My days at the Medium Festival of Photography reviewing portfolios were strangely bookended. The first day, I had back-to-back meetings with artists who were creating their images with fire and water (not cameras) and I thought, there's got to be an Air project soon, and there was. And Earth. All the elements in one place. There were also a lot of portfolios in between that investigated themes of family and the land and the plight of animals and humans as well as just some damn good street photography. (These will have to be discussed in a second article since attention spans are only so long).

For those of you who don't know what Medium is, the

Medium Festival of Photography began in 2011 when a group of photographers set out to create a unique experience for fine art photography in Southern California. Intent on developing an event where photographers could share ideas, make new connections and expand networks, it wasn't long before Medium was born and the community started talking. Now in their fourth year, the festival has gained an international reputation as a place to discover creative photography and intersect with emerging and established photographers, making San Diego an exceptional destination for photography.

Medium is run by a small team of committed individuals. Led by photographer

Scott B. Davis, with support from Anna-Leigh Zinza, Dana Mathews, and Alan Nakkash, they are committed to bringing an expressive and meaningful event to photographers from across the region and throughout the world. Their team of volunteers and behind-the-scenes muscle provides a crucial amount of fuel to make Medium everything it is today. The 2015 event not only contained two days of portfolio reviews which I was thrilled to be a part of, but the festival also featured a key note speaker, none other than

Jim Goldberg, an exhibition juried by Gordon Stettinius of Candela Books: Size Matters, and a series of lectures and talks relating to photography and current themes and matters relevant to contemporary emerging and established photographers.

Now back to the portfolio reviews where each artist has 20 minutes to show you their photographs and have a dialogue about them. It's a bit like speed dating, but also a great way to see a lot of work in a relatively short period of time. As a curator, I am always looking for new work and innovative ways of making it.

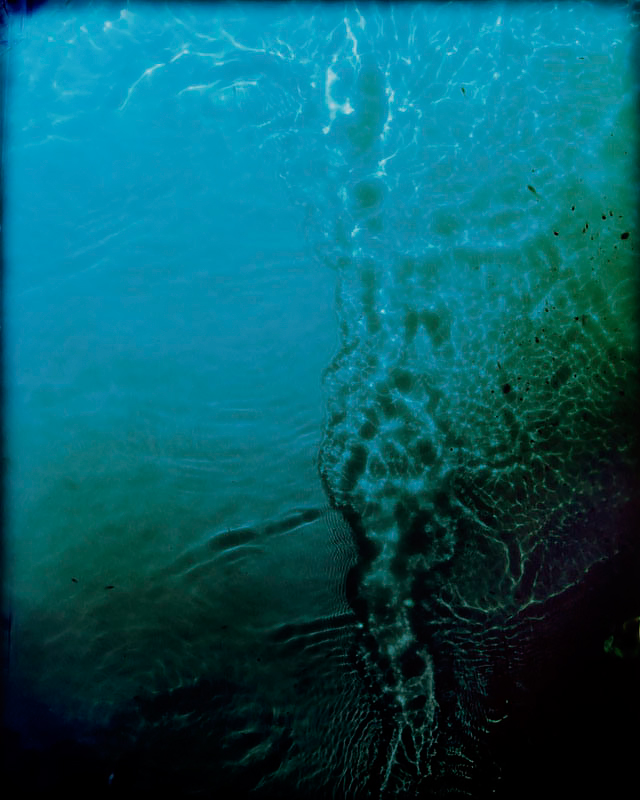

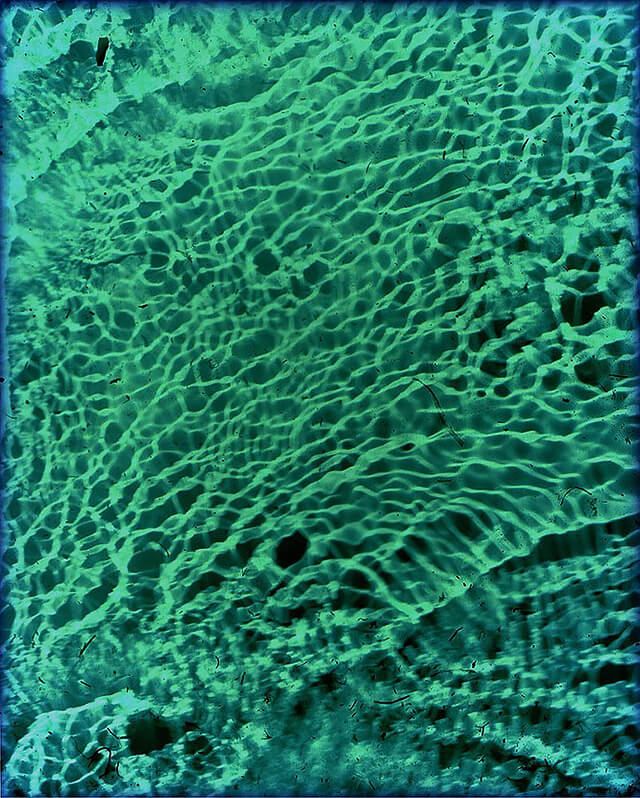

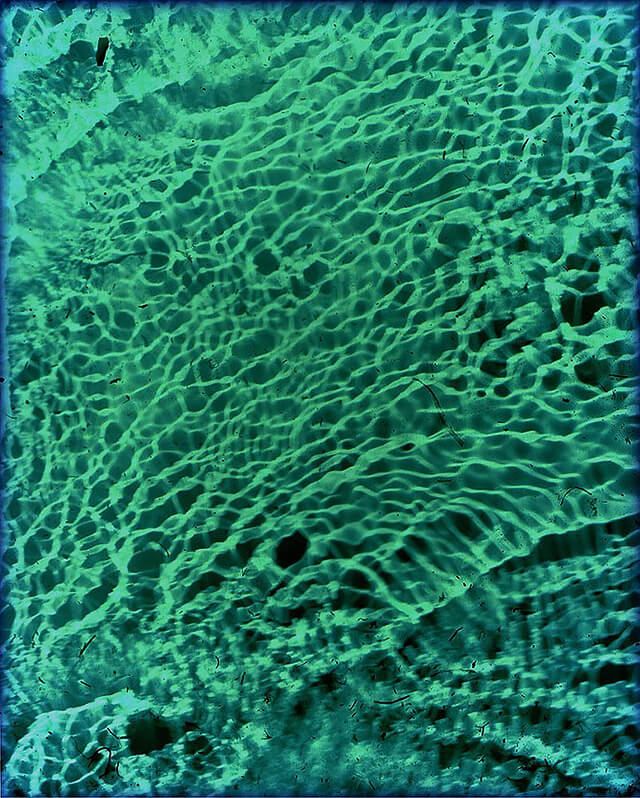

Kathleen Velo of Arizona has been working on a project called Water Flow. This is a visual comparison of water and water contents in the western United States. What's particularly compelling about these abstract images is the way Velo makes them. These brightly colored prints, ranging in tone from the deepest blue to pale green and blue-black, are photograms. They were created by submerging light sensitive chromogenic (color) paper underwater in the dark of night in various water sources and exposing the paper to the light of a strobe or the full moon. Water sources include natural ground water in remote creeks, streams, and arroyos, as well as the man made recharge basins of Colorado River water from Central Arizona Project canals. This project includes images made directly in the Colorado River as it flows from its headwaters in northern Colorado to the Colorado Delta in Mexico. The resulting photograms reveal the movement of the water across the surface of the paper, but also the unique print documents the contents of the water: salts, minerals, pollutants, other elements...each print a mystery and a message.

Immediately after Velo stood up from my table, another photogram artist sat down.

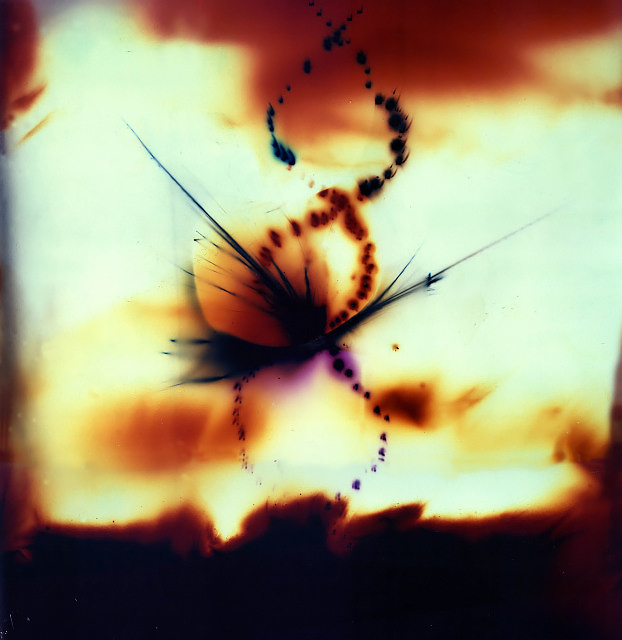

Ross Sonnenberg also had chromogenic prints, each unique, each vibrant, but his weren't fields of color. Instead they were explosions. Literally. For his latest body of work, The Big Bang, Sonnenberg put fireworks of varying types directly onto the photographic emulsion. The fireworks became not just the light source for the exposure, but also the subject itself. Following in the footsteps of artists like

Christopher Colville who makes exposures on gelatin silver paper with lit gunpowder and

Chris McCaw who lets the sun burn holes in his paper negatives turned positives, Sonnenberg experiments with fire. In his own words, the images, with all their beautiful imperfections, resembled images of the real solar system, created by the first Big Bang millions of years ago.

These two artists are definitely thinking outside the box when it comes to the creation of their images. Who needs a darkroom when you can take your traditional materials outside and expose them to the elements? I now sat down to wait for the next artist. It wasn't long before New Mexican artist

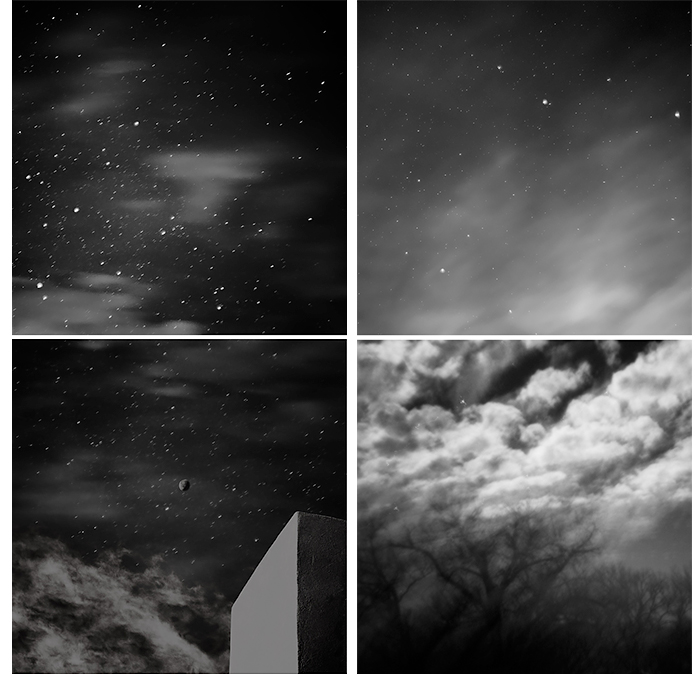

Michael Trupiano (an insomniac amongst other things) brought his work. He had a stack of diptychs of starry skies paired with night landscapes, some of them, well, most of them fairly eerie. What better to do at 3 a.m. when you're sleepless than to wander out into the unlit desert with your camera and photograph the clouds skittering across the night sky or the trees lit oddly by the moon? Sometimes the air in his pictures in tangible, thick with stars and planets. Sometimes it is a black void with 4 planes moving across its surface. Sometimes the moon looks more like a rock suspended in the air that you could pick up and throw away. I'm getting ideas for my own insomnia, though the brightness of my city lights wouldn't compare to the stillness of Trupiano's desert.

And lastly, there is someone I didn't sit across the table from, but someone who's work I've followed for a long time.

Jennifer Little has been photographing the earth and what we've done to it for years. Her devastating landscapes from Owens Lake and the Los Angeles aqueduct are evidence. This project, 100 Years of Dust, documents the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power's (LADWP) legally mandated dust mitigation program at Owens Dry Lake in Southern California. It is the latest chapter in a century of legal battles over water rights and air quality in Owens Valley. Owens Lake lies in Southern California's eastern Sierra, about 200 miles northeast of Los Angeles. This 110-square-mile lake began to dry up in 1913 when the City of Los Angeles diverted the Owens River into the Los Angeles Aqueduct. The new water supply allowed Los Angeles to continue its rapid growth and turned the arid San Fernando Valley into an agricultural oasis, but at a tremendous environmental cost. By 1926, Owens Lake was a dry alkali flat, and its dust became the largest source of carcinogenic particulate air pollution in North America(1). These pictures are beautiful while they document something tragic. The punished earth is almost too much to bear sometimes.

(Jennifer Little also recently had the misfortune of having all of her equipment, hard drives, and images stolen when her apartment was broken into... she has launched a crowd funding campaign to try to at least replace her gear, though her archive is irreplaceable. Jennifer has estimated that it will cost her $10,000US to replace all of this digital photography and audio/video equipment at once. She has never attempted to crowd fund the purchase of equipment before, but sadly, this is her only option other than taking on massive high-interest credit card debt. Any contribution you can make to help her replace her stolen camera equipment will be much appreciated.)

So in two days of reviewing portfolios, to find air, water, fire, and earth is a coup. And a revelation. These events are proving ground for many artists and the seeds of many exhibitions are planted here. My thanks to Scott B. Davis and his crew for giving me the opportunity to be exposed to these new works and new ideas. The next piece about the Medium Festival will spotlight other artists and themes noted during the portfolio reviews.

(1) William Fox, Camera Obscura: A photographic history of the LA Aqueduct, Boom: A Journal of California 3, no. 3 (Fall 2013): 43.