Janet Delaney has always been drawn to the ways work shapes people’s lives, families, and communities. In her latest book, she turns her lens closer to home, retracing a week she spent in 1980 with her father, a beauty salesman on the verge of retirement. What began as a daughter’s curiosity became a vivid portrait of long days on the road, endless conversations, and the quiet determination behind a lifetime of providing for others.

Through humor, candor, and empathy, Delaney’s photographs reveal not just the hustle of a salesman, but also the love that fueled it. To learn more about this project and her reflections on it, we asked her a few questions.

All About Photo: Too Many Products, Too Much Pressure! began as a two-projector slideshow with audio. What motivated you to tell this story in that original format, and what did that medium allow you to express that still photography alone might not?

Janet Delaney: By having the images dissolve into one another and by incorporating language and ambient sound, I was able to create a hybrid format that was very filmic. The story unfolds as the photographs slide by. When the piece was show in a dark auditorium there was an immersive quality that I really enjoyed. Everyone seeing the work at the same time was exciting and encouraged dialog.

How did your perspective on your father's work—and labor more broadly—shift during the process of documenting his daily routine for this project?

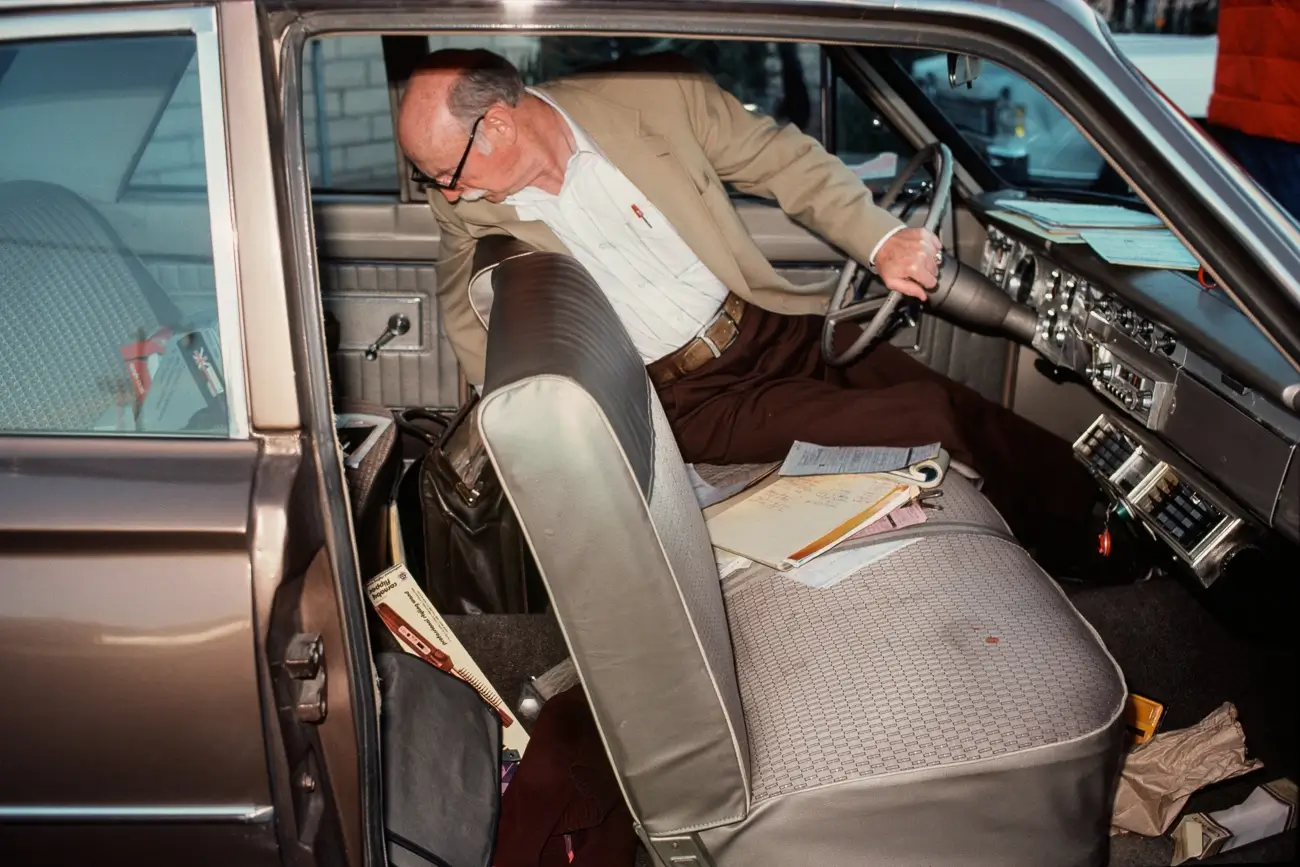

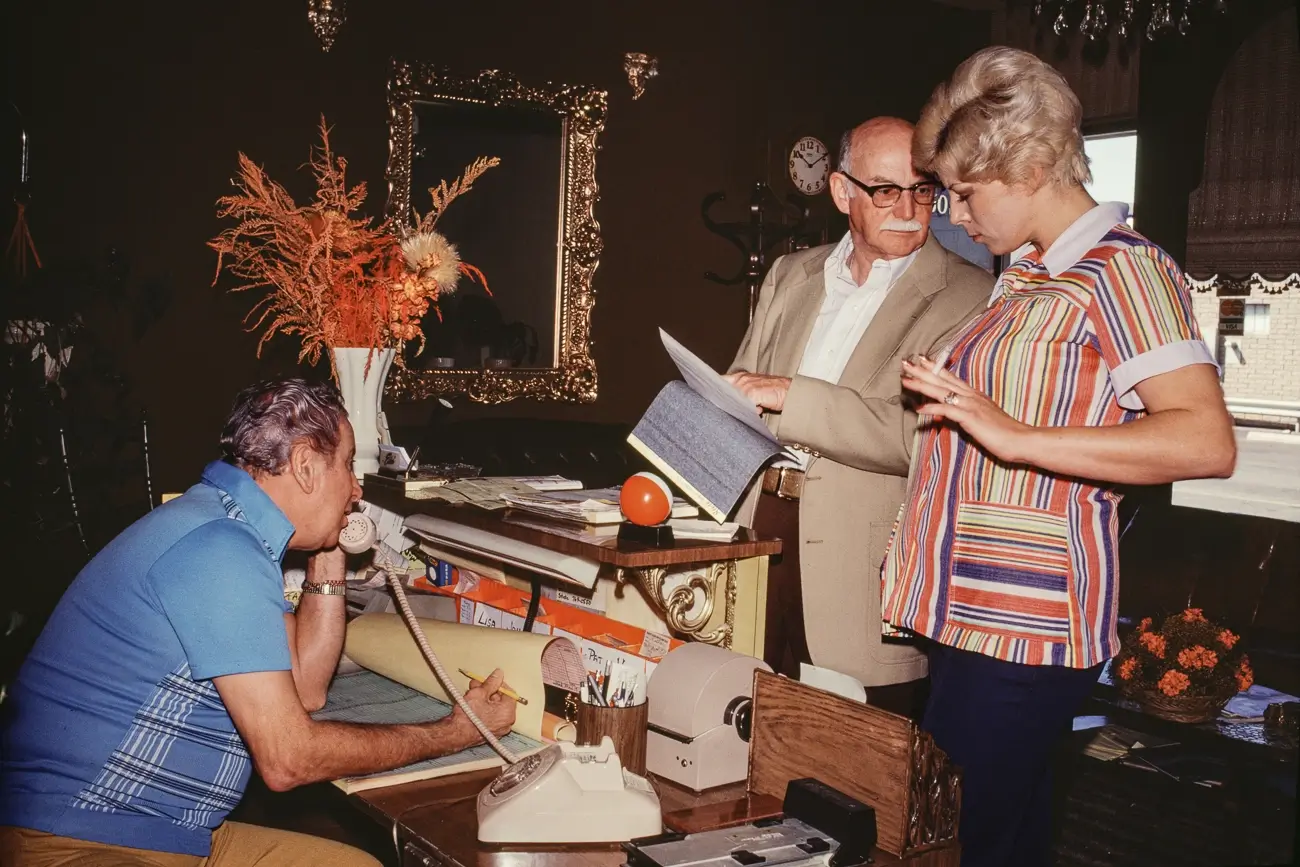

I knew my father worked hard, but I had no idea just how much energy it took to do his job. When I went to work with him, he was 65 and I was 27; I could barely keep up. Though I had grown up with elements of his work strewn about our home – invoices on the kitchen table, permanent waves on the backseat of the car, phone orders coming in at all hours – I had not really understood the actual act of selling that was so crucial to his success. The emotional relationships he had with the hairdressers were essential to building trust and loyalty. But beyond all the friendly happy talk there was a deep layer of frustrating detail that he had to navigate in order to make the sale complete. Even though my rebellious anti-beauty second wave feminism was offended by all the “products”, I came away with a great deal of respect for his efforts.

Work was a part of every day at our house. There was never any clear time off except for the two -week car trips we took in August. And of course Christmas Day. I think that really shaped my own life as a freelance photographer, an artist, a teacher. I have always had my studio in my home. I married a general contractor, and he had his office in our house for the first 15 years while we raised our daughters. We’d put the girls to bed and go back to work. The thing is, we liked what we did so it was not so bad, that was the key to it. Yes, stressful, but also very exciting to create our own lives this way.

The project blends humor, flash, and frontal composition to explore beauty parlors—spaces loaded with social codes and gender expectations. How did you navigate your own conflicting feelings about these places, having grown up during an era of cultural rebellion against consumerism and gender norms?

By the time I dropped back into my dad’s world I had a fairly strong sense of self. Those early conflicts with my dad about women’s rights, had dissipated a bit. And as the larger culture was shifting in the 1970s he was beginning to understand my point of view. Also my opinion softened as I saw the strength in the women who owned their businesses. While I never embraced “Girl Culture” I definitely acknowledged the camaraderie that came with time spent in the salons.

Your images seem to oscillate between a warm familial intimacy and a cool observational distance. Was this duality something you were consciously trying to achieve?

I don’t think I am that predictive in my practice. Once I show up to photograph, I am working more from the heart than the head. Perhaps the editing process creates the oscillation you see. I know I gravitate to a more distanced and organized perspective in general. The frame of the photograph can create a stage where the action unfolds. I had easy access to my dad, so the warm was readily available.

The Evening Hug © Janet Delaney

I love that you feel there is humor in my work. Again, this is not something that I consciously aim for, but I definitely embrace it when it happens. It’s the magic sauce of a good image.

This was your first MFA project in 1980, and now, decades later, it's being revisited as a monograph. What was it like to return to this body of work after so much time had passed?

I have always loved this project because making it created such a beautiful bond with my dad. When he disappeared into a fog of dementia, I was so glad I had this piece of him that I could still hold onto. I made a book dummy in 2014, but nothing came of it. When the publishers Clint and Alex Woodside, came to my studio I showed it to them because it seemed like it was important as a piece that foreshadowed my work that followed: the South of Market book, the work in Nicaragua and in the most recent series, SoMa Now. In all these projects I am telling the personal story of how people live and work using their voices to shape the content.

In revisiting this project, what surprised you most—either in the images themselves or in how you now relate to your younger self who made them?

I had not thought about this work in much detail after I finished it. I moved on to other projects, but now looking back I am surprised to see how foundational this work was to all the work that followed. Too Many Products was my first effort at a new form of documentary photography that was not trying to be objective, that included my own voice and that offered the personal story as a way into larger social-political dialogs.

Do you think the labor you documented in 1980—rooted in face-to-face interactions and tangible products—has something vital to say to younger generations navigating digital and often invisible forms of work?

We can’t go back to some idealized past but it would be helpful to acknowledge what we have lost as we have gained so much efficiency through the use of online interactions. The shop local movement is certainly an immediate response and one I embrace. It takes some effort but without it we lose our shared public space and all that it offers. In the early Oughts people responded to wave of tech washing into their lives by returning to more handmade, locally sourced lifestyle, but this too can be commodified.

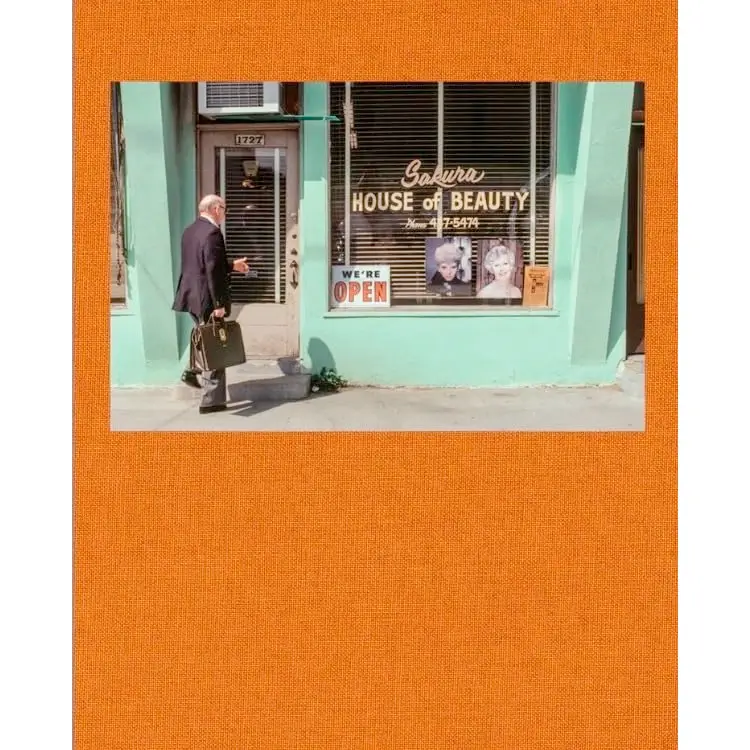

House of Beauty © Janet Delaney

First I want to say how amazing it was to collaborate with Clint and Alex Woodside, owners of Deadbeat Club Press. They were fully committed to making the best possible product and included me in all of the decisions along the way.

For over thirty years these photographs had been sequenced for a slideshow. I understood that the sequence in the book would be different than the one I knew by heart. Turning pages is very different from watching images dissolve into one another. I took a deep breath and trusted that Clint would make it work. He completely changed the order of the images but he kept all of the text as it was. New eyes on a project can be so important. I suggested the cover photo and the orange color which surprised even me, but it was in keeping with the color scheme of the 1970s. Superimposing the photos of my dad in his car over the ads was a joint decision. Using the bold blue for Dad’s interview text was Clint’s brilliant answer to a problem I pointed out.

The book includes essays by both you and your mother Connie. Can you tell us more about how that familial dialogue shaped the narrative of the publication?

When I first formatted the slideshow into a book I wanted to highlight the stark difference between my dad's orphaned childhood and the family life he created. I had not included the interview I did with my mom into the slideshow because her tone was so different; she is much more formal. When I revisited it for this version of the project I saw that her personal experience as both the wife of a salesman and as someone who worked in the salons would deepen the storyline.

The open spine and compact format give the monograph a raw, tactile presence. Was that a deliberate reflection of the working-class themes within?

I like your idea that it was based on the working class themes within, but I don’t know that that was the direct intention. I love the functional appearance of the spine but most importantly I love that it allows the book to lay flat which I think is essential for double page spreads. Having images change size from full bleed to half page affects the pacing or rhythm of the story. The compact size works well for a book with a fair amount of text.

Themes of labor, cities, and public/private life run throughout your entire body of work—from South of Market to Red Eye to New York and now this. What continues to draw you to the documentation of people at work and the places they inhabit?

Where we live and work shapes a huge part of our lives. I am always looking closely at the economy and its impact on the social/political culture of our time. I grew up in a small town environment in the shadow of a big city. Early on I had considered a career as an urban planner. So my obsession with a sense of place has deep roots. And finding work as an artist has always been a challenge. Where we live and how we support ourselves is determines much (but not all) of who we are. I think this perspective is important to foreground.

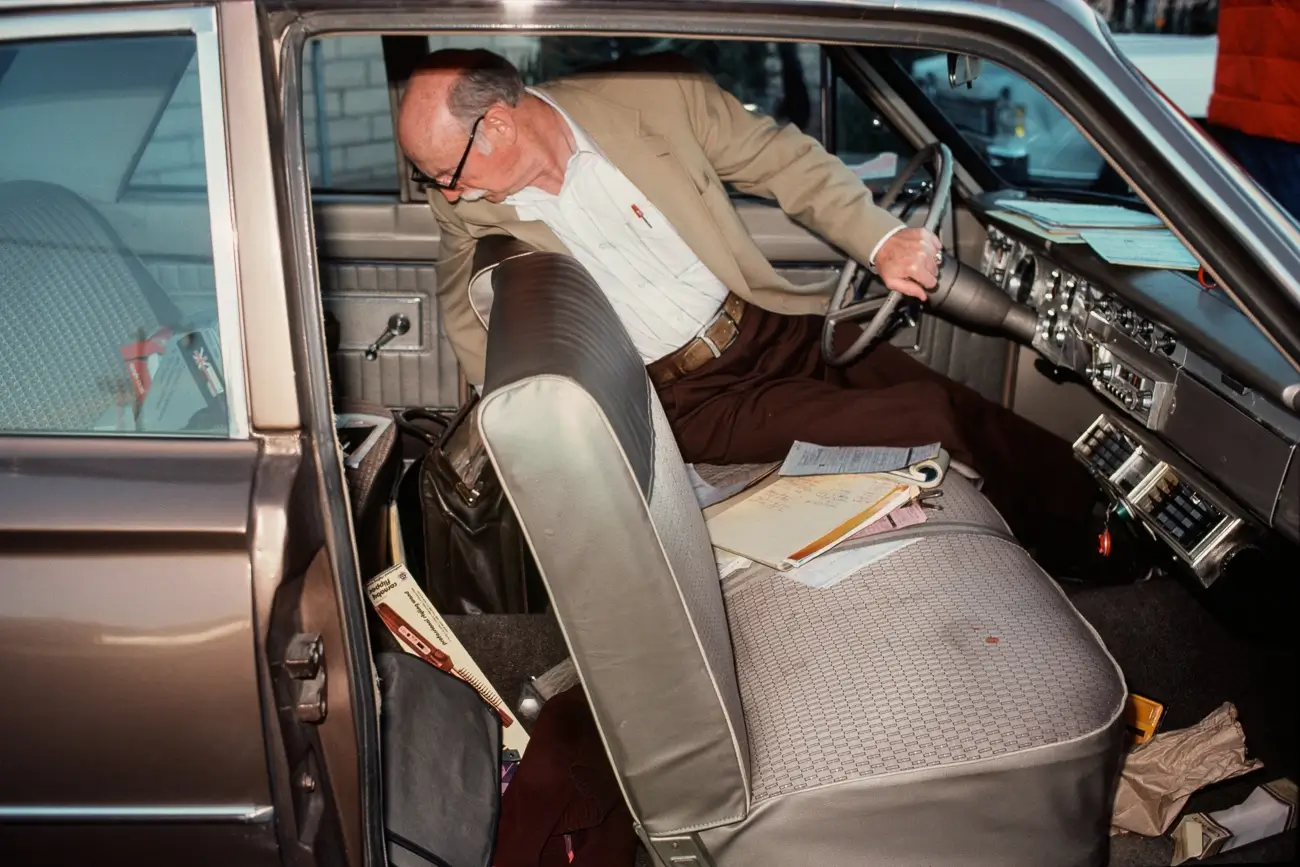

Car as Office © Janet Delaney

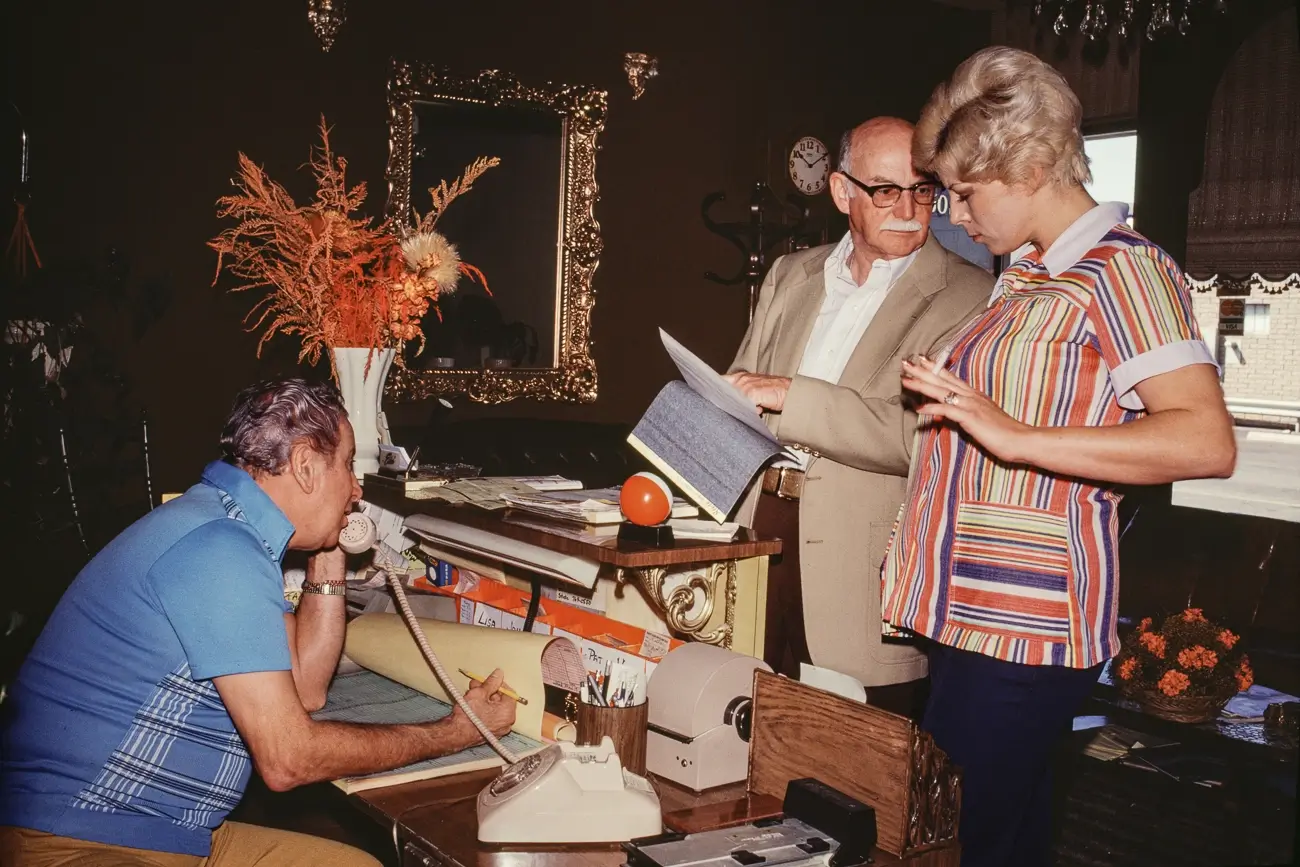

Checking Price List © Janet Delaney

As soon as I could drive, at 16, I would go to downtown Los Angeles to see the latest art films. Even though they were often way over my head, I thought filmmaking would be my calling. But eventually I realized how independent I could be with still photography. So when I first discovered the magic of a two projector slideshow with sound I was immediately sure that this would be a good way to produce my work. Low budget and independent

I continue to organize my projects around specific themes, using a combination of research, interviews and personal experience to create a narrative structure. In still photography, images can be seen and seen again with a new understanding. This double vision is some that the book format exploits so well. I work from the literal to the poetic in order to allow the reader room to breathe.

Your current Guggenheim project explores tech workers—arguably the polar opposite of your father's world. What parallels, if any, do you see between these different work environments?

Just like my dad, tech workers work all the time! The offices I visited were tricked out to look a bit like adult playgrounds with colorful furniture, 5 star cafeterias and heated toilet seats. There were perks like dry cleaning pick ups. All this conspired to keep people at the “office” 24/7. Also for some, the idea of being independent, not salaried, doing gig work, felt very similar since my dad worked on commission for over 30 years. If he wasn’t out selling, he wasn’t making any money. Now many in tech have moved to working from home which has benefits and challenges on both a personal and larger social level.

The title Too Many Products, Too Much Pressure feels like both a literal description and a metaphor. What does it mean to you now?

As a consumer society we are awash in choices that can overwhelm us. And now with the ease of online shopping and instant delivery we can fulfill any perceived need. The way money slips out of our phones is particularly unnerving, even seductive. It is as if we have a free pass, till the credit card bill arrives. So we are living in a world of too many products which is creating too much pressure!

What do you hope readers or viewers take away from this story—not just about your father, but about work, love, and the often-unseen emotional costs of providing?

Your questions have encouraged me to dig into layers of meaning that have helped me have a better understanding of this work. The fact that it has been well received forty years after it was originally made shows me that I touched on some important universal themes. One middle-aged man said to me after seeing the book and the slideshow, “I need to go home and talk to my father right now!” That would be the best outcome - that the book encourages people to engage more deeply with one another, we all have important stories to share.

Anything else you would like to add?

No, Thanks again for your questions.

Counting Money © Janet Delaney

Counting Money © Janet Delaney

Janet Delaney’s current photographic work uses a fine art approach to explore the social and political dynamics of city life. Her books include

South of Market (MACK 2013), which documents the gentrification of a working-class neighborhood.

Public Matters, (MACK 2018) addresses public life in Reagan era San Francisco and

Red Eye to New York, (MACK 2021) finds public and private worlds on the stage of 1980s Manhattan. She is currently working on a sequel to South of Market, examining the impact of the arrival of new technology companies on her old neighborhood.

Delaney’s awards include a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2020 and three National Endowment for the Arts Grants. Her photographs are in the collections of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the de Young Museum and the High Museum, Atlanta among others. She has shown in museums and galleries locally and internationally.

Janet Delaney received her MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute and held a faculty position at the University of California, Berkeley. She lives and works in Berkeley, California.

www.janetdelaney.com

@janet_delaney

All About Janet Delaney