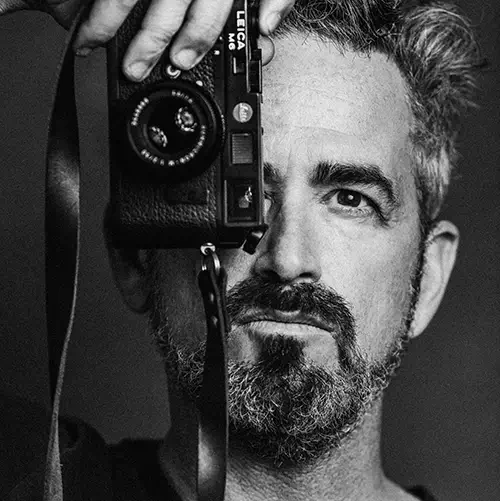

Josh S. Rose is a multidisciplinary artist working across photography, film, and writing. His practice bridges visual and performing arts, with a strong focus on movement, emotion, and the expressive potential of the image.

Known for his long-standing collaborations with leading dance companies and performers, Rose brings together authenticity and precise composition—a balance he describes as “technical romanticism.” His work has been commissioned and exhibited internationally, appearing in outlets such as Vogue, at the Super Bowl, in film festivals, and most recently as a large-scale installation for Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts.

A sought-after collaborator, he has worked with major artists, cultural institutions, and brands, following a previous career as Chief Creative Officer at Interpublic Group and the founder of Humans Are Social.

We asked him a few questions about his life and work.

All About Photo: How has your journey as an artist evolved into the practice you have now?

Josh S. Rose: I had been doing a lot of random series as an artist-photographer. I’m not sure there was a throughline to any of it, just whatever came to me. Within that set of concepts there was this one idea I called “Conversations With Walls,” where I had actors or friends pretend to talk, interact, plead, or argue with a wall. One day, one of the actors suggested I work with a dancer. He introduced me to someone and it was in that session that I saw how incredible it is to work with an artist who can express emotion through movement. I started working with dancers more and more and the feedback was very positive from it, and I pushed in. The timing was good for what I was doing.

My style of photography, which tends to have more inclusion of environment, I think coincided well with what was happening in dance. Dance has been evolving over the last decade, where it has left the world of theater and truly entered into live space. But even outside, most photographers were still shooting dance as though the dancers were in a studio or on stage. My way of working is to let movement feel alive within the reality of the environment and that just naturally fits with what a number of artistic directors and choreographers were doing.

I had an artist residency with the Los Angeles Dance Project, under Benjamin Millepied, and another residency with California Institute of the Arts, under Dimitri Chamblas. And then another within the fine arts division of United Talent Agency (UTA). The opportunities came quickly once I found my voice. Within these relationships, I think I honed in on what I really wanted to accomplish as a photographer. My joy is in the community more than finding wall space. This cohort of people who love to get out there and make art together is growing. We meet up in these intimate, inventive and private little settings: art openings, private events and within the playground of other projects. Someone will be shooting a music video, or doing an art install, or documenting a small combination dance sequence, and I’ll get invited to just come play around and create on top of it. It’s very organic and unlabeled, but also feels very substantial at the same time. I enjoy being in this space that is not already formalized and institutionalized.

LA Dance Project © Josh S. Rose

LA Dance Project © Josh S. Rose

I’d say nearly everything I do now is a product of early influences. The environment I grew up in was filled with color. Artists, filmmakers, musicians, drug dealers, psychologists, writers, gamblers, and pornographers. It was Southern California in the 70s and everything felt like a psychotic revolution of the mind.

There was a photograph in our living room growing up by Carl Mydans. A black and white shot called “Fog Coming In, Swansea, England.” It hung over me in more ways than one. My mother had great taste in art and wine, so if she believed in an image, it meant something. That photo shaped my idea of what a picture could hold.

The first time I saw a photograph developed it was at the racetrack. Our track had the first strip camera at any racetrack, but they were probably at a lot of tracks by the 70s when I was hanging out there. With a strip camera, the film moves along with the horses, so they all appear on one strip of film. A race would end and if it was close, the word PHOTO popped up on the board. A runner would rush the film up to the small booth, and I got to hang out there because I was a curious kid and that went a long way back then. The film guy let me hang out as he would develop these photo finish images and then call the result up to the placing judges with 20,000 people waiting on the results. I loved everything about that place. I learned there that developing is a means to an end. That’s not the art. The art is in riding the horse.

My grandfather was a great hobbyist travel photographer. Really quite good. He got me a Nikkormat for my birthday when I was ten. Then a family friend let me use his darkroom. He also taught me guitar. That was how things sort of went. You just ran around and did as much as you could. That’s what I’ve been trying to get back to all these years later.

You’ve described your style as “technical romanticism.” What does that mean to you?

For me it all goes back to the Romantics. I believe in trying to create images that evoke emotion and the way the Romantic artists did that was by capturing people’s responses to their environments. It’s a process and a way of working that involves having and using feelings, emotions, exploration, and employing a good amount of intuition and even a sense of the meaning within the environments or places you are shooting. That’s the romantic part.

There are also choices being made with the various technicalities of using a camera and processing imagery that are inherent in anyone’s work who is doing art with photography. The technical part of “technical romanticism” is about being very intentional with technique and pairing up those techniques with the assignment somehow. There’s a time for abstraction in photography and 20 odd different ways you might do that. Same with more formal compositions and lens choices. To pick and choose these techniques to best convey the emotionality of the scene is part of the process.

Maximalism. CALARTS. Choreography Dimitri Chamblass. Los Angeles, 2025 © Josh S. Rose

Maximalism. CALARTS. Choreography Dimitri Chamblass. Los Angeles, 2025 © Josh S. Rose

Maximalism. CALARTS. Choreography Dimitri Chamblass. Los Angeles, 2025 © Josh S. Rose

I spent a lot of years in advertising, where ideas were formed in pressure cooking boxes, isolated from the world. When I left, I traveled the country photographing blue-collar workers. The thing I kept hearing from people was that happiness had a lot to do with community. That stayed with me.

So when I started working with dancers and other artists, it felt like finding the community I’d been looking for. They welcomed me in. And the work became something we made together, not something I made alone. I like that feeling. Art as a shared thing instead of a spotlight or a transaction. The artists who welcome me into their fold I think do so because I also bring an art to it. It’s not objective documentary. I’m here to make art, too. I just like doing it in the company of other artists, which is how I grew up and how I seem to work best.

What has movement taught you about visual storytelling?

The big learning, I think, when working with movers is the way you have to flow through things both recognizable and abstract. You think you understand what is going on in a choreography, and then you’re like, “Wait, what is that supposed to mean?” You have to be able to play in that space, so it’s not a practice for anyone who needs things to be very linear. Then when you stick with that, the sense of narrative explodes and you can invent inside it to great effect, doing things that are more about expression, mood and emotional territories.

I’ve also learned to be present and deeply focused on the various steps of the creative or narrative process in a way I never knew before. Each element of a work with a dancer is its own art form. I don’t have to think too much about the choreo when we are just talking about concepts, and I don’t think too much about the edit when we are shooting. Being present through each part of the creative process without always needing to know all the answers ahead of time is, in a way, the art of it.

Has working with dancers influenced your sense of rhythm and composition?

For sure. When you first start in with dance, you sort of obsess on the timing of the shot. And it definitely helps to be able to count like a dancer does. You do start to feel the rhythm of a dance and that guides the shutter. However, not all dancers are counters and that’s where it gets really interesting.

Far more influential than the timing of a shot, or capturing the most athletic moment, is trying to figure out where the emotion of an image is going to evolve from. I have learned through dance to compose with emotional relationships more than the graphic elements of a frame. With a dancer, you establish a shared vocabulary that allows you to discuss deeper concepts and then explore them somatically.

For your upcoming, forty-year installation with the Lincoln Center, what story do you hope it carries into the future?

The piece is about space and performance and the way the arts mix into the city. A lot of people will be seeing it. If it gives someone a sense that the arts and the city belong to each other, then the work has done its job.

My relationship to New York goes way back to childhood. I spent a summer there when I was a teenager. I met Keith Haring at his Pop Shop, and I stumbled into underground parties with performance art being just sort of a normal thing. You’d go into a bar and the Ramones would be hanging out. This is the New York I continued to chase, visit and admire for years. I wanted to create a piece that felt born of that interconnected art-life ethos but carried through into the now.

One of my favorite things about the Lincoln Center is that if you stand in the middle of the space, you’ll see everyone who works there at some point. Musicians carrying their instruments, just off the train. Ballet dancers walking in small flocks. Performers hanging out among the visitors. That, to me, is the magic of that organization and something you don’t see very many places in the world. It’s special.

Is there a moment or image that captures the “poetry of authenticity” in your work?

I am in process with a dancer that involves capturing her interacting with a block of ice hanging from the ceiling. The ice takes hours to melt, so she has time to react to it in all kinds of ways. Cold, wetness, boredom, surprise, whatever comes up for her. We talked a lot about my place in the piece too, not standing aside documenting, but part of it. Her movement with me, toward me, around me, shapes the image. That’s a new role for a cameraperson.

The ice became another collaborator. A piece of nature with its own timing and attitude. The honesty comes from letting all of these elements be in the beaker and interact without trying to control it. The presence of nature and humans in motion with each other is an extremely beautiful kind of poetry to me and feels at the center of where I am going with this art form.

Shooting in different environments, how does place shape your creative decisions?

Place is part of everything I do. In a lot of photography, the power comes from the contrast between a person and the world around them. But with dancers, it’s more like the body is answering the place.

I have this image with mover Nic Walton where he is upside down with his head in the shallow water of the ocean. That image evolved with our acceptance of the environment and experimenting with various narratives that included it. The place always has a voice.

But at a fundamental level, place and situation are in fact the subject. How we decide to portray the human plight within the somatic response to that environmental situation is where the artistry is felt for me.

Jacob Jonas © Josh S. Rose

My practice is built entirely on staying inspired. If I weren’t inspired, I would happily just sell everything I’ve acquired over the years and go live out my days in Nova Scotia, like Robert Frank. But I am still deeply inspired by the creativity of other people. Curious and mesmerized by it. If I see a movement language that makes me feel something, I run toward it, like a painter discovering a new color. But also it’s inspiring to me that my style of co-creation is as relevant as it is right now. We are seeing a number of film festivals dedicated to dance, for example. Dance programs within art schools are flourishing. The practice just feels very alive right now and so that creates its own energy. I feel pulled by something larger than myself. That’s a very exciting feeling.

Any dream projects or collaborations you’re excited to pursue?

I have this ongoing relationship with the Los Angeles Dance Project and Benjamin Millepied. A few years back, we all set off for Qatar while the World Cup was there and a number of choreographers and dancers did site-specific works among these enormous public artworks by people like Olafur Eliasson and Richard Serra. Being in that desert with dancers and musicians felt like a creative frontier to me and I’ve been in pursuit of something equally outrageous for the next big adventure.

The crossover element between that work in Qatar and this more recent project with Lincoln Center is that both incorporate innovative spaces to play and create in. And as I talked about, new spaces are opportunities for new site-specific responses to go make. I love doing work in unavoidable ways, and having people stop and feel something. That’s the mark I’m always looking to make. I’m interested in projects that play with space and bring aliveness, beauty and emotional resonance into them.

Maximalism. CALARTS. Choreography Dimitri Chamblass. Los Angeles, 2025 © Josh S. Rose

Maximalism. CALARTS. Choreography Dimitri Chamblass. Los Angeles, 2025 © Josh S. Rose

The Passenger. With Marco and Delisa. Los Angeles, Jul 2023 © Josh S. Rose