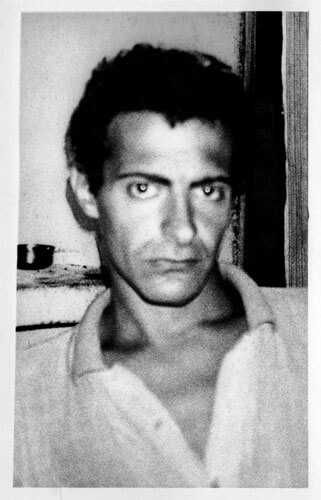

Born in Marseilles, Antoine d'Agata left France in 1983 and remained overseas for the next ten years. Finding himself in New York in 1990, he pursued an interest in photography by taking courses at the International Center of Photography, where his teachers included Larry Clark and Nan Goldin.

During his time in New York , in 1991-92, D'Agata worked as an intern in the editorial department of Magnum, but despite his experiences and training in the US, after his return to France in 1993 he took a four-year break from photography. His first books of photographs, De Mala Muerte and Mala Noche, were published in 1998, and the following year Galerie Vu began distributing his work. In 2001 he published Hometown, and won the Niépce Prize for young photographers. He continued to publish regularly: Vortex and Insomnia appeared in 2003, accompanying his exhibition 1001 Nuits, which opened in Paris in September; Stigma was published in 2004, and Manifeste in 2005.

In 2004 D'Agata joined Magnum Photos and in the same year, shot his first short film, Le Ventre du Monde (The World's Belly); this experiment led to his long feature film Aka Ana, shot in 2006 in Tokyo.

Since 2005 Antoine d'Agata has had no settled place of residence but has worked around the world.

Source: Magnum Photos