Nevada Mountains, about 200 miles northeast of Los Angeles. This 110-square-mile lake began to dry up in 1913 when Los Angeles diverted the Owens River into the Los Angeles Aqueduct. The new water supply allowed Los Angeles to grow and turned the arid San Fernando Valley into an agricultural oasis, but at a tremendous environmental cost. By 1926, Owens Lake was a dry alkali flat, and its dust became the largest source of carcinogenic particulate air pollution in North America. In 1998, the EPA mandated that the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) take steps to minimize the toxic PM-10 dust pollution from Owens Dry Lake. This pollution was 100 times greater than federal air safety standards. LADWP began construction on the Owens Lake Dust Mitigation Project in the year 2000. They have installed 50 square miles of dust mitigation zones, including gravel cover, managed vegetation, buried drip tubing, and irrigation bubblers to shallow flood the dry lakebed. This dust mitigation project has cost $1.6 billion to date and requires so much water that it may not be sustainable as climate change results in a drier climate for California.

© Jennifer Little - Erosion Along Symmes Creek, Tributary to Los Angeles Aqueduct, Owens Valley, CA, 2015

© Jennifer Little - Shallow Flood Irrigation Bubbler, Owens Lake, CA, 2014

© Jennifer Little - The Owens River and LA Aqueduct Diverge at the Aqueduct Intake, Owens Valley, CA, 2016

The West would not be the West without its rugged landscapes and also its ingenuity.

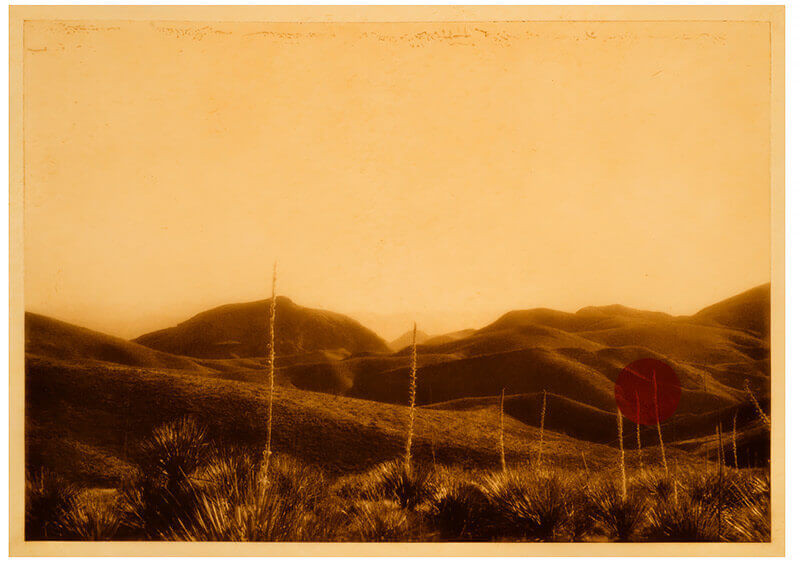

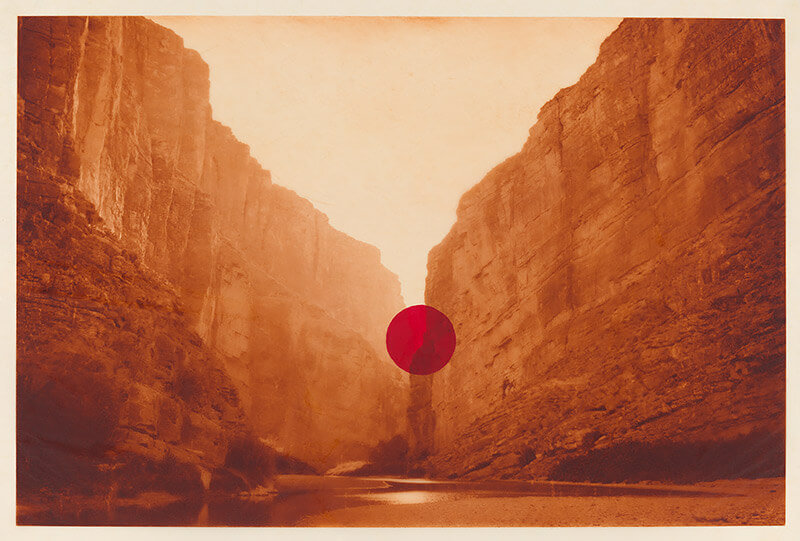

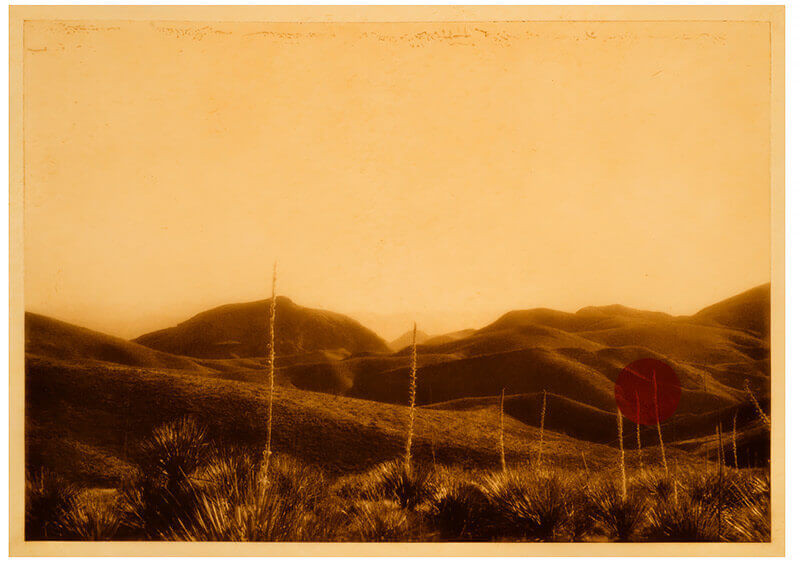

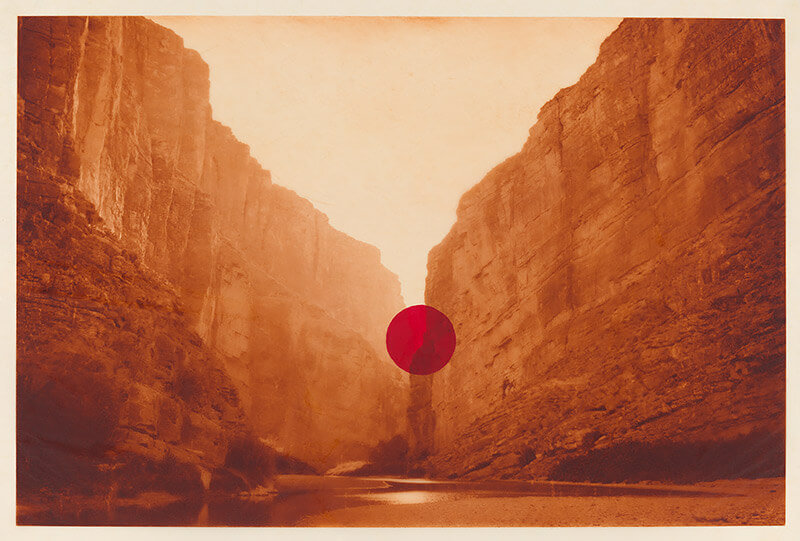

Christa Blackwood, a native Texan, created her red dot series with a new perspective on the traditional genre of landscape. Blackwood's work (hand-pulled photogravures with applied paint) employs historical techniques and yet redirects the viewer with the red circle. I braced myself at the beauty of these prints and then was pulled in by the mystery of the painted sphere. Exploring the idea of the figure with a red dot, backgrounded by historical landscape photographs, tradition and contemporary theory meet and mingle and also struggle. To quote W. Tanner Young, These traditional landscapes – historically photographed by men - act as metaphor for a male view, and through this the feminine metaphor of the red dot emerges and creates a visual enigma which deliberately defies this tradition. Often portrayed as nudes, the female body or figure in photographs stands in stark contrast to the portrayal of men - who are often the ones taking the portraits - famous male photographers such as Weston, Steiglitz, Man Ray, etc, who commonly employed the male gaze approach. Here Blackwood turns this upside down and shifts the focus of attention and enables a reconsideration of the classical subjects.

© Christa Blackwood - Notorious

© Christa Blackwood - Santa Elena Canyon

When I journey through the stories that these women have laid before me, my mind reels. So much anguish and darkness and beauty and humor and destruction and loss and examining and ultimately understanding... it's a lot to take in and a lot to consider.

I flew 3,000 miles last night and as the land grew flatter and the plane neared the Atlantic, I thought of the pull of the West and the lure and legend of it as well. I thought of this show and its subtleties and its strengths and the journeys of the artists and I paused in my index of pictures and opened the McMurtry book (Comanche Moon, if anyone is curious) to page 613 and continued to travel across West Texas in search of something not quite tangible, but oh so powerful.

Westward will be on view at San Francisco's City Hall for a whole year, from May 11, 2018 – May 10, 2019, so make sure to stop by and see it if you're in the Bay Area.