For over 20 years, the La Gacilly Photo Festival has been a key contributor to the vitality

of a rural community. It is now recognised as a major event by the Morbihan Council.

This 21st edition stays consistent with its editorial focus and showcases a diversity of

photographic visions.

The Festival is spearheaded by a team of passionate individuals, with invaluable support

from volunteers and backing from public and private partners. It is a unifying force that

brings together photographers, various stakeholders, and the community around a set

of shared values.

Photography is an art to be shared, as proven each year by the 300,000 festival-goers

who come to admire the talent of the photographers and their works on display along the

narrow lanes and streets and in the gardens of our village.

What sets the La Gacilly Photo Festival apart is not only that it highlights social and

environmental issues, but also the fact that it is rooted in a close-knit, welcoming community.

This year, we are also celebrating the seventh year of the La Gacilly-Baden Photo Festival,

a sign of our efforts to give our event international reach.

In the name of all the members of our association, I would like to express my gratitude for

the dedication and commitment demonstrated by everyone involved in this remarkable

project.

Jacques Rocher

President and Founder of the La Gacilly Photo Festival

Australia

BOBBI LOCKYER: Origins (Australia b. 1986)

Bobbi Lockyer is, in her own words, a pink-haired mermaid queen, feminist, queer and

passionate about colour, working to shake up traditional social circles with her art.

An art she creates using clothing, traditional works (material and digital), paintings…

and photographs.

Born in Port Hedland in Kariyarra country, she is a representative of the Ngarluma,

Kariyarra, Nyul Nyul and Yawuru peoples. Honoured as a NAIDOC Artist Celebrating

Aboriginal Culture in 2021 and an Ambassador for Nikon Australia, Bobbi Lockyer

draws inspiration from ancestral tales, the vibrant hues of her natural environment, the

waves of the ocean and her deep commitment to her community, using all this to fuel

an artistic approach that defies convention.

She offers a glimpse into the intimate through her work, which also serves as a

platform to advocate for causes close to her heart, such as social justice, the rights of

indigenous peoples and women’s rights, including Birthing on Country: a movement

that helps Aboriginal women give birth in a familiar environment that respects their

traditions and identity. This concept also affirms that the child is born on the sovereign

lands of Australia’s first peoples, peoples who have never ceded ownership of their

lands, seas and skies to anyone else. These notions of motherhood, transmission and

natural heritage hold great importance for this artist, who is well aware that the survival

of the first peoples depends on the preservation of their ancestral rites.

This is also a necessary struggle: in 2023, after a historic referendum, Australia voted

“No” to constitutional recognition of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

as the original inhabitants of the island-continent. A failure at the end of a campaign

that further deepened the racial divisions in the country.

www.bobbilockyer.com

Big Sky series. Australia was, and will always be, Aboriginal land. © Adam Ferguson

In 1979, photographer Richard Avedon started to spend his summers roaming the

American West, taking portraits of the people who lived there. This work was exhibited in

1985 and helped to debunk the myths of the American Wild West, forged by post-Civil War

literature, music and film, which romanticised a dangerous world populated by “savages”.

Australian photographer Adam Ferguson, who returned to his native country after

covering conflicts (in Afghanistan, among other places), wanted to emulate exactly this

approach in his Big Sky series. The title evokes the very particular ambience in the vast,

sparsely populated Australian territory: “There’s kind of an eerie quietness to it,” he

warns. “And the expanse of sky becomes incredibly loud and poignant.” His aim was

to explore the complex interplay between Australia’s colonial history and the current

climate crisis, globalisation and contemporary daily life in the country’s rural expanses.

“As Australians, integral to our national psyche is this notion of the bush and the

farmer and the outback,” says Adam Ferguson. “And that’s been pretty pivotal

in developing, at least, an Anglo national identity.” But in his view, this national

narrative is far removed from reality. In particular, he mentions farming methods

inherited from the English model, which do not fit the Australian ecosystem.

Of the view that no one had really photographed the interior of Australia in the way that

Avedon had captured the American west, Ferguson set out to follow his predecessor’s

lead and portray his homeland in a new light. And to recognise that these territories

still belong to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples – the two indigenous

groups of Australia. A form of respect: “We recognise that the sovereignty of this land

has never been ceded and we pay tribute to the elders, past and present. It was, and

always will be, Aboriginal land.”

adamfergusonstudio.com

A kangaroo tries to escape the flames, in front of a burning house near Lake Conjola, in New South Wales, the Australian state most severely affected during the bushfires of 2019-2020. An image published worldwide and awarded at the World Press Photo.. © Matthew Abbott

Between June 2019 and May 2020, the bushfire season in Australia was so violent that

specialists dubbed it “Black Summer”. With 24.3 million hectares ravaged, more than

3,000 buildings destroyed, 88 billion Australian dollars in financial losses, 34 people

killed and 3 billion terrestrial vertebrates killed, it was one of the greatest disasters in

the country’s recent history.

Photographer Matthew Abbott captured the tragic event and won a World Press Photo

award for his image of a kangaroo hopping past a burning house.

At the time, many members of the government tried to deny or ignore the link between

climate change and the increase in the number and scale of fires. However, in an article

published in the scientific journal Nature in 2021, a group of researchers demonstrate

that fire activity in Australia is strongly influenced by high climate variability, and that

climate change has the potential to further alter the dynamics of these fires.

Confronted with this reality, could the answer lie in the ancestral practices practised by

the Aborigines since time immemorial? This indigenous people, whose culture is one

of the oldest on the planet, has revived the ancient practice of burning to preserve and

improve their native lands – and contribute to the development of their communities.

These practices have been analysed and refined by scientists who now endorse them.

At the start of the dry season, these men and women do not therefore fight fires.

They start them, to maintain better control of the flames afterwards. As the number of

forest fires continues to rise, fire is being reconsidered as a solution, and not just a

problem.

@mattabbottphoto

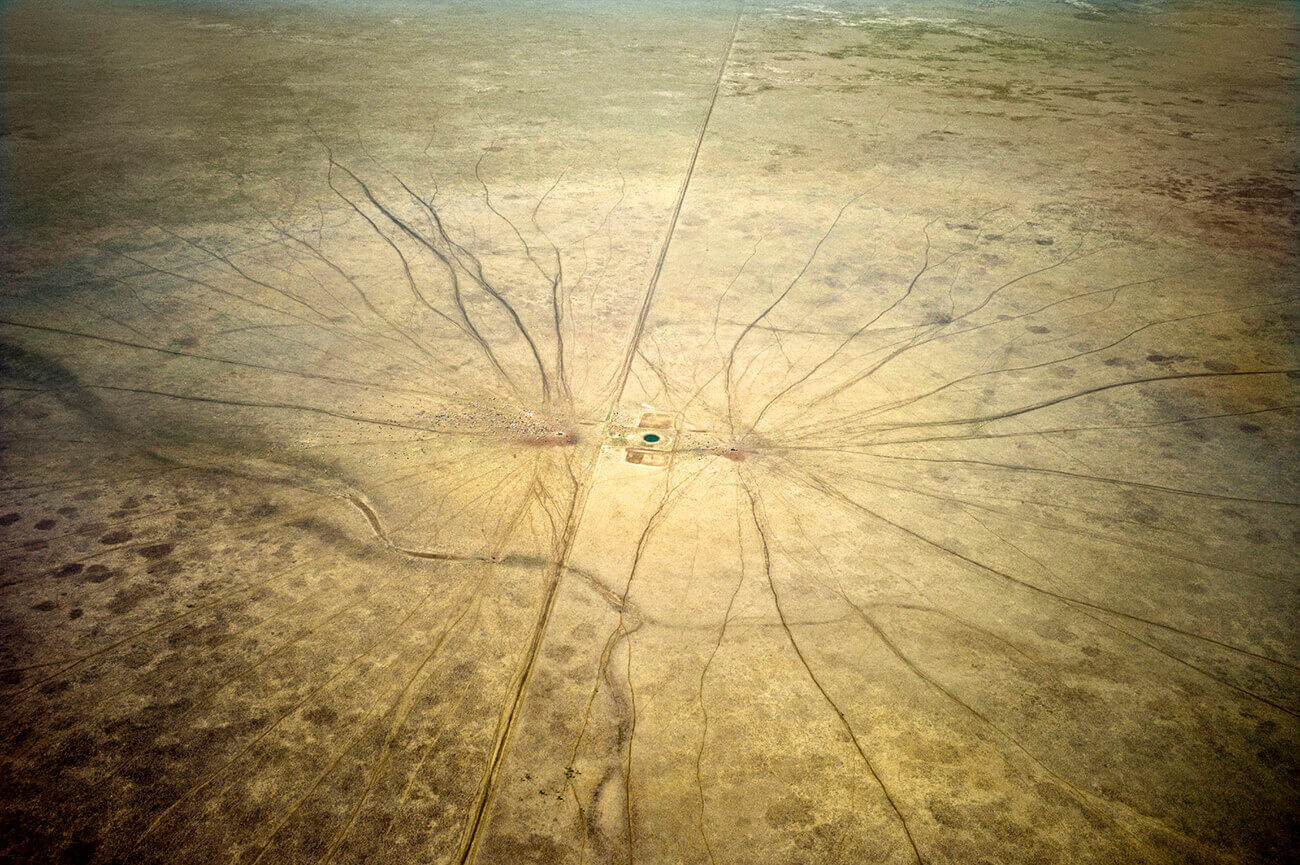

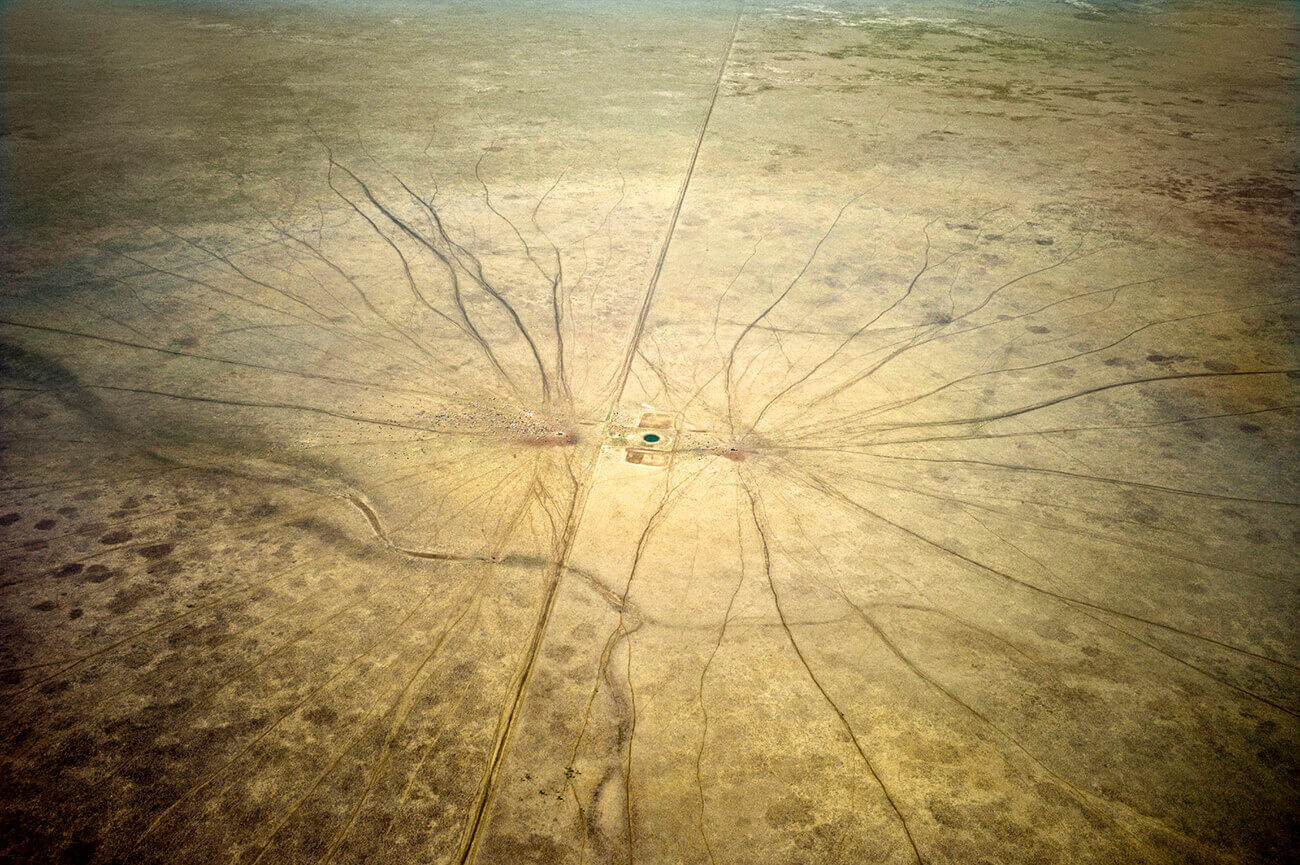

Well in the middle of the Australian desert to water the herds. Northern Territory, Australia, November 2011. © Viviane Dalles

This Latin expression refers to a land unoccupied by any state, a “nobody’s land”.

The principle of terra nullius emerged when the British colonised Australia, to justify their

invasion of this island-continent, considering the indigenous people as an inferior race

destined to become a just a small segment of the population, or indeed, to disappear

altogether. On 28 April 1770, British explorer James Cook refused to recognise the

indigenous populations. Two centuries later, in 1992, a legal battle over the recognition

of Aboriginal land rights led the High Court of Australia to deliver a landmark judgement

declaring that the country had never been terra nullius and invalidating this principle,

with retroactive effect.

Today, Australia has a population of over 25 million. The vast majority live on the

coast, in the big cities such as the capital Canberra, Sydney and Melbourne.

Nearly 10% live in the heart of the country – the Bush and the Outback – covering more

than two-thirds of the territory. Viviane Dalles, the French photographer who won the

Canon Women’s Photojournalist Award, set out to understand how the sparse population

of these deserted regions live, and spent several months in this vast wilderness.

Most of her story takes place in the Northern Territory. A place where time and distance

stretch infinitely like the horizon. A few towns remain, such as Alice Springs, the

gateway to the Red Centre. But Viviane Dalles left these places behind, instead taking

to the dusty roads, where life gains a whole new dimension. Living on a vast farm,

comparable in size to a French département, demands extraordinary self-reliance and

mental strength. Here, far from everything, the children don’t go to school; instead,

school comes to them via the internet and Skype. It’s an immensity that’s harsh yet

magnificent, fierce yet radiant. Hostility that can be tamed… if you take the time.

www.vivianedalles.com

Western Australia. Highway One. Denham. Emus running through a caravan park. The white surface is made up of crushed shells. 2006 © Trent Parke / Magnum Photos

“For me, it’s all about emotional connection. I love this country, love the people,

everything about it… I’m not really interested in any other country…”. Such is Trent

Parke’s proclamation of love for his native Australia. He was born in Newcastle, a town

in New South Wales, not its English counterpart. He got into photography at the age

of 12, using his mother’s Pentax Spotmatic and turned the family laundry room into

a makeshift darkroom. It’s a passion that has stayed with him ever since. He started

out as a photojournalist, working for the press. He has since drawn on his Australian

roots to produce documentaries, along with more intimate works on the borderline

between fiction and reality, exploring themes of identity, territory and family life.

In 2007, he became the first photographer from the country to be admitted to the

prestigious Magnum agency. Parke’s reputation stems from his ability to capture

an authentic, unfiltered portrait of his homeland, which he documents from the

rural outback to the largest coastal cities. For his book Minutes to Midnight, he

travelled 90,000 kilometres across Australia with his partner Narelle Autio (also

exhibiting at this year’s festival in La Gacilly). The result is a work that shows

a nation in flux, uneasy with its identity and its place in the world, but also a work

of fiction that depicts the construction and resurgence of an apocalyptic world..

In another of his series, Welcome to Nowhere, selected for this exhibition, the author

has assembled ironic and often humorous glimpses of dusty hinterland towns, where

the impact of human settlement on the landscape produces some absurd and often

surreal scenes.

All About Trent Parke

Warm westerly winds blow spray from the tops of the waves back onto swimmers. Australie, Sydney, Freshwater Beach, 2001 © Narelle Autio / Agence VU’

Australia is surrounded by three of the world’s five oceans: the Indian, Southern and

Pacific. Few photographers have documented the interactions between humans and

the oceans as subtly as Narelle Autio.

She has spent more than 20 years capturing instants in the water, all while fulfilling

assignments for various newspapers and magazines she has worked for. Her Coastal

Dwellers series earned her a first prize at the World Press Photo Awards and the Leica

Oskar Barnack prize in 2002. She is best known for her study of the human body

interacting with water, creating images that portray people seemingly transported and

distorted by their underwater environment, caught in a cloud of air bubbles that give

the scene a kind of surrealist abstraction.

Autio’s photographs highlight that feeling of fascination mixed with fear we feel when

swimming – whether in the ocean or a pool. They illustrate our natural attraction to

water, always juxtaposed with the profound vulnerability of humans in this element.

In this respect, the water holes – enigmatic oases surrounded by deserts – embody

a sublime contradiction for her: a place where opposing elements converge, where

mystery and the promise of a new world come together beneath the surface. In these

dark waters, everything merges: light and darkness, life and death, questions and

unattainable answers.

The exhibition also features images produced by the artist during her travels across

Australia, along dusty roads that seem to go nowhere, but ultimately lead to one of the

three oceans bordering this island-continent.

agencevu.com/en/photographer/narelle-autio

A colony of boffins 2020 dye sublimation transfer on fabric in light box 265cm x130cm © Anne Zahalka

It’s hard to sum up Anne Zahalka’s forty-year career in a single exhibition. This artist’s

work is held in the collections of the most prestigious museums in Melbourne, Victoria,

Prague and Seoul. She made a name for herself on the Australian art scene with

her eclectic series, which range from still life to hyper-realistic portraits and even

scenes from the natural world. She says that main aim of her work is to explore cultural

stereotypes and use humour to challenge them. She embraces the themes of identity,

belonging, loss and the passing of time. Here, the focus is on her approach to the

natural world.

In her latest work, Future Past Present Tense, for example, she revisits the notion of

diorama: a panoramic painting on canvas, usually presented in darkened rooms to

give the illusion of reality and movement through the play of light. Zahalka has dusted

off these compositions, nowadays found in old museums, and inserted the original

diorama makers – the scientists, illustrators and craftsmen who produced them – into

the scenes. Inspired both by the naturalists of yesteryear and by fictional artists, she

uses photography to draw attention to the drastic changes in Tasmanian ecosystems

and the role of humans in the degradation, or preservation, of this environment. The

animals she portrays are threatened by urbanisation, by the damaging effects of the

climate, by our own folly.

In these images, exhibited for the first time in France, Zahalka constantly manipulates

and exploits the past to better understand the present and thus perhaps provide insight

into the future. Through them, we are encouraged to reflect on the ways in which we

interact with the world – and the world we leave for future generations.

zahalkaworld.com.au

TAMARA DEAN: In Search of an Eden (Australia b. 1976)

In Australia, the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 was compounded by an earlier trauma:

the devastating bushfires of “Black Summer”. Like many others, Tamara Dean’s life was

transformed, disrupted and interrupted. To escape the anxieties induced during this

troubled period, this artist, performer and photographer created a series of shots in

various gardens, using her body as the “illuminated point” in the landscape. “I immersed

my body in the frigid water, buried myself in crevices in the earth, and enveloped my

body in blossoming flowers… and their industrious bees,” says Tamara Dean. “At the

end of each day my body was marked with bruises, scratches and bites, yet I emerged

from the experience re-energised by the intimate physical sensation of being alive.”

“The figure you see moving through the landscape in these works is not just me but

the woman I would like to be. She who can fly through the air, tumble through the

treetops and climb trees.”

Tamara Dean’s signature style uses the body as a symbol. It is a tool used to break down

the barriers separating humanity from its responsibility to the planet. Growing up near

a nature reserve, she nurtured a strong passion for the Australian bush that continues

to motivate her today. By placing humans at the centre of these wild frescoes, she

returns them to their primal state – their status as a species surviving on a planet and an

integral part of a sensitive ecosystem. “By becoming aware of this, we can start to see

ourselves as part of something bigger, and no longer as the centre of the universe.”

All About Tamara Dean

ANOEK DE GROOT, SAEED KHAN, TORSTEN BLACKWOOD: Survivals (Australia)

More than 60,000 years after their settlement on the island-continent, the indigenous

peoples continue to be marginalised on their own lands. Last October, a referendum

was held, with the modest aim of creating an Aboriginal Voice – a mere advisory body

to the government and parliament, with no decision-making powers. It was widely

rejected by Australian voters. Proof that the country is far from having made peace with

its colonial past, as historian Romain Fathi, from the University of Adelaide, explains:

“What can you expect from a nation that still has the Union Jack on its flag and when

its national holiday marks the day it was invaded by the British on 26 January 1788?

They are afraid that the land they stole will be taken away from them.”

As a result, the Aborigines, who today represent 3.5% of the Australian population, are

effectively second-class citizens: their life expectancy is almost ten years shorter than

that of the rest of the population, and they consistently fall behind on all the economic

indicators, from poverty to unemployment, and from poor housing to infant mortality.

The true strength of Agence France-Presse and its network of 450 photographers

worldwide lies in their ability to shed light on news that may otherwise go unnoticed,

sometimes showing what we would prefer not to see, combating preconceived ideas in

the name of truth, telling stories about our changing societies, and catalysing emotions.

And this holds true for the peoples of Oceania, and Australia in particular. Behind the

picturesque folkloric images taken by photojournalists lurks a sad reality. The brutal

truth can sometimes be summed up in a single photograph, like the one taken by

Anoek de Groot capturing the forlorn gaze of a child living in squalor in an insalubrious

camp in Alice Springs.

And Beyond

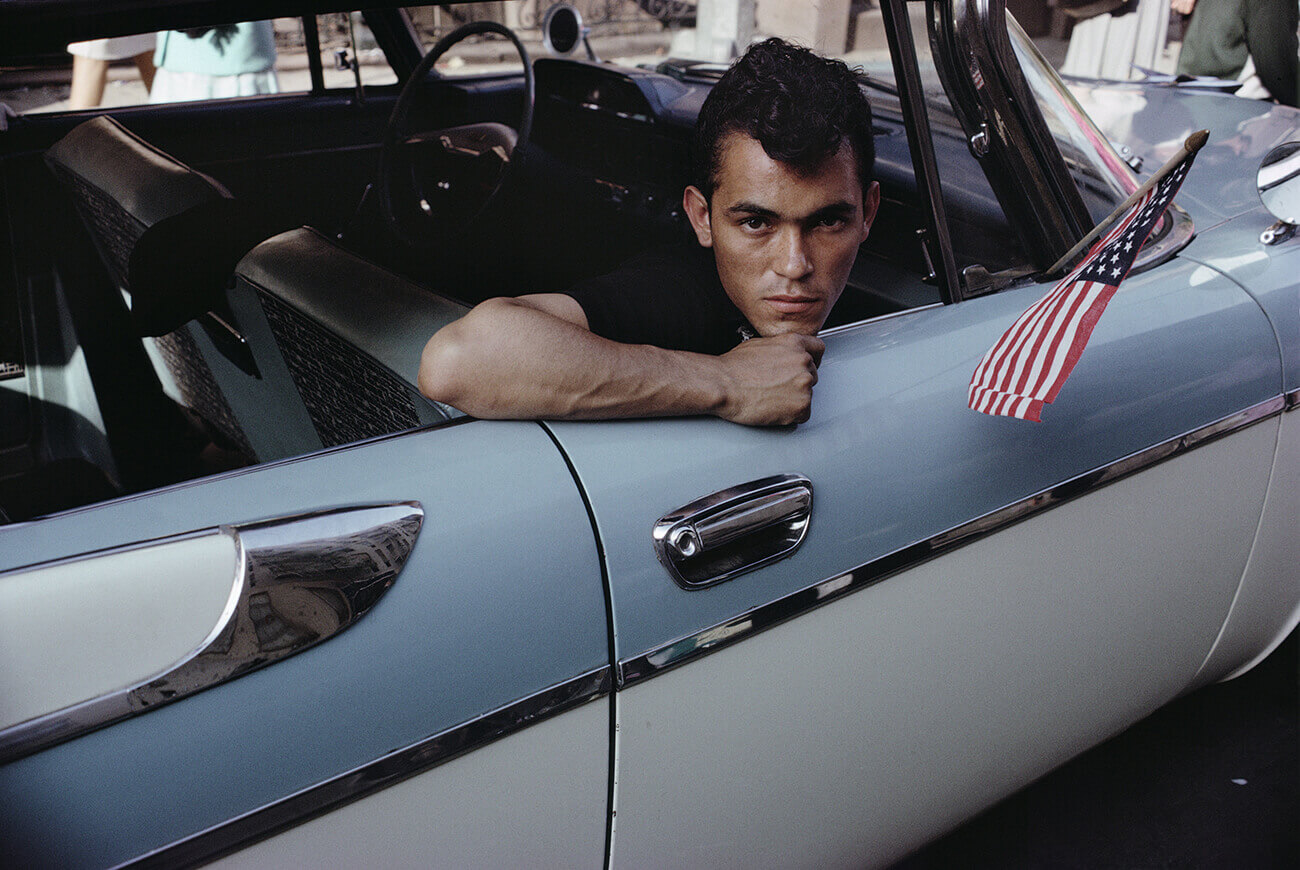

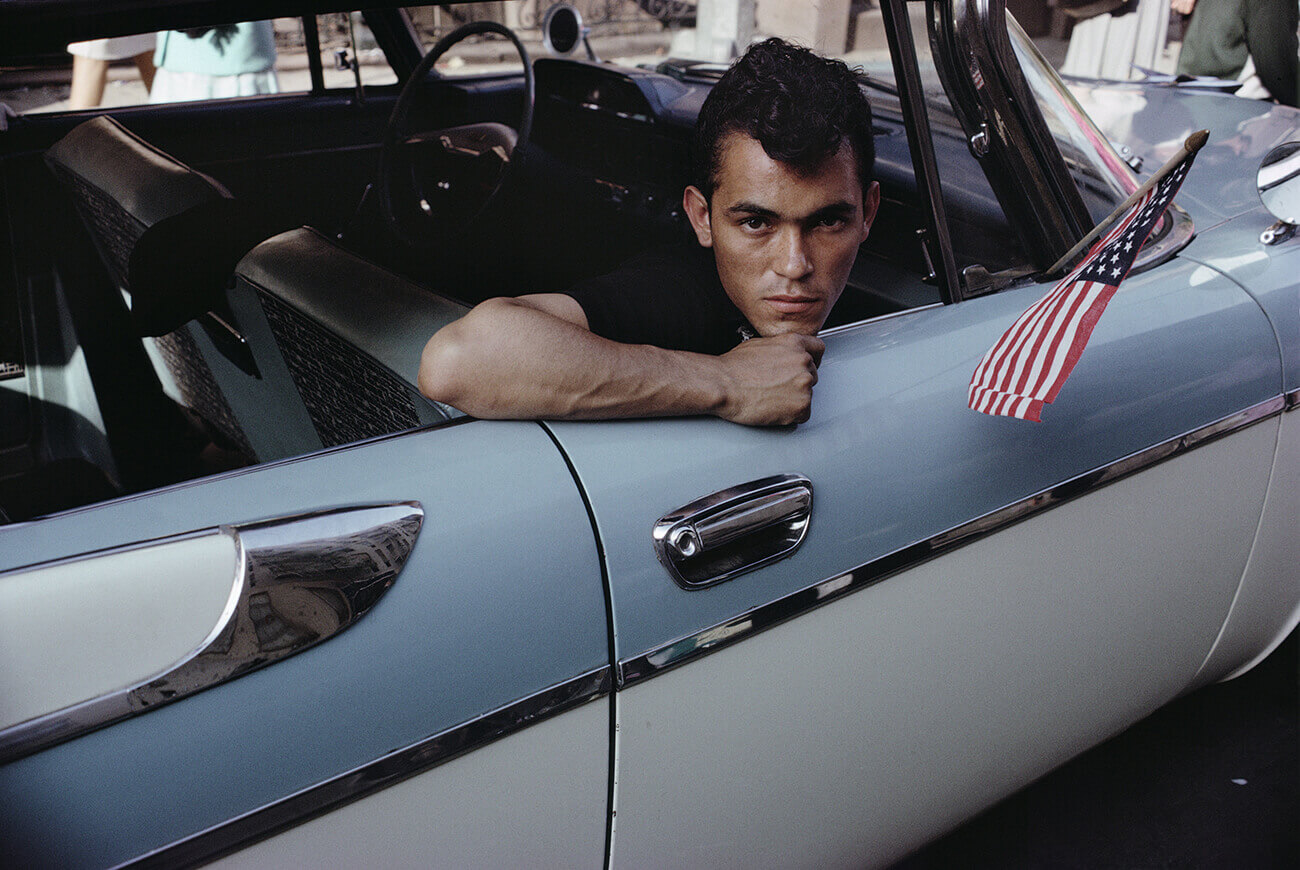

1963, New York City © Joel Meyerowitz, Courtesy Galerie Polka – Paris

“For us (Europeans), a city means above all the past, for the Americans a city is mainly

future; what they love in it is all that it may yet be.” That is what Jean-Paul Sartre had to

say about the American city in the mid-20th century. With their distinctive and instantly

recognisable urban grammar, those cities of the future hold a significant place in our

collective unconscious, symbolising Western progress, the consumer society and the

American dream.

Born in the world’s most iconic city, New Yorker Joel Meyerowitz is a pioneer of what we

call “street photography”. He studied painting then embarked on a photography career

in the 1960s. Inspired by another giant of American photography, Robert Frank, he

produced his first series in black and white. However, he went on to become a pioneer

of colour film, which he finally adopted in 1976 because, as he is fond of saying, “life

is in colour”. This choice set him apart from many other artists who shunned this new

photographic style, but it ultimately contributed to the success of his work.

This exhibition goes beyond a mere retrospective and instead embarks viewers on a

journey through the transformation and diversification of the American cities that he

has passed through over the years. From the tranquil evening vibe of a roadside diner

sign to the chaotic energy of a New York intersection at rush hour, via the splendour

of a Florida swimming pool… each image contributes to a stunning fresco that reveals

the soul of a nation and its people. Joel Meyerowitz observes, frames, playfully brings

out the detail, and transforms the ordinary into something extraordinary. A journey

along linear streets where the light dances on the façades of the buildings, that soar

skywards. And where passers-by become unwilling extras in this magnificent movie

entitled America.

All About Joel Meyerowitz

Four-year-old Andy Anderson and his Jack Russell, Tinkerbell, watch as his father, Andrew Anderson, and other ranch-hands spread hay along the pasture for the grass-fed cattle on their ranch in Twin Bridges, Montana. © Louise Johns 2017

Montana is big sky country, as the vehicle licence plates in this iconic state of the

American West will tell you. The region’s vast wild expanses, often associated with the

American pioneer spirit, are a symbol of freedom and adventure.

Montana is also the home of photographer Louise Johns, who settled in the heart of the

countryside here after extensive travelling. She tells the story of efforts to restore bison

populations on the plains in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem – an area of 90,000

square kilometres stretching from northern Wyoming through Idaho to southern

Montana. With the reintroduction of bison, along with wolves and grizzly bears, farming

communities are grappling with some major challenges. They are committed to the

sustainable management of these lands and seek ways of sustaining their livelihood

while preserving wildlife – and adapting to the growing pressures of development,

tourism and leisure. From another perspective, the recovery of the bison is crucial

to the cultural affirmation of the Amerindian tribes, who have had a life-sustaining

relationship with this animal for over 10,000 years.

The bison has thus become a point of contention, pitting livestock ranchers, scientists,

and tribes against one another, in a cultural clash over competing perspectives

and agendas. In 2023, on the edge of Glacier National Park, the Blackfeet Nation

became the first indigenous community to release wild bison on their ancestral lands.

These complex issues are documented by Louise Johns, in photographs that are an

ode to the Wild West, to a way of life passed down from the cowboys of yesteryear.

Her images also provide valuable insights into the complicated and conflict-ridden

relationships between the various groups living in this fabled territory.

www.louisejohnsphoto.com

© Alessandro Cinque/Prix Photo Terre Solidaire

Presented here to the public for the first time, this sensitive and committed exhibition

is the culmination of several years’ work and trips to four Latin American countries.

This incredible journey was made possible thanks to the generous support of the

Terre Solidaire Photo Prize for humanist and environmental photography, awarded

by CCFD-Terre Solidaire. The images chronicle the complex coexistence between

the mining industry and the indigenous communities of the Andean territories.

It is an ambitious project by documentary photographer Alessandro Cinque (who lives

in Lima), begun seven years ago in Peru, the world’s second-largest producer of copper

and silver. Mining contributes twice as much to the Peruvian economy as tourism.

But for the Andean communities, it plunders their wealth and their water sources,

the lifeblood of their economy. Just a few kilometres from the Peruvian border are

the two colossal undertakings that launched Ecuador’s large-scale mining operations.

Among them is Mirador, the project that sparked indigenous protests in 2012.

Further south, in Argentina, civil resistance has managed to delay two mining projects in

the town of Andalgalá. Since 2010, not a Saturday goes by without local communities

taking to the streets in protest. Last December, Bolivia inaugurated its first industrial-

scale lithium plant in the Uyuni salt flats. Yet just three hours away, dozens of miners

die every year searching for silver ore in the town of Potosí.

Peru, Ecuador, Argentina and Bolivia share a similar history of large-scale mining.

In the style of the great Amerindian photographer Martín Chambi, using soft, low-

contrast images that do not add drama to drama, this exhibition reveals the constant

struggle between economic growth, the preservation of traditional ways of life, the

safeguarding of natural areas and the dramatic consequences on the population’s

health.

www.louisejohnsphoto.com

GEORGE STEINMETZ: Feed the Planet (United States b. 1957)

Where does your food come from? The rib steak, the chicken leg, the carrots and what

about that innocent lettuce? Do you know how these foods end up on your plate? So

many people in the West look no further than their supermarket aisles. And they often

have no idea how the food is produced or where it comes from.

This exhibition, and the book it is based on, attempt to give a comprehensive answer

to this question. Feed the Planet is the outcome of ten years’ work in the field, in

40 countries, across five oceans and on every continent on our planet.

An unprecedented project meticulously undertaken by photojournalist George

Steinmetz, known the world over for the quality of his aerial images and the precision

of his shots; an extraordinary visual document illustrating the global food system relied

on to feed the 8 billion people who live on our planet.

Beyond the demographics, there are many questions. Since the domestication of

plants began around 11,000 years ago, humans have converted 40% of the Earth’s

land mass into farmland – often to the detriment of biodiversity. In the oceans, more

than half the fish biomass has disappeared since the 1950s. And we cannot overlook

the fact that today’s agricultural systems account for 30% of global greenhouse gas

emissions.

How do we accommodate these systems with the prospect of 2 billion more people

on Earth by 2050? How can they be adapted to cope with rising protein consumption

in emerging countries? If the world’s food supply needs to double in the next 30 years,

how will this be achieved this without wiping out the few remaining wild spaces and

creatures? Let’s never forget that, as consumers with the power to vote with our forks,

it is our duty to ensure the fair utilisation of our resources. And that on a large scale, the

decisions we all take can have a significant impact on market supply. And, ultimately,

on the environment.

www.georgesteinmetz.com

MITCH DOBROWNER: In the Eyes of the Storm (United States b. 1956)

When we see a tornado, our reflex is to run for cover. Or to lock ourselves in our cellar.

No so for Mitch Dobrowner, who heads straight for the storm. Where his fellow wildlife

photographers track birds and mammals, he hunts down vortexes, storm supercells

and other severe weather phenomena. “They take on so many different aspects, faces

and personalities; I’m in awe watching them,” explains the photographer who first

started taking pictures as a teenager, but later set his camera aside until 2005 while

he raised his family. “It’s watching Mother Nature at her finest. My only hope is that my

images do justice to these amazing phenomena of nature.”

It’s a passion that comes with an element of danger. Dobrowner is aware of the

risks involved, but chooses to get as close as he can to the vortexes to further his

understanding of these phenomena. In 2010, in Wyoming, he got caught in a hailstorm.

“We were being chased by the storm – instead of us chasing after it.” The incident

didn’t discourage him, as he has continued to track down the nastiest storms and

weather conditions for almost two decades. “My job is to get to the right place at the

right time, then let nature show itself,” he says. He has even been honoured by Google

for his use of their technology in his weather quests.

His systematic use of black and white to accentuate the harshness of the storms

stems from his admiration for Ansel Adams – another master of American landscape

photography. An approach that won him the Iris d’Or at the Sony World Photography

Awards in 2012. Despite his success and the esteem he has gained, Mitch Dobrowner

refuses to be labelled a “storm chaser”: “I don’t like to put things in boxes. I’m just a

landscape photographer.”

Alll About Mitch Dobrowner

ALICE PALLOT: The Perils of Nature (France b. 1995)

This year’s winner of the Leica Award for New Takes on Environmental Photography,

introduced by the La Gacilly Photo Festival is a raw talent, a sensitive artist, concerned

with clinical truth. As soon as she embarked on a course at the École nationale supérieure

des arts visuels de La Cambre (ENSAV) in Brussels, Alice Pallot began exploring

the complex relationship between humans and their constantly changing environment,

raising questions that are inherently relevant to our times. In her visual experiments, she

tends to reveal hidden realities by opening the doors of her imagination.

“Through [my images], I explore the influence of man and science on nature and the

links that develop between them,” she explains. “I use this to create fictional universes,

often through narration. I’m infusing new life into nature that’s dying out. When on my

travels, I play with the natural elements that surround me. My approach is similar to

that of a researcher: I document, explore, research and then go out into the field to

develop my project. Applying a cold, phantasmagorical aesthetic, I draw the viewer

into a parallel universe inspired by reality.”

The fruits of her reflections are powerfully apparent in her latest series, Algues Maudites.

It brings to light and condemns the alarming spread of green algae on Brittany’s

coasts. Attributed to high levels of nitrates and phosphates, the algae proliferate

along the coastline and release toxins when they decay. In extreme concentration, this

phenomenon leads to oxygen depletion, ecosystem imbalance and biodiversity loss.

Similarly, in her Oasis series, the photographer reveals the absurdity of a cut flower

market that celebrates beauty but causes unsuspected pollution.

Capturing the invisible in an often futuristic aesthetic and working with an unconventional

colour palette, as though applying filters to our much-abused nature, Pallot’s works are

a reminder of the fragility and unpredictability of our world, continually tested by human

action.

alicepallot.com

© Ulla Lohmann pour la Fondation Yves Rocher

Ten years ago, the province of East New Britain in Papua New Guinea was heavily

forested. Over 98% of its primary forest was still intact. Now, however, increased

logging – to clear land for oil palm plantations – has exacerbated the loss of forest cover.

Before 2008, the area lost each year was around 3,600 hectares. But deforestation

has increased exponentially over the last 20 years. Nearly 20,000 hectares are now

sacrificed every year. In all, it is estimated that New Britain lost 10% of its tree cover

between 2001 and 2020 – nearly 60% of which is considered to be primary forest.

Photographer Ulla Lohmann is well with New Britain, so named because the island

was discovered in 1700 by British explorer William Dampier. She first went there in

2001, on her first trip to the region, and immediately fell in love with the landscapes,

the volcanoes that dot the land, the people (Austronesians and Papuans) and the

traditional cultures that subsist there. As part of a photographic commission from the

Yves Rocher Foundation on the final sanctuaries of biodiversity, she returned there

to document the upheavals weakening its ecosystem and endangering an ancestral

way of life. “The diversity of life is evident everywhere you look, both on land, in

the primary forests teeming with as yet unknown species, and underwater, with

some of the richest coral reefs on the planet,” explains the German photographer.

The exhibition takes us on a thrilling adventure into the Nakanai mountains and to the

majestic volcanoes of the Bismarck archipelago, offering a taste of far-off lands, worlds

away from Brittany or Britain. Yet, the themes of nature preservation and environmental

safeguarding are just as relevant there as they are in our regions.

ullalohmann.com

GAËL TURINE: The Spirits of the Forest (Belgium b. 1972)

Welcome to Benin, former kingdom of Dahomey and cradle of voodoo. In this territory

found to the north of the Gulf of Guinea, wedged between Togo to the west and

Nigeria to the east, the boundary between the living and the dead is more tenuous than

the non-believer might assume.

So, what exactly is voodoo? A religion, just like Christianity and Islam – both of which

are highly developed in the region. Its practitioners worship a pantheon of gods and

minor deities who inhabit natural elements such as a stone, a waterfall… or a tree. It took

time, patience and the authorisation of the country’s spiritual leaders for Gaël Turine, a

sensitive social reporter, to gain access to the sacred forests of Mitogbodji, Fâ-Zoun

and Houinyèhouévé: closed quarters, places of worship off-limits to the uninitiated.

Here, the deity is aware of your presence, but remains unseen: it allows mortals to live

and prosper, but lives hidden away. And it is thanks to traditional knowledge, taboos

and totems, tales and legends handed down the generations, that these forests have

remained protected from human activity.

However, these now represent only 0.2% of the territory and are threatened by

demographic pressure, the expansion of farmland and the rise of evangelical churches.

Between 2005 and 2015, Benin’s total forest area shrank by more than 20%, with an

ongoing deforestation rate of more than 2% per year according to the World Bank.

Gaël Turine set out to understand and document this complex situation, focusing

on the survival of these rituals intricately tied to the existence of a preserved natural

environment. Should it disappear, should these sources of life become contaminated,

a whole system of beliefs and a complete culture will be lost forever.

www.gaelturine.com

BERNARD PLOSSU: Fresson Colours (France b. 1945)

Bernard Plossu likes to call himself “half-traveller and half-migratory photographer”, but

he really needs no introduction. For years, he has been roaming the world, capturing furtive

moments in Mexico’s Chiapas, the American West, the Niger desert, the villages of Morocco

and on the coast of Brittany. He became famous for his black-and-whites, imbued with

iridescent grey. Too often compared to Robert Frank or Édouard Boubat, both of whom

he admires, his style is singular and deeply sensitive. His eyes are as sharp as his memory.

When we arrived at his home in La Ciotat, he chuckled about the sedentary lifestyle

that has him tied to this building, because his lifelong pursuit of the meaning of life

always revolved around travel. With his youthful good looks and tender smile, he took

us on a tour of this house of memories where, from floor to ceiling, there are piles of

jumbled boxes of negatives, prints of all kinds, old books, drawings donated by his

painter friends and objects unearthed over sixty years of wanderlust. “It’s an organised

mess,” he explains, “I’m the only one who can locate my little ones.” He wanted to

show us a photograph taken in Mexico in 1965. “It’s like a painting!” we exclaimed.

An unfortunate compliment. That’s the very thing he dislikes hearing, even though he

admits to an affinity with Corot for his lighting, Courbet for his landscapes, Malevitch

for his geometric forms and Hopper for his abstract forms.

Right from his earliest photographs, Bernard Plossu invented a visual grammar that

combines subjectivity, simplicity, a sensorial dimension and rigorous composition.

Here, it is his lesser-known colour photographs that we wanted to showcase with

these Fresson prints. The Fresson pigment process was invented in the 19th century

by the family of the same name in Savigny-sur-Orge, south of Paris. The special texture

and subtle rendering it gives is the perfect match for the no-frills approach adopted

by the photographer, who seeks to distance himself from the spectacular and the

grandiloquent. What emerges are images of poetry, the kind that sets the world, and

its many forms, aflutter. With a powdery, slightly charcoaly finish that gives landscapes

an unreal look.

SOPHIE ZÉNON:The Memories of Stones, Discovering sensitive rural heritage in Morbihan (France b. 1965)

Leave the major tourist attractions of Morbihan behind for a while, and set off

on the back roads, venture into the Breton moors, follow the coastal paths and

get lost in the remote hamlets. You’ll discover a host of hidden treasures built,

sculpted and fashioned, sometimes in ancient times. They bear witness to the

multitude of activities found here in bygone eras, but are also the seeds of a culture

bequeathed to us by our ancestors. You’ll find a chapel with chiselled tympanums,

further along a washhouse carved into a hollow, then a crumbling manor house or

an imposing granite calvary. Carry on and you’ll come to a megalithic site with

endless alignments, like those that astounded Stendhal, who described an ancient

procession of stones basking in the atmosphere conjured up by the dark sea…

Over the course of a winter, from Locuan to Locmaria, from l’Île d’Arz to Guehenno,

visual artist Sophie Zénon travelled the length and breadth of Morbihan, accompanied

by Diego Mens, heritage curator at the département’s council, the initiator of this new

photographic commission. So what marked her most? ‘This fusion of granite with the

landscape, and with plants in particular. It gives off an atmosphere that is at times

serene, at times melancholy, conducive to a form of introspection and meditation.”

This explains the unconventional approach used to capture the shots, as dictated

by the artist. She is relentless in her quest to experiment with the photographic

medium, which gives rise to organic, vibrant and poetic works. Here, she opted for

a series of frontal shots and long shots. She used an old technique, the orotone, a

photographic print on a silver gelatine glass plate to which she applied gold tone

with a brush. The beholder is treated to a precious, delicate and fragile artefact,

imbued with a timeless quality and adorned in shades of black and tan echoing

the sacred monuments that hold such significance for the region’s inhabitants.

In the green labyrinth at La Gacilly, the photographs, printed in large format on brushed

aluminium, shimmer and play with light and shadow, creating a surprising effect of

depth.

www.sophiezenon.com