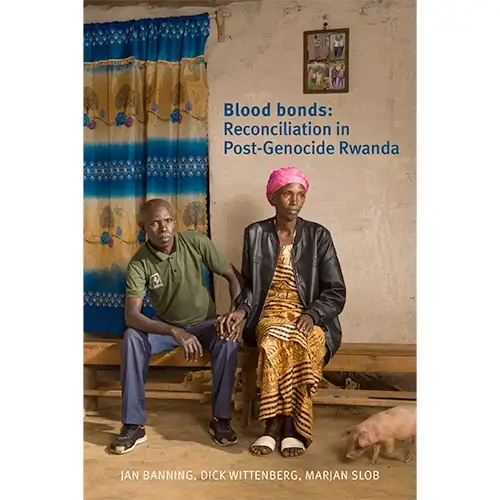

Blood Bonds: Reconciliation in Post-Genocide Rwanda is a new photobook by photographer

Jan Banning and journalist Dick Wittenberg, with an essay on forgiveness by philosopher Marjan Slob. It addresses the genocide in Rwanda, the reconciliation programs that followed, and presents 18 joint portraits of survivors and perpetrators.

The photographs show unlikely pairs of former enemies: a survivor of violence and the perpetrator who harmed them or their family. They live in the same villages, share daily life, and in some cases describe each other as friends or even family. “We live on the same hill. I hear her when she calls me,” says Alphonse, who murdered Liberatha’s brother, but now helps care for her.

The photographs are unflinching yet respectful. In one portrait, a man and woman sit on a rough wooden bench in a sparsely furnished home, pigs wandering in the foreground. The scene is plain, but Banning’s controlled light accentuates their faces and their clasped hands, giving the moment a solemn gravity. In another, two men sit closely on a patterned chair, their bodies tense but joined in the frame, the light drawing out the texture of skin, fabric, and wall. Two photographs bring together judges and the men they convicted.

Celestin Kayijuka (70) and Jean Marie Mukyenrwari (62) © Jan Banning

Celestin (left) lost four children and seventeen other relatives, including his father and two sisters, who were murdered by fellow villagers during the genocide. He bears many scars and walks with a limp from a brutal attack during his flight. Jean Marie murdered Celestin’s father, served ten years in prison, and made a confession during a gacaca trial. Later he personally apologized to Celestin and his brothers, which led to reconciliation. “At parties, we now dance together,” says Celestin

The 1994 genocide in Rwanda was one of the most intimate and large-scale acts of violence of the 20th century. In just 100 days between 800,000 and one million people were killed, mainly Tutsis but also Hutus. Perpetrators were neighbors, teachers, church leaders, even family members, who attacked face-to-face with machetes, clubs, and spears. The book not only recalls these events but also places them in the longer history of tensions between Hutus and Tutsis, colonial manipulation, ethnic propaganda, and civil war.

After the genocide, survivors, perpetrators, and bystanders had to live together again. The Rwandan state pursued justice through the gacaca (pronounced: katschatscha): more than 12,000 village courts tried over one million suspects. The aim was to punish crimes, reveal truths to help restore communities. But trials also reopened fear and resentment, leaving many with scars that law alone could not heal.

Alongside gacaca, community-based sociotherapy was developed, known as Mvura Nkuvure – “I heal you, you heal me.” In weekly group sessions, survivors and perpetrators sing, talk, and share stories, gradually building trust. Since 2005, more than 115,000 people have taken part in Rwanda. The method has since been applied in Liberia, Congo, Uganda, Ethiopia, and South Sudan.

Marianna Nyirantagorama (58) and Marc Nyandekwe (60) © Jan Banning

Marianna and two sisters were the only ones in their family who survived the massacre in the local church. They had hidden among the corpses. But one of the sisters was handed over to a mob of killers by their neighbor Marc. She and the remaining sister later escaped to Bisesero, where a large group of Tutsis resisted. Most of them perished after being abandoned by French peacekeepers. After being convicted in a gacaca court, Marc spent nearly seven years in prison. Once released, he hid for years out of shame and fear—until he encountered Marianna in a sociotherapy group, and she reached out her hand to him.

The book also opens a philosophical dimension. In her essay The Mystery of Forgiveness, Marjan Slob distinguishes reconciliation from forgiveness, calling forgiveness “the inner act through which a victim renounces the impulse to revenge,” yet admits that “neither reconciliation nor forgiveness can really be seen,” because they unfold in an inner world that others cannot access. She asks what outsiders can truly know, whether some reconciliations are genuine or a “pact of convenience,” and explores the role of society to uphold the moral ground that makes forgiveness possible – where the state can punish, but only the victim can forgive.

Photography is at the core of the project. Jan Banning’s portraits are grounded in social focus, continuing a practice established in Bureaucratics, Comfort Women, and Law & Order, where rigorous research underpins formal, deliberate composition. His photographs have the quality of Dutch Golden Age paintings: the measured lighting, the balanced arrangements, and the directness of the gaze elevate the subjects into figures of historical record. Banning does not aestheticize pain, nor does he reduce his sitters to symbols. He places survivors and perpetrators together in the same formal space to confront the ambiguity, prompting the viewer to ask who is victim, who is perpetrator, and what trust looks like. The restraint of his style – the stillness, the absence of gesture – keeps attention and leaves room for complexity.

Blood Bonds stands as testimony to the fragile but vital process of reconciliation after atrocity. It shows how people once bound by violence find ways to live together again. Its relevance extends beyond Rwanda, offering perspective for today’s other conflicts. “Even after a genocide, there is life. Even after a genocide, there is hope.”

Ancile Unabagira (57) and Ancile Nyiramimani (52) © Jan Banning

Ancile (right) lost her husband, parents, and two siblings during the genocide. She fled with her three young children, surviving with help from kind Hutus. Ancile Nyiramimani, who betrayed four relatives of Unabagira's husband, later joined the same CBS Rwanda socio-therapy group. There, Unabagira learned of Nyiramimani's extreme poverty, including having barely any clothes and only banana leaves as a mattress. Moved by her story, the two embraced, finding reconciliation.

is an artist-photographer. He achieved worldwide renown with his book and exhibition Bureaucratics (2008), about bureaucrats in eight countries on five continents. This work was exhibited in more than twenty countries. His projects, some of which have taken shape over many years, always have a social and political focus and strive to contribute to the public debate. He has won many international awards, including a World Press Photo Award in 2004 and eleven Silver Camera awards. His work is included in museum, corporate and private collections in various countries and has been published around the world.

Dick Wittenberg

Dick Wittenberg is a journalist and author. He has worked for Dutch newspaper NRC for over thirty years, including as a sports journalist, United Kingdom correspondent and Africa editor. His journalism has won many awards. Together with Jan Banning, in 2008 he won the Bob den Uyl Prize for their (first) book on everyday poverty in a village in Malawi. He has also written books about barbed wire and about the legacy of a last parent.

Marjan Slob

Marjan Slob is a writer and philosopher. She was Denker der Nederlanden (‘Thinker of the Netherlands’) from 2023 to 2025, an honorary title which allowed her to express the beauty and importance of philosophy to the broadest possible public, as well as through a range of media. She writes essays for various magazines and newspapers and for many years wrote a column in Dutch daily de Volkskrant. She has written several books, including Hersenbeest (‘Brain Beast’, winner of the Socratesbeker award) and De lege hemel (‘The Empty Heavens’, J. Gresshoff prize for non-fiction).

Liberatha Nyirasangewe (70) and Alphonse Kanyemera (78) © Jan Banning

Liberatha lost five children, including baby twins who were murdered at the start of the genocide. Her entire extended family and many friends were also killed. After the genocide she was, in her own words, “insane” for years and consumed by rage. In a sociotherapy group, she met Alphonse, who had served fifteen years in prison. He had murdered her brother. He offered his apologies and asked for forgiveness. Now they care for each other.