From February 24 to June 14, 2026, the

J. Paul Getty Museum presents Photography and the Black Arts Movement, 1955–1985, a landmark exhibition exploring how photographic practices helped shape one of the most influential cultural movements of the twentieth century. Organized by the National Gallery of Art, the exhibition reveals how artists across the African diaspora used images not simply to document history, but to transform it.

Uniting around the civil rights struggles of the mid-1900s, writers, musicians, and visual artists sought new ways to celebrate Black identity while advocating dignity, freedom, and self-determination. Their collective creative force became known as the Black Arts Movement — a cultural revolution that redefined representation and demanded visibility on its own terms. Photography, with its immediacy and accessibility, became one of its most powerful tools.

Genie, 1971, printed later Ray Francis, (American, 1937–2006) Gelatin silver print J. Paul Getty Museum© Estate of Ray Francis

Bringing together more than 150 works spanning photography, painting, collage, video, magazines, and ephemera, the exhibition demonstrates how images circulated through communities as catalysts for change. According to Getty director Timothy Potts, the works show how artists and activists “tapped the power of photography” to confront inequality and strengthen respect for Black culture during a turbulent historical moment.

The exhibition highlights a remarkable range of artists, including painters such as Frank Bowling and David Driskell, alongside photographers like Kwame Brathwaite and Roy DeCarava, whose images helped redefine visual narratives of Black life. Works by Los Angeles figures such as Betye Saar and Charles Gaines further underscore the West Coast’s vital contribution to the movement’s visual language.

Eight Sections Mapping a Cultural Revolution

Structured into eight thematic sections, the exhibition traces how photography functioned simultaneously as art form, political instrument, and communal archive:

Picturing the Self / Picturing the Movement explores self-representation as an act of empowerment, countering distorted mass-media portrayals.

Fashioning the Self examines style as political expression across the diaspora.

Representing the Community reveals how everyday life became a site of pride and resistance.

About Looking focuses on experimental visual strategies that challenged perception.

Activism shows how documentary photography mobilized public support for civil rights.

In the News highlights the global circulation of protest imagery through magazines and television.

Transformation in Art and Culture traces how artists seized control of visual narratives.

California Connections spotlights Southern California’s networks of Black artists, including collectives and alternative spaces that bypassed exclusionary institutions.

Together, these sections reveal photography as both witness and participant — shaping public opinion, preserving memory, and strengthening solidarity across borders.

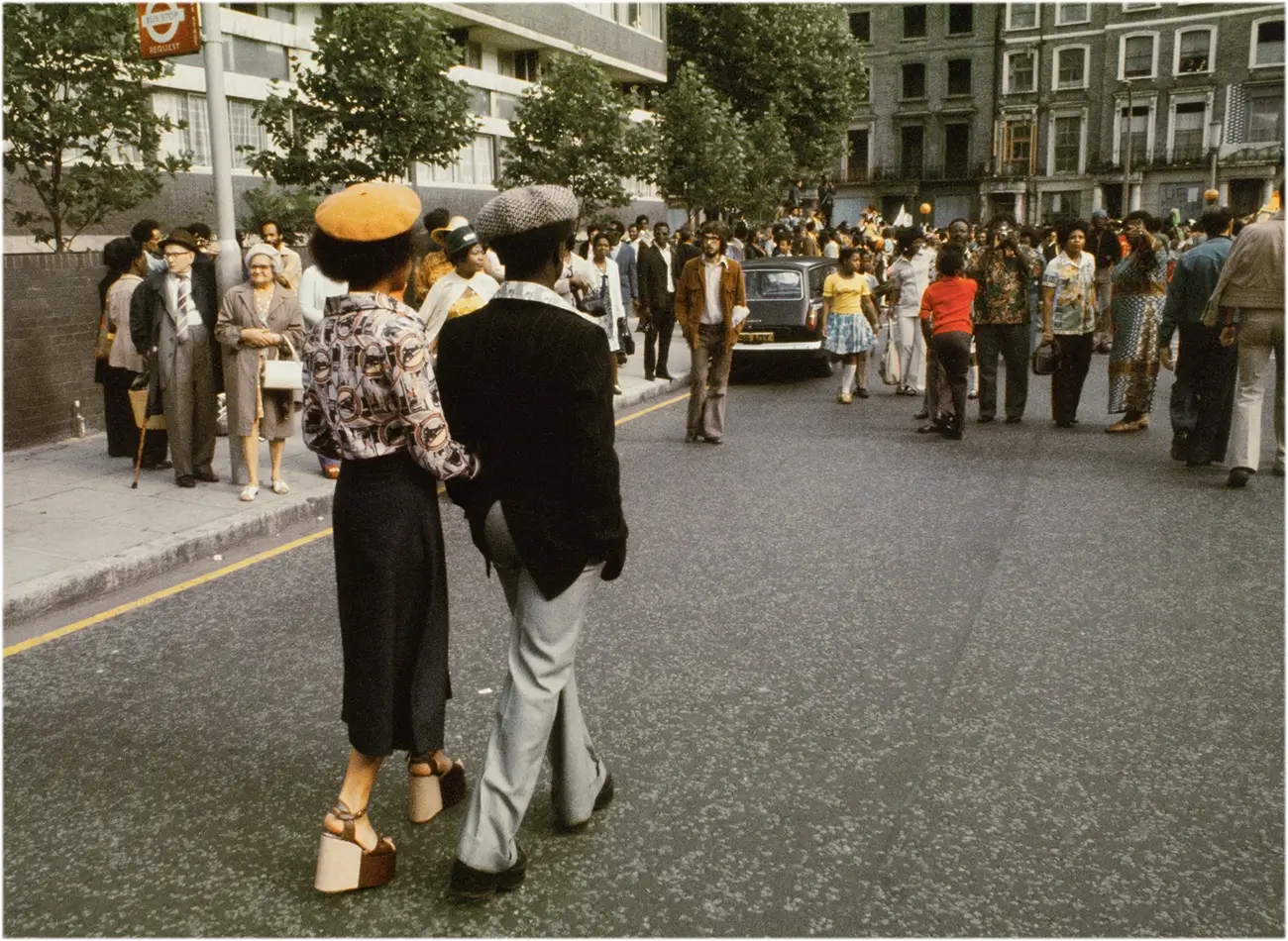

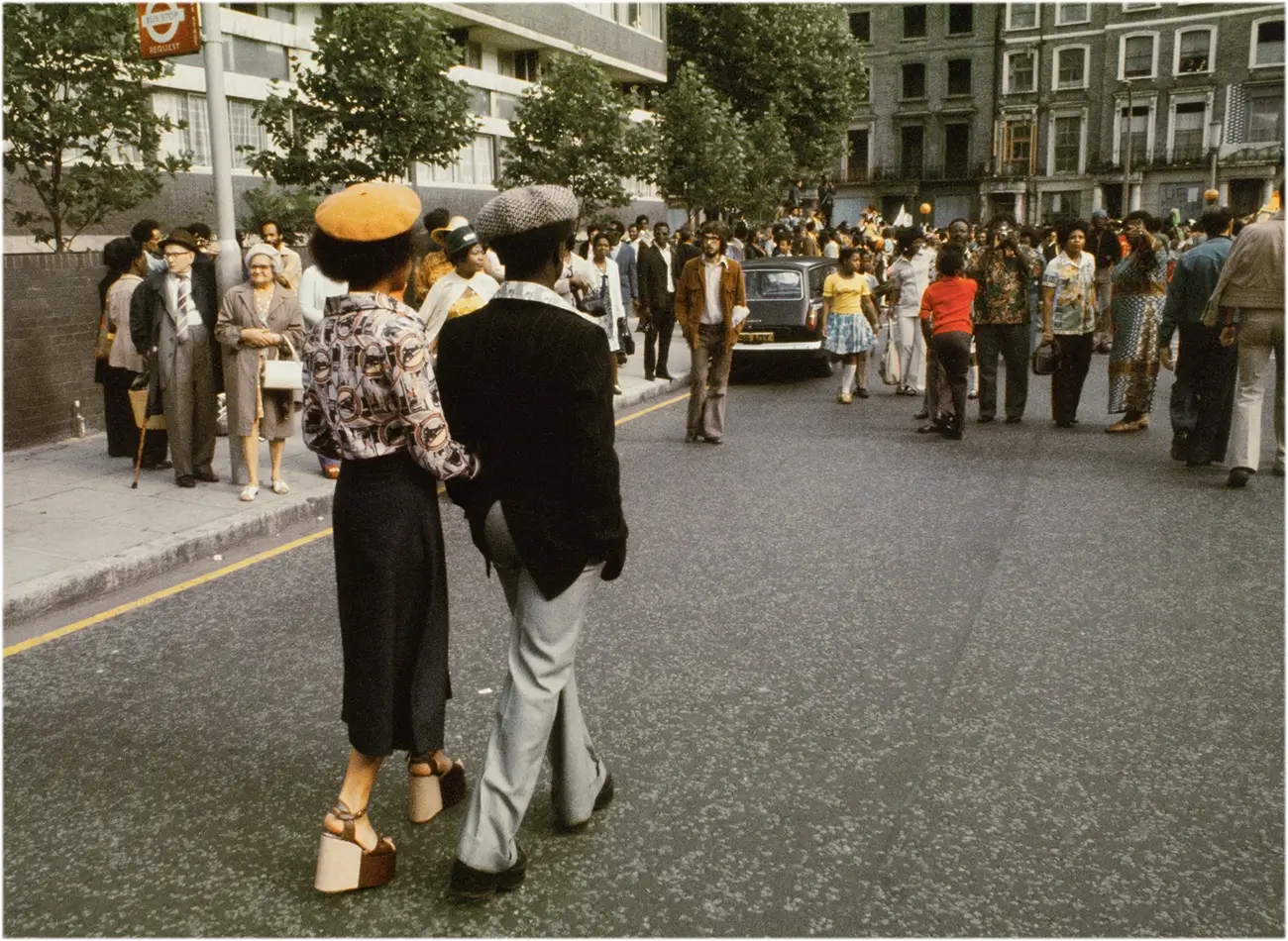

Walking Proud, Notting Hill Carnival, about 1972, printed 2023 Horace Ové (British, born Trinidad, 1936–2023) Inkjet print National Gallery of Art, Washington. Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund, x2025.43.3 © Sir Horace Ové

While many works radiate joy, style, and resilience, the exhibition does not shy away from difficult histories. A striking installation by Adrian Piper reproduces newspaper clippings of wars and disasters inside a confined room stamped with the phrase “NOT A PERFORMANCE,” forcing viewers to confront the uneasy relationship between art, politics, and spectatorship.

Curators, Conversations, and Cultural Programs

The exhibition is curated by Philip Brookman and Deborah Willis, two leading authorities on photography and visual culture, and overseen in Los Angeles by Mazie Harris. Opening day programming includes gallery discussions with artists and a screening of Horace Tapscott: Musical Griot by filmmaker Barbara McCullough, followed by a conversation on African American art history.

The exhibition coincides with Black History Month celebrations and a broader series of performances and talks, including programs honoring experimental artist Benjamin Patterson and musical collective Jimetta Rose & the Voices of Creation.

Protest Car, Los Angeles, 1962, printed 2024 Harry Adams (American, 1918–1985) Inkjet print Harry Adams Archive, Tom & Ethel Bradley Center, California State University, Northridge © Harry Adams. All rights reserved and protected.

More than a historical survey, Photography and the Black Arts Movement, 1955–1985 offers a timely reminder of photography’s enduring role in social change. Long before the era of viral imagery and digital activism, these artists understood the camera as a device of agency — capable of reclaiming narratives, strengthening communities, and challenging injustice.

By bringing together decades of visionary work, the exhibition demonstrates that photographs are never neutral. In the hands of artists committed to justice and representation, they become instruments of transformation — images that do not merely record history, but help write it.

Above This Earth, Games, Games, 1968 Ralph Arnold (American, 1928–2006) Collage and acrylic on canvas Collection of Museum of Contemporary Photography at Columbia College Chicago Photo: P.D. Young / Spektra Imaging

Ethel Sharrieff in Chicago, 1963, Gordon Parks (American, 1912–2006) Gelatin silver print National Gallery of Art, Washington. Corcoran Collection (The Gordon Parks Collection), 2015.19.4631 © Gordon Parks Foundation