Yesterday I met with

Takeshi Moro. It was a different day and it wasn't just the rain in the midst of the drought in California. I've looked at Takeshi's work before: large color photographs of Finnish saunas, actually three unfolding stories of Finnish saunas with a black and white chapter in the middle.

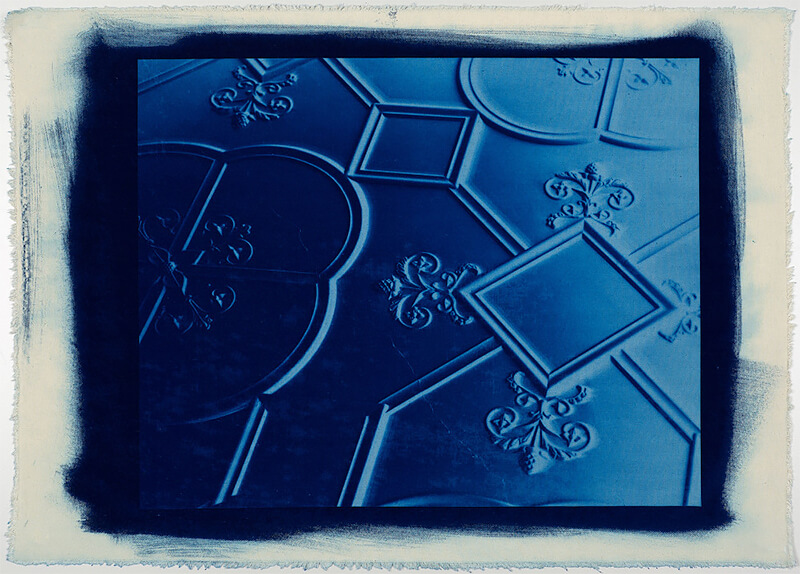

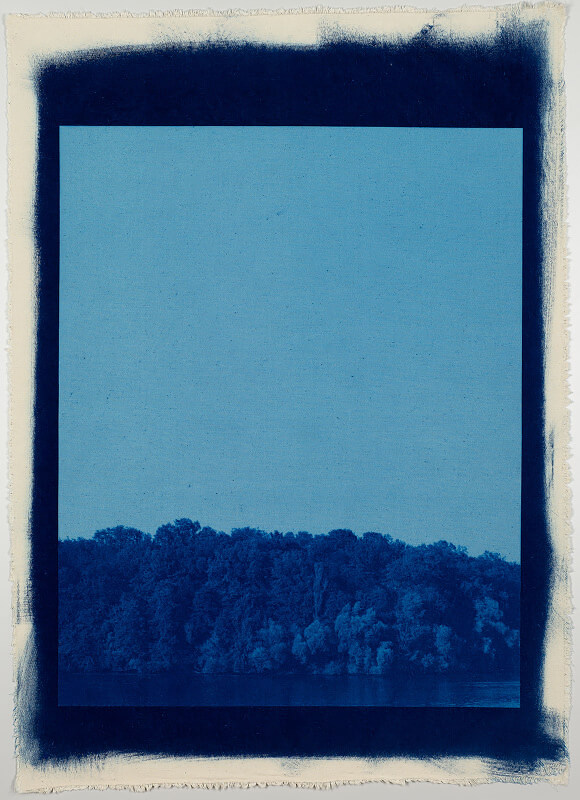

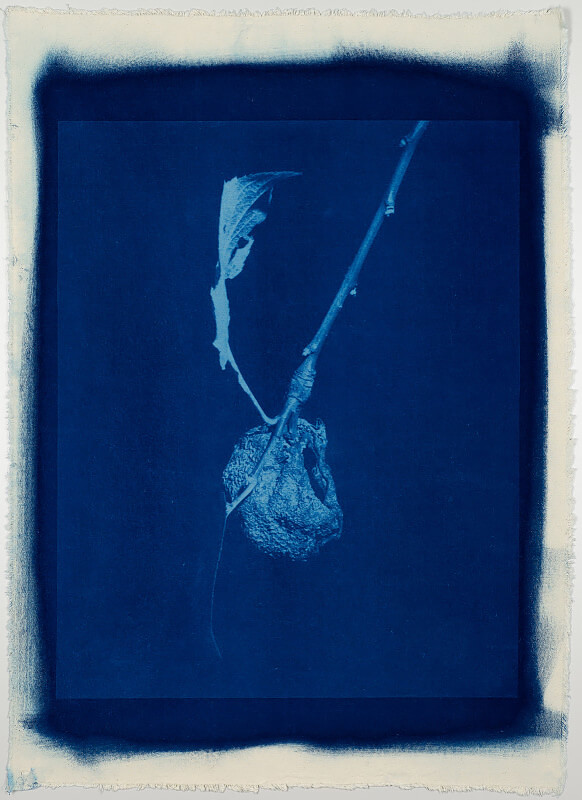

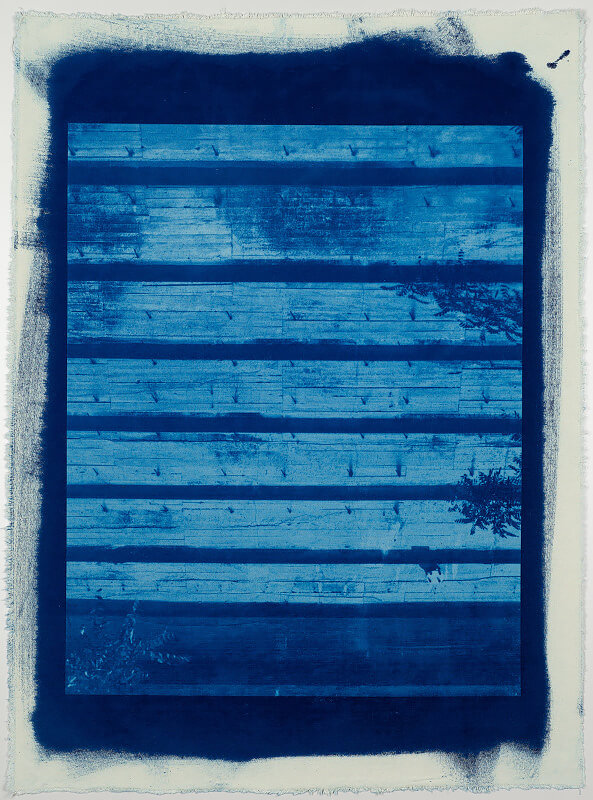

That's something else though. This time, the photographer opened a giant box and unveiled something I had never seen before: cyanotypes on large canvases. Now, I know what you're thinking: canvas? Blasphemy. (That's usually how I react to canvas anyway). But these prints were gorgeous continuous tone cyanotypes of the richest blue, with all the mid-tones on soft, not quite limp, large canvases with slightly frayed edges like jeans that have been washed too much. As he picked them up and turned them and laid them down again, they just seemed perfect. Canvas? How could it be? Well, there was a lot of technical explaining to do including a lot of geeking out over a process invented in 1842 and the discussion of a new cyanotype process recently developed by Mike Ware... and then not learning how Takeshi had changed it (never give away your secrets), but knowing that he had to amend the formula and then seeing the results of his experimentation. As a historical process nerd, I was intrigued and impressed to say the least.

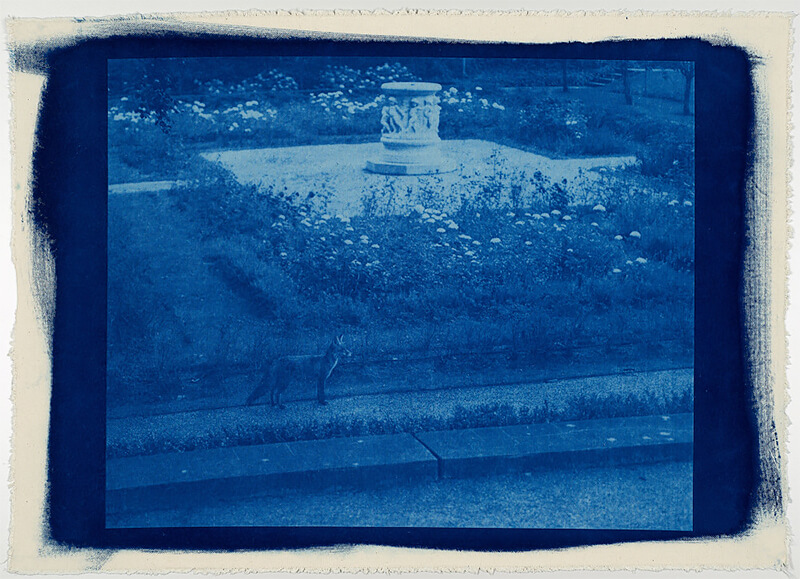

But here is the important part, really. Beyond the beautiful prints and the stunning images, it's the story behind Takeshi's series, Wannsee in Berliner Blau that shakes the viewer to the core. There was a lot I didn't know about Wannsee, Germany, but now with these eerily quiet pictures, Takeshi Moro has told a story so unsettling, that I won't easily forget what happened in this place:

For the past four years, I have been photographing the landscape and historic buildings in Wannsee, Germany. It is a suburban town, situated 15 miles southwest of Berlin. The town is essentially an island, with water (a river or a lake) surrounding the area. The town's name was made infamous by the Wannsee Conference - the site where Nazi leaders met to institutionalize the Holocaust. 'The Little White House' is on the other side of the river from Wannsee. Scholars contend that it was in this house that President Harry S. Truman ordered the use of the atomic bomb on Japan.

The confluence of these landmark events is not entirely an accident. Historically, the upper echelons of Berlin society occupied the suburban lakefront properties. It was a comfortable retreat from Berlin and on the way to the royal palaces in Potsdam. The Nazis eventually occupied many of the buildings, but Wannsee escaped Allied bombing campaigns due to its suburban location. Understandably, on the island and within the surrounding areas are the sites of numerous events related to Nazi Germany and to the Cold War era.

I hope to address how the suburban landscape and the architecture affected the decisions that shaped the world at the time. In addition, I am intrigued by the spirit that perhaps continues to exist at these sites. The walls, the ceilings, the furniture, the artworks that were present during the meetings (confirmed via research at archives of Wannsee and Truman libraries). Obviously, they can't talk but can they play a role in bearing witness to these events? The stark contrast between the serenity and horror that surround this island speaks to the predicament of our memory — the weight of history is so easily masked, and yet indelible.

One of the sites that I have paid particular attention to is the orchard of Haus der Wannsee Konferenz. It is a beautifully maintained orchard with a bountiful harvest of apples, pears, and plums. Most are not aware that Jewish forced laborers maintained the garden during the Nazi occupation, including during the Conference. And after the war, the original orchard was removed to make way for a helicopter- landing pad, in anticipation of an Israeli premier's visit —his visit was eventually cancelled. Since then, the orchard has been restored and exists today as a peaceful bucolic landscape. This history was revealed after interviewing the researchers at Haus der Wannsee Konferenz and is not public knowledge.

The photographs are printed on cotton canvas with a newly formulated cyanotype processing. I decided to utilize the blue and white of the Prussian blue (also known as Berlin blue – Berliner blau) as the color was invented in Berlin in the 18th century. I am devising my own chemical formula (based on Mike Ware) at a chemistry lab at Santa Clara University. The new formula is more difficult to formulate, but improves the tonal range of the photographs compared to Sir John Herschel's invention in 1842. I am continuing to research new methods to improve the tonal range and consistency of the prints.

Takeshi Moro left me a bit speechless after our meeting. After looking at all the images of places where people's fates were decided, the silence of these pictures has given way to a roar.

These images were recently on view at Gallery Possum in Berlin, Germany, and Büro für kulturelle Übersetzungen in Leipzig, Germany, as well as at Gallery 100 Percent in San Francisco, California.

Biography

Takeshi Moro was born in Fukaya, Japan and spent most of his childhood in the UK. Moro attended Brown University, where he double majored in Economics and Visual Arts, while also taking photography courses at the Rhode Island School of Design. He worked in the fields of corporate finance and marketing/design before receiving his M.F.A. from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He is currently an Assistant Professor at Santa Clara University. He is the founder and director of tmoro projects, a 501(c)(3) non-profit community art space in Silicon Valley. He has participated in fellowships and residencies in Finland, Germany, Iceland, Japan, and South Korea. Moro's work has been exhibited internationally, including a solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago and Serlachius Museot, Finland.