In 2025, World Press Photo marks its 70 year anniversary; a milestone which provides the opportunity not only to look back at the remarkable history of the organization, but also to examine how the images World Press Photo awarded and helped to give a global platform over the past seven decades have shaped the public’s understanding of the world.

To mark the occasion of this anniversary, and as part of a series of special events across 2025, a major exhibition, What Have We Done? Unpacking Seven Decades of World Press Photo, curated by artist and photographer

Cristina de Middel, will take place in several locations. The world premiere of the exhibition will take place on 19 September 2025 at the Niemeyerfabriek in Groningen, and is hosted by

Noorderlicht—one of the Netherlands’ leading platforms for photography and lens-based media. The show will run until 19 October, with a press preview scheduled for 18 September. It will also be shown in Johannesburg, South Africa, at The Market Photo Workshop from 20 September and in Dhaka, Bangladesh, at Drik Picture Library from 21 November 2025.

© Georges Mérillon, France, Gamma

28 January, 1990

Nogovac, Kosovo, Yugoslavia Family and neighbors mourn the death of Nasimi Elshani, who was killed during a protest against the Yugoslavian government's decision to abolish the autonomy of Kosovo. His mother Sabrié and sister Aferdita are sitting on the right, and his sister Ryvije in the middle. Since 1974, Kosovo had been an autonomous province within Serbia and Yugoslavia. In 1989, Slobodan Milosevic, the Serbian leader, reduced Kosovo’s autonomous status and started a policy of cultural oppression of the ethnic Albanian population. At the end of January 1990, unarmed ethnic Albanians in Kosovo clashed with Serbian armed troops. Serb police reinforcements were sent to the province to aid federal troops already stationed in Kosovo. The episode would form an overture to the Kosovo War of 1998-1999.

Reflecting on the 70th anniversary has brought World Press Photo back to its extensive archive spanning seven decades of stories that have been powerful vehicles of change. They’ve helped raise awareness of critical global issues and to shed light on little-known but important stories. Still, delving deeper into the archive, World Press Photo has also had to confront the unintended consequences of their choices, whether from assumptions made, to stereotypes that may have been perpetuated, or voices that were underrepresented. This exhibition is an invitation to reflect on the various recurring visual patterns that are to be found in different eras and to start a dialogue.

The exhibition features over 100 photographs from those working across the 70 year period – from Horst Faas, Don McCullin, David Chancellor, Eddie Adams, and Steve McCurry, to Johanna Maria Fritz and Sara Naomi Lewkowicz. This exhibition is an invitation to rethink not just how visual language has evolved but how we, as viewers and citizens, should learn to read images with a sharper and more critical eye. This tension between new tools and old habits raises a crucial question: If the ways we capture and share images have changed, why do we continue to tell the same stories in the same way? What do these recurring images say about what we choose to see—and what we ignore?

The exhibition is organized around six recurring visual patterns identified in World Press Photo’s extensive archive:

Weeping Women and Men Rescuing

The stories told in the archive often follow a pattern: women weep, men rescue. These repeated images aren't random – they reinforce traditional ideas about who's vulnerable and who's strong. We see tear-streaked female faces, frozen in grief, while men are captured mid-action, carrying the wounded, giving orders, pulling others from danger. Without saying a word, these pictures shape how we think about gender roles during disasters, conflicts, and tragedies.

© Johanna Maria Fritz, Germany, Ostkreuz, for Die Zeit

09 June, 2023

A volunteer rescues cats in the flooded harbor district in Kherson, Ukraine. Flooding from the breached Kakhovka Dam lasted for 19 days.

On 6 June 2023, explosions damaged the wall of the Russian-controlled Kakhovka Dam in southeastern Ukraine, causing extensive floods in Kherson, downstream on the Dnipro River. Kherson, a strategically important city in the Russia-Ukraine war, had been one of the first to be occupied by the Russians in March 2022. In November that year, Ukraine retook the city, which is on the west bank of the river, forcing Russian withdrawal to the east bank.

The cause of the explosions is disputed, with both Russia and Ukraine accusing each other of blowing up the dam. Other sources cited neglect of the dam’s maintenance and infrastructure, or mines that had washed free of riverbanks as causes. After the initial breach of the dam, the force of the water flowing out damaged it further.

The breach in the dam flooded at least 17,500 homes on both the Ukrainian west bank and the Russian-held east bank of the river, according to a Kyiv School of Economics report. An AP investigation in December 2023 put the death toll in the hundreds. Flooding lasted 19 days, and rescue and recovery efforts were hampered by Kherson’s proximity to the frontline, as the city suffered ongoing shelling.

The Kherson flood highlights the issue of the weaponization of the environment and natural resources. Russian forces have used deliberate flooding to slow down the Ukrainian counteroffensive in the past, either by breaking existing dams or building new ones, according to Bellingcat and the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. Ukraine admits using similar tactics at the start of the war. Ukraine subsequently investigated the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam and began building an ecocide case against Russia for the Internationa

Press coverage of war often follows a familiar script, shaping perception rather than revealing full reality. White soldiers, predominantly, appear in the archive in moments of exhaustion or contemplation – images that humanize them while leaving their actions on the battlefield unseen. Soldiers with darker skin are more frequently shown in combat, reinforcing narratives of aggression and dehumanization. These choices create an imbalance in documentation, influencing who appears as a victim and who is framed as a threat.

At the same time, destruction is often aestheticized. War debris transforms into striking compositions, distancing viewers from the human toll of violence. This visual approach echoes Hollywood's cinematic language, where conflict is dramatized and romanticized, making it easier to digest.

By emphasizing soldiers' emotional burdens while abstracting the consequences of their actions, these images shape a narrative that simplifies war, making it familiar rather than unsettling.

© Mustafa Hassouna, Palestine, Anadolu Images

19 October, 2023

A resident of al-Zahra walks through the rubble of homes destroyed in Israeli airstrikes. The strikes hit around 25 apartment blocks in the university and residential neighborhood. At the time of writing (4 March 2024), Israel’s attacks on the occupied Palestinian territories during the Israel-Hamas war had killed some 30,000 people and injured more than 70,000. Gaza City, Gaza.

This year, the jury made the exceptional decision to include two special mentions in the 2024 World Press Photo Contest selection:

“These two special mentions reflect the gravity of the Israel-Hamas war in 2023, the extreme suffering of civilians, and its global political impact. While each photograph shows a single individual in the aftermath of a horrific attack, the contrast between the scenes helps viewers understand the differing scales of devastation without minimizing the individual suffering. We also wish to pay tribute to photographers reporting on this war, who are subjected to huge amounts of trauma, risk, and personal loss, particularly in Gaza.”

© Wojciech Grzedzinski, Poland, Napo Images for Dziennik

13 August, 2008

A Russian soldier lights a cigarette just outside Gori. Conflict broke out between Russia and Georgia in August over the breakaway region of South Ossetia. On August 7, Georgia launched an attack on South Ossetia, saying its aim was to restore constitutional order. Russia sent troops in support of the separatists, and on August 9 staged an air attack on Gori, a Georgian town near South Ossetia. Russian troops occupied the area around Gori, but later pulled back under a ceasefire.

Media representations create distinct visual worlds for men and women. Men consistently appear as figures of action and authority – triumphant athletes, determined leaders, protective forces during crises. These images celebrate physical strength, decisive movement, and professional achievement.

Women, by contrast, occupy more limited visual roles. They appear as decorative elements, emotional responders, caregivers, or objects of desire. Even when portraying professional women, visual framing often emphasizes appearance over competence. In tragedy, women become symbols of suffering rather than agents of change.

These visual patterns reflect deeply embedded storytelling traditions. Repeated across decades of news imagery, they normalize specific gender expectations – reinforcing who acts and who reacts, who shapes events, and who experiences them. These contrasting visual languages don't merely reflect society but actively shape our understanding of who belongs in which spaces and roles.

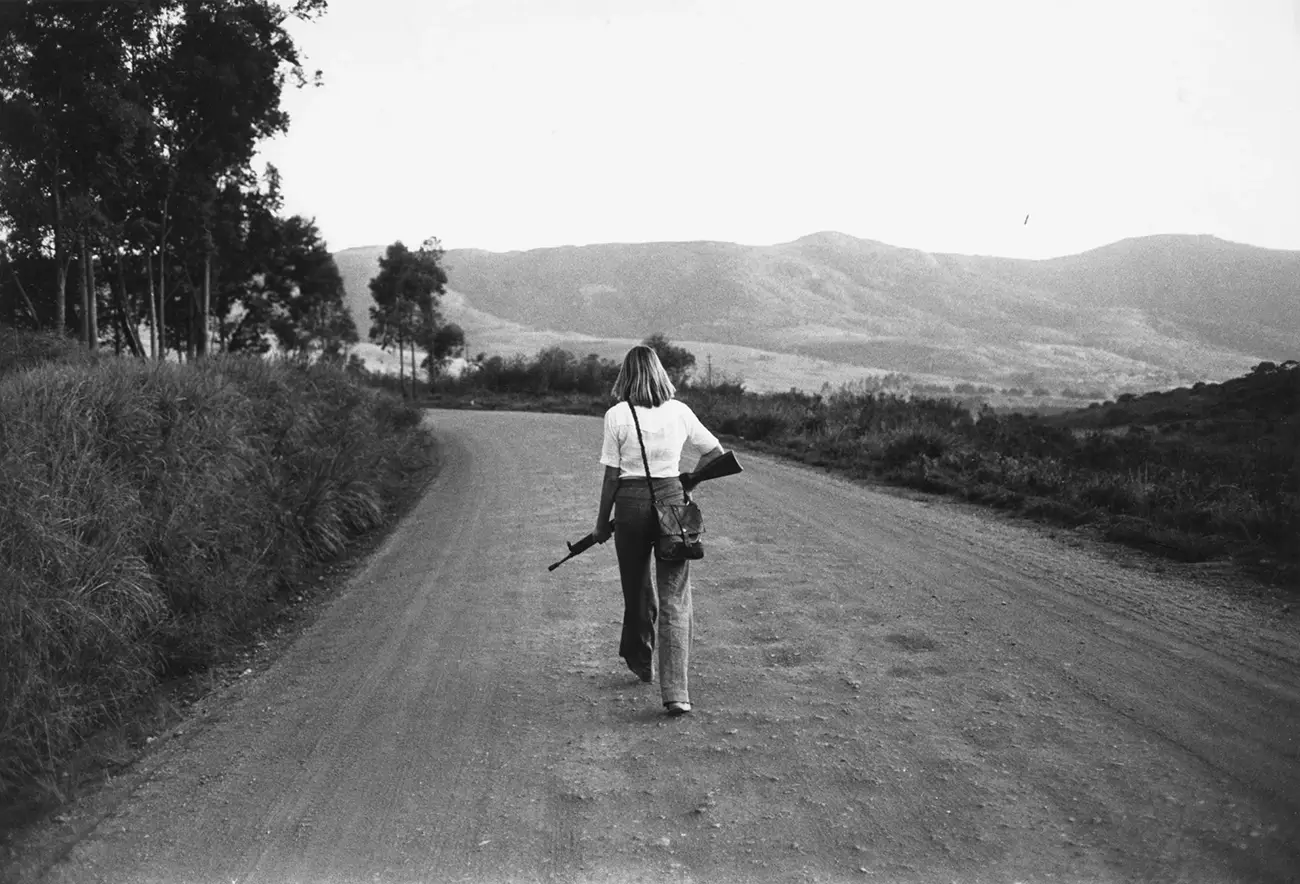

© Eddie Adams, USA, Associated Press

01 January, 1978

White life in Rhodesia:. A school teacher walks home after her car broke down. On 3 March 1978, after 14 years of civil war, Rhodesian Prime Minister Ian Smith and bishop Abel Muzorewa of the United African National Council signed an agreement, which became known as the Internal Settlement. In 1965 Smith, prime minister of the British colony since 1964, had declared Rhodesia unilaterally independent under white minority rule. The declaration not only sparked international outrage and economic sanctions, but also a guerrilla war against white rule by different political and military factions. By signing the Internal Settlement and organizing new democratic elections, it was expected that all sanctions would be lifted. However, the settlement was condemned by the United Nations' Security Council, and as not all significant parties had been involved in the process, the civil war continued. The war would not end before December 1979, when in Lancaster House, London, all parties came to a peace agreement and a new constitution, guaranteeing minor rights..

Western media and culture has long framed Africa as an exotic and unknowable place – a dark continent rather than a Black one. This perspective is reinforced through recurring visuals: leaders portrayed in ways that undermine their authority, an overwhelming focus on war, famine, and suffering, and a scarcity of stories that build respect, nuance, or confidence in a continent far more complex than these narratives suggest.

Equally persistent in the World Press Photo archive is a fascination with Black skin itself. Close-ups linger on its texture as if observing something unfamiliar, echoing colonial-era representations where African bodies were treated as specimens rather than individuals. This aesthetic curiosity, combined with a limited and repetitive visual language, continues to shape how Africa and its people are perceived, reducing a vast and diverse reality to a narrow and distorted frame.

© William Daniels, France, Panos Pictures for Time

09 December, 2013

In March, an alliance of mainly Muslim rebel groups known as Séléka seized power in the Central African Republic (CAR). Hundreds were killed, and some 400,000 people displaced, as violence in the CAR escalated.

Photographers are trained to see what others miss — a fleeting silhouette, a momentary shadow, a perfect collision of form and light. Whether capturing the ecstasy of a goal or the chaos of a war zone, their skill lies in freezing time at its most expressive. This pursuit of the decisive moment — that impossibly balanced instant — is what gives photography its power, and its pleasure. But the same tools that elevate one kind of story can complicate another.

The use of beauty — of carefully composed frames, cast shadows, dramatic contrasts, and aesthetic precision — in images of conflict or suffering raises difficult questions. When does visual impact deepen our understanding, and when does it risk turning pain into spectacle? In these contexts, beauty can create distance, rendering horror strangely palatable, even poetic. It can help make sense of chaos — or obscure the truth of it.

© John Stanmeyer, USA, VII for National Geographic

26 February, 2013

African migrants on the shore of Djibouti City at night raise their phones in an attempt to catch an inexpensive signal from neighboring Somalia—a tenuous link to relatives abroad.

Djibouti, at the narrow southern entrance to the Red Sea, has become a gateway for migrants from the Horn of Africa heading to the Gulf States and beyond. This photo was taken as part of a project to ‘walk the world’ following the ancient paths of human migration, from Africa to Tierra del Fuego at the tip of South America. When the image became World Press Photo of the Year it sparked surprise because it was different from previous winners, which often show conflict or historic moments. Instead, it is nuanced, poetic yet instilled with meaning. Kim Hubbard who commissioned the story for National Geographic said: “John managed to distill our entire story into one beautiful, moonlit image: modern day migration meets the universal desire for connection.”

Fire and smoke have long been symbols of chaos and transformation – whether in ancient myths, biblical visions of hell, or the burning cities of history. In photojournalism, they serve as unmistakable markers of crisis, turning moments of conflict and disaster into powerful, almost elemental imagery. A cloud of smoke on the horizon signals destruction before we even know the details.

But fire doesn't just document events – it shapes how we remember them. Its presence in an image adds weight, a sense of urgency, and sometimes even a kind of tragic beauty. As these visuals repeat over time, they become part of an established language of drama, reinforcing how we picture upheaval and loss.

© Steve McCurry, USA, Magnum Photos for National Geographic

01 March, 1991

Camels search for untainted shrubs and water in the burning oil fields of southern Kuwait. As his army retreated from Kuwait, at the end of the First Gulf War, Saddam Hussein ordered the ignition of the oil fields that scatter the country. The effect was an ecological disaster of unimaginable scale. Steve McCurry: 'Photographing the ecological disaster in the aftermath of the Gulf War was one of the most amazing experiences of my professional life. All of Kuwait seemed like an end-of-the-world scenario from a Hollywood production. Over 600 oil wells were on fire, turning daytime into night. The smoke was so thick that sometimes you couldn’t breathe. Animals were left to wander among the burning oil fields, looking for food and water. I followed this family of camels for about an hour in my jeep, getting out from time to time to make photographs. I guess my motivation was to show the world this tragic, needless catastrophe.' (World Press Photo retrospective Children's Jury exhibition, 2003)

, said,

''his exhibition is inspiring, critical, mind-opening, reflective, and hopeful. It offers a fresh take not only on the World Press Photo archive but also marks the first time we invite an external curator to explore our history in this way. We recognize that this exhibition presents just one perspective. Just as people interpret the same image in different ways, archives too can be viewed through many lenses. By examining recurring visual patterns, our aim is to create a space for collective reflection and open dialogue. In choosing to open up our archive in this manner, we also choose to be vulnerable. We do so with the conviction that acknowledging our past—its strengths and its flaws—is essential if we are to learn, evolve, and do better. By understanding where we’ve been, we can more thoughtfully navigate where we’re going.''

Roosje Klap, General and Artistic Director, Noorderlicht: ''Our collaboration with World Press Photo on ‘What Have We Done?’ feels fitting and necessary, especially here in Groningen! Noorderlicht has grown in this city since the end of the 80s, because it offers space for critical thinking, collectivity, and imagination. It is these images that have shaped our world and our understanding of one another. Alongside this, we’re presenting ‘Rauw Vermogen’, our exploration of the important themes of our time through the eyes of seven young Dutch photographers from the North. Together in the Niemeyerfactory, these exhibitions offer us the chance to reimagine how we engage with the world around us.''

Running alongside What Have We Done? are pop-up festivals in each location which will bring together critical thinkers, photographers, and speakers for a dynamic program of talks, presentations, workshops, guided tours, and educational activities – all aimed at deepening engagement with the exhibition’s themes and sparking meaningful dialogue. The complete programs will be shared soon.

In the same location as What Have We Done? at the Niemeyerfabriek, in Groningen, the Netherlands, the exhibition Rauw Vermogen will also be presented: A new commission project by Noorderlicht, developed with seven emerging local photographers who are looking at the region’s future through the lens of its people, landscape, and labor. The venue is open to see both shows Tuesday to Saturday, 10-5 pm and Sundays 12-5pm. Closed on Monday.

© Francesco Zizola, Italy Contrasto for Max

01 January, 2001

Nuba boy of the Tira tribe. In the mountains of central Sudan, the Nuba people struggle to preserve a culture under threat. The Nuba have lived in the inaccessible and remote region for hundreds of years. However, their numbers are dwindling, as fierce fighting between government troops and the Sudan People's Liberation Army forces thousands to flee, moving to urban centers for food and shelter. Displaced, or forced to hide in caves, they also face hostility from the fundamentalist Muslim government who has declared Nuba Mountai

After 10 years as a photojournalist,

Cristina De Middel shifted her practice to a more conceptual approach in order to question the documentary value of photography. In 2012, she produced the acclaimed series The Afronauts, triggering a decade of work around the role of photography in creating stereotypes. Besides her prolific career as an author, and as an active member of the

photography community, Cristina has been invited to curate festivals like Lagos Photo, PhotoEspaña, and San José Photo in Uruguay. She has published more than 14 photobooks and her work is constantly on show in different institutions and venues. Cristina is also on the board of Vist Projects, a platform to support Latin American visual storytelling, and she is a member of Magnum Photos agency and its recent president.

About Joumana El Zein Khoury

Joumana El Zein Khoury is the executive director of the World Press Photo Foundation.

She has over 20 years of experience in international cultural exchange, developing programs and fostering new talent. She was previously the director of the Prince Claus Fund, an internationally renowned institution supporting culture under pressure, where she was crucial to strengthening fundraising capabilities. Joumana was the director of Lutfia Rabbani Foundation for Euro-Arab exchange, for which she now continues her involvement as a board member. She has also worked with organizations including the Arab Image Foundation and the Baalbeck Festival. She is a member of the supervisory board of Manifesta, and the chair of the advisory board of the Ammodo Architecture Award.

About Noorderlicht

Noorderlicht is a platform for photography and lens-based media in Groningen and organizer of, among other things, the Noorderlicht Biennale. Noorderlicht has been showcasing images in a rapidly changing world since 1980. With exhibitions, research, and educational programmes at the intersection of art and society, the platform seeks out new stories for our time. Roosje Klap has been the general and artistic director of Noorderlicht since May 2024. She brings over two decades of experience at the intersection of visual culture, education, and technology. She serves on several boards, including the Gerrit Rietveld Academie and Oude Kerk Amsterdam, and received the Gouden Kalf award for Best Digital Cultural Production in 2022. Under her leadership, Noorderlicht launched its 30th biennale Machine Entanglements, with a global preview at the 2025 World Expo in Osaka, Japan.

About the World Press Photo Foundation

World Press Photo is an independent non-profit organization that champions the power of photojournalism and documentary photography to deepen understanding, promote dialogue, and inspire action.

Founded in the Netherlands in 1955, our annual and thematic exhibitions reach millions of people in over 80 locations worldwide each year, and our online work reaches millions more. We create space for reflection in times of urgency, while upholding standards of accuracy, authenticity, visual excellence, and diverse perspectives. Our education programs help photographers reach these standards, and members of the public recognize them.

We are thankful for the support of our funders, particularly our strategic partners the Dutch Postcode Lottery, PwC, and FUJIFILM Corporation.

The What Have We Done? exhibition is supported by

The Open Society Foundation.